History > Catherine's Manifesto

Catherine's Manifesto - 1763

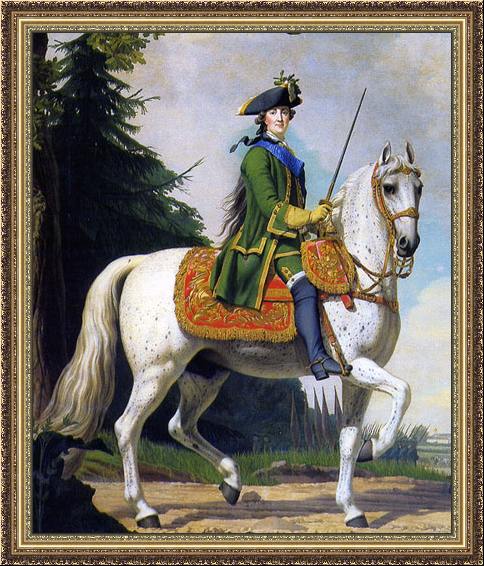

Catherine II of Russia (Catherine the Great) was born in Stettin, Pomerania, Prussia, as Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg. She was raised in an environment of German culture and traditions. Although born a princess, her family had little money, and an arrangement was made for her to marry Peter III, who stood in the line of succession to the Russian throne. She arrived in Russia in 1744 and married Peter in 1745. Catherine became Empress of Russia in July 1762 following a coup d'état and the assassination of her husband, Peter III, who had recently become Emperor following the death of his mother, Empress Elizabeth. Catherine's accession to power came at the end of the Seven Years' War, a religious and political struggle that left much of Western Europe in dire economic and social conditions.

Russia has a long history of recruiting Germans with the skills needed to develop the country.

For decades, Russia had attempted to productively colonize its empire to the south after winning territory from the Ottoman Empire. The government felt that the area along the lower Volga River was unstable, and bands of roving bandits made settlement impossible. Catherine and her government wanted to solidify this region as Russian territory, and she needed free settlers who would turn the land into productive farms and serve as a model for native people living in the area.

An attempt was made to lure colonists to the region in 1731, but fears about the lack of military protection resulted in almost no interest. In 1732, Empress Anna Ivanova resettled a group of over 1,000 Don Cossack families along the lower Volga under the pretext of protecting and stabilizing the frontier. The Cossacks reportedly made poor colonists and often took part in looting the trade routes in the region.

Attempts in the 1740s to attract Russian subjects to the lower Volga were problematic as serfdom prevented the free movement of the general population. The serfs were bound to the landowners who had no interest in releasing their workers or weakening the class system. Landowners were reluctant to create new farms in the troubled region. As a result, the Russian government began to look beyond its borders for colonists.

Empress Elisabeth resolved the question of inviting foreigners. During her reign, the basic legal and economic questions about colonization were answered, and a government resolution encouraging settlement in Russia was sent to the Russian ambassadors living abroad on May 2, 1759. The active recruitment of colonists would have to wait until the conclusion of the Seven Year's War, which ended in 1763. Empress Elisabeth died on January 5, 1762, and would not see her colonization plans carried out.

Shortly after becoming the next Empress of Russia, Catherine II approved a new colonization policy designed to benefit her empire on October 14, 1762.

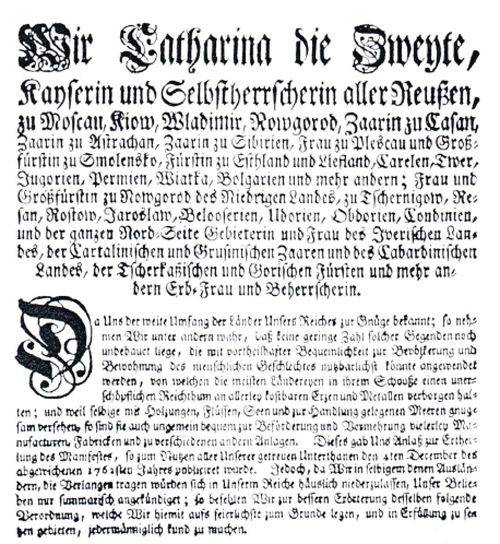

Catherine’s first Manifesto, issued on December 4, 1762, was printed in Russian, German, French, English, Polish, Czech, and Arabic. This Manifesto was largely symbolic, given that the Russian government had not yet established an administrative structure to plan and manage such an extensive colonization program.

Catherine’s second Manifesto was issued on July 22, 1763, at the end of the Seven Years' War. This Manifesto was perfectly timed to appeal to the war and tax-weary European populace. Copies of the Manifesto were printed in newspapers and on leaflets distributed throughout Europe, focusing on the German-speaking lands where much of the war had been fought. These lands had no national government and comprised many small principalities, counties, duchies, and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Some of these territories, such as the County of Isenburg, did not have legal restrictions preventing their subjects from traveling or migrating to new lands.

