- Home

- People

- Community

-

History

- Timeline

- Origins of the Colonists

- Catherine's Manifesto 1763

- Why go to Russia?

- Recruitment 1766

- Planning 1764-1766

- Marriages Prior To Emigration 1766

- Voyage to Russia 1766 >

- Journey 1766-1767

- Founding of Norka 1767

- Early Years 1767-1769

- Norka 1769

- Pallas Report 1773

- Pugachev Raid 1774

- Norka 1775

- Norka 1798

- Norka 1811

- Napoleons Soldiers

- Norka 1834

- Daughter Colonies 1850s >

- Privileges Lost 1871-1874

-

Immigration 1875-1924

>

- Famine 1891-1892

- Norka 1898

- War & Turnoil 1904-1906

- World War 1914-1918

- Revolution & War 1917-1922

- Soviet Rule 1918-1941

- Famine 1921-1924

- Famine 1932-1933

- The Great Terror 1936-1938

- Deportation 1941

- Repression 1941-1956

- Cultural Loss 1957-2006

- A Culture in Peril

- Recent Times

- Traditions

-

Religion

- Resources

History > Deportation 1941

Deportation 1941

"Deportation was a kind of genocide, murder not of persons, but of a nations sense of itself." -- Susan Wise Bauer

On August 28, 1941, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet issued a Ukaz (decree) attempting to provide a legal basis for the decision to deport the ethnic Germans of the Volga German ASSR (Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic), the Saratov Oblast (Province), and the Stalingrad Oblast. The decision had already been made by the Council of People's Commissars and Central Committee of the Communist Party two days earlier. This forced expulsion brought an end to German life in Norka and all the Volga German settlements that began over 175 years earlier under Catherine the Great's Manifesto.

Tensions between the ethnic Germans living in Russia and their Russian counterparts had a long history. Generally, the Germans residing in Norka lived peacefully with their Russian neighbors. Still, stories told by Norka native Conrad Brill, who served in the Russian army before immigrating to the United States, illustrate underlying tensions between the ethnic groups. In describing Norka, Brill writes:

Tensions between the ethnic Germans living in Russia and their Russian counterparts had a long history. Generally, the Germans residing in Norka lived peacefully with their Russian neighbors. Still, stories told by Norka native Conrad Brill, who served in the Russian army before immigrating to the United States, illustrate underlying tensions between the ethnic groups. In describing Norka, Brill writes:

“The Karamysh River ran north and south between Beideck and Norka, but up north it veered or turned westward, so it bordered what was considered two sides of the Norka ground, the eastern edge and also the northern edge. Across the river on northern shore, was a Russian village named Rybushka that we traveled through when going toward Saratov….. To the west we bordered with Russian villages on the Medveditsa River. Along the Karamysh River, across from Rybushka, the land lying along the river was owned by four parties (including a Miller and Sinner family)... this we used for our potato ground. These four parcels of land far exceeded the amount of land farmed by all of the Russian villagers of the village of Rybushka, and created anxiety with the Russian villages near and far.”

Brill continues with a related story from his memoirs:

“A man named Soujac Krieger was the man who did the whipping when someone was sentenced to public punishment. Disgruntled Russians he had whipped gave the name to him. He had a horse shot out from under him in a skirmish with Russians from Rybushka during a dispute over the former ground used for the potato crop of Norka folk that was awarded to Rybushka villagers about the time of WWI and the Revolution.”

While these stories are isolated incidents, they help explain the sometimes bitter feelings that Russians felt towards their German neighbors, whom they viewed as separate and privileged.

Prejudice against the German colonists grew among segments of Russia’s population during the second half of the 19th century. The German agricultural settlements were often more prosperous than their Russian and Ukrainian neighbors. This economic success, combined with special privileges such as exemption from the draft, created envy and resentment among some Slavs.

The rise of Russian nationalism in the late 19th century intensified these anti-German sentiments. During this time, the Slavophile movement in Russia cast all ethnic Germans as their mortal enemy and the Volga Germans as a serious threat to the security of the empire. The Slavophile press consistently scapegoated the Volga Germans and other German communities in the Russian Empire. The consistent demonization of the Germans by the Slavophile press influenced even the highest levels of the Russian government.

During the 1870s, Tsar Alexander II began to revoke the rights of the German communities in the Russian Empire. In 1871, they lost the right to self-government. Three years later, Tsar Alexander II rescinded the immunity from military conscription granted to ethnic Germans by Catherine II (Catherine the Great). The loss of these rights inspired many ethnic Germans to emigrate from the Russian Empire to the United States, Canada, and South America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Large German communities, however, remained in the Volga, Ukraine, Black Sea region, Crimea, Caucasus, and other areas of the Russian Empire.

The First World War exacerbated Russia’s anti-German and pro-Russian tendencies. During this time, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov called for a “final solution” to the ethnic German problem in Russia, noting that the time had come ". . . to deal with this long over-due problem, for the current war has created the conditions to make it possible to solve this problem once and for all.”

The Germans living in Volhynia (in the north-western part of Ukraine) were the first to suffer deportation in 1915 under the Tsar. However, the Bolsheviks, who had begun to take power in Russia, rescinded a decree the following year that would have expelled the Volga Germans.

Prejudice against the German colonists grew among segments of Russia’s population during the second half of the 19th century. The German agricultural settlements were often more prosperous than their Russian and Ukrainian neighbors. This economic success, combined with special privileges such as exemption from the draft, created envy and resentment among some Slavs.

The rise of Russian nationalism in the late 19th century intensified these anti-German sentiments. During this time, the Slavophile movement in Russia cast all ethnic Germans as their mortal enemy and the Volga Germans as a serious threat to the security of the empire. The Slavophile press consistently scapegoated the Volga Germans and other German communities in the Russian Empire. The consistent demonization of the Germans by the Slavophile press influenced even the highest levels of the Russian government.

During the 1870s, Tsar Alexander II began to revoke the rights of the German communities in the Russian Empire. In 1871, they lost the right to self-government. Three years later, Tsar Alexander II rescinded the immunity from military conscription granted to ethnic Germans by Catherine II (Catherine the Great). The loss of these rights inspired many ethnic Germans to emigrate from the Russian Empire to the United States, Canada, and South America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Large German communities, however, remained in the Volga, Ukraine, Black Sea region, Crimea, Caucasus, and other areas of the Russian Empire.

