Community > Education

Education

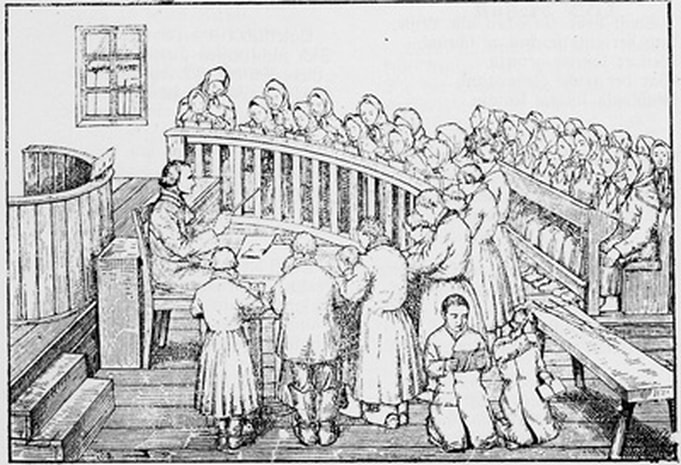

According to Volga German historian Igor Pleve, schools arose in the first year the colonists arrived on the Volga. In the first years of settlement, instruction of children from age 7 likely took place in private homes. By 1771, the colonists had constructed a wooden parochial school building, which also served as a prayer house. Soon afterward, a church was built. The school and church were established under the leadership of Pastor Johann Georg Herwig.

The church established the first school in Norka, which owned and operated it for the colonists' benefit. The church school made it compulsory to start classes at the age of seven, and students were permitted to leave at the age of fifteen. The schoolmaster worked under the supervision of the pastor of the church.

In the 1770s, a second school controlled by the Russian government was established under four conditions: 1) the community was to provide a piece of land for the school; 2) the community would construct the building; 3) the community would employ teachers and custodians; and, 4) the community would pay the teachers and provide living quarters for them. Although the school was funded exclusively by the residents of Norka, it remained under the control of the Inspector for Public Schools. Required subjects included the Law of God, reading and writing, the Russian language, and penmanship. Teachers were allowed to introduce supplemental courses.

The 1798 Census report for Norka made by the Russian Collegiate Assessor, Cavalier Sixtel, states that:

The church established the first school in Norka, which owned and operated it for the colonists' benefit. The church school made it compulsory to start classes at the age of seven, and students were permitted to leave at the age of fifteen. The schoolmaster worked under the supervision of the pastor of the church.

In the 1770s, a second school controlled by the Russian government was established under four conditions: 1) the community was to provide a piece of land for the school; 2) the community would construct the building; 3) the community would employ teachers and custodians; and, 4) the community would pay the teachers and provide living quarters for them. Although the school was funded exclusively by the residents of Norka, it remained under the control of the Inspector for Public Schools. Required subjects included the Law of God, reading and writing, the Russian language, and penmanship. Teachers were allowed to introduce supplemental courses.

The 1798 Census report for Norka made by the Russian Collegiate Assessor, Cavalier Sixtel, states that:

They have here their own pastor and parish church. Small children are taught reading, writing, and religion by a schoolmaster in a specially constructed school building.

Until 1861, the colonists had to provide the resources for their education system. A new Russian school was established in 1868 next to the church.

In 1890, a law was passed that required compulsory Russian language classes. From then on, the Mitteldorf school had two German and two Russian teachers.

By 1894, there were three schools in Norka: the parochial school, the government-supervised school, and a private cooperative school.

A. N. Minkh, in his description of Norka in 1898, also states that there were three schools in the colony. The schools were named for their location in the colony's upper, middle, and lower parts. As a result, the names given were the Oberdorf Schule, Mitteldorf Schule, and Unterdorf Schule.

In 1906, pastor and church leader Johannes Erbes reported that of the 13,336 residents living in Norka, 1,075 children between the ages of 7 and 15 were required to attend the government school. This school had three classrooms. He also noted that in contrast to other German colonies, attendance in Norka schools was nearly 100 percent. That same year, the church school enrolled 443 boys and 482 girls. Seven parochial school teachers taught in one large classroom.

During the Soviet era, all three established schools were closed and reconstituted as two elementary schools and one middle school. All of the schools and teachers were under government control.

Berta Schreiber (born in November 1914), a former Norka teacher, recalls five village schools. Berta's mother told her that the fifth school, known as the Klunden Schule, was privately operated by the Klund family.

In 1890, a law was passed that required compulsory Russian language classes. From then on, the Mitteldorf school had two German and two Russian teachers.