The second Manifesto was enhanced to make the offer more specific and attractive. Among the promises made to the colonists were exemption from military service, freedom of religion, a 30-year exemption from taxes, land provided at no cost, and travel expenses paid by the Russian government. At the time, and even by today's standards, this was a very enlightened and generous offer to prospective immigrants.

For decades, Russia had attempted to productively colonize its empire to the south after winning territory from the Ottoman Empire. The government felt that the area along the lower Volga River was unstable, and bands of roving bandits made settlement impossible. Catherine and her government wanted to solidify this region as Russian territory, and she needed free settlers who would turn the land into productive farms and serve as a model for native people living in the area.

An attempt was made to lure colonists to the region in 1731, but fears about the lack of military protection resulted in almost no interest. In 1732, Empress Anna Ivanova resettled a group of over 1,000 Don Cossack families along the lower Volga under the pretext of protecting and stabilizing the frontier. The Cossacks reportedly made poor colonists and often took part in looting the trade routes in the region.

Attempts in the 1740s to attract Russian subjects to the lower Volga were problematic as serfdom prevented the free movement of the general population. The serfs were bound to the landowners who had no interest in releasing their workers or weakening the class system. Landowners were reluctant to create new farms in the troubled region. As a result, the Russian government began to look beyond its borders for colonists.

Empress Elisabeth resolved the question of inviting foreigners. During her reign, the basic legal and economic questions about colonization were answered, and a government resolution encouraging settlement in Russia was sent to the Russian ambassadors living abroad on May 2, 1759. The active recruitment of colonists would have to wait until the conclusion of the Seven Year's War, which ended in 1763. Empress Elisabeth died on January 5, 1762, and would not see her colonization plans carried out.

Shortly after becoming the next Empress of Russia, Catherine II approved a new colonization policy designed to benefit her empire on October 14, 1762.

Catherine’s first Manifesto, issued on December 4, 1762, was printed in Russian, German, French, English, Polish, Czech, and Arabic. This Manifesto was largely symbolic, given that the Russian government had not yet established an administrative structure to plan and manage such an extensive colonization program.

Catherine’s second Manifesto was issued on July 22, 1763, at the end of the Seven Years' War. This Manifesto was perfectly timed to appeal to the war and tax-weary European populace. Copies of the Manifesto were printed in newspapers and on leaflets distributed throughout Europe, focusing on the German-speaking lands where much of the war had been fought. These lands had no national government and comprised many small principalities, counties, duchies, and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Some of these territories, such as the County of Isenburg, did not have legal restrictions preventing their subjects from traveling or migrating to new lands.

The second Manifesto was enhanced to make the offer more specific and attractive. Among the promises made to the colonists were exemption from military service, freedom of religion, a 30-year exemption from taxes, land provided at no cost, and travel expenses paid by the Russian government. At the time, and even by today's standards, this was a very enlightened and generous offer to prospective immigrants.

The following is a translation of the Manifesto of 1763.

We, Catherine the second, by the Grace of God, Empress and Autocrat of all the Russians at Moscow, Kiev, Vladimir, Novgorod, Czarina of Kasan, Czarina of Astrachan, Czarina of Siberia, Lady of Pleskow and Grand Duchess of Smolensko, Duchess of Estonia and Livland, Carelial, Tver, Yugoria, Permia, Viatka and Bulgaria and others; Lady and Grand Duchess of Novgorod in the Netherland of Chernigov, Resan, Rostov, Yaroslav, Beloosrial, Udoria, Obdoria, Condinia, and Ruler of the entire North region and Lady of the Yurish, of the Cartalinian and Grusinian czars and the Cabardinian land, of the Cherkessian and Gorsian princes and the lady of the manor and sovereign of many others. As We are sufficiently aware of the vast extent of the lands within Our Empire, We perceive, among other things, that a considerable number of regions are still uncultivated which could easily and advantageously be made available for productive use of population and settlement. Most of the lands hold hidden in their depth an inexhaustible wealth of all kinds of precious ores and metals, and because they are well provided with forests, rivers and lakes, and located close to the sea for purpose of trade, they are also most convenient for the development and growth of many kinds of manufacturing, plants, and various installations. This induced Us to issue the manifesto which was published last Dec. 4, 1762, for the benefit of all Our loyal subjects. However, inasmuch as We made only a summary announcement of Our pleasure to the foreigners who would like to settle in Our Empire, we now issue for a better understanding of Our intention the following decree which We hereby solemnly establish and order to be carried out to the full.

