History > Immigration to America Begins

Immigration to America Begins - 1874

Based on research from Russian archival documents, Dr. Igor Pleve states that the conditions that led to Volga German emigration from 1874 to the mid-1880s differed from those during the mid-1880s until World War I.

"The German is like a willow. No matter which way you bend him, he will always take root again." - Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Changing Conditions 1871-1874

On June 4, 1871, a decree by Tsar Alexander II caused the Volga Germans to begin considering emigration from Russia.

Under Alexander II's reforms, many of the special privileges granted to the Volga Germans by Catherine II's Manifesto were abolished, and their government protector, the Kontora, was discontinued. From that point forward, the Volga Germans had the same status and were subject to the same bureaucratic provincial administration imposed on the Russian peasants freed from serfdom. The Russian provincial officials became less supportive of the colonists and sometimes exhibited xenophobic hostility towards them. All communications with the government were now required to be in the Russian language, in which few Germans were fluent.

The Russian government wanted the Germans to assimilate to create a more integrated state through a shared identity with other ethnic groups. While this may have been a reasonable goal, there was no outreach to the Germans explaining the reasons for the sweeping changes. Rumors and speculation soon filled the void. Many felt that the strong push to Russify the ethnic Germans threatened their cultural identity through a loss of language, culture, and religion.

Concurrent with Alexander II's reforms, a law was passed in 1871, giving the Volga Germans a ten-year window to emigrate to America or other countries. Before this time, no one in the Russian Empire had the right to leave without permission from the government. Despite the new opportunity to emigrate, few seriously considered it until 1874.

In 1874, the perpetual exemption from military service promised in the Manifesto was stripped from the colonists. For the majority of Volga Germans, military conscription created anxiety and served as a potential trigger for emigration. However, most accepted this new requirement. It is not uncommon to see photographs of Volga German men in military uniforms.

Compulsive military service was most alarming to small groups of Protestant Volga Germans who had broken away from the Lutheran Church (which now included those of the Reformed faith). In particular, Mennonites, Baptists, and members of the Brüderschaft (Brethren Movement) were among the first to consider leaving Russia due to the inherent conflict between military service and their religious beliefs.

This verse from the Auswandererlied (Emigrants song) reflects their feelings at the time:

Under Alexander II's reforms, many of the special privileges granted to the Volga Germans by Catherine II's Manifesto were abolished, and their government protector, the Kontora, was discontinued. From that point forward, the Volga Germans had the same status and were subject to the same bureaucratic provincial administration imposed on the Russian peasants freed from serfdom. The Russian provincial officials became less supportive of the colonists and sometimes exhibited xenophobic hostility towards them. All communications with the government were now required to be in the Russian language, in which few Germans were fluent.

The Russian government wanted the Germans to assimilate to create a more integrated state through a shared identity with other ethnic groups. While this may have been a reasonable goal, there was no outreach to the Germans explaining the reasons for the sweeping changes. Rumors and speculation soon filled the void. Many felt that the strong push to Russify the ethnic Germans threatened their cultural identity through a loss of language, culture, and religion.

Concurrent with Alexander II's reforms, a law was passed in 1871, giving the Volga Germans a ten-year window to emigrate to America or other countries. Before this time, no one in the Russian Empire had the right to leave without permission from the government. Despite the new opportunity to emigrate, few seriously considered it until 1874.

In 1874, the perpetual exemption from military service promised in the Manifesto was stripped from the colonists. For the majority of Volga Germans, military conscription created anxiety and served as a potential trigger for emigration. However, most accepted this new requirement. It is not uncommon to see photographs of Volga German men in military uniforms.

Compulsive military service was most alarming to small groups of Protestant Volga Germans who had broken away from the Lutheran Church (which now included those of the Reformed faith). In particular, Mennonites, Baptists, and members of the Brüderschaft (Brethren Movement) were among the first to consider leaving Russia due to the inherent conflict between military service and their religious beliefs.

This verse from the Auswandererlied (Emigrants song) reflects their feelings at the time:

Hier in Russland ist nicht zu leben,

Weil wir müssen Soldaten geben,

Und als Ratnik müssen wir stehen -

Drum wollen wir aus Russland gehen.

