Traditions > Folk Music

Folk Music

The original colonists brought with them the traditional folk music of their homelands. There were no songbooks with notes in the Volga colonies, but they lived on in the memories of older people and were renewed through the singing of young single men.

We sang the song in friendship,

and who composed the tune?

All we Germans did it,

packed up from Germany.

-- Georg Schünemann

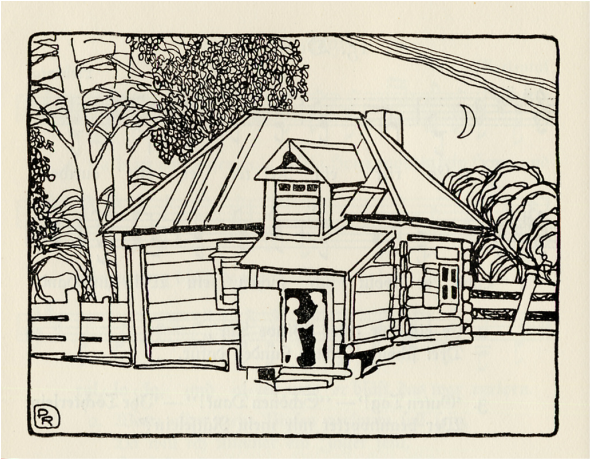

For young people, singing Gasse Lieder (street songs) was a primary form of recreation and amusement. The Gasse Lieder could often be playful and sometimes bawdy. Young men would gather at a street corner and take up a song and then proceed to a girl's house, where they would sing the most beautiful songs they knew, including love songs and ballads. Then, they would meet their girlfriends and continue singing with continuous variations and embellishments. Some played the harmonica, and they often danced with the girls until it was time to take them home. The songs didn't end until the early morning on warm summer nights.

Homeland songs, maternal tones,

folksongs dear and trusted,

whether spun in distant land,

or in native homeland,

move so gently through your soul,

leave behind there deepest tracks.

-- Peter Sinner

Songs were exchanged when farmers from different colonies met for a rest in the fields or on the roads between villages. This practice made the number of songs and variations almost inexhaustible.

Two of the favorite songs were In einem kühlen Grunde da geht ein Mühlenrad (Down in the Cool Meadows, a Mill Wheel Turns) and O Straßburg, O Straßburg, du wunderschöne Stadt (O Strassburg, O Strassburg, You Beautiful City) which were reminders of their ancestral homes.

Many religious holidays incorporated folk singing, dancing, and religious music. Young people and the older generations would dance fast polkas and the "skipping" waltz (known in North American settlements as the Dutch Hop).