I. We permit all foreigners to come into Our Empire, in order to settle in all the governments, just as each one may desire.

II. After arrival, such foreigners can report for this purpose not only to the Guardianship Chancellery established for foreigners in Our residence, but also, if more convenient, to the governor or commanding officer in one of the border-towns of the Empire.

III. Since those foreigners who would like to settle in Russia will also include some who do not have sufficient means to pay the required travel costs, they can report to our ministers in foreign courts, who will not only transport them to Russia at Our expense, but also provide them with travel money.

IV. As soon as these foreigners arrive in Our residence and report at the Guardianship Chancellery or in a border-town, they shall be required to state their true decision whether their real desire is to be enrolled in the guild of merchants or artisans, and become citizens, and in what city; or if they wish to settle on free, productive land in colonies and rural areas, to take up agriculture or some other useful occupation. Without delay, these people will be assigned to their destination, according to their own wishes and desires. From the following register* it can be seen in which regions of Our Empire free and suitable lands are still available. However, besides those listed, there are many more regions and all kinds of land where We will likewise permit people to settle, just as each one chooses for his best advantage.

*The register lists the areas where the immigrants can be settled.

V. Upon arrival in Our Empire, each foreigner who intends to become a settler and has reported to the Guardianship Chancellery or in other border-towns of Our Empire and, as already prescribed in # 4, has declared his decision, must take the oath of allegiance in accordance with his religious rite.

VI. In order that the foreigners who desire to settle in Our Empire may realize the extent of Our benevolence to their benefit and advantage, this is Our will -- :

1. We grant to all foreigners coming into Our Empire the free and unrestricted practice of their religion according to the precepts and usage of their Church. To those, however, who intend to settle not in cities but in colonies and villages on uninhabited lands we grant the freedom to build churches and bell towers, and to maintain the necessary number of priests and church servants, but not the construction of monasteries. On the other hand, everyone is hereby warned not to persuade or induce any of the Christian co-religionists living in Russia to accept or even assent to his faith or join his religious community, under pain of incurring the severest punishment of Our law. This prohibition does not apply to the various nationalities on the borders of Our Empire who are attached to the Mahometan faith. We permit and allow everyone to win them over and make them subject to the Christian religion in a decent way.

2. None of the foreigners who have come to settle in Russia shall be required to pay the slightest taxes to Our treasury, nor be forced to render regular or extraordinary services, nor to billet troops. Indeed, everybody shall be exempt from all taxes and tribute in the following manner: those who have been settled as colonists with their families in hitherto uninhabited regions will enjoy 30 years of exemption; those who have established themselves, at their own expense, in cities as merchants and tradesmen in Our Residence St. Petersburg or in the neighboring cities of Livland, Estonia, Ingermanland, Carelia and Finland, as well as in the Residential city of Moscow, shall enjoy 5 years of tax-exemption. Moreover, each one who comes to Russia, not just for a short while but to establish permanent domicile, shall be granted free living quarters for half a year.

3. All foreigners who settle in Russia either to engage in agriculture and some trade, or to undertake to build factories and plants will be offered a helping hand and the necessary loans required for the construction of factories useful for the future, especially of such as have not yet been built in Russia.

4. For the building of dwellings, the purchase of livestock needed for the farmstead, the necessary equipment, materials, and tools for agriculture and industry, each settler will receive the necessary money from Our treasury in the form of an advance loan without any interest. The capital sum has to be repaid only after ten years, in equal annual instalments in the following three years.

5. We leave to the discretion of the established colonies and village the internal constitution and jurisdiction, in such a way that the persons placed in authority by Us will not interfere with the internal affairs and institutions. In other respects the colonists will be liable to Our civil laws. However, in the event that the people would wish to have a special guardian or even an officer with a detachment of disciplined soldiers for the sake of security and defense, this wish would also be granted.

6. To every foreigner who wants to settle in Russia We grant complete duty-free import of his property, no matter what it is, provided, however, that such property is for personal use and need, and not intended for sale. However, any family that also brings in unneeded goods for sale will be granted free import on goods valued up to 300 rubles, provided that the family remains in Russia for at least 10 years. Failing which, it be required, upon its departure, to pay the duty both on the incoming and outgoing goods.

7. The foreigners who have settled in Russia shall not be drafted against their will into the military or the civil service during their entire stay here. Only after the lapse of the years of tax-exemption can they be required to provide labor service for the country. Whoever wishes to enter military service will receive, besides his regular pay, a gratuity of 30 rubles at the time he enrolls in the regiment.

8. As soon as the foreigners have reported to the Guardianship Chancellery or to our border towns and declared their decision to travel to the interior of the Empire and establish domicile there, they will forthwith receive food rations and free transportation to their destination.

