Community > Cottage Industries > Mills

Mills

From the early years of settlement, milling grain became an essential industry in the Volga German colonies that allowed the economy and colonies to develop. In 1769, only two years after the founding of Norka, Count Grigory Orlov reported that there were two wheat mills and six rye mills.

During his expedition through central Russia, Peter Simon Pallas visited the German colonies of Norka and Huck in August 1773. He was clearly impressed with what he saw when he recorded these comments only six years after the founding of Norka:

During his expedition through central Russia, Peter Simon Pallas visited the German colonies of Norka and Huck in August 1773. He was clearly impressed with what he saw when he recorded these comments only six years after the founding of Norka:

These colonies have since their founding produced their own grain not only for food, but for sale. They have procured for themselves all sorts of convenience and have even built their own granaries.

Both the 1775 and 1798 censuses note that mills were operating in Norka.

Amelia Werre (née Krieger) tells a story about how her grandfather, Nicholas Krieger (born 1839), became a mill operator and owner:

Amelia Werre (née Krieger) tells a story about how her grandfather, Nicholas Krieger (born 1839), became a mill operator and owner:

It was the custom in a household that the sons married and remained under their father's roof, but the father ruled over the whole household, no matter how old the sons were. Only in homes where there were no sons was this rule reversed. This was the case of my paternal grandfather, Nicholas Krieger. He married a Katherine Schneider and made his home with them. They had a flour mill and my father and his two younger brothers and two sisters were born and raised in its living quarters. My father learned to operate the flour mill at an early age, and at the death of his father in April 1885, took over the operation of the mill and the farming likewise as he was the oldest.

Jacob Miller (born 1871) recalls a mill on his father's farm near Norka.

I was confirmed at the age of 14, and at that time my father had leased a farm away from the colony. In connection with the farm was a small water power flour mill which only ground about 75 bushels of grain in 24 hours. Besides this we kept cattle and sheep, and hogs. Since the land was very productive we were doing very well.

By 1898, A. N. Minkh reported that there were 54 enterprises in Norka, including six windmills for grain and six oil mills.

Conrad Brill mentions several Norka businesses in his story titled Memories of Norka. Brill's brother-in-law was known as Reiche (Rich) Schleuning (also Schleining). Schleuning was reportedly one of the wealthiest men in Norka in the early 1900s. In addition to farming his extensive land holdings with 25 teams of horses, he also owned a mill, the Lafka (a general store), orchards, and vegetable gardens.

Peter Sinner operated a large mill in Norka. It was reportedly four or five stories high and powered by electricity from two large generators driven by flowing water. The year 1899 was displayed on the highest level of the mill. Mr. Sinner employed about 20 people at busy times of the year.

Conrad Brill mentions several Norka businesses in his story titled Memories of Norka. Brill's brother-in-law was known as Reiche (Rich) Schleuning (also Schleining). Schleuning was reportedly one of the wealthiest men in Norka in the early 1900s. In addition to farming his extensive land holdings with 25 teams of horses, he also owned a mill, the Lafka (a general store), orchards, and vegetable gardens.

Peter Sinner operated a large mill in Norka. It was reportedly four or five stories high and powered by electricity from two large generators driven by flowing water. The year 1899 was displayed on the highest level of the mill. Mr. Sinner employed about 20 people at busy times of the year.

At one point in time, Sinner owned three water-wheel-powered mills. One of the mills was located at Goschgoverna, on the Medveditsa River east of Norka, which had a conveyor system on which bags of grain were unloaded, and the milled flour came back in bags via the conveyor.

The customary price for grinding flour in the first quarter of the 1900s was one scoop for the mill for every pud (36 pounds) that was processed.

In 1910, Peter Sinner proposed putting street lights throughout Norka. He told the town council that if they would buy and set up the poles and electrical wires, he would supply the lights and electrical power from the generators at his mill. There was much discussion on the proposal, which was ultimately voted down. The poorer people in the village volunteered to do the work but could not contribute money. The wealthier people thought Mr. Sinner was trying to make himself richer by selling electricity. Sinner was already wealthy by local standards and was active in banking and other ventures in addition to the mill. Sinner also had the biggest home in Norka at that time.