Here in Russia it's no good to live,

We must our men as soldiers give,

And now as soldiers we must stand,

That's why we leave the Russian land.

"Auswandererlied," verse 1

The Role of Rev. Stärkel

Rev. Wilhelm Stärkel from Norka was a key proponent of emigration. According to Richard Sallet, Rev. Stärkel was the first Volga German to come to the United States. He served parishes in Wisconsin beginning in late 1864 and continuing until his return to Russia in April 1868. Rev. Stärkel was sympathetic towards members of the Brethren Movement who felt persecuted by some church authorities. Stärkel worked to keep the Brethren connected to the mainstream church but also understood that emigration was a good option for them.

Rev. Stärkel often spoke about America and emphasized that he would greatly prefer going to America to farm rather than staying in Russia as a soldier. Many people in Norka turned to Rev. Stärkel for information about America, and he quickly explained the advantages to them. Rev. Stärkel knew that good farmland was available, and he understood the benefits of the Homestead Act, which Abraham Lincoln signed into law on May 20, 1862.

Scouts to America

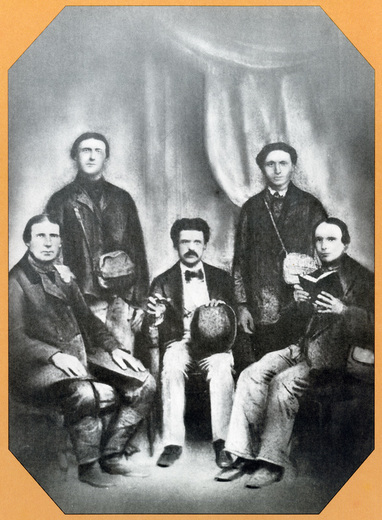

In the spring of 1874, little more than 100 years had passed since the first settlements were established on the Volga. A growing number of colonists felt that their future was not in Russia and decided to take action. Groups of Catholic colonists met at the colony of Herzog on the Wiesenseite (plains side of the Volga River) to discuss the possibility of emigration, and five delegates were elected to visit America to look for suitable places for resettlement. A similar meeting was held by Protestant colonists on the Bergseite (hilly side of the Volga River) in the colony of Balzer, resulting in the selection of an additional nine scouts.

The five scouts from the Wiesenseite included Nicholas Schamne from the colony of Graf, Peter Leiker of Obermonjou, Peter Stoecklein of Zug, Jacob Ritter of Luzern, and Anton Wasinger from Schönchen.

The five scouts from the Wiesenseite included Nicholas Schamne from the colony of Graf, Peter Leiker of Obermonjou, Peter Stoecklein of Zug, Jacob Ritter of Luzern, and Anton Wasinger from Schönchen.

The nine Bergseite scouts were Anton Kaeberlein of Pfeifer, Christoph Meisinger of Messer, Georg Stieben of Dietel, Johannes Krieger and Johannes Nolde of Norka, Georg Kähm and Heinrich Schwabauer of Balzer, Franz Scheibel and Johann Benzel of Kolb. The group included farmers, a cloth dyer, and a school teacher.

