Community > Agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture was the primary economic activity that sustained the colony of Norka from its founding in 1767 to its demise in 1941.

Although the Russian government persuaded some of the German craftsmen to take up agriculture, the list of first colonists for Norka shows that most adult males were already farmers from the areas of Hessen or Isenburg in what is now central Germany. According to the census lists, the vast majority of colonists remained farmers in Russia in the early years of settlement, although some would move to other forms of industry in later years. Given that the government provided most of the material needs in the early years, there was initially a limited market for craft goods. As a result, most of the colonists focused on the development of agriculture to sustain themselves and their new community.

The first years after settlement in 1767 resulted in a number of poor harvests, the result of not understanding the climatic conditions, a series of dry years, and the Pugachev raid in 1774. In 1774, the Russian government was forced to provide substantial aid to the colonists in the form of seed grain, materials for housing and buildings, and additional animal stock. Norka and other colonies suffered from both the theft of horses and diseased cows.

Despite some of the struggles during the early years of settlement, Norka may have been more fortunate than many colonies. In 1773, Peter Simon Pallas reported on what he observed in the colonies of Norka and Huck:

Despite some of the struggles during the early years of settlement, Norka may have been more fortunate than many colonies. In 1773, Peter Simon Pallas reported on what he observed in the colonies of Norka and Huck:

"These colonies have since their founding produced their own grain not only for food, but for sale. They have procured for themselves all sorts of convenience and have even built their own granaries."

The first years of poor harvests in the colonies ended in 1775. This first high yield crop was made possible by adequate rainfall for the first time after many years of drought. In addition, the colonists began to plow more acreage when they replaced their crude Russian sokhi (wooden plows) with iron-tipped plows. The colonists also became adept at breeding draft horses to pull the tilling equipment. Commercial fertilizers were unknown and the farmers practiced a three and four year crop rotation. Several vast fields were maintained around each colony to insure adequate supplies of each agricultural commodity.

In December 1774, a decision was made to build a system of magaziny, which were used to store grain reserves. Each family was required to put aside seed grain in this community store. The store was under the control of a Russian commissar and the village authorities. Due to a lack of funding for building the storage units (known as "magazines"), seed grain was often stored in barns, empty structures, and even houses. By 1781, the stores had been constructed in all of the colonies. At this time, it was decided the reserves for food would also be established. From 1781, one-tenth of the harvest was kept in reserve. The stores proved to be a great success. From the time of their implementation until the dissolution of the Office of Oversight in the 1870's, there was not a single case of famine in the colonies despite their location in a risky agricultural zone.

In December 1774, a decision was made to build a system of magaziny, which were used to store grain reserves. Each family was required to put aside seed grain in this community store. The store was under the control of a Russian commissar and the village authorities. Due to a lack of funding for building the storage units (known as "magazines"), seed grain was often stored in barns, empty structures, and even houses. By 1781, the stores had been constructed in all of the colonies. At this time, it was decided the reserves for food would also be established. From 1781, one-tenth of the harvest was kept in reserve. The stores proved to be a great success. From the time of their implementation until the dissolution of the Office of Oversight in the 1870's, there was not a single case of famine in the colonies despite their location in a risky agricultural zone.

In April 1775, with a growing number of loans made to the colonists, the Kontora in Saratov ordered that a census revision be made to identify those who were capable and incapable of farming. It should be noted that the incapable were largely elderly and invalids. In the future, government loans in the form of money, horses, cows, plows, carts, scythes, clothing, and other necessities would only be made to those capable of farming. The government also demanded that a collective guarantee of the loans be made by each colony and even the clergy were enlisted to persuade the colonists to accept this unpopular stipulation. Failure to accept collective responsibility was punished by whipping. Despite these harsh measures it took several years for the colonists to acquiesce to this arrangement.

There were also those with a trade specialty that did not wish to farm. These people were provided with passports and allowed to work in cities to pay off their debts to the state.

The remaining people who were capable of work, but chose not to work, were threatened with banishment to Astrakhan to reduce the burden they placed on others.

Although the colonists were required to pay their debts to the Russian government within 10 years after settlement, this was not possible. Accounts of the debt varied widely and were not kept by household. Repayment extensions were made and by 1800 very few families had the ability to repay their loans.

Despite their early struggles, the Volga Germans had achieved great success in farm production by 1800 and this success would continue through the next 140 years.