By 1894, there were three schools in Norka: the parochial school, the government-supervised school, and a private cooperative school.

A. N. Minkh, in his description of Norka in 1898, also states that there were three schools in the colony. The schools were named for their location in the colony's upper, middle, and lower parts. As a result, the names given were the Oberdorf Schule, Mitteldorf Schule, and Unterdorf Schule.

In 1906, pastor and church leader Johannes Erbes reported that of the 13,336 residents living in Norka, 1,075 children between the ages of 7 and 15 were required to attend the government school. This school had three classrooms. He also noted that in contrast to other German colonies, attendance in Norka schools was nearly 100 percent. That same year, the church school enrolled 443 boys and 482 girls. Seven parochial school teachers taught in one large classroom.

During the Soviet era, all three established schools were closed and reconstituted as two elementary schools and one middle school. All of the schools and teachers were under government control.

Berta Schreiber (born in November 1914), a former Norka teacher, recalls five village schools. Berta's mother told her that the fifth school, known as the Klunden Schule, was privately operated by the Klund family.

Norka native Conrad Brill recalls:

Two of the older Norka schools were replaced with new ones in about 1915. One in Oberdorf, and one in Unterdorf. The new and larger Russian school had been built next to the church in 1905 when we were ordered to learn the Russian language along with the German we had been wholly learning previously. The old Unterdorf school in my school days had been known as the Kaiser school. It was because it was located next to the property of a family named Kaiser. Old timers who came to America still referred to it as the Kaiser school.

In 1909 I had to go to Russian school in the Mitteldorf. Although our German folk had been in Russia for over a hundred years, we didn't fraternize with the Russians, dealing with them only in business matters... When I went to the Russian school in Mitteldorf, my teacher’s name was Hill. He was referred to as "Gigl Schnitter" (probably Gickel Schnitter or chicken catcher). I attended for about a year, then just stayed home and helped do the farming and hauling merchandise to help support the family... Some of our prosperous folk sent their sons to boarding school in Saratov, where they got a good education plus a chance to learn the Russian language. They, of course, landed the better jobs, both in civilian life and in the military services. Most of us farm lads were content to get through school as quickly as possible.

The Schulmeister (schoolmaster or principal) was regarded as a person of great importance in the colony because of his position and the fact that he acted as the assistant pastor. Religion and education were closely interrelated in the classroom because the primary textbooks were the Biblische Geschichte (Bible Stories), the Catechism, the Bible, and the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga Song Book).

Ludwig Battin, a Catholic teacher who migrated from Paris, France, was among the first settlers in Norka in 1767. Due to his Catholic beliefs, he was not allowed to teach the Reformed and Lutheran children. The first Schulmeister in Norka was Peter Pauly (Pauli). Schulmeister-Küster Johannes Kaiser (Abt. 1770-1836) served until 1814. From 1814 to 1815, Johannes Romeis served as Schulmeister. Johann Heinrich Schnell (1794-1855) served as a schoolmaster in Norka, Stephan, Köhler, and Neu-Norka colonies from about 1820 to his death in Neu-Norka in 1855. From 1870 to 1890, Johannes Rudolph served as Schulmeister at the Unterdorf school. Carl Leonhardt served from 1902 to 1919 and was replaced by Alexander Leonhardt, who quit in 1929.

The Schulmeister sometimes replaced the pastor in leading the ordinary worship service, and, in some cases, he performed at funerals and baptisms when the pastor was unavailable. The Schulmeister also assisted the pastor in the visitation of the sick, along with one or two church elders. The Schulmeister wore a jacket with long tails, a formality to be worn in the church. The Schulmeister sometimes wore a small cross-stitch tie, symbolizing the Protestant reformers Luther and Zwingli.

Ludwig Battin, a Catholic teacher who migrated from Paris, France, was among the first settlers in Norka in 1767. Due to his Catholic beliefs, he was not allowed to teach the Reformed and Lutheran children. The first Schulmeister in Norka was Peter Pauly (Pauli). Schulmeister-Küster Johannes Kaiser (Abt. 1770-1836) served until 1814. From 1814 to 1815, Johannes Romeis served as Schulmeister. Johann Heinrich Schnell (1794-1855) served as a schoolmaster in Norka, Stephan, Köhler, and Neu-Norka colonies from about 1820 to his death in Neu-Norka in 1855. From 1870 to 1890, Johannes Rudolph served as Schulmeister at the Unterdorf school. Carl Leonhardt served from 1902 to 1919 and was replaced by Alexander Leonhardt, who quit in 1929.