The First World War exacerbated Russia’s anti-German and pro-Russian tendencies. During this time, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov called for a “final solution” to the ethnic German problem in Russia, noting that the time had come ". . . to deal with this long over-due problem, for the current war has created the conditions to make it possible to solve this problem once and for all.”

The Germans living in Volhynia (in the north-western part of Ukraine) were the first to suffer deportation in 1915 under the Tsar. However, the Bolsheviks, who had begun to take power in Russia, rescinded a decree the following year that would have expelled the Volga Germans.

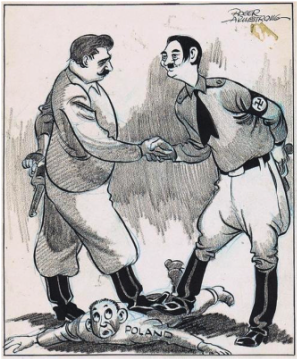

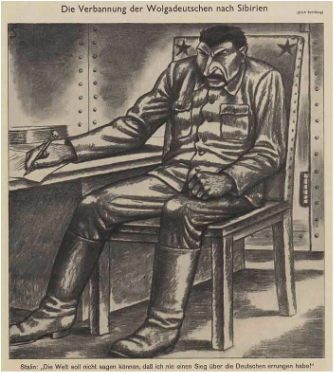

Anti-German feelings increased dramatically with Adolf Hitler’s betrayal of Josef Stalin in June of 1941. Hitler ignored the non-aggression pact he had agreed to with Stalin in 1939 and invaded the Soviet Union in what was called Operation Barbarossa.

As Hitler’s tanks rolled eastward, Stalin’s Soviet government saw the Nazi invasion as an opportunity to solve the longstanding “German problem.” Plans were hastily made to deport all ethnic Germans in the Volga region and other parts of Russia to Siberia and Kazakhstan (then part of the Soviet Union) simply because of their German heritage.

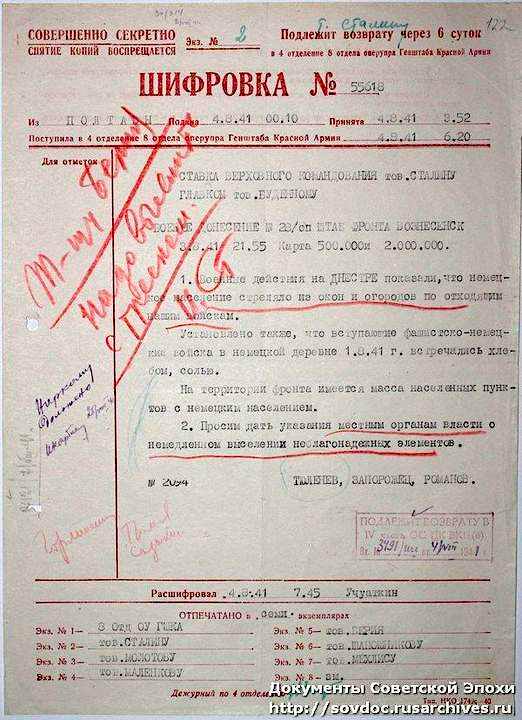

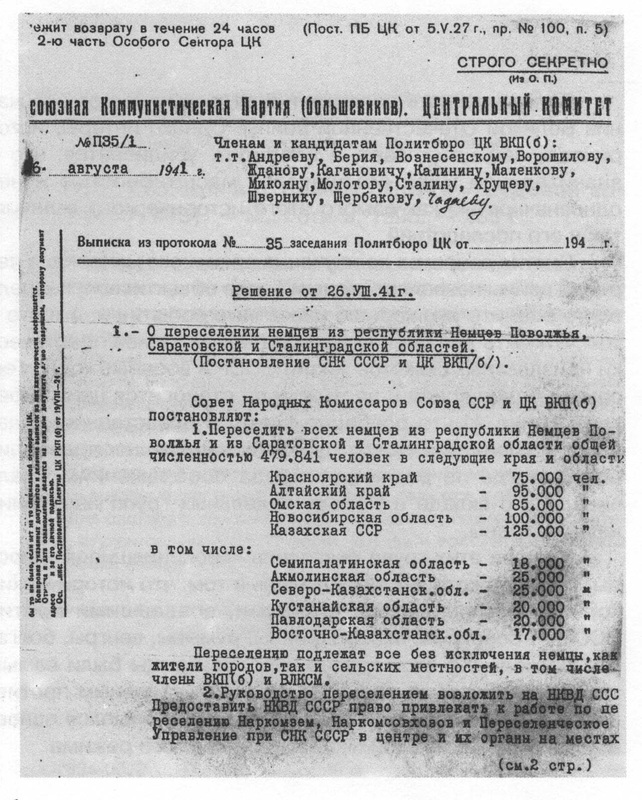

On August 26, 1941, the People's Commissars of the USSR and the Central Committee of the CPSU adopted a secret resolution on the "resettlement of all Germans from the Autonomous Republic of the Volga Germans, Stalingrad and Saratov regions to other territories and regions."

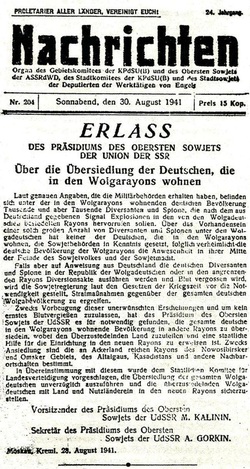

The formal decree (Ukaz no. 21-160) was signed by the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, Mikhail Kalinin, and Secretary of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, A. Gorkin, on August 28, 1941, abolishing the Volga German ASSR which had been established in 1918. Exactly 174 years after its founding in August 1767, life in the German colony of Norka and all other German colonies in the Volga region ended within weeks.

The official Soviet explanation for the mass expulsion of the ethnic Germans of the Volga and elsewhere in the USSR to special settlements is that they represented a potential fifth column of spies and saboteurs waiting to assist the invading Nazi forces. The Stalin regime justified the deportation of nearly half a million ethnic Germans from the Volga region by claiming that they actively harbored tens of thousands of spies and saboteurs loyal to the Third Reich.