9. Those among the foreigners in Russia who establish factories, plants, or firms, and produce goods never before manufactured in Russia, will be permitted to sell and export freely for ten years, without paying export duty or excise tax.

10. Foreign capitalists who build factories, plants, and concerns in Russia at their own expense are permitted to purchase serfs and peasants needed for the operation of the factories.

11. We also permit all foreigners who have settled in colonies or villages to establish market days and annual market fairs as they see fit, without having to pay any dues or taxes to Our treasury.

VII. All the afore-mentioned privileges shall be enjoyed not only by those who have come into our country to settle there, but also their children and descendants, even though these are born in Russia, with the provision that their years of exemption will be reckoned from the day their forebears arrived in Russia.

VIII. After the lapse of the stipulated years of exemption, all the foreigners who have settled in Russia are required to pay the ordinary moderate contributions and, like our other subjects, provide labor- service for their country. Finally, in the event that any foreigner who has settled in Our Empire and has become subject to Our authority should desire to leave the country, We shall grant him the liberty to do so, provided, however, that he is obligated to remit to Our treasury a portion of the assets he has gained in this country; that is, those who have been here from one to five years will pay one-fifth, whole those who have been here for five or more years will pay one-tenth. Thereafter each one will be permitted to depart unhindered anywhere he pleases to go.

IX. If any foreigner desiring to settle in Russia wishes for certain reasons to secure other privileges or conditions besides those already stated, he can apply in writing or in person to our Guardianship Chancellery, which will report the petition to Us. After examining the circumstances, We shall not hesitate to resolve the matter in such a way that the petitioner's confidence in Our love of justice will not be disappointed.

Given at the Court of Peter, July 22, 1763

in the Second Year of Our Reign.

The original was signed by Her Imperial Supreme Majesty's own hand.

Printed by the Senate, July 25, 1763

This translation was made by Fred C. Koch from a German text that was published in "Volk auf dem Weg", June 1962. The original document is held in the Stadtarchiv of Ulm, Germany.

The Manifesto of 1763 greatly appealed to many seeking a better life. Over 30,000 people began their migration to Russia between 1763 and 1766.

An Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers was established under Catherine's trusted friend, Count Grigory Orlov, to plan and administer the colonization program. The Guardianship reported directly to Catherine, and Count Orlov wrote about the conditions in Norka in 1769.

The Manifesto was soon followed by many supplementary stipulations. On February 19, 1764, Catherine approved the "agrarian law" for the colonists, which was developed by Grigory Orlov. The law defined the settlement's primary conditions and the foreign settlers' organization.

Several provisions of the 1763 Manifesto were never truly fulfilled, such as the promise that colonists could settle anywhere in the Russian Empire, including towns and cities, and practice their trade. After arriving in Russia, nearly all the colonists were directed to settle in the Volga region near Saratov, where they would primarily work as farmers and practice their trade as time allowed.

After more than 100 years of settlement in Russia, the remaining provisions of the 1763 Manifesto were revoked between 1871 and 1874. The loss of the privileges promised by Catherine sparked another large-scale migration of these ethnic Germans, this time to the Americas.

An Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers was established under Catherine's trusted friend, Count Grigory Orlov, to plan and administer the colonization program. The Guardianship reported directly to Catherine, and Count Orlov wrote about the conditions in Norka in 1769.

The Manifesto was soon followed by many supplementary stipulations. On February 19, 1764, Catherine approved the "agrarian law" for the colonists, which was developed by Grigory Orlov. The law defined the settlement's primary conditions and the foreign settlers' organization.

Several provisions of the 1763 Manifesto were never truly fulfilled, such as the promise that colonists could settle anywhere in the Russian Empire, including towns and cities, and practice their trade. After arriving in Russia, nearly all the colonists were directed to settle in the Volga region near Saratov, where they would primarily work as farmers and practice their trade as time allowed.

After more than 100 years of settlement in Russia, the remaining provisions of the 1763 Manifesto were revoked between 1871 and 1874. The loss of the privileges promised by Catherine sparked another large-scale migration of these ethnic Germans, this time to the Americas.

Sources

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Printed by Augstums Printing Service, 2005. 84-86. Print.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 192-94. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. 219-42. Print.

"The History of the Russian Germans (Russian Language)." RusDeutsch. Web. 30 Nov. 2005. <http://www.rusdeutsch.ru/?hist=1&hmenu01=7&hmenu0=2>.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 192-94. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. 219-42. Print.

"The History of the Russian Germans (Russian Language)." RusDeutsch. Web. 30 Nov. 2005. <http://www.rusdeutsch.ru/?hist=1&hmenu01=7&hmenu0=2>.

Last updated November 21, 2023