Interview with Berta Schreiber

Berta Schreiber was born in Norka on November 2, 1914, the daughter of Wilhelm Conrad Schreiber (born 1872) and Catharina Margaretha Hohnstein (born 1878).

Berta grew up in Norka and lived there until the deportation of all ethnic Germans in 1941. Berta was forced to work in the Trudarmee (labor army) in Siberia. She later immigrated to Germany, where she lived the last years of her life.

Berta Schreiber died March 29, 2003 in Köln, Germany.

Berta grew up in Norka and lived there until the deportation of all ethnic Germans in 1941. Berta was forced to work in the Trudarmee (labor army) in Siberia. She later immigrated to Germany, where she lived the last years of her life.

Berta Schreiber died March 29, 2003 in Köln, Germany.

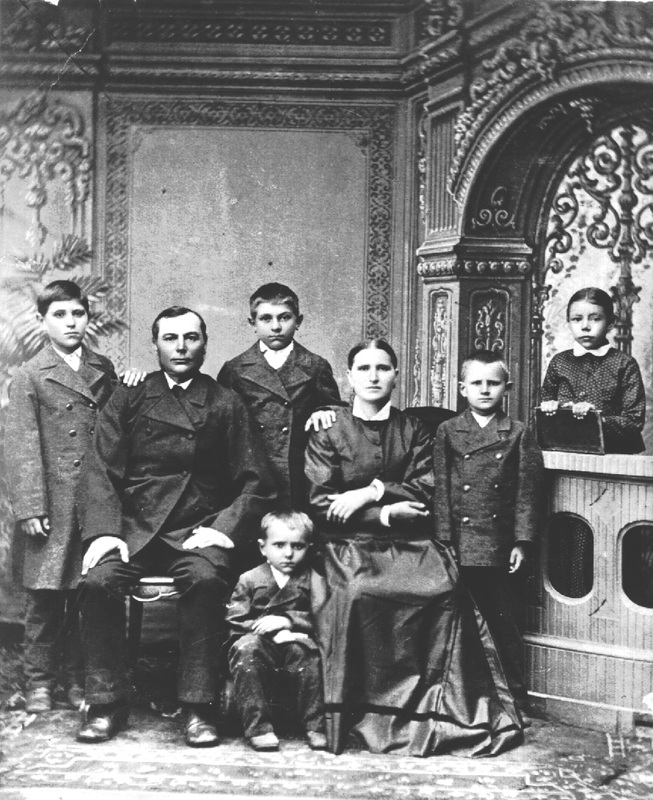

Family of Wilhelm Conrad Schreiber. Wilhelm is seated with arms crossed. At left in the photo is his daughter Olga, seated on the right is his son Vladimir, further right stands Alexander, near to Alexander is daughter, Berta Schreiber, further right is Wilhelm's wife, Ekaterina, holding Johann Schreiber. At the extreme right is Friedrich. Daughter Maria (married name of Weber) sits in the foreground. The youngest son Vasily is not shown in the photograph. Wilhelm died in 1921 at the age of 49 years. He was an avid hunter and caught a severe cold while hunting and died. Photograph courtesy of Elvira Schreiber.

English Translation of the interview with Berta Schreiber.

I – Interviewer (Mrs. Wolf)

B – Berta Schreiber

I: What is your name?

B: My name is Berta Schreiber.

I: When and where were you born?

B: I was born on the 2nd of November 1914 in the village Norka, in Russia. But I did not always live there. My parents moved after my birth to the village of Oktarskoe, near Saratov. My father has founded his own business there. We had a little butcher shop. Then we have lived in a village named Kochetovka. This village was located near the Volga River as well. After a time my parents moved back to Norka. My father worked in a shop as a salesman. Then came the Revolution. My father died in 1921 of pneumonia. We were 8 children - 5 boys and 3 girls. So, I grew up in Norka and went to school there. In the year 1928, began the Gulag. In this year a 7-year school was begun. I finished this school - all 7 classes. After the school I moved to the city of Engels. Engels was the capital of the Volga German Republic at that time. I started my education in a cooperative technical college, in 1st course, bookkeeper department. In 1933, I started my training and in 1937 I finished it with the profession of bookkeeper. Then I had to work in a Russian canton, named Krasny Kut. I have made a long one-year internship there. After that I wanted to go back to my family in Norka, but there was no position available as bookkeeper. Then they made a suggestion for me to teach in the school, in which I have learned myself. I said, I have no training as a teacher, but if I can do it, I will do it. Then I get the instruction to teach there.