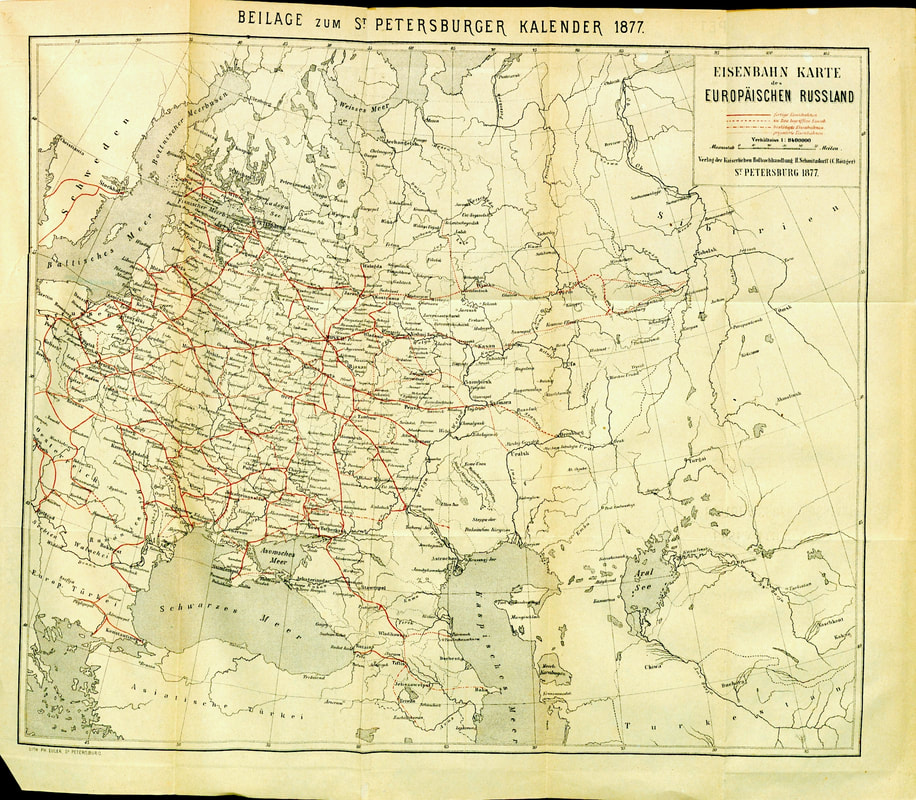

Their journey to America was greatly aided by the completion of the first rail line from Saratov to Moscow and the Baltic seaports in 1871.

Their journey to America was greatly aided by the completion of the first rail line from Saratov to Moscow and the Baltic seaports in 1871.

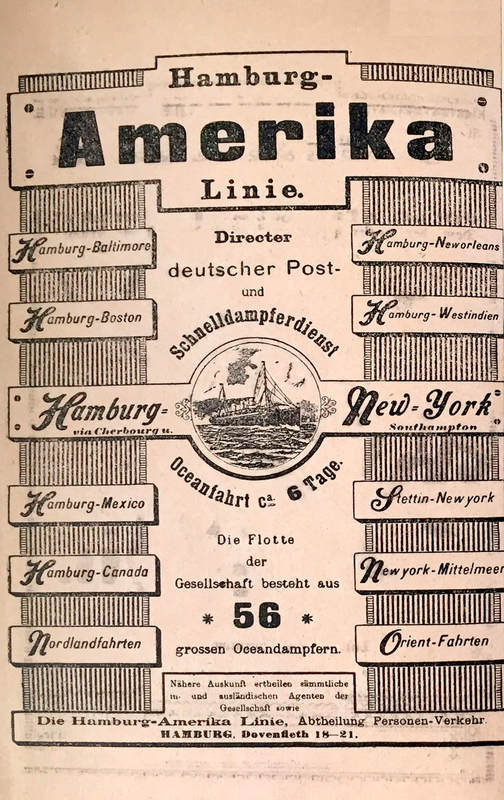

The fourteen scouts traveled together, departing on the steamship Schiller, owned by the German Transatlantic Steam Navigation Line. The Schiller departed from Hamburg, Germany, and arrived in New York on July 15, 1874. Upon disembarking at Castle Garden, they met with officials from the German Lutheran Immigrant Mission stationed there. The mission took great interest in the scouting party and later recommended they travel to Kansas City to look for land. The scouts first went to Ohio and Iowa, where they visited friends.

The scouts' time in New York was not completely pleasant. Arriving in summer, they wore heavy Russian boots, caps, and sheepskin coats. Stories were told of New Yorkers who followed them along the streets with shouts of laughter and attempts to grab their coats. Rumors also spread in the colonies that the New Yorkers had thrown rocks at the curious-looking scouts.

Upon returning to Russia, the reports from the scouts were mixed. The farmers were the least enthusiastic because the soil they had seen was sandy, and the countryside was largely unpopulated. Their lack of English language skills prevented them from meeting with government officials. The schoolteacher saw great promise in America and strongly advised emigration.

On their American journey, the scouts met an agent of a transatlantic steamship company who later wrote them "an alluring letter in the English language encouraging emigration." The letter was translated into German by Prof. Ascher of Heidelberg University, residing in the colonies, to write a history of the Volga Germans. Copies of the German translation were distributed throughout the colonies. Unfortunately, Prof. Ascher was accused by Russian authorities of being "a secret agent in the service of American companies who would ruin the colonists through the enticement of emigration," and he was driven out of the country.