Louis de Jong, a Dutch historian who extensively studied the claims of German "fifth columns," concluded that the German intelligence agencies did not rely on the assistance of the ethnic German minority living in the Soviet Union because they lived in such remote areas of Russia that establishing contact with them was impossible. He further states that there is no evidence in the German archives of a conspiracy between the ethnic Germans in Russia and the Third Reich.

It is important to note that only about 25 percent of the Volga Germans had immigrated to the United States, Canada, and South America between 1875 and the early 1920s. After the early 1920s, the Communists shut down any possibility of leaving the Soviet Union through the so-called “Iron Curtain.”

In drawing a national connection between its own ethnic Germans and the foreign invaders of Nazi Germany, the deportation decree was published on August 30th in the German language newspaper Nachrichten and the Russian language newspaper Bolshevik. Below is the critical text from his decree:

Louis de Jong, a Dutch historian who extensively studied the claims of German "fifth columns," concluded that the German intelligence agencies did not rely on the assistance of the ethnic German minority living in the Soviet Union because they lived in such remote areas of Russia that establishing contact with them was impossible. He further states that there is no evidence in the German archives of a conspiracy between the ethnic Germans in Russia and the Third Reich.

It is important to note that only about 25 percent of the Volga Germans had immigrated to the United States, Canada, and South America between 1875 and the early 1920s. After the early 1920s, the Communists shut down any possibility of leaving the Soviet Union through the so-called “Iron Curtain.”

In drawing a national connection between its own ethnic Germans and the foreign invaders of Nazi Germany, the deportation decree was published on August 30th in the German language newspaper Nachrichten and the Russian language newspaper Bolshevik. Below is the critical text from his decree:

“According to reliable facts, which were obtained by the military authorities, among the German population residing in the districts in the Volga Region, there are thousands and tens of thousands of saboteurs and spies, who, at a signal given from Germany, must commit sabotage in the districts, which are populated by the Germans in the Volga Region.

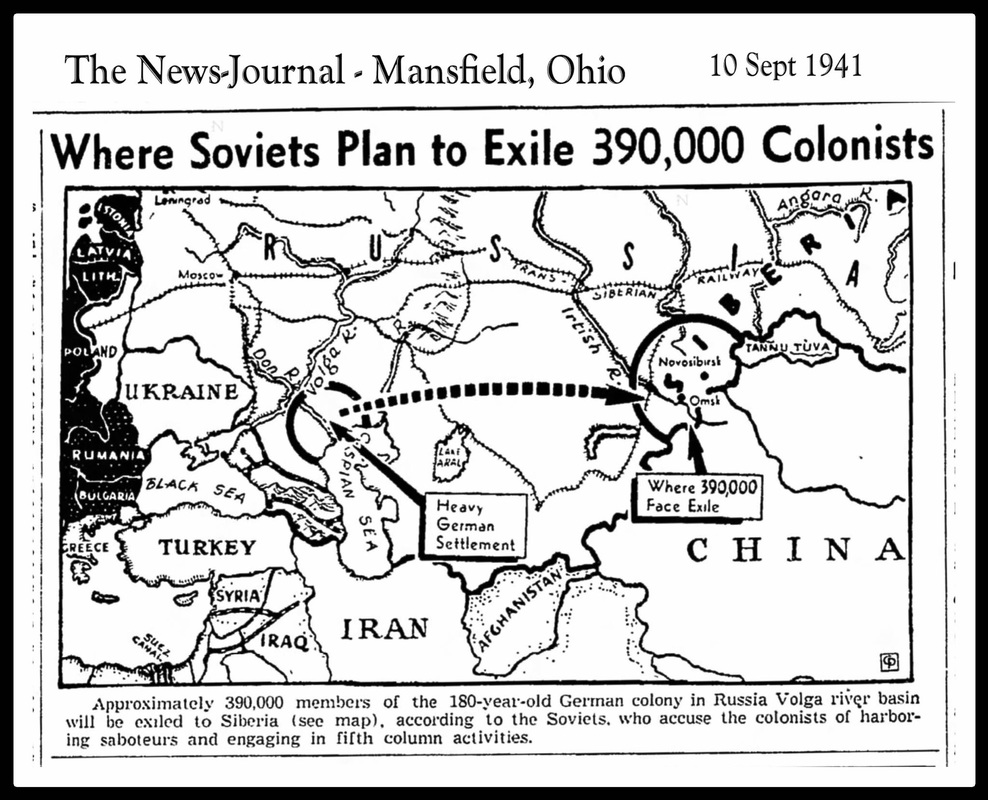

In order to avoid such undesirable occurrences and for the prevention of serious bloodshed, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR deems it necessary to resettle the entire German population residing in the districts in the Volga Region and other districts, and that the re-settlers be allotted land and receive state assistance in the new districts.