The Schulmeister sometimes replaced the pastor in leading the ordinary worship service, and, in some cases, he performed at funerals and baptisms when the pastor was unavailable. The Schulmeister also assisted the pastor in the visitation of the sick, along with one or two church elders. The Schulmeister wore a jacket with long tails, a formality to be worn in the church. The Schulmeister sometimes wore a small cross-stitch tie, symbolizing the Protestant reformers Luther and Zwingli.

The Schulmeister was also responsible for the teachers who served at the village schools. According to Emma Schwabenland Haynes, it was customary to choose teachers whose chief qualification consisted of a willingness to serve for a small amount of money. In some cases, the school teachers had difficulty reading and writing, and as they usually had hundreds of children under their care, it is easy to assume that they could not teach them a great deal. Many of the pastors tried to pass laws to improve their parish's educational conditions, but as a whole, school rooms remained crowded.

An excerpt from the Autobiography of Jacob Miller, written in 1936, provides further insights on the subject of education:

An excerpt from the Autobiography of Jacob Miller, written in 1936, provides further insights on the subject of education:

"I, Jacob Miller, as the second to the oldest son of my parents, Johannes Peter and Elisabeth Miller, was born on the 2nd day of July, 1871, in the colony of Norka, Saratov, Russia, a colony of about 11,000 people at that time.

My father was a well-to-do farmer and was able to give his children an education. There were three large school houses in this colony in which was taught mostly religion and reading, writing and arithmetic.

The teachers were all German teachers. Only about 75 children, all boys, had a separate schoolroom and were taught history and geography, in the Russian language, and grammar in both German and Russian. I and my four brothers were privileged to attend this school. The rest of the children did not know anything about the outside world, only what someone had told them.

There were no newspapers of any kind, except the pastor of the church, which was a Reformed church, got a few copies of a church paper from Germany.

I was confirmed at the age of 14, and at that time my father had leased a farm away from the colony. In connection with the farm was a small water power flour mill which only ground about 75 bushels of grain in 24 hours. Besides this we kept cattle and sheep, and hogs. Since the land was very productive we were doing very well.

When I was 16 years of age I was permitted to go to high school in a neighboring colony, Grimm (Lesnoi Karamysch). I soon got to the last class, and on my father's uncle's advice I had to quit without finishing high school. But my youngest brother, Peter, was privileged to go through the university."

James Long writes that in the late 1800s, clerical authority in the colonies had begun to diminish. This coincided with a rising secular elite who received their education at the central schools in Lesnoi Karamysh (Grimm) and Katharinenstadt (now Marx), established in the 1830s. Long states that these two schools produced almost all teachers, village clerks, and colony leaders throughout the Volga German settlement area.

Advanced educational opportunities at the technical and vocational school in the city of Engels were afforded to some of the youth.

Advanced educational opportunities at the technical and vocational school in the city of Engels were afforded to some of the youth.

George Philip Lehl, born in Norka in 1900, recalls that people would compress the manure cleaned from their barns into blocks, which dried in the sun. This material was known as Mistholz (manure wood). The blocks helped pay for their children's education as each family contributed 75 blocks to heat the school during cold weather.

The education system continued to improve under the Soviet regime, and by the 1930s, it was common to have professional teachers in the schools. By the mid-1930s, government-controlled schools had entirely replaced the church school system.

The Soviet education system was short-lived, as the deportation in 1941 ended any type of formal learning for most of the Volga Germans for many years to come.

Sources

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 46-47. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan. 1798 Census of the German Colonies along the Volga: Economy, Population, and Agriculture. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1999. Print.

Miller, Jacob. Autobiography of Jacob Miller, 1936.

Molsberger, Tobias. Das Schulsystem Der Wolgadeutschen Zwischen 1767 Und 1917. Norderstedt, Germany: Grin Verlag, 2014. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. 219-42. Print.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown. 6-7.

Schnell, Ruth Ann. Provided Information about Johann Heinrich Schnell.

"You know, Garbagemen are the cleanest people." The Builder [Coos Bay, Oregon], circa 1976.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 46-47. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan. 1798 Census of the German Colonies along the Volga: Economy, Population, and Agriculture. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1999. Print.

Miller, Jacob. Autobiography of Jacob Miller, 1936.

Molsberger, Tobias. Das Schulsystem Der Wolgadeutschen Zwischen 1767 Und 1917. Norderstedt, Germany: Grin Verlag, 2014. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. 219-42. Print.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown. 6-7.

Schnell, Ruth Ann. Provided Information about Johann Heinrich Schnell.

"You know, Garbagemen are the cleanest people." The Builder [Coos Bay, Oregon], circa 1976.

Last updated February 3, 2024