In 1875, the Burlington and Missouri Railroad sent Rev. Robert Neumann, head of the Immigrant Mission at Castle Garden, to Russia to visit the Protestant Volga German colonies. Rev. Neumann preached and covertly held meetings in people's homes to encourage emigration to Nebraska. Russian officials decided to arrest Rev. Neumann, and he reportedly escaped the area hidden in a load of hay.

The reports from the resident scouts and encouragement from the steamship company, Rev. Neumann, and Pastor Stärkel strongly influenced the people of Norka. Historian Hattie Plum Williams provides the following information:

Upon returning to Russia, the reports from the scouts were mixed. The farmers were the least enthusiastic because the soil they had seen was sandy, and the countryside was largely unpopulated. Their lack of English language skills prevented them from meeting with government officials. The schoolteacher saw great promise in America and strongly advised emigration.

On their American journey, the scouts met an agent of a transatlantic steamship company who later wrote them "an alluring letter in the English language encouraging emigration." The letter was translated into German by Prof. Ascher of Heidelberg University, residing in the colonies, to write a history of the Volga Germans. Copies of the German translation were distributed throughout the colonies. Unfortunately, Prof. Ascher was accused by Russian authorities of being "a secret agent in the service of American companies who would ruin the colonists through the enticement of emigration," and he was driven out of the country.

In 1875, the Burlington and Missouri Railroad sent Rev. Robert Neumann, head of the Immigrant Mission at Castle Garden, to Russia to visit the Protestant Volga German colonies. Rev. Neumann preached and covertly held meetings in people's homes to encourage emigration to Nebraska. Russian officials decided to arrest Rev. Neumann, and he reportedly escaped the area hidden in a load of hay.

The reports from the resident scouts and encouragement from the steamship company, Rev. Neumann, and Pastor Stärkel strongly influenced the people of Norka. Historian Hattie Plum Williams provides the following information:

Among the scouting party sent to the United States by the Colonies in 1874, to seek land, were two men from Norka: Johannes Krieger and Johannes Nolde. Their reports on return soon set in motion emigration which started as early as 1875, with seven Norka families and two single men who came to Ohio and two years later went to Sutton, Nebraska. In 1876, one the largest Protestant groups of colonists ever to emigrate, was a group of eighty-five families, most of them from Norka.

Migration to America Begins in 1875

The first group of Volga German immigrants arrived in New York on June 28, 1875, aboard the steamship City of Brussels, which departed from Liverpool, England. At least five of the seven families were from Norka.

In the winter of 1875-1876, representatives of the Norddeutscher Lloyd (North German Lloyd) from Bremen and the German Transatlantic Steam Navigation Line from Hamburg visited Norka to offer their services to those who could afford the journey. The major impediment for most people was simply a lack of funds. Unlike the Black Sea Germans, Volga Germans did not own farmland. Only their house and personal property could be sold.

Igor Pleve states that of the 400 people who emigrated in 1874-75, 89 were from Norka. A relatively small percentage of Volga Germans emigrated in the first wave between 1875 and the mid-1880s, but many more would follow.

Emigration declined drastically in 1879. Increasingly concerned about the negative impacts of emigration, Russian officials sought to stem the flow of Germans. Hundreds of Volga Germans returned home after failed attempts to establish colonies in Brazil. Letters from some of these colonists were placed in public places to warn of the perils of settlement in foreign countries. People in Norka were reportedly distrustful of these letters and placed more reliance on the word of the scouts and letters from early immigrants whom they knew and trusted.

Russian officials also considered a proposal allowing Germans to own the land individually rather than communally. This idea was dropped when surveys showed scant interest.

In the winter of 1875-1876, representatives of the Norddeutscher Lloyd (North German Lloyd) from Bremen and the German Transatlantic Steam Navigation Line from Hamburg visited Norka to offer their services to those who could afford the journey. The major impediment for most people was simply a lack of funds. Unlike the Black Sea Germans, Volga Germans did not own farmland. Only their house and personal property could be sold.

