History > Journey to the Volga

Journey to the Volga 1766 to 1767

After completing the sea journey and arrival processing in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov), the colonists were transported to nearby St. Petersburg. Once again, they were organized into transport groups of 600 to 1,000 colonists. The transport groups were led by Russian military officers who would escort them to the settlement sites on the lower Volga River near the frontier fortress town of Saratov. The transport groups were formed, considering family kinships, friendships, and religious faith. Lists of the colonists were made for each transport group and for those hospitalized along the way. Some of these lists have been preserved and translated.

Volga German historian Jakob Dietz describes three routes the colonists took to the Lower Volga settlement areas. The earliest route went largely overland and was deemed too difficult, time-consuming, and expensive. The second route was primarily on water and followed the Neva River through the Schlüsselburg Canal (now known as the Ladoga Canal), which avoided entering the storm-prone Lake Ladoga. The colonists then traveled down the Vohlkov River into Lake Ilmen. There was a portage to the headwaters of the Volga River near Tver and then a 1,100-mile voyage downriver to Saratov.

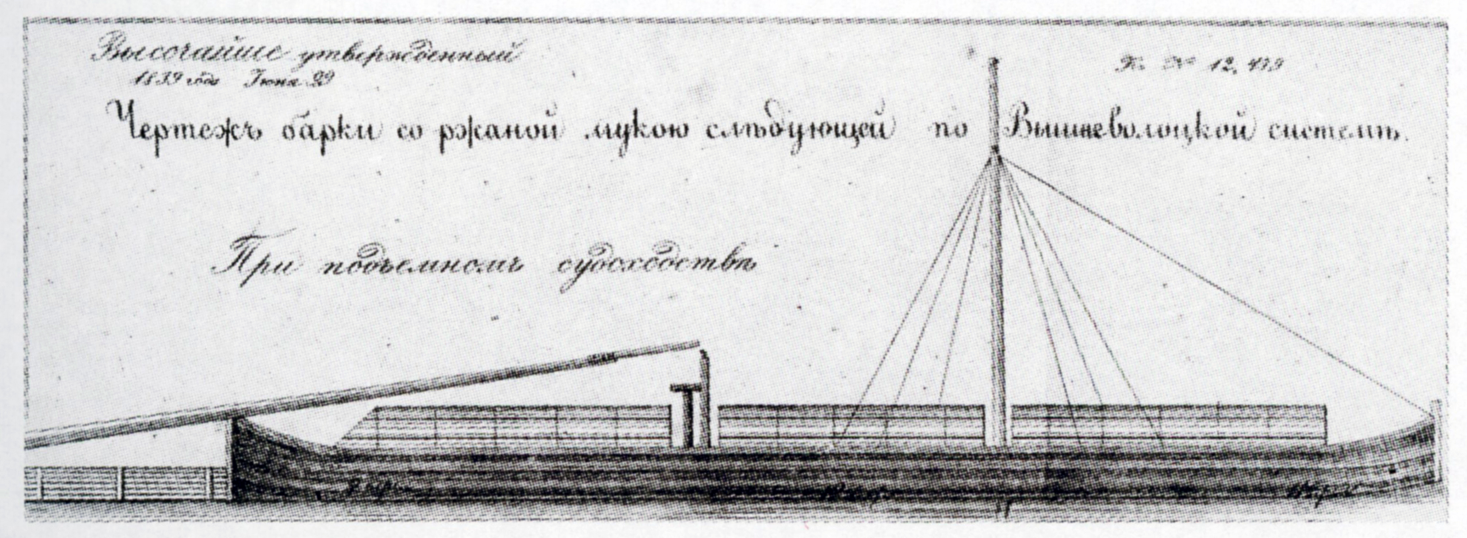

A third route was used in 1766 when those settling in Norka traveled to the lower Volga River area. The first part of the journey used the Mariinsky System, intended to connect St. Petersburg on the Baltic Sea with Rybinsk on the upper Volga River over time. Work on this waterway began in 1709 under Peter the Great, but the whole system was not complete in 1766.

A third route was used in 1766 when those settling in Norka traveled to the lower Volga River area. The first part of the journey used the Mariinsky System, intended to connect St. Petersburg on the Baltic Sea with Rybinsk on the upper Volga River over time. Work on this waterway began in 1709 under Peter the Great, but the whole system was not complete in 1766.

This route also followed the Neva River upstream into the Schlüsselberg Canal, which skirted the south shore of Lake Ladoga. From the canal, they continued into the mouth of the Sivr River and continued upstream to its headwaters at Lake Onega. The colonists sailed from Lake Onega into the Vytegra River and down the Kovzha River to Beloye (White) Lake.

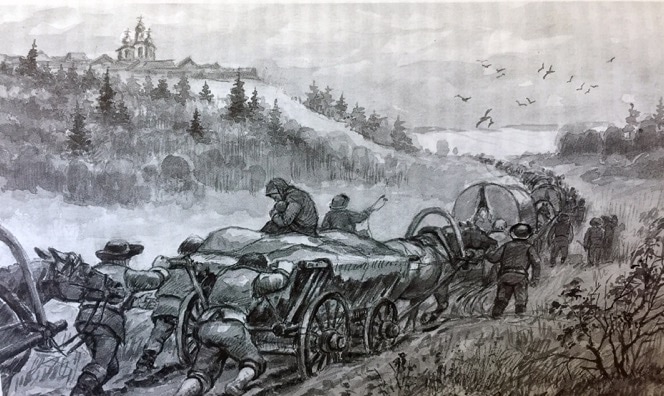

At the time, there was probably a short overland portage between the Vytegra River and the Kovzha River (the two rivers are now joined by a canal). The portage was accomplished by horse-drawn wagon. Women, children, and baggage were loaded aboard the wagons, and the able-bodied men walked.