I: Which subjects did you teach?

B: I have taught all subjects from the 1st till 4th class. It was a primary school. I have worked 3 years there, then came the year 1941 and we all had to go away.

I: You said, that you were one of 8 children. What are the names of your other brothers and sisters?

B: Well, the oldest sister was Olga (Olinde), the 2nd – Maria. The oldest married a Schleuning (Schleining). The people always called him Reicher Schleuning (part of the "rich" Schleuning family).

I: Was he rich?

B: Yes, they were the richest family in the village. After the Gulag they were deported to the Soviet Republic of Komi. In 1941 they were sent to a work camp (Trudarmee) in Chelyabinsk, Russia. Her husband died there in 1941. (Note: Per Lydia Hammerschmidt he died in April 1943)

Maria married as well, to Johannes Weber. He was a bookkeeper in the kolkhoz (collective). In 1941, Johannes Weber was arrested. He died in captivity.

In 1943 I came in the Trudarmee in Nizhniy Tagil. There I have worked in an armaments factory, a tank factory. In 1943 I came there, and in 1948 I was released. Then I came to my new home in Zavyalovskiy rayon, Altai region in West Siberia. I could not work as teacher there, so I became a bookkeeper. My brother was a bookkeeper as well. The other brothers… well, one died in the Trudarmee, the other, Alexander, came back; Waldemar came back too. Johannes was in the war in captivity, 10 years long. He died after two years, I think. So we all were scattered.

I: What are the names of your parents?

B: My father is Wilhelm Schreiber. My mother is Katharina Schreiber, née Hohnstein.

I: Can you remember your grandparents?

B: I can't say something exactly about my grandparents. My grandfather was Conrad. That’s him (Berta is looking at the photo below), 2nd from left to right. This is my grandmother Christina, née Sinner (2nd from right to left). This is the brother of my father Lorenz (1st from left to right) and he died in America. The 1st from right is Alexander and this is Johannes (In the lower row). In the middle (standing) is my father Wilhelm. He had also other sisters but they are not shown on this photo (note: the photo Berta was holding did not include the girl shown on the right). These were Natalia, Amelia and Katja. Katja has married a Russian. They are also immigrated to America, but they came back to Russia after a time. All of these, other than my father, have immigrated to America.

I – Interviewer (Mrs. Wolf)

B – Berta Schreiber

I: What is your name?

B: My name is Berta Schreiber.

I: When and where were you born?

B: I was born on the 2nd of November 1914 in the village Norka, in Russia. But I did not always live there. My parents moved after my birth to the village of Oktarskoe, near Saratov. My father has founded his own business there. We had a little butcher shop. Then we have lived in a village named Kochetovka. This village was located near the Volga River as well. After a time my parents moved back to Norka. My father worked in a shop as a salesman. Then came the Revolution. My father died in 1921 of pneumonia. We were 8 children - 5 boys and 3 girls. So, I grew up in Norka and went to school there. In the year 1928, began the Gulag. In this year a 7-year school was begun. I finished this school - all 7 classes. After the school I moved to the city of Engels. Engels was the capital of the Volga German Republic at that time. I started my education in a cooperative technical college, in 1st course, bookkeeper department. In 1933, I started my training and in 1937 I finished it with the profession of bookkeeper. Then I had to work in a Russian canton, named Krasny Kut. I have made a long one-year internship there. After that I wanted to go back to my family in Norka, but there was no position available as bookkeeper. Then they made a suggestion for me to teach in the school, in which I have learned myself. I said, I have no training as a teacher, but if I can do it, I will do it. Then I get the instruction to teach there.

I: Which subjects did you teach?

B: I have taught all subjects from the 1st till 4th class. It was a primary school. I have worked 3 years there, then came the year 1941 and we all had to go away.

I: You said, that you were one of 8 children. What are the names of your other brothers and sisters?

B: Well, the oldest sister was Olga (Olinde), the 2nd – Maria. The oldest married a Schleuning (Schleining). The people always called him Reicher Schleuning (part of the "rich" Schleuning family).

I: Was he rich?

B: Yes, they were the richest family in the village. After the Gulag they were deported to the Soviet Republic of Komi. In 1941 they were sent to a work camp (Trudarmee) in Chelyabinsk, Russia. Her husband died there in 1941. (Note: Per Lydia Hammerschmidt he died in April 1943)

Maria married as well, to Johannes Weber. He was a bookkeeper in the kolkhoz (collective). In 1941, Johannes Weber was arrested. He died in captivity.