Igor Pleve states that of the 400 people who emigrated in 1874-75, 89 were from Norka. A relatively small percentage of Volga Germans emigrated in the first wave between 1875 and the mid-1880s, but many more would follow.

Emigration declined drastically in 1879. Increasingly concerned about the negative impacts of emigration, Russian officials sought to stem the flow of Germans. Hundreds of Volga Germans returned home after failed attempts to establish colonies in Brazil. Letters from some of these colonists were placed in public places to warn of the perils of settlement in foreign countries. People in Norka were reportedly distrustful of these letters and placed more reliance on the word of the scouts and letters from early immigrants whom they knew and trusted.

Russian officials also considered a proposal allowing Germans to own the land individually rather than communally. This idea was dropped when surveys showed scant interest.

Changing Conditions from the mid-1880's

New waves of emigration began in 1886 and continued until the outbreak of World War I. These emigrants were driven primarily by economic reasons, including a growing population constrained by a shortage of land, poor harvests, and a famine in 1891-92. They were also drawn to America by encouraging letters from family and friends who frequently offered their financial support for transportation.

Beginning with the fourteen scouts in 1874, German migration from Russia eventually reached massive proportions. By 1920, 303,532 first and second-generation German Russians resided in the United States alone.

Beginning with the fourteen scouts in 1874, German migration from Russia eventually reached massive proportions. By 1920, 303,532 first and second-generation German Russians resided in the United States alone.

Dr. Igor Pleve estimates that about 100,000 Volga Germans migrated to the Americas. The Volga Germans' exodus stopped at the outbreak of World War I. The following Russian Revolution and Civil War continued to trap people in Russia. A handful of Volga Germans (including Norka's Conrad Brill) fled Russia during the famine of the early 1920s, with some reaching refugee camps in Germany. Under the oppressive rule of Joseph Stalin, it was nearly impossible to escape the Iron Curtain.

Leaving Home

Leaving one's ancestral village for America was often viewed by those departing and those remaining as an act of separation that would last forever. Nearly as final as death itself.

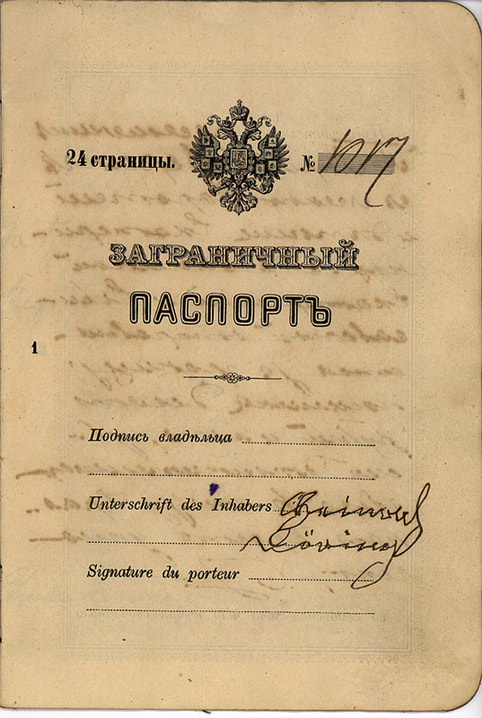

An application for permission to leave the colony must first be obtained from the village Gemeinde (council). If approved, the council provided an authorization stating the applicant owed no taxes or other debts. This authorization was necessary to apply for a passport from the Russian government in Saratov. Either a short-term or long-term passport could be obtained. Most people chose the short-term passport, knowing it was less expensive and returning to Russia was unlikely. The process took about two months.

When all the legal permissions were obtained, household possessions such as treasured feather ticks, bedding, pillows, sheepskin coats, dishes, blankets, and much more were sold to raise a few rubles for the journey. As the departure date grew closer, the emigrants took their last Communion rites and received blessings from the pastor, who provided them with a Parochialschein as an introduction to their new church in America. On the departure date, a small wagon driven by a friend or relative drew alongside the entry gate to the house, and those departing clambered aboard with their luggage. Final farewells were said to the paternal family and friends who gathered. Sometimes, farewell songs were sung. Even hardened men sobbed. From the patriarchal home, the emigrants were taken to the wife's parents to repeat the traumatic farewell scene. Finally, the heartbreaking moment arrived when the wagon pulled out of the village and out of sight along the single dirt track road leading to Saratov. Most would never return again.