At the southeast edge of White Lake, the colonists entered the Sheksna River, which flows into the Volga River at Rybinsk.

Given that the Volga River freezes for most of its length for three months each year, the colonists likely spent their first winter and Christmas with Russian peasant families somewhere along the Sheksna River.

The Russian government planned for winter quartering and paid local peasant families to shelter the colonists. The colonists used their travel allowance to buy food and supplies. This practice ensured a measure of hospitality for the colonists and an environment where they could learn more about Russian customs, foods, and the language during their stay.

In the spring, when the river was again navigable, the transport groups continued approximately 1,000 miles down the meandering Volga to the frontier town of Saratov, passing through the old Russian heartland cities of Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, Ulyanovsk, and Samara.

It is interesting to note that this route from the Gulf of Finland to the lower Volga was established by Viking traders over 1,000 years earlier. The Vikings traveled regularly between Scandinavia and the Caspian Sea to trade goods and slaves. Some historians believe that the Vikings are the ancestors of the Rus' - the earliest Russians.

It is interesting to note that this route from the Gulf of Finland to the lower Volga was established by Viking traders over 1,000 years earlier. The Vikings traveled regularly between Scandinavia and the Caspian Sea to trade goods and slaves. Some historians believe that the Vikings are the ancestors of the Rus' - the earliest Russians.

The days on the river must have seemed endless as they drifted mile after mile. The trip down the Volga was difficult, and large numbers of adults and children died along the way. The dead were taken to shore and quickly buried while relatives erected an improvised cross above the grave. Time was of the essence because they feared the groups of bandits hiding in the forests along the Volga. Of the Volga bandits, Karl Marx wrote in 1917:

The Volga over its whole immense expanse was the run of the “thieving Cossacks,” whose deeds were sung and who were not regarded among the people as common robbers in the ordinary sense, for they operated on a grand scale. In their own songs they say of themselves: “We are not thieves, not bandits — we are good brave fellows.”

Igor Pleve states that of the 26,676 people sent to settle in the Saratov region, 3,293 died en route, which is 12.3 percent of the total. (Note: Pleve's statistics exclude about 4,000 colonists not accounted for when his research was published).

Sometime in the summer of 1767, the transport group, which comprised the core that would settle in Norka, reached the river town of Saratov.

Saratov was established as a frontier fortress in 1590 by Tsar Feodor Ivanovich to maintain control of the Volga River and newly acquired territories. At the time, it was reportedly an unkempt, ramshackle town of about 10,000 residents in the province of Astrakhan.

Sometime in the summer of 1767, the transport group, which comprised the core that would settle in Norka, reached the river town of Saratov.

Saratov was established as a frontier fortress in 1590 by Tsar Feodor Ivanovich to maintain control of the Volga River and newly acquired territories. At the time, it was reportedly an unkempt, ramshackle town of about 10,000 residents in the province of Astrakhan.

On arrival in Saratov, the colonists were housed in 16 barracks, which were completed in November 1765 at the orders of Count Grigory Orlov. The colonists likely stayed in Saratov for at least a week, if not longer.

Before departing for their settlement area, the Saratov Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers (Kontora) provided each household with 25 rubles, a wagon, 21 feet of rope, two horses, a saddle, a harness, 35 feet of horse rein, and small tree trunks to be used for lumber. Many colonists also received one cow. The money, animals, supplies, and equipment were given to the colonists as a loan, and it was expected that the Russian government would be repaid.

After more than a year of arduous travel, the colonists began the final 50-mile overland trek to their designated settlement area along the Norka River, where they founded a new colony on August 15, 1767. Over the preceding year, many colonists died, and many children were born. For the survivors, a new life in Norka was about to begin.

Before departing for their settlement area, the Saratov Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers (Kontora) provided each household with 25 rubles, a wagon, 21 feet of rope, two horses, a saddle, a harness, 35 feet of horse rein, and small tree trunks to be used for lumber. Many colonists also received one cow. The money, animals, supplies, and equipment were given to the colonists as a loan, and it was expected that the Russian government would be repaid.

After more than a year of arduous travel, the colonists began the final 50-mile overland trek to their designated settlement area along the Norka River, where they founded a new colony on August 15, 1767. Over the preceding year, many colonists died, and many children were born. For the survivors, a new life in Norka was about to begin.

Sources

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb .: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2005. Print.

Idt, Andreas and Rauschenbach, Georg. Auswanderung deutsche Kolonisten nach Russland im Jahre 1766 (Second edition). Moscow: 2019.

Mai, Brent Alan. Transport of the Volga Germans from Oranienbaum to Colonies on the Volga 1766-1767. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1998. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Idt, Andreas and Rauschenbach, Georg. Auswanderung deutsche Kolonisten nach Russland im Jahre 1766 (Second edition). Moscow: 2019.

Mai, Brent Alan. Transport of the Volga Germans from Oranienbaum to Colonies on the Volga 1766-1767. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1998. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Last updated December 7, 2023