In 1943 I came in the Trudarmee in Nizhniy Tagil. There I have worked in an armaments factory, a tank factory. In 1943 I came there, and in 1948 I was released. Then I came to my new home in Zavyalovskiy rayon, Altai region in West Siberia. I could not work as teacher there, so I became a bookkeeper. My brother was a bookkeeper as well. The other brothers… well, one died in the Trudarmee, the other, Alexander, came back; Waldemar came back too. Johannes was in the war in captivity, 10 years long. He died after two years, I think. So we all were scattered.

I: What are the names of your parents?

B: My father is Wilhelm Schreiber. My mother is Katharina Schreiber, née Hohnstein.

I: Can you remember your grandparents?

B: I can't say something exactly about my grandparents. My grandfather was Conrad. That’s him (Berta is looking at the photo below), 2nd from left to right. This is my grandmother Christina, née Sinner (2nd from right to left). This is the brother of my father Lorenz (1st from left to right) and he died in America. The 1st from right is Alexander and this is Johannes (In the lower row). In the middle (standing) is my father Wilhelm. He had also other sisters but they are not shown on this photo (note: the photo Berta was holding did not include the girl shown on the right). These were Natalia, Amelia and Katja. Katja has married a Russian. They are also immigrated to America, but they came back to Russia after a time. All of these, other than my father, have immigrated to America.

I: Have you had connections together?

B: We had connections to a sister of my father. These are the other 3 sisters of my father. (Photo 2.) From right to left are: Katja, Emilia, Natalia. This is Natalia as well. (Photo 3.) And this is the father of Kathleen Svoboda, Johannes. This is Tatiana (also Lydia) the daughter of…. (Photo 5.) This is Christina, the mother of my father. This photo was taken already in America. (Photo 6.)

I: Where did you live in Norka? It was a big village, wasn't it?

B: At first we lived in a rented house. Later, we bought our own house. It was in the 1st row.

I: The streets had no names, right? There were only 1st, 2nd, 3rd row, and so on.

B: Yes, that’s right. Later the streets were called with names, but I don't know these now. I can remember yet, that the 7th row was the last, so we had altogether 7 streets.

I: And how long were the streets approximately?

B: I don't know exactly, I think 1.5 kilometers long.

I: Who were your neighbors?

B: The neighbours were Vogler (Fegler) and Becker.

I: Which families from Norka can you remember yet?

B: There were: Vogler, Schreiber, Becker, Häuser, Krieger, Bauer, Helzer, Schlitt, Schmidt, Schnell, Weber. Then there were Traudt yet. Reich was also a family there.

I: Which businesses were there, in Norka?

B: At first there was a Sarpinka mill – a weaving mill. They manufactured cotton cloth there. In the room, where the women worked, stood a Webstuhl (weaving chair) The machine was considerably wide and long, and then you sat behind it and pulled it back and forth. Then they dyed the cotton with colors.

I: What else was there yet?

B: Well, what else was there yet? There was cooperative – Selpo. The people called it Dorf Konsum Verein (village cooperative association). At that time there were already kolkhoz's under the communist government. There was also a mill. There was a hospital in the village as well.

I: Which shops and stores were there?

B: There was one from Spady; there was also one named Silpsi. There was a joiner’s workshop.

I: Were the all stores private?

B: No, no. Everything was owned by the government. There was a private mill owned by the Spady family, but it was destroyed with the times. The mill was built with bricks, and the people built chimneys with these bricks after the mill was destroyed.

I: How many schools were there, in Norka? Were there two schools or only one big school?

B: No, No. There were five schools! This school, you showed me, where is it? Here. I can’t remember this school. But there were five schools, in Norka, exactly. These were schools for the primary classes, for the middle classes and for the higher classes.

I: My mother has told me, that there was also a private school.

B: Yes, yes. It was a school named the “Klunden – Schule”. That’s right. The school was from the Klund family.

I: There was also a big church….

B: Yes, exactly! A big church! As the Gulag has begun and the communists came, they took the cross down and they used the church as storage space for grain. The winter church (school house), which was built with timber, was made into a culture club.

I: Were you there when they took the cross down and closed the church?

B: No, I wasn’t. I have heard it, but I haven’t seen it.

I: Miss Schreiber, which subjects did you like as a pupil? And which subjects did you like teach and which not?