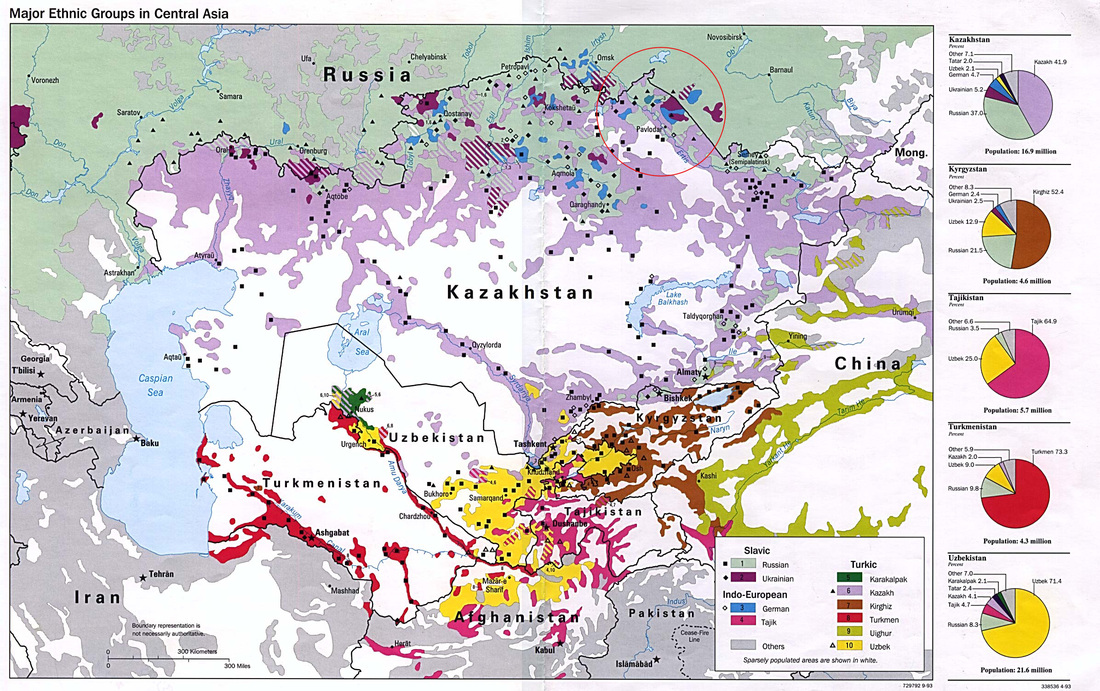

For this purpose, the abundance of arable land in the districts of Novosibirsk, the Omsk Region, the Altai Region, Kazakhstan, and other neighboring regions is to be distributed to the re-settlers.

In connection with this, the State Committee of Defense is instructed to execute urgently the removal of all Germans in the Volga.”

Stalin’s regime had no evidence to support the charge that there were thousands of potential spies and saboteurs among the Volga Germans. In the months previous to the deportations, the NKVD (Soviet secret police) had unearthed very few people suspected of political disloyalty among the Volga Germans. After the Nazi invasion of the USSR, the NKVD significantly increased its surveillance of the ethnic German population of the USSR. This was especially true in the Volga German ASSR and Saratov Oblast, where more than 400,000 Volga Germans lived. Between June 22nd and August 10th of 1941, the NKVD only arrested 145 Germans in the Volga German Republic for reasons related to state security. Out of these 145 political arrests, the NKVD accused only two of them of being German spies.

On July 13, 1941, the Volga German ASSR formed a militia of over 11,000 men in preparation for war. The same day, the Chairman of the Supreme Council of Volga German ASSR, K. Hoffman, and the Chairman of the People's Commissars of the ASSR, A. Heckman, spoke directly to the German people on the Soviet broadcasting system. In their address, they asked the German people not to shed the blood of the Soviet people and to turn their guns against Hitler and "fascist cannibals."

Tens of thousands of ethnic Germans living in Russia soon joined the fight against the Nazis during June, July, and August of 1941. From the outbreak of the war until mid-July 1941, over 2,500 Volga Germans voluntarily enlisted in the Red Army, and another 8,000 joined militia units. A story in Pravda on July 15, 1941, praised the heroic contributions of thousands of ethnic Germans to the Soviet war effort. Germans in the Red Army played an important role in the defense of Brest and other key battles in the first months after the Nazi assault upon the USSR.

Feodor Schreiber, a native of the colony of Schilling, wrote:

On July 13, 1941, the Volga German ASSR formed a militia of over 11,000 men in preparation for war. The same day, the Chairman of the Supreme Council of Volga German ASSR, K. Hoffman, and the Chairman of the People's Commissars of the ASSR, A. Heckman, spoke directly to the German people on the Soviet broadcasting system. In their address, they asked the German people not to shed the blood of the Soviet people and to turn their guns against Hitler and "fascist cannibals."

Tens of thousands of ethnic Germans living in Russia soon joined the fight against the Nazis during June, July, and August of 1941. From the outbreak of the war until mid-July 1941, over 2,500 Volga Germans voluntarily enlisted in the Red Army, and another 8,000 joined militia units. A story in Pravda on July 15, 1941, praised the heroic contributions of thousands of ethnic Germans to the Soviet war effort. Germans in the Red Army played an important role in the defense of Brest and other key battles in the first months after the Nazi assault upon the USSR.

Feodor Schreiber, a native of the colony of Schilling, wrote:

“I want to tell people one more truth about the last war. Many Germans fought against the fascists then, but these facts were always hidden. The fate of many of them is sad. The historian, General Dmitry Volkogonov, wrote in his memoirs that 200 thousand Soviet Germans were at the front during the last war, fought well, many were awarded orders, and 11 people were awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. From our native village of Schilling, in the Saratov region, 21 people fought."

Another story noting the role of ethnic Germans in the defense of the USSR appeared on August 24, 1941, in Komsomolskaya Pravda (a prominent Soviet newspaper). This article highlighted the loyalty and bravery of German soldiers in the Red Army. The focus of the article was a Komsomol member named Heinrich Hoffmann, who died under extreme torture rather than providing information to his Nazi captors. It was only after the Soviet government promulgated the order to deport the Volga Germans on August 28th that the Soviet press ceased to note the positive contributions of ethnic Germans to the anti-Nazi resistance in the USSR.

The evidence does not support claims of treasonous acts among the Soviet Union’s German minorities. Instead, the only connections between the ethnic Germans of the USSR and Nazi Germany were their shared language and culture.

The evidence does not support claims of treasonous acts among the Soviet Union’s German minorities. Instead, the only connections between the ethnic Germans of the USSR and Nazi Germany were their shared language and culture.

The deportation of the Volga Germans was not done in secret. The story was reported in many newspapers and magazines across the United States, including the New York Times and the widely-read German-Russian newspaper Die Welt-Post, on September 11, 1941.

The deportation order impacted all ethnic Germans, including officers in the Russian military and high-ranking Communist party officials, including all of the members of the Autonomous Volga German Republic, who were arrested and accused of counter-revolutionary activity and supporting a secret uprising against the Soviet powers on behalf of Nazi Germany.

Only a few German women married to non-German men were spared the deportation order. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote in his book, The Gulag Archipelago:

Only a few German women married to non-German men were spared the deportation order. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote in his book, The Gulag Archipelago:

“Then there was the wave of Germans – Germans living on the Volga, colonists in the Ukraine and North Caucasus, and all Germans in general who lived anywhere in the Soviet Union. The determining factor here was blood, and even heroes of the Civil War [the Russian Revolution] and old members of the Party who were German were sent off to exile.”

Clearly, the deportation had nothing to do with potential “spies and saboteurs” but was aimed at the German ethnic group and other ethnic groups the Soviets viewed as troublesome. These groups included the Crimean Tatars, Meskhetian Turks, Koreans, Greeks, and Kurds, who were also deported from their homelands. Of all these groups, the ethnic Germans were by far the largest.