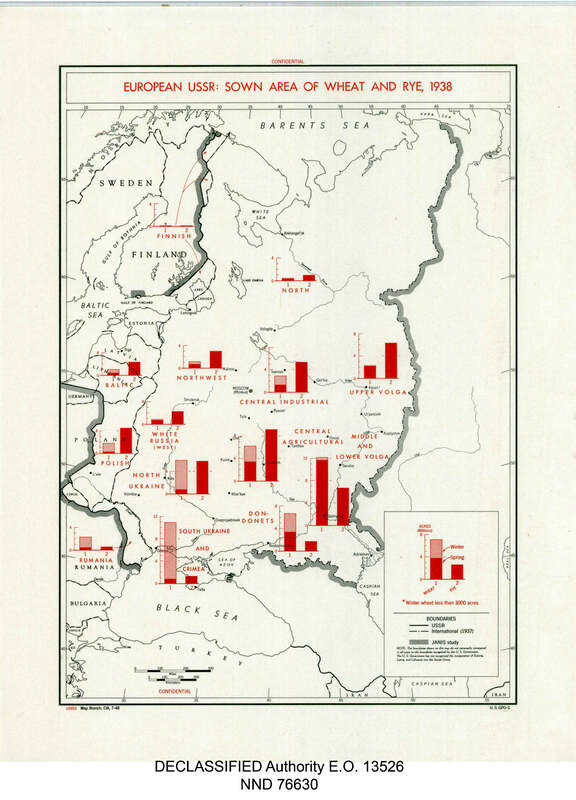

The Volga region is one of the most important grain producing regions in Russia and throughout the world. In the 19th century, Russia was the leader in the world export of rye and barley, and it played a significant role as a supplier of wheat and oats. Grain exports accounted for about about half the value of all Russian exports.

There were also those with a trade specialty that did not wish to farm. These people were provided with passports and allowed to work in cities to pay off their debts to the state.

The remaining people who were capable of work, but chose not to work, were threatened with banishment to Astrakhan to reduce the burden they placed on others.

Although the colonists were required to pay their debts to the Russian government within 10 years after settlement, this was not possible. Accounts of the debt varied widely and were not kept by household. Repayment extensions were made and by 1800 very few families had the ability to repay their loans.

Despite their early struggles, the Volga Germans had achieved great success in farm production by 1800 and this success would continue through the next 140 years.

The Volga region is one of the most important grain producing regions in Russia and throughout the world. In the 19th century, Russia was the leader in the world export of rye and barley, and it played a significant role as a supplier of wheat and oats. Grain exports accounted for about about half the value of all Russian exports.

Rainfall in Norka is light and occurs variably during the summer months. The geographic coordinates are 51° 09' North latitude and 45° 18' East longitude. Norka is about as far north as Saskatoon, Canada with a similar climate and relative short growing season of about 106 days (about 170 days is considered ideal). Located near the Karamysh River, the chernozem soil is rich and fertile, excellent for growing grain.

In 1814-1815, Heuschrecken (grasshoppers) devoured all of the crops.

By 1859, the allotted arable land for the colony was about 12,460 dessiatines (33,642 acres). The soil is mostly chernozem (black earth). Under the Mir system of communal land ownership, the arable land was divided equally between males, each one having 3 dessiatines (8.1 acres). The land was allocated in sections based on soil quality and distance from the village. Each household had the right to claim one or more strips from each section depending on the number of adults in the household. The purpose of this allocation was not so much social (to each according to his needs) as it was practical (that each person pay his taxes). Strips were periodically re-allocated on the basis of a census, to ensure equitable share of the land. This was enforced by the state, which had an interest in the ability of households to pay their taxes. While equitable, this system of land allocation often meant that farmers had to travel long distances from home to their fields.

By 1859, the allotted arable land for the colony was about 12,460 dessiatines (33,642 acres). The soil is mostly chernozem (black earth). Under the Mir system of communal land ownership, the arable land was divided equally between males, each one having 3 dessiatines (8.1 acres). The land was allocated in sections based on soil quality and distance from the village. Each household had the right to claim one or more strips from each section depending on the number of adults in the household. The purpose of this allocation was not so much social (to each according to his needs) as it was practical (that each person pay his taxes). Strips were periodically re-allocated on the basis of a census, to ensure equitable share of the land. This was enforced by the state, which had an interest in the ability of households to pay their taxes. While equitable, this system of land allocation often meant that farmers had to travel long distances from home to their fields.