B: Well, why not? They gave me a general education. These were German language, geography, Russian language, biology and etcetera. These subjects were in the primary school. I did like my work and I did like to learn.

Furthermore, I worked as secretary in the school. I have yet made the training in the bookkeeping and for that reason as well they gave me this job. I was a member in the grade conference and I have discussed together with the director and the teachers about the grades and general assessments of pupils. Then I had to write a report and send it to our district center.

I: Did you have a nickname?

B: Nickname? No, I had nothing like this! No.

I: Which German customs and feasts do remember and have experienced in Norka?

B: Yes, the feasts and holidays like Christmas, Easter, and Feast of the Ascension, and then of course the Soviet holidays.

I: Miss Schreiber, can you remember your grandparents?

B: No, I can no longer. I cannot remember them any longer. They did not live in Norka. My mother sometimes told me about them, but can I can no longer remember. I would have so many questions for my mother, but there is nobody alive who can give me the answers. And the young generations, the young people, they are not interested in this.

I: How was life in general for your family in Norka?

B: Well, we were not farmers, my oldest brother was bookkeeper, the 2nd brother was a bookkeeper as well, the 3rd brother was the director of the mill, the 4th brother was a manager in a library, then he came in the army, in the war he was in captivity.

I: How old were you when you were deported?

B: I was 26 years old at the time.

I: Was your life very changed through that? Did you experience severe hunger?

B: No, no. We haven't hungered. We haven't hungered in the Trudarmee; I can't confirm it, but some people had a very terrible famine, some people even died of hunger. Certainly, as we came there, the people said, that a big number of people died of hunger, approximately 30,000, but I don’t know if it is right or false.

As we came in the Trudarmee, we at first had to build the “Trans Siberian”, it was in Slavgorod, from over there we came then to Nizhniy Tagil. We came to work at an armaments factory, where we produced the tanks. We were most only young people there, 18, 19, 20, 23 years old. We had to sign a document that we would not write in our letters to our families what type of work we did. We have got 1 kg bread and good food from America. The food was only for those who worked in this factory. Then we worked in a harmful mine where there were dangerous gases and dust. Many people were already dead.

I: My father was also worked at this mine. He died when he was 40.

B: Yes, yes! I can remember him.

Well, we came there and were allocated to different mines. The factory was underground. They asked us for our education. They gave me a job in the office of the factory, as I had the bookkeeper profession. But then came a Jew and she also had to work in the mine like all the other people (note: presumably she took Berta's job). In this way I worked with the shovel until the end in 1946. After that they wanted to send us in a gold mine. They assembled us, mostly the young people, but the director of the factory did not to give us up. We were 3 days under convoy until the director came from Moscow with a document, which forbade us from going to the gold mine. After that I worked in a kolkhoz until September 1948. We earned well. After that we could decide if we want to stay there or to go home. I decided to go back to my family.

– END –

B: We had connections to a sister of my father. These are the other 3 sisters of my father. (Photo 2.) From right to left are: Katja, Emilia, Natalia. This is Natalia as well. (Photo 3.) And this is the father of Kathleen Svoboda, Johannes. This is Tatiana (also Lydia) the daughter of…. (Photo 5.) This is Christina, the mother of my father. This photo was taken already in America. (Photo 6.)

I: Where did you live in Norka? It was a big village, wasn't it?

B: At first we lived in a rented house. Later, we bought our own house. It was in the 1st row.

I: The streets had no names, right? There were only 1st, 2nd, 3rd row, and so on.

B: Yes, that’s right. Later the streets were called with names, but I don't know these now. I can remember yet, that the 7th row was the last, so we had altogether 7 streets.

I: And how long were the streets approximately?

B: I don't know exactly, I think 1.5 kilometers long.

I: Who were your neighbors?

B: The neighbours were Vogler (Fegler) and Becker.

I: Which families from Norka can you remember yet?

B: There were: Vogler, Schreiber, Becker, Häuser, Krieger, Bauer, Helzer, Schlitt, Schmidt, Schnell, Weber. Then there were Traudt yet. Reich was also a family there.

I: Which businesses were there, in Norka?

B: At first there was a Sarpinka mill – a weaving mill. They manufactured cotton cloth there. In the room, where the women worked, stood a Webstuhl (weaving chair) The machine was considerably wide and long, and then you sat behind it and pulled it back and forth. Then they dyed the cotton with colors.