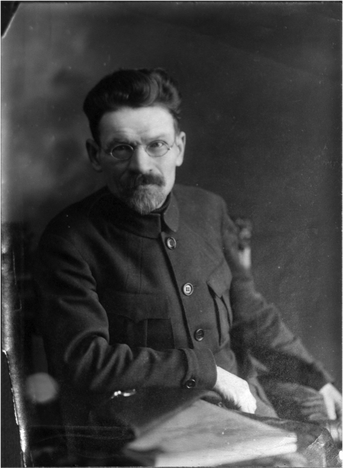

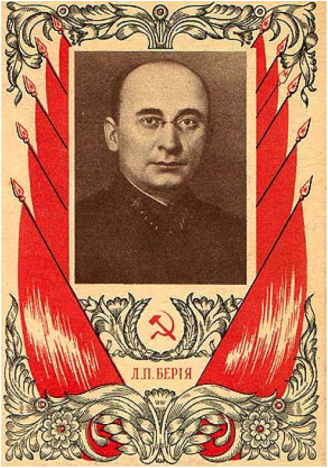

The deportation order was carried out by Lavrentiy Beria, Chief of the NKVD, who was responsible for the deaths of millions during Stalin’s Great Purge.

The deportation order was carried out by Lavrentiy Beria, Chief of the NKVD, who was responsible for the deaths of millions during Stalin’s Great Purge.

Beria charged his deputy, Ivan Alexandrovich Serov, with carrying out the operational details of the deportation he reported starting on August 29th. Serov was also responsible for the mass deportation of the Crimean Tatars, the Chechens, and people from the Baltic states. He was also responsible for the Katyn massacre in 1940.

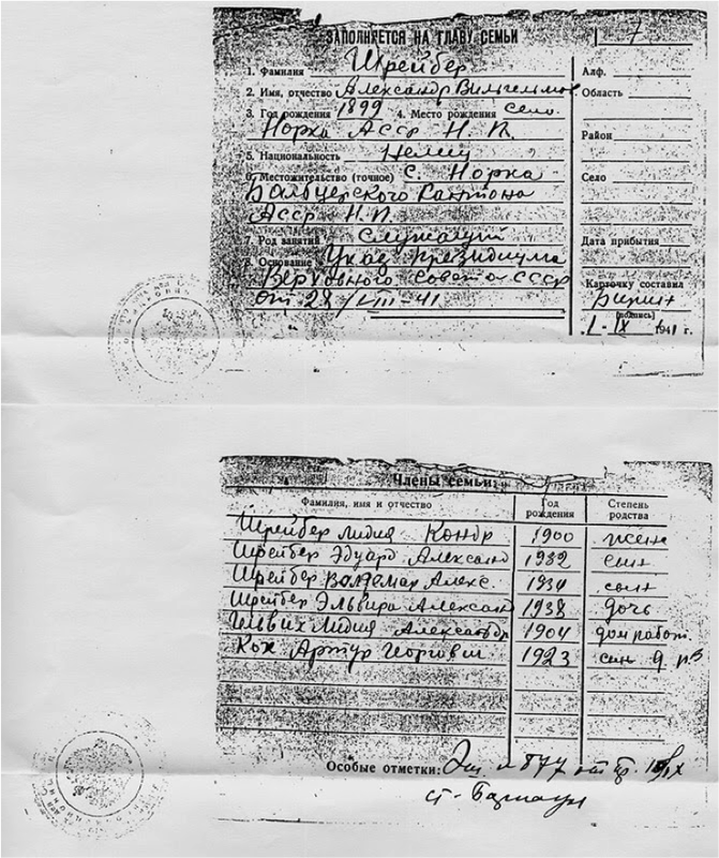

According to numerous first-hand reports, including one from Norka resident Alexander Konrad Schreiber, thousands of Russian soldiers and militia arrived in the Volga villages a few hours after the order, and the people were given as little as four hours to prepare for the evacuation. They were told that anyone resisting or attempting to hide would be summarily shot, and a few were.

They were also falsely told that the relocation was temporary and they could return home at the war's end.

They were also falsely told that the relocation was temporary and they could return home at the war's end.

The Soviets sent task forces into each colony, collective farm, and city to record each family subject to deportation on index cards.

Regardless of age, each person was allowed one suitcase or bundle (a maximum of 30 kilograms or about 66 pounds per person) with personal items and small household goods. They were promised that hot meals and bread would be provided on the trains. A promise that the Soviets were utterly unprepared to fulfill.

Many knew they would be sent to Siberia and took all the food, clothing, and bedding they could carry. In the long run, those with the extra clothing and bedding had the best chance of surviving the cold in the north, where little or no preparation had been made for their arrival.

Ironically, the Germans were given receipts for their left-behind possessions, which most people knew would never be honored.

Regardless of age, each person was allowed one suitcase or bundle (a maximum of 30 kilograms or about 66 pounds per person) with personal items and small household goods. They were promised that hot meals and bread would be provided on the trains. A promise that the Soviets were utterly unprepared to fulfill.

Many knew they would be sent to Siberia and took all the food, clothing, and bedding they could carry. In the long run, those with the extra clothing and bedding had the best chance of surviving the cold in the north, where little or no preparation had been made for their arrival.

Ironically, the Germans were given receipts for their left-behind possessions, which most people knew would never be honored.

This was a massive effort on the part of the Soviet government during the midst of World War II when resources were already stretched thin. Some 20,000 NKVD troops and vast quantities of rolling stock and other resources were diverted from the war effort to shift this enormous number of old people, women, and children to distant lands quite unprepared to receive them. The Germans were to be resettled in the Altai, Omsk, and Novosibirsk regions of Western Siberia and Kazakhstan. The deportation was to be completed by September 20, 1941. Over 3.5 million rubles were allocated to the deportation of the ethnic Germans.

The deportation of Norka began shortly after the deportation decree on August 28th. It is estimated that about 8,000 people were living in Norka when the decree was issued. The last reliable number recorded was 7,700 in 1931. If you are a descendant of Norka, you almost certainly had family members who experienced this horror.

The people of Norka, like all the ethnic Germans living in the Volga region, were forced to leave their homes, furniture, most personal items, and all of their livestock. Most would never see their homes again.