The customary price for grinding flour in the first quarter of the 1900s was one scoop for the mill for every pud (36 pounds) that was processed.

In 1910, Peter Sinner proposed putting street lights throughout Norka. He told the town council that if they would buy and set up the poles and electrical wires, he would supply the lights and electrical power from the generators at his mill. There was much discussion on the proposal, which was ultimately voted down. The poorer people in the village volunteered to do the work but could not contribute money. The wealthier people thought Mr. Sinner was trying to make himself richer by selling electricity. Sinner was already wealthy by local standards and was active in banking and other ventures in addition to the mill. Sinner also had the biggest home in Norka at that time.

Around 1913, a man named Miller from the colony of Kutter came to Norka and offered his farmland in trade for the Norka mill. Peter Sinner accepted the offer. Sinner bought a beer tavern in the Mitteldorf (town center) and tore it down so he could build a new house for his daughter, Mollie, and her husband who was one of Sinner's hired men.

Poste (postman) Krieger gave up his position as the mail carrier for Norka and decided to build a windmill to grind flour.

A Giebelhaus family owned a picturesque windmill on the grain lands north of the colony.

Poste (postman) Krieger gave up his position as the mail carrier for Norka and decided to build a windmill to grind flour.

A Giebelhaus family owned a picturesque windmill on the grain lands north of the colony.

Another windmill was operated by Jacob Weidenkeller (born September 13, 1874), who was known as Windmühle (Windmill) Weidenkeller. The Weidenkeller windmill was located northeast of Norka, but it was too close to high ground around it, so it didn't receive sufficient wind, and its use was discontinued. Old-timers used to joke about Weidenkeller building a "mill behind a hill" so he wouldn't have to work so hard. The windmills were said to be less reliable and profitable than the water-powered mills closer to the village.

Millwork could be dangerous. Ludwig Georg Ross (born August 24, 1816) died of suffocation from fumes inside a windmill in Norka on February 5, 1852.

Conrad Schreiber and his four sons owned and operated a large flour mill in a Russian village named Dimitriyevka on the Karamysh River north of Norka. The family lived in a large compound in Dimitriyevka and had servants. Despite living far from Norka, they often traveled there for church services and special occasions. The Schreibers also frequently traveled to Saratov, where they shopped and attended the theater.

A Hefeneider family reportedly owned three water-powered mills in Russian villages near Saratov. This family lived in one of the largest homes in Norka.

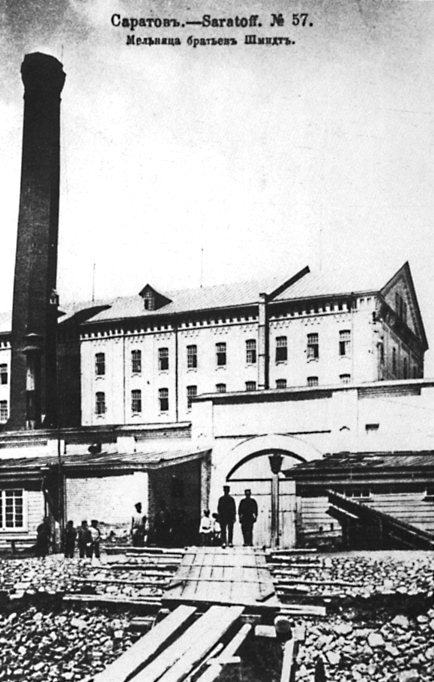

Until 1917, flour milling was almost equally divided between the large commercial operations, such as those in Saratov, that served urban markets and the small wind and water-powered mills that served local markets. Historian James Long states, "Saratov was the Minneapolis of the Lower Volga, and the Volga Germans were the Pillsburys of the flour milling industry." The Borel, Reinecke, and Schmidt families, who controlled much of the commercial milling market, became wealthy industrialists.

Millwork could be dangerous. Ludwig Georg Ross (born August 24, 1816) died of suffocation from fumes inside a windmill in Norka on February 5, 1852.