The system of land management was a primarily a three-field rotation. Some households rented land in 1887. The rental price for winter field land was 8 rubles per dessiatine, the price for spring field rental was 6 rubles per dessiatine. Land could also be rented from other settlers, which was a common practice.

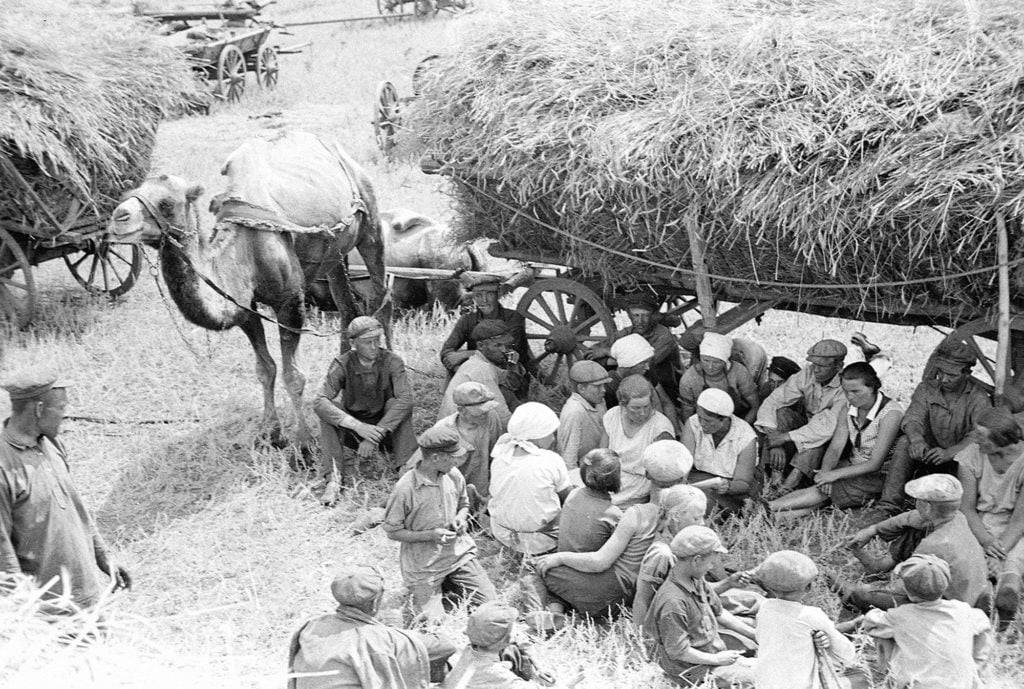

Farm work began in the spring as the snows melted and revealed a growth of winter rye in at least one of the large colony fields. Prior to beginning their spring plowing, the farmers gathered at the church for a prayer service (Ackerbestunde).

Volga Germans were heavy consumers of rye flour, and it was planted in late August following summer rains. Sunflowers, spring grains, and potatoes were planted in late March and April. Sunflowers were processed for oil in various mills in the region. Millet was the third most important grain crop in the colonies and was also sown in the spring. Millet was used to make Hirsche, a coarse porridge. Oats, barley, both used mostly as animal fodder, were also spring crops.

Farm work began in the spring as the snows melted and revealed a growth of winter rye in at least one of the large colony fields. Prior to beginning their spring plowing, the farmers gathered at the church for a prayer service (Ackerbestunde).

Volga Germans were heavy consumers of rye flour, and it was planted in late August following summer rains. Sunflowers, spring grains, and potatoes were planted in late March and April. Sunflowers were processed for oil in various mills in the region. Millet was the third most important grain crop in the colonies and was also sown in the spring. Millet was used to make Hirsche, a coarse porridge. Oats, barley, both used mostly as animal fodder, were also spring crops.

Hemp and flax were also grown for domestic clothing needs. Cabbage, melons, and pumpkins were gathered from communal garden near the villages. Sauerkraut, a staple food for the Volga Germans, was prepared in the fall. Some people planted garden vegetables in the Hinnerhof (the yard adjacent to each home) including: carrots, onions, sugar beets, tomatoes, and cucumbers. Apple, pear, and cherry trees were planted in both family gardens and large communal orchards. Conrad Brill notes that there was a large plot of potato land near Rybushka. Most fruits were preserved through sun-drying. Wild pear trees and strawberries were common. Other berry varieties were also available. Mushrooms were harvested in August. Licorice root, harvested in the fall, was used to make Steppetee - a favorite Volga German drink.