The Volga Russians were different from earlier German immigrants. Their speech was laced with Russianisms, and German-Americans considered their dialects archaic. Along with their English-speaking neighbors, German-Americans referred to them as Russians and to their settlements as Russian towns. They were at the bottom of the social ladder and performed jobs that others avoided. Women were domestics; men worked as laborers, on railroad construction, or farmed. All who encountered them, however, admired their ability to work.

Like willows, the people from Norka were taking root in new lands. Soon, they would become part of settlements in the United States, Canada, and South America.

An application for permission to leave the colony must first be obtained from the village Gemeinde (council). If approved, the council provided an authorization stating the applicant owed no taxes or other debts. This authorization was necessary to apply for a passport from the Russian government in Saratov. Either a short-term or long-term passport could be obtained. Most people chose the short-term passport, knowing it was less expensive and returning to Russia was unlikely. The process took about two months.

When all the legal permissions were obtained, household possessions such as treasured feather ticks, bedding, pillows, sheepskin coats, dishes, blankets, and much more were sold to raise a few rubles for the journey. As the departure date grew closer, the emigrants took their last Communion rites and received blessings from the pastor, who provided them with a Parochialschein as an introduction to their new church in America. On the departure date, a small wagon driven by a friend or relative drew alongside the entry gate to the house, and those departing clambered aboard with their luggage. Final farewells were said to the paternal family and friends who gathered. Sometimes, farewell songs were sung. Even hardened men sobbed. From the patriarchal home, the emigrants were taken to the wife's parents to repeat the traumatic farewell scene. Finally, the heartbreaking moment arrived when the wagon pulled out of the village and out of sight along the single dirt track road leading to Saratov. Most would never return again.

The Volga Russians were different from earlier German immigrants. Their speech was laced with Russianisms, and German-Americans considered their dialects archaic. Along with their English-speaking neighbors, German-Americans referred to them as Russians and to their settlements as Russian towns. They were at the bottom of the social ladder and performed jobs that others avoided. Women were domestics; men worked as laborers, on railroad construction, or farmed. All who encountered them, however, admired their ability to work.

Like willows, the people from Norka were taking root in new lands. Soon, they would become part of settlements in the United States, Canada, and South America.

Sources

Haynes, Emma S. "Passenger List." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (Spring 1979): 68. Print.

Hoelzer, John. "The Earliest Volga Germans in Sutton, Nebraska and Portion of Their History." Work Paper #16 of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (December 1974): 16-19. Print.

Karlin, Athanasius "The Coming of the First Volga German Catholics to America." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (Winter 1978): 61-65. Print.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. Print.

Pleve, Igor. Beginning of the Emigration of the Volga Germans to America. Wolgadeutsche.net website, accessed March 4, 2019.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974. Print.

Smith, C. Henry. The Coming of the Russian Mennonites: An Episode in the Settling of the Last Frontier, 1874-1884. Berne, IN: Mennonite Book Concern, 1927. p. 125. Print.

Williams, Hattie Plum. The Czar's Germans: With Particular Reference to the Volga Germans. Ed. Emma S. Haynes, Phillip B. Legler, and Gerda Stroh. Walker. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1975. Print.

Hoelzer, John. "The Earliest Volga Germans in Sutton, Nebraska and Portion of Their History." Work Paper #16 of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (December 1974): 16-19. Print.

Karlin, Athanasius "The Coming of the First Volga German Catholics to America." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (Winter 1978): 61-65. Print.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. Print.

Pleve, Igor. Beginning of the Emigration of the Volga Germans to America. Wolgadeutsche.net website, accessed March 4, 2019.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974. Print.

Smith, C. Henry. The Coming of the Russian Mennonites: An Episode in the Settling of the Last Frontier, 1874-1884. Berne, IN: Mennonite Book Concern, 1927. p. 125. Print.

Williams, Hattie Plum. The Czar's Germans: With Particular Reference to the Volga Germans. Ed. Emma S. Haynes, Phillip B. Legler, and Gerda Stroh. Walker. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1975. Print.

Last updated December 7, 2023