History > Revolution and Civil War

Revolution and Civil War 1917-1922

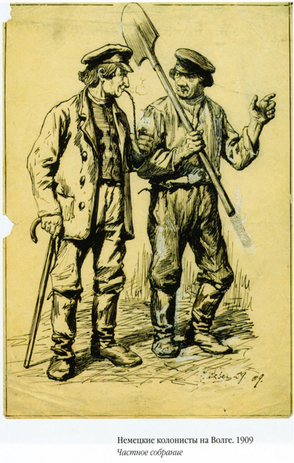

From 1904 to 1906, waves of mass political and social unrest spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. While limits were placed on the constitutional monarchy then, they were not satisfactory to many who continued their work to create more significant social and political change in Russia.

A successful Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917 resulted in the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II and the abolishment of private ownership of land and property. It changed forever the lives of the colonists in Norka.

Many Volga Germans were considered kulaks, a Soviet-defined category of relatively affluent and well-endowed farmers. According to Marxism-Leninism, kulaks were a class enemy of the poorer peasants. Many farmers and communists were killed, fields were burned, and many privately owned operations were destroyed. This often caused pronounced hunger and created significant problems in agriculture and the economy of the new Soviet Union.

All sides in the Russian Civil Wars of 1918-1920 — the Bolsheviks (Reds), the czarist Whites, the Anarchists, the seceding nationalities — had provisioned themselves by the ancient method of "living off the land" - they seized food from those who grew it, gave it to their armies and supporters, and denied it to their enemies. The Bolshevik government had requisitioned supplies from the peasantry for little or nothing in exchange. This led peasants to drastically reduce their crop production and contribute to a devastating famine.

Battles between the "Reds" and the "Whites" raged throughout the Volga region and arrived in Norka on April 17, 1918, when the wife of Heinrich Jäger became the first person to lose their life.

Patricia Hefflin (née Myers and a descendant of Elizabeth Weber) interviewed Mrs. Rudolph and Mrs. Spady, who lived in Norka during the Bolshevik Revolution. One afternoon at 4:00 pm, they were sitting outside having tea. Suddenly, they heard the sound of gunshots and bullets flying. The church bells began ringing, sounding an alarm to everyone in the colony. Both women fell to the ground for safety. They knew the alarm meant that the Bolsheviks were in Norka and would take what they wanted. They eventually made their way, along with their families, to hiding places dug under the houses. Here, they remained for three days. Those who had no place to hide would run down the streets to seek cover, and the Communists would shoot cannons down the streets, killing them. If captured, the Germans were forced to dig their own graves and were then shot. Eleven men were killed the first day the Bolsheviks entered Norka. While the people in the village were hiding, the Bolsheviks took food, grain, horses, cattle, and anything else of value. One of John Weber's nephews saw the Bolsheviks demanding wood, horses, soap, and other items from the Spady's. Mrs. Spady begged them to leave food and wood so they could eat. The Bolsheviks refused to leave anything, and some of the family later died from hunger.

Many Volga Germans were considered kulaks, a Soviet-defined category of relatively affluent and well-endowed farmers. According to Marxism-Leninism, kulaks were a class enemy of the poorer peasants. Many farmers and communists were killed, fields were burned, and many privately owned operations were destroyed. This often caused pronounced hunger and created significant problems in agriculture and the economy of the new Soviet Union.

All sides in the Russian Civil Wars of 1918-1920 — the Bolsheviks (Reds), the czarist Whites, the Anarchists, the seceding nationalities — had provisioned themselves by the ancient method of "living off the land" - they seized food from those who grew it, gave it to their armies and supporters, and denied it to their enemies. The Bolshevik government had requisitioned supplies from the peasantry for little or nothing in exchange. This led peasants to drastically reduce their crop production and contribute to a devastating famine.

Battles between the "Reds" and the "Whites" raged throughout the Volga region and arrived in Norka on April 17, 1918, when the wife of Heinrich Jäger became the first person to lose their life.

Patricia Hefflin (née Myers and a descendant of Elizabeth Weber) interviewed Mrs. Rudolph and Mrs. Spady, who lived in Norka during the Bolshevik Revolution. One afternoon at 4:00 pm, they were sitting outside having tea. Suddenly, they heard the sound of gunshots and bullets flying. The church bells began ringing, sounding an alarm to everyone in the colony. Both women fell to the ground for safety. They knew the alarm meant that the Bolsheviks were in Norka and would take what they wanted. They eventually made their way, along with their families, to hiding places dug under the houses. Here, they remained for three days. Those who had no place to hide would run down the streets to seek cover, and the Communists would shoot cannons down the streets, killing them. If captured, the Germans were forced to dig their own graves and were then shot. Eleven men were killed the first day the Bolsheviks entered Norka. While the people in the village were hiding, the Bolsheviks took food, grain, horses, cattle, and anything else of value. One of John Weber's nephews saw the Bolsheviks demanding wood, horses, soap, and other items from the Spady's. Mrs. Spady begged them to leave food and wood so they could eat. The Bolsheviks refused to leave anything, and some of the family later died from hunger.