The entire population was forced to load their belongings onto wagons and trucks belonging to the local collective farms. Once loaded, they were transported to the nearest rail station at Saratov or Uvek (a suburb station of Saratov) under the armed supervision of the NKVD and the Red Army, who assured that no one deserted. It can be imagined that many of those not in good health, along with the old and very young, did not make it to the station.

The road to the train stations took the people from Norka through the neighboring Russian village of Rybushka. Despite historical tensions, most Russians surely must have had mixed emotions when they saw their long-time German neighbors being marched away, unlikely to ever be seen again.

The deportation of Norka began shortly after the deportation decree on August 28th. It is estimated that about 8,000 people were living in Norka when the decree was issued. The last reliable number recorded was 7,700 in 1931. If you are a descendant of Norka, you almost certainly had family members who experienced this horror.

The people of Norka, like all the ethnic Germans living in the Volga region, were forced to leave their homes, furniture, most personal items, and all of their livestock. Most would never see their homes again.

The entire population was forced to load their belongings onto wagons and trucks belonging to the local collective farms. Once loaded, they were transported to the nearest rail station at Saratov or Uvek (a suburb station of Saratov) under the armed supervision of the NKVD and the Red Army, who assured that no one deserted. It can be imagined that many of those not in good health, along with the old and very young, did not make it to the station.

The road to the train stations took the people from Norka through the neighboring Russian village of Rybushka. Despite historical tensions, most Russians surely must have had mixed emotions when they saw their long-time German neighbors being marched away, unlikely to ever be seen again.

One of only two Germans who remained in Norka was Elvira Zaharina, whose mother, Natalija Zaharina (née Burbach), had married a Russian man. Elvira recalls the following about the day of deportation:

"We remained the only Germans in the village. The soldiers have taken all the people away. At night, mum and I nestled to each other and cried. Cows lowed, dogs barked, cats mewed...all of the village was without people... "

By September 5th, the deportees were arriving at the Saratov station and loading into freight and cattle cars crowded with 50 or 60 people. Some of the cars had open vents, and some had no vents at all.

Lists were made of deported families as they arrived at the railheads. In addition to the family members, the lists show the date and point of departure.

Lists were made of deported families as they arrived at the railheads. In addition to the family members, the lists show the date and point of departure.

188 train convoys (echelons) departed from 31 stations, transporting 451,986 people from their homes. By comparison, the U.S. government wrongly interned about 110,000 Japanese during World War II.

Echelon 877 transported many of the people from Norka to an unknown future. This group of 2,386 people departed from the Uvek station on September 10, 1941, one of the later groups to be sent eastward.

Echelon 877 transported many of the people from Norka to an unknown future. This group of 2,386 people departed from the Uvek station on September 10, 1941, one of the later groups to be sent eastward.

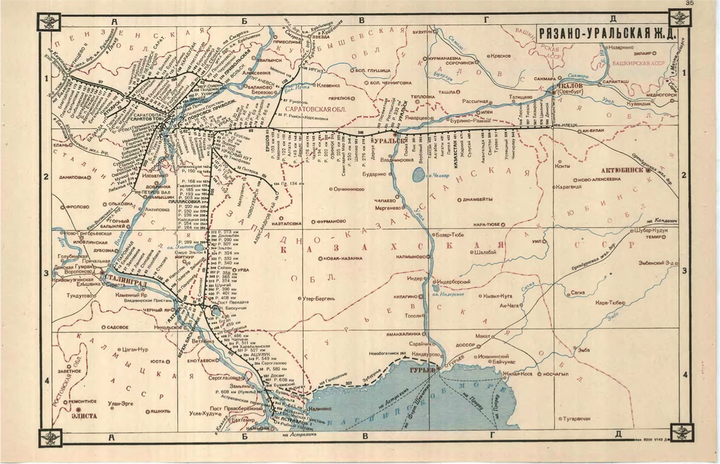

The long and arduous journey to Kazakhstan and Siberia started as the trains crossed the railroad bridge over the Volga River at Uvek. Ironically, the truss bridge had been built only a few years prior and was completed on May 17, 1935.

After crossing the Volga at Uvek, the trains proceeded east. Some deportation trains took a northern route from Uralsk to Omsk and further into Siberia. Most of the people from Norka took a route that dipped deep into Kazakhstan and then turned north into the Altai region of Siberia. This was a much longer route.

The journey through the desert lands of Kazakhstan must have been very difficult, with virtually no protection from the hot sun during the day and cold nights.

According to Alexander Konrad Schreiber from Norka, his transport train (Echelon 877) was en route for about two weeks. The trains with the deportees were often forced to wait on rail sidings to make way for military transports traveling west to the front lines.