Conrad Schreiber and his four sons owned and operated a large flour mill in a Russian village named Dimitriyevka on the Karamysh River north of Norka. The family lived in a large compound in Dimitriyevka and had servants. Despite living far from Norka, they often traveled there for church services and special occasions. The Schreibers also frequently traveled to Saratov, where they shopped and attended the theater.

A Hefeneider family reportedly owned three water-powered mills in Russian villages near Saratov. This family lived in one of the largest homes in Norka.

Until 1917, flour milling was almost equally divided between the large commercial operations, such as those in Saratov, that served urban markets and the small wind and water-powered mills that served local markets. Historian James Long states, "Saratov was the Minneapolis of the Lower Volga, and the Volga Germans were the Pillsburys of the flour milling industry." The Borel, Reinecke, and Schmidt families, who controlled much of the commercial milling market, became wealthy industrialists.

The colonists found the rural mills more to their liking as it was cheaper to mill and sell their own grain. By 1855, there were 157 mills on the Volga's Bergseite (hilly side), including those in Norka. An 1872 survey found that the colonists owned 17 of the 50 largest mills and produced 45 percent of the flour in Saratov Province. The smaller mills were not considered a threat to the large industrial mills as they operated at a low cost and milled a coarser wheat flour along with rye flour that was more to the liking of the local population.

The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 created a dangerous situation for mill owners who were considered kulaks or class enemies of the poor. Mills were often confiscated from their owners and placed under Soviet authority. The large mill built by Peter Sinner in 1899 was destroyed by the Communists. Other mills in Norka likely suffered the same fate.

In a letter to his relatives living in the United States (published in Die Welt-Post), Johann Georg Feuerstein describes the impact of the revolution, civil war, and the severe famine from 1921-1924 on the mills in Norka:

The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 created a dangerous situation for mill owners who were considered kulaks or class enemies of the poor. Mills were often confiscated from their owners and placed under Soviet authority. The large mill built by Peter Sinner in 1899 was destroyed by the Communists. Other mills in Norka likely suffered the same fate.

In a letter to his relatives living in the United States (published in Die Welt-Post), Johann Georg Feuerstein describes the impact of the revolution, civil war, and the severe famine from 1921-1924 on the mills in Norka:

I labored at the mill, but for now the mills are all quiet because there is nothing to mill. Thousands of people walk around like ghosts and die of starvation. The bells toll continuously. Many people are buried without coffins and others lay in the hedges and pathways and are not buried at all.

Sources

The 1775 and 1798 Censuses of the German Colony on the Volga, Norka: Also Known as Weigand. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1995. Print.

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 102-109. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan. 1798 Census of the German Colonies along the Volga: Economy, Population, and Agriculture. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1999. Print.

Minkh, A. N. Istoriko-geograficheskīĭ Slovarʹ Saratovskoĭ Gubernīi. Trans. Lyudmila Koretnikov. Saratov: Tip-īi︠a︡ Gubernskogo Zemstva, 1898. Print.

Orlov, Grigory Grigoryevich, Report of Conditions of Settlements on the Volga to Catherine II, February 14, 1769. Translation courtesy of Bill Pickelhaupt.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown.

Letter from Jacob Weidenkeller to Wilhelm Weidenkeller. Published in Die Welt-Post on August 17, 1916.

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 102-109. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan. 1798 Census of the German Colonies along the Volga: Economy, Population, and Agriculture. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1999. Print.

Minkh, A. N. Istoriko-geograficheskīĭ Slovarʹ Saratovskoĭ Gubernīi. Trans. Lyudmila Koretnikov. Saratov: Tip-īi︠a︡ Gubernskogo Zemstva, 1898. Print.

Orlov, Grigory Grigoryevich, Report of Conditions of Settlements on the Volga to Catherine II, February 14, 1769. Translation courtesy of Bill Pickelhaupt.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown.

Letter from Jacob Weidenkeller to Wilhelm Weidenkeller. Published in Die Welt-Post on August 17, 1916.

Last updated December 4, 2023