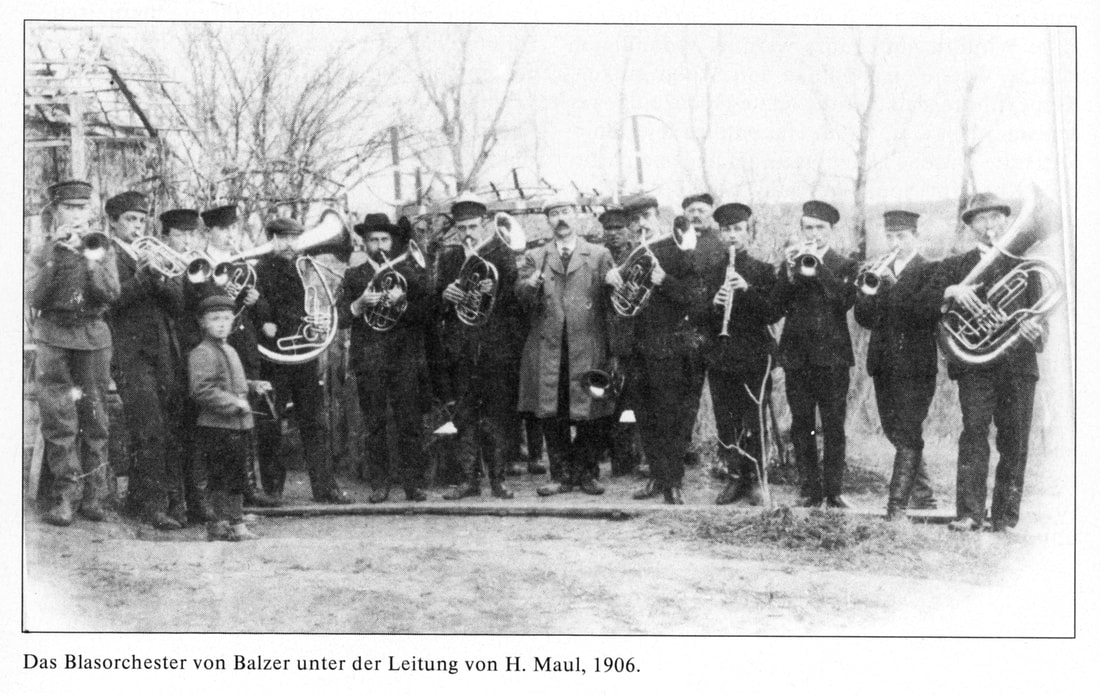

Bands would play on festive occasions such as holidays and weddings. The Hackbrett (hammered dulcimer), Zieharmonika (accordion), violin, and brass instruments were commonly used. The accordion was invented about 1845 in Vienna, Austria, and it would have taken some time to find its way to the lower Volga region. Before that time, the violin provided the primary structure to the music.

Two of the favorite songs were In einem kühlen Grunde da geht ein Mühlenrad (Down in the Cool Meadows, a Mill Wheel Turns) and O Straßburg, O Straßburg, du wunderschöne Stadt (O Strassburg, O Strassburg, You Beautiful City) which were reminders of their ancestral homes.

Many religious holidays incorporated folk singing, dancing, and religious music. Young people and the older generations would dance fast polkas and the "skipping" waltz (known in North American settlements as the Dutch Hop).

Bands would play on festive occasions such as holidays and weddings. The Hackbrett (hammered dulcimer), Zieharmonika (accordion), violin, and brass instruments were commonly used. The accordion was invented about 1845 in Vienna, Austria, and it would have taken some time to find its way to the lower Volga region. Before that time, the violin provided the primary structure to the music.

George Dinges recorded the music and lyrics of many Volga German folksongs in Wolgadeutsche Lieder (Volga German Songs). Georg Schünemann also published many folk songs in his book Das Lied der deutschen Kolonisten in Russland (The Song of the German Colonists in Russia).

Traditional Volga German polka music and dance became known as Dutch Hop in the United States and Canada. The word Dutch is a misnomer that most likely came from a misunderstanding of Deutsch (German). Many Volga Germans say their ancestors deliberately ignored the misunderstanding because of the widespread anti-German sentiments they encountered during World War I. So, the music remains Dutch Hop to this day.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources

Dinges, G. Wolgadeutsche Volkslieder Mit Bildern Und Weisen (Volga German Folk Songs with Images and Ways). Berlin: W. De Gruyter, 1932. Print.

Erina, E. M., and V. E. Salʹkova. Obychai Povolzhskikh Nemt︠s︡ev = Sitten Und Bräuche Der Wolgadeutschen. Moskva: Gotika, 2000. Print.

Olson, Marie Miller, and Anna Miller Reisbick. Norka, a German Village in Russia. Lincoln, Nebraska: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1986. 22. Print.

Schünemann, Georg. Das Lied Der Deutschen Kolonisten in Russland. München: Drei Masken Verlag, 1923. Print.

Sinner, Peter. Germans in the Land of the Volga. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1989. Print.

Walters, George J. Wir Wollen Deutsche Bleiben (We Want to Remain German): The Story of the Volga Germans. Kansas City, MO: Halcyon House, 1982. Pages 133-175. Print.

Erina, E. M., and V. E. Salʹkova. Obychai Povolzhskikh Nemt︠s︡ev = Sitten Und Bräuche Der Wolgadeutschen. Moskva: Gotika, 2000. Print.

Olson, Marie Miller, and Anna Miller Reisbick. Norka, a German Village in Russia. Lincoln, Nebraska: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1986. 22. Print.

Schünemann, Georg. Das Lied Der Deutschen Kolonisten in Russland. München: Drei Masken Verlag, 1923. Print.

Sinner, Peter. Germans in the Land of the Volga. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1989. Print.

Walters, George J. Wir Wollen Deutsche Bleiben (We Want to Remain German): The Story of the Volga Germans. Kansas City, MO: Halcyon House, 1982. Pages 133-175. Print.

Last updated November 28, 2023