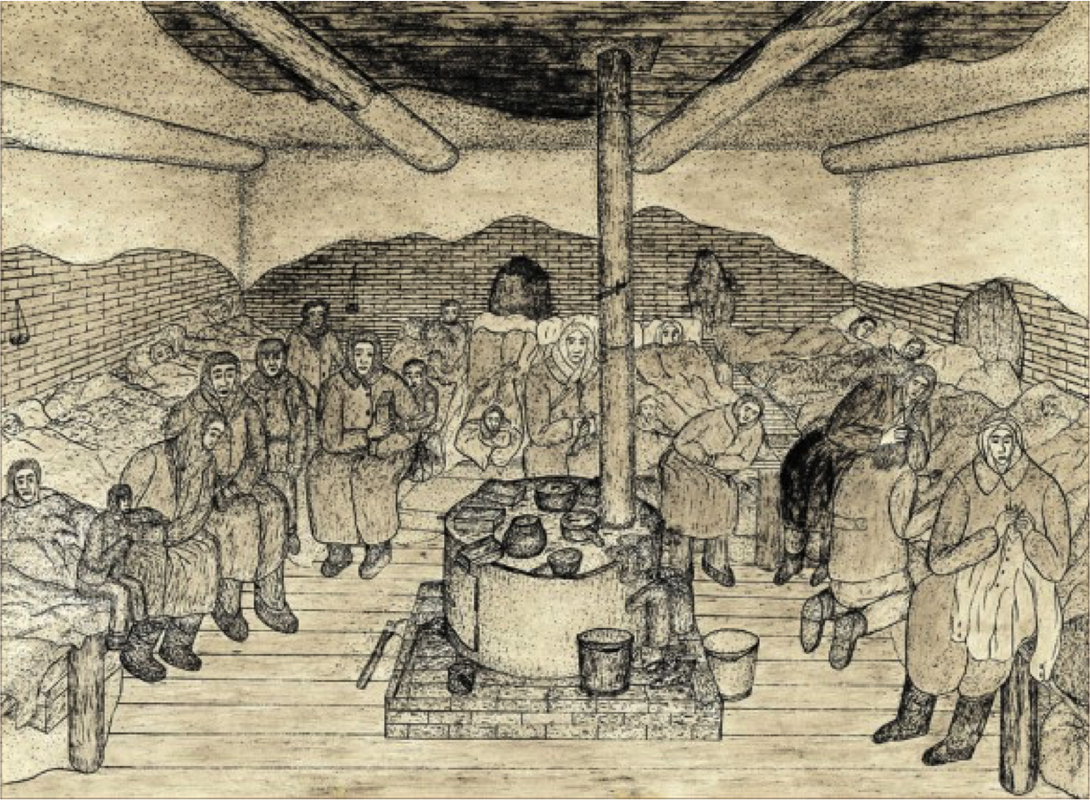

The deportees had to rely primarily on the food they brought, and they were only given water when the train stopped every three or four days. When food was provided, it was generally salted herring, which only increased the prisoners' thirst.

Unsanitary conditions in the rail cars were compounded by the poor quality of available water. These conditions led to outbreaks of infectious diseases such as dysentery. Many died, and the victims were primarily children and the elderly.

The consequences for the Volga Germans were devastating. Tens of thousands are believed to have died during the journey to Siberia, which lasted up to two months. In some cases, bodies were left in the overcrowded cattle wagons for weeks on end. In others, they were thrown out beside the tracks.

According to Alexander Konrad Schreiber from Norka, his transport train (Echelon 877) was en route for about two weeks. The trains with the deportees were often forced to wait on rail sidings to make way for military transports traveling west to the front lines.

The deportees had to rely primarily on the food they brought, and they were only given water when the train stopped every three or four days. When food was provided, it was generally salted herring, which only increased the prisoners' thirst.

Unsanitary conditions in the rail cars were compounded by the poor quality of available water. These conditions led to outbreaks of infectious diseases such as dysentery. Many died, and the victims were primarily children and the elderly.

The consequences for the Volga Germans were devastating. Tens of thousands are believed to have died during the journey to Siberia, which lasted up to two months. In some cases, bodies were left in the overcrowded cattle wagons for weeks on end. In others, they were thrown out beside the tracks.

Below is a map of the deportation route taken by the people living in Norka in 1941. Alexander Schreiber (the son of Alexander Konrad Schreiber) provided the details of this route.

Russian records show that the people from Norka who were part of Echelon 877 were unloaded at the train station in Kulunda on September 15, 1941. Kulunda is located in the Altai region of Siberia. From there, trucks took them to the Russian villages of Gilevka, Gonokhovo, and Zav'yalovo. Generally, the German deportees were not allowed to live in cities; they were only allowed to live in small rural villages.

It was late September, and the first signs of winter were already creeping over the landscape, where temperatures can drop to minus 45 degrees Fahrenheit. While some of the Russians living in this area were kind to the German deportees, many called their new neighbors “fascists” and worse. The Soviet government did nothing to explain that the Volga Germans were not responsible for the actions of the Nazis. This lack of information increased the hostility from those living in the resettlement areas.

The Soviet authorities had little time to prepare for the arrival of such large numbers of people, and there was great confusion and a lack of organization.

In the Novosibirsk region, approximately 45 percent of those deported were listed as children, and about 6 percent were classified as elderly.

Although still Soviet citizens, the ethnic Germans were stripped of their civil rights and permanently restricted to living in “special settlements.” They remained in this status until 1955, when they were finally allowed to seek permission to relocate to other parts of Siberia and Kazakhstan.

The Soviet authorities had little time to prepare for the arrival of such large numbers of people, and there was great confusion and a lack of organization.

In the Novosibirsk region, approximately 45 percent of those deported were listed as children, and about 6 percent were classified as elderly.

Although still Soviet citizens, the ethnic Germans were stripped of their civil rights and permanently restricted to living in “special settlements.” They remained in this status until 1955, when they were finally allowed to seek permission to relocate to other parts of Siberia and Kazakhstan.

The lack of proper housing proved a significant problem for the deportees. By January 1942, German exiles had already exhausted the local housing. In the Altai region, for instance, the local NKVD authorities reported in October 1941 that they could house 100,000 German special settlers. By January 1942, however, over 110,000 German exiles had already arrived. The buildings that did exist often had no roofs or windows. Frequently, the exiles had to construct crude shelters out of earth and straw for protection from the elements. In Altai, as late as 1950, 46 percent of the German special settlers still lived in these primitive huts. The extremely harsh conditions of the special settlements contributed to a significant increase in mortality among the Russian Germans during the 1940s.

Within the first year, most of the men who were deported were separated from their families and sent to Gulags or labor camps, where they worked in primitive conditions and severe weather. The deportees were systematically faced with repression in many forms.

On July 2, 1942, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic renamed the village of Norka and the surrounding district to Nekrasovo.

On July 2, 1942, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic renamed the village of Norka and the surrounding district to Nekrasovo.

Sources

Bauer, Susan Wise. The History of the Ancient World. Chapter 51.

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Conquest, Robert. The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities. London: Macmillan, 1970. Print.

"Deportation of the German Population from the European Part of the USSR to Western Siberia (1941-1945 Biennium) (Russian Language)." Мемориал - Главная страница. N.p., Aug. 2015. Web. <http://old.memo.ru/history/nem/Chapter14.htm>. The 1775 and 1798 Censuses of the German Colony on the Volga, Norka: Also Known as Weigand. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1995. Print.

German, A. "Vyselit' s treskom". Ochevidtsy i issledovateli o tragedii rossiiskikh nemtsev ("Fortjagen muss man sie". Zeitzeugen und Forscher berichten uber die Tragodie der Russlanddeutschen). Ed. O. Silantjewa. Moscow: MSNK-Press, 2011.

German, A. История республики немцев Поволжья в событиях, фактах, документах. М., 1996. С. 238-240.

German, A.A. ДЕПОРТАЦИЯ СОВЕТСКИХ НЕМЦЕВ ИЗ ЕВРОПЕЙСКОЙ ЧАСТИ СССР ОСЕНЬЮ 1941 г., 2011.