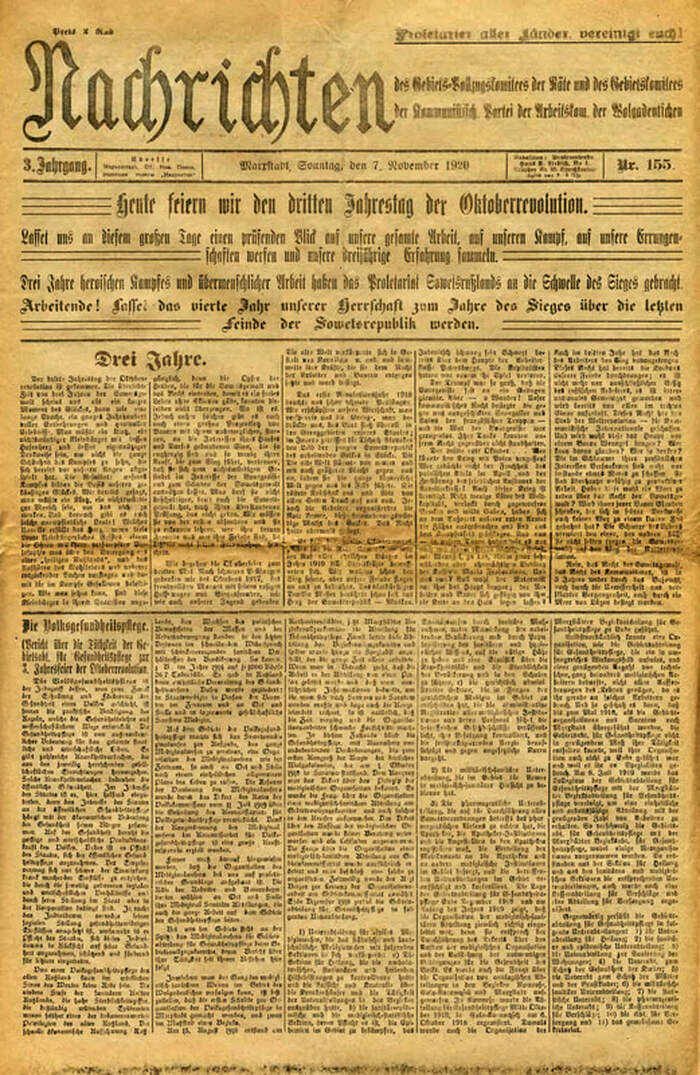

On February 28, 1918, in the colony of Warenburg, a congress of German representatives met. The delegates condemned the terror in German colonies by the Bolsheviks, the closure of the Saratower Deutsche Volkszeitung (Saratov German People's Newspaper), and the prosecution of activists involved with the German national movement. At the same time, under the stated "declaration of the rights of the people of Russia," delegates of this congress decided to petition the Soviet government to grant territorial autonomy to Germans of the Volga region.

On March 3, 1918, the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty with Germany was signed. Based on articles 21 and 22 of the Treaty, the Russian Germans could, within 10 years, return to their home country. Emigration to Germany took place in March and November 1918. Many business owners and wealthy colonists departed, fearing for their future under the Bolsheviks. More significant numbers of emigrants did not occur because of opposition from Soviet authorities.

While the war with Germany ended, the Civil War within Russia continued to rage for several years. In support of the White forces, the British bombed Red Army positions in the Summer of 1919 near the town of Kamyshin, which is approximately 90 miles southeast of Norka.

In January 1919, an uprising occurred against the Bolsheviks in the colonies of Warenburg and Balzer (near Norka). The conflict began over the requisitioning of food and property by the Red Army. While the resistance was initially successful, the Bolsheviks responded by sending troops to both villages, and 32 people involved in the uprising were killed, including the leaders. One of the Warenburg leaders was hung from the church bell tower for all to see.

On March 3, 1918, the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty with Germany was signed. Based on articles 21 and 22 of the Treaty, the Russian Germans could, within 10 years, return to their home country. Emigration to Germany took place in March and November 1918. Many business owners and wealthy colonists departed, fearing for their future under the Bolsheviks. More significant numbers of emigrants did not occur because of opposition from Soviet authorities.

While the war with Germany ended, the Civil War within Russia continued to rage for several years. In support of the White forces, the British bombed Red Army positions in the Summer of 1919 near the town of Kamyshin, which is approximately 90 miles southeast of Norka.

In January 1919, an uprising occurred against the Bolsheviks in the colonies of Warenburg and Balzer (near Norka). The conflict began over the requisitioning of food and property by the Red Army. While the resistance was initially successful, the Bolsheviks responded by sending troops to both villages, and 32 people involved in the uprising were killed, including the leaders. One of the Warenburg leaders was hung from the church bell tower for all to see.

Joanne Krieger provides the following excerpt from the story about her father's experience during the Russian Civil War:

My Dad, Johannes Grün (Green), was in the Russian army. I remember him telling about his travels to Turkey, Persia and other locations. He must have been in the reserves because he also managed the family store in the village. He eventually became an officer in the Russian army (White army). This promotion nearly cost him his life. In 1921 the Bolsheviks (Red army) rode into the village of Norka and fired at him. He jumped into a ditch, pretending to have been shot. The Bolshevik soldiers rode away thinking they had killed him. A short time later, my Dad (age 38 and single), his parents and younger brothers and sister emigrated from Russia leaving everything behind except for the clothes they were wearing, the family Bible and as much worthless money as they could sew into their clothes.

Sources

Herman, A. A. German Autonomy on the Volga, 1918-1941, Saratov: Saratov University, 1994.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown. 6-7.

Joanne Krieger, Portland, Oregon.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown. 6-7.

Joanne Krieger, Portland, Oregon.

Last updated December 7, 2023