I: What else was there yet?

B: Well, what else was there yet? There was cooperative – Selpo. The people called it Dorf Konsum Verein (village cooperative association). At that time there were already kolkhoz's under the communist government. There was also a mill. There was a hospital in the village as well.

I: Which shops and stores were there?

B: There was one from Spady; there was also one named Silpsi. There was a joiner’s workshop.

I: Were the all stores private?

B: No, no. Everything was owned by the government. There was a private mill owned by the Spady family, but it was destroyed with the times. The mill was built with bricks, and the people built chimneys with these bricks after the mill was destroyed.

I: How many schools were there, in Norka? Were there two schools or only one big school?

B: No, No. There were five schools! This school, you showed me, where is it? Here. I can’t remember this school. But there were five schools, in Norka, exactly. These were schools for the primary classes, for the middle classes and for the higher classes.

I: My mother has told me, that there was also a private school.

B: Yes, yes. It was a school named the “Klunden – Schule”. That’s right. The school was from the Klund family.

I: There was also a big church….

B: Yes, exactly! A big church! As the Gulag has begun and the communists came, they took the cross down and they used the church as storage space for grain. The winter church (school house), which was built with timber, was made into a culture club.

I: Were you there when they took the cross down and closed the church?

B: No, I wasn’t. I have heard it, but I haven’t seen it.

I: Miss Schreiber, which subjects did you like as a pupil? And which subjects did you like teach and which not?

B: Well, why not? They gave me a general education. These were German language, geography, Russian language, biology and etcetera. These subjects were in the primary school. I did like my work and I did like to learn.

Furthermore, I worked as secretary in the school. I have yet made the training in the bookkeeping and for that reason as well they gave me this job. I was a member in the grade conference and I have discussed together with the director and the teachers about the grades and general assessments of pupils. Then I had to write a report and send it to our district center.

I: Did you have a nickname?

B: Nickname? No, I had nothing like this! No.

I: Which German customs and feasts do remember and have experienced in Norka?

B: Yes, the feasts and holidays like Christmas, Easter, and Feast of the Ascension, and then of course the Soviet holidays.

I: Miss Schreiber, can you remember your grandparents?

B: No, I can no longer. I cannot remember them any longer. They did not live in Norka. My mother sometimes told me about them, but can I can no longer remember. I would have so many questions for my mother, but there is nobody alive who can give me the answers. And the young generations, the young people, they are not interested in this.

I: How was life in general for your family in Norka?

B: Well, we were not farmers, my oldest brother was bookkeeper, the 2nd brother was a bookkeeper as well, the 3rd brother was the director of the mill, the 4th brother was a manager in a library, then he came in the army, in the war he was in captivity.

I: How old were you when you were deported?

B: I was 26 years old at the time.

I: Was your life very changed through that? Did you experience severe hunger?

B: No, no. We haven't hungered. We haven't hungered in the Trudarmee; I can't confirm it, but some people had a very terrible famine, some people even died of hunger. Certainly, as we came there, the people said, that a big number of people died of hunger, approximately 30,000, but I don’t know if it is right or false.

As we came in the Trudarmee, we at first had to build the “Trans Siberian”, it was in Slavgorod, from over there we came then to Nizhniy Tagil. We came to work at an armaments factory, where we produced the tanks. We were most only young people there, 18, 19, 20, 23 years old. We had to sign a document that we would not write in our letters to our families what type of work we did. We have got 1 kg bread and good food from America. The food was only for those who worked in this factory. Then we worked in a harmful mine where there were dangerous gases and dust. Many people were already dead.

I: My father was also worked at this mine. He died when he was 40.

B: Yes, yes! I can remember him.

Well, we came there and were allocated to different mines. The factory was underground. They asked us for our education. They gave me a job in the office of the factory, as I had the bookkeeper profession. But then came a Jew and she also had to work in the mine like all the other people (note: presumably she took Berta's job). In this way I worked with the shovel until the end in 1946. After that they wanted to send us in a gold mine. They assembled us, mostly the young people, but the director of the factory did not to give us up. We were 3 days under convoy until the director came from Moscow with a document, which forbade us from going to the gold mine. After that I worked in a kolkhoz until September 1948. We earned well. After that we could decide if we want to stay there or to go home. I decided to go back to my family.

– END –

Source

Interview and transcript used with the permission of Alex Wolf and Berta Schreiber, Köln, Germany, October 2002.

Last updated January 4, 2023.