Grib, EA Commemorative book: Usol'laga NKVD-MVD SSSR, 1942-1947 (A memorial book of the Germans in Labor Army Usollag NKVD / MVD the USSR 1942-1947). Ed. VF Dizendorf: Public Academy of Sciences of the Russian Germans, 2006. Print.

Jong, Louis de, and C. M. Geyl. The German Fifth Column in the Second World War. London: Routledge & Paul, 1956. Print.

Pohl, J. Otto. "The Deportation and Destruction of the German Minority in the USSR." JOP (2004): Print.

Pohl, J. Otto. Works Dealing with the Deportation of the Volga Germans on 28 August 1941. Website. August 2016.

Krieger, Viktor. "Patriots or Traitors? - The Soviet Government and the 'German Russians' After the Attack on the USSR by National Socialist Germany." Trans. Catherine Venner. Russian-German Special Relations in the Twentieth Century: A Closed Chapter? Comp. Karl Schlögel. Oxford: Berg, 2006. 133-63. Print.

Krieger, Viktor. Bundesbuerger russlanddeutscher Herkunft: Historische Schluesselerfahrungen und kollektives Gedaechtnis. Muenster: Lit Verlag, 2013, table no. 1, p. 30.

Schrieber, Alexander, Moscow, Russia and Urbach, Konrad, Albstadt, Germany. Konrad lived in Norka prior to the deportation.

Schwabenland Haynes, Emma. "The Deportation of the Soviet Germans." Work Paper of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia #24 (1977): 5-18. Print.

Sinner, Samuel D. The Open Wound: The Genocide of German Ethnic Minorities in Russia and the Soviet Union, 1915-1949 and beyond. Fargo, ND: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State University Libraries, 2000. Print.

Shpak, Alexander. Deportation of the Volga Germans in the year 1941. http://wolgadeutsche.net/deportation. Viewed on 19 May 2019.

Diary of the Deportation in 1941 by Konrad Weidenkeller (Volk auf dem Weg Nr. 8-9/2021)

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Conquest, Robert. The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities. London: Macmillan, 1970. Print.

"Deportation of the German Population from the European Part of the USSR to Western Siberia (1941-1945 Biennium) (Russian Language)." Мемориал - Главная страница. N.p., Aug. 2015. Web. <http://old.memo.ru/history/nem/Chapter14.htm>. The 1775 and 1798 Censuses of the German Colony on the Volga, Norka: Also Known as Weigand. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1995. Print.

German, A. "Vyselit' s treskom". Ochevidtsy i issledovateli o tragedii rossiiskikh nemtsev ("Fortjagen muss man sie". Zeitzeugen und Forscher berichten uber die Tragodie der Russlanddeutschen). Ed. O. Silantjewa. Moscow: MSNK-Press, 2011.

German, A. История республики немцев Поволжья в событиях, фактах, документах. М., 1996. С. 238-240.

German, A.A. ДЕПОРТАЦИЯ СОВЕТСКИХ НЕМЦЕВ ИЗ ЕВРОПЕЙСКОЙ ЧАСТИ СССР ОСЕНЬЮ 1941 г., 2011.

Grib, EA Commemorative book: Usol'laga NKVD-MVD SSSR, 1942-1947 (A memorial book of the Germans in Labor Army Usollag NKVD / MVD the USSR 1942-1947). Ed. VF Dizendorf: Public Academy of Sciences of the Russian Germans, 2006. Print.

Jong, Louis de, and C. M. Geyl. The German Fifth Column in the Second World War. London: Routledge & Paul, 1956. Print.

Pohl, J. Otto. "The Deportation and Destruction of the German Minority in the USSR." JOP (2004): Print.

Pohl, J. Otto. Works Dealing with the Deportation of the Volga Germans on 28 August 1941. Website. August 2016.

Krieger, Viktor. "Patriots or Traitors? - The Soviet Government and the 'German Russians' After the Attack on the USSR by National Socialist Germany." Trans. Catherine Venner. Russian-German Special Relations in the Twentieth Century: A Closed Chapter? Comp. Karl Schlögel. Oxford: Berg, 2006. 133-63. Print.

Krieger, Viktor. Bundesbuerger russlanddeutscher Herkunft: Historische Schluesselerfahrungen und kollektives Gedaechtnis. Muenster: Lit Verlag, 2013, table no. 1, p. 30.

Schrieber, Alexander, Moscow, Russia and Urbach, Konrad, Albstadt, Germany. Konrad lived in Norka prior to the deportation.

Schwabenland Haynes, Emma. "The Deportation of the Soviet Germans." Work Paper of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia #24 (1977): 5-18. Print.

Sinner, Samuel D. The Open Wound: The Genocide of German Ethnic Minorities in Russia and the Soviet Union, 1915-1949 and beyond. Fargo, ND: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State University Libraries, 2000. Print.

Shpak, Alexander. Deportation of the Volga Germans in the year 1941. http://wolgadeutsche.net/deportation. Viewed on 19 May 2019.

Diary of the Deportation in 1941 by Konrad Weidenkeller (Volk auf dem Weg Nr. 8-9/2021)

Last updated December 7, 2023

Copyright © 2002-2024 Steven H. Schreiber

- Home

- People

- Community

-

History

- Timeline

- Origins of the Colonists

- Catherine's Manifesto 1763

- Why go to Russia?

- Recruitment 1766

- Planning 1764-1766

- Marriages Prior To Emigration 1766

- Voyage to Russia 1766 >

- Journey 1766-1767

- Founding of Norka 1767

- Early Years 1767-1769

- Norka 1769

- Pallas Report 1773

- Pugachev Raid 1774

- Norka 1775

- Norka 1798

- Norka 1811

- Napoleons Soldiers

- Norka 1834

- Daughter Colonies 1850s >

- Privileges Lost 1871-1874

-

Immigration 1875-1924

>

- Famine 1891-1892

- Norka 1898

- War & Turnoil 1904-1906

- World War 1914-1918

- Revolution & War 1917-1922

- Soviet Rule 1918-1941

- Famine 1921-1924

- Famine 1932-1933

- The Great Terror 1936-1938

- Deportation 1941

- Repression 1941-1956

- Cultural Loss 1957-2006

- A Culture in Peril

- Recent Times

- Traditions

-

Religion

- Resources