In Norka, forty-eight families cultivated tobacco until 1780 when a monopoly of buyers forced the price down to a point where it no longer made economic sense to continue.

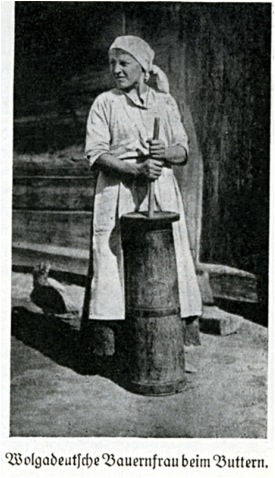

Large cellars were constructed and filled with irregular blocks of ice insulated with straw to keep dairy products and fresh meat safely stored in the hot summer months. The ice was collected early in the year along the banks of the Volga and in the mill ponds during the spring thaw.

Families gathered for an annual butchering bee in November or early December. Fruit tree cuttings were used to smoke sausage and other meat products made by the colonists.

With the long harvest season over, fall plantings completed, and produce sold or stored, the villagers gathered to celebrate their bounty in an exuberant festival, the Kerb. This event signaled the end of the field season as the people prepared for the long Russian winter. Isolated on the steppe, the Volga German villages became quiet and self-sufficient until the next spring.

With the arrival of winter snow and ice, wagons were stored in sheds. The wheels were removed and leaned against a wall. The wagon boxes were stacked to use space efficiently.

In Norka, forty-eight families cultivated tobacco until 1780 when a monopoly of buyers forced the price down to a point where it no longer made economic sense to continue.

Large cellars were constructed and filled with irregular blocks of ice insulated with straw to keep dairy products and fresh meat safely stored in the hot summer months. The ice was collected early in the year along the banks of the Volga and in the mill ponds during the spring thaw.

Families gathered for an annual butchering bee in November or early December. Fruit tree cuttings were used to smoke sausage and other meat products made by the colonists.

With the long harvest season over, fall plantings completed, and produce sold or stored, the villagers gathered to celebrate their bounty in an exuberant festival, the Kerb. This event signaled the end of the field season as the people prepared for the long Russian winter. Isolated on the steppe, the Volga German villages became quiet and self-sufficient until the next spring.

With the arrival of winter snow and ice, wagons were stored in sheds. The wheels were removed and leaned against a wall. The wagon boxes were stacked to use space efficiently.

When Volga Germans became rich enough to want to leave their villages and set up as independent farmers, instead of operating as communal village farmers, they bought themselves land, but usually named the farms (known as Chutor or Khutor) after their own surname - e.g. Diesendorf, Schmidt, Seiffert. A Khutor was a small settlement or outpost beyond the boundaries of the colony. Some Norkans lived in Rybushka Khutor just north of Norka and near the Russian village of Rybushka. They might very well have taken extended families along with them, or field labor employees, or other poorer families to work the land, so it would essentially become a 'farmstead.'

The following agricultural data for the Saratov Province was published by the author L. Lichkov:

The following agricultural data for the Saratov Province was published by the author L. Lichkov:

In 1886, 50 percent of the land in Norka was rented. At the same time 41 percent of the land owners leased sites. Norka is a rich village. In 1890, of the 26 villages in Kamyshin District, only 4, including Norka, paid taxes on time to the state.

In the years 1886-87, from 11 colonies of the Kamyshin District, 214 families left for America.

There were very high rates of growth in the population of the colonies. From 1834 to 1850 in the central areas of Russia, the average increase per 1,000 of population was 50 to 70 persons, in the Volga German region there average increase was 500 people per 1,000 of population.

Sources

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Lichkov, L. The Collection of Statistical Data on the Saratov Province. Volume 11. Kamyshinsky District. Saratov, 1886.

Minkh, A. N. Historical and Geographical Dictionary of the Saratov Province. Saratov, 1898. 688-691. Print.

Moon, David. The Plough That Broke the Steppes: Agriculture and Environment on Russia's Grasslands, 1700-1914. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013. Print.

Lichkov, L. The Collection of Statistical Data on the Saratov Province. Volume 11. Kamyshinsky District. Saratov, 1886.

Minkh, A. N. Historical and Geographical Dictionary of the Saratov Province. Saratov, 1898. 688-691. Print.

Moon, David. The Plough That Broke the Steppes: Agriculture and Environment on Russia's Grasslands, 1700-1914. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013. Print.

Last updated March 17, 2022.