History > World War I

World War I - 1914 to 1918

The year 1914 marked the sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) of the Volga German settlements in Russia. The group of approximately 30,000 colonists had grown to a population of over 600,000 and occupied about 25,000 square kilometers of land. Most of the population remained farmers, but some were engaged in industry. The sesquicentennial was celebrated with festivals that featured songs that retold the history of the Volga Germans and the values of their lifestyle, folklore, and culture.

On the eve of the First World War, Norka was a clean, crowded, and thriving town of around 14,000 people situated on heavily traveled roads. There were several lafki (general stores), four schools, a post office, a hospital, taverns, mills, grain storage buildings, and blacksmith shops. These secular signs of growth were subtle reflections of broader economic and social changes occurring in Russia.

On the eve of the First World War, Norka was a clean, crowded, and thriving town of around 14,000 people situated on heavily traveled roads. There were several lafki (general stores), four schools, a post office, a hospital, taverns, mills, grain storage buildings, and blacksmith shops. These secular signs of growth were subtle reflections of broader economic and social changes occurring in Russia.

The outbreak of World War I on July 28, 1914, was met with anxiety and fear by the Volga German colonists. The war exacerbated Russia’s Germanophobia and Slavophile tendencies. Foreign Minister Sazonov called for a “final solution” to the ethnic German problem in Russia, noting that the time had come "...to deal with this long over-due problem, for the current war has created the conditions to make it possible to solve this problem once and for all.” Russian General Polivanov wrote in a pamphlet that was distributed among Russian soldiers on the order of Grand Duke Nicholas, the Tsar's uncle:

"Russia's Germans must all be driven out, without respect of age, sex, any supposed usefulness, or their many years of residence in the empire."

Despite the anti-German sentiments, tens of thousands of Volga Germans served honorably in the Russian military. Regardless of their loyalty to Russia, where their families had lived for over 150 years, the following insult was not uncommon:

"You are Germans—Nyemtzy," they were charged. We are going to fight the barbarians, your brothers. Woe to you, you scoundrels, if you make any effort to help your Kaiser Wilhelm."

Pogroms against Germans living in St. Petersburg (renamed Petrograd) began on August 4, 1914, with German shops and businesses destroyed. The pogroms spread to Moscow on May 27, 1915. For three days, crowds damaged businesses and homes owned by anyone with a German name.

German colonists serving in the military were not allowed to speak German or sing German songs, and they were watched as if they were the enemy. The worst came in 1915 after the Germans' major defeat of the Russian army. The ethnic Germans serving in the Russian military were conveniently blamed for the defeat.

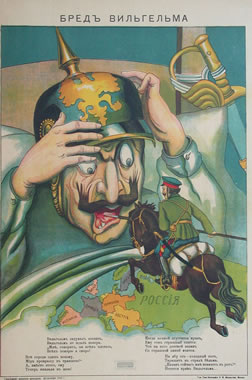

War hysteria was being spread by vilifying publications and rumors. Russia's semi-literate and non-literate millions had no way of ascertaining the facts and readily accepted the absurd propaganda. For example, it was claimed that a Volga German flour mill magnate was shipping a weekly trainload of flour from Saratov to Riga for Kaiser Wilhelm's forces. None of the credulous asked or explained how a trainload of food could be shipped across a war front manned its entire length by Russian troops. Despite the wild rumors, no known cases exist of a German colonist being charged with treason or sabotage.

The German language was banned from use in public, in schools, on the streets, or in the press. German language newspapers in Russia were suppressed, and some pastors of German origin were sent to Siberia. The only public use of German that was allowed was the reading of Bible passages during church services.

The war shut off nearly all emigration from Norka and the Volga German colonies. Those who remained would live through very difficult times.

In May 1916, Jacob Weidenkeller wrote to his brother Wilhelm in Canada about the war and its impact on Norka:

War hysteria was being spread by vilifying publications and rumors. Russia's semi-literate and non-literate millions had no way of ascertaining the facts and readily accepted the absurd propaganda. For example, it was claimed that a Volga German flour mill magnate was shipping a weekly trainload of flour from Saratov to Riga for Kaiser Wilhelm's forces. None of the credulous asked or explained how a trainload of food could be shipped across a war front manned its entire length by Russian troops. Despite the wild rumors, no known cases exist of a German colonist being charged with treason or sabotage.

The German language was banned from use in public, in schools, on the streets, or in the press. German language newspapers in Russia were suppressed, and some pastors of German origin were sent to Siberia. The only public use of German that was allowed was the reading of Bible passages during church services.

The war shut off nearly all emigration from Norka and the Volga German colonies. Those who remained would live through very difficult times.

In May 1916, Jacob Weidenkeller wrote to his brother Wilhelm in Canada about the war and its impact on Norka:

It is a difficult time in this world now: tribulation and hardship for everyone who is standing in front of the fire in the war and also for us who are at home and have to expect bad news from the theater of war. When it is said that this and that fell, that and the other is a cripple for life, that's a difficult thing. This evil war has already swept away many of our brothers. Where there are many bullets flying and one has death constantly before one's eyes, there are many dead and many more cripples and lame. But what can you do? Once you swear to fight for the country, you have to do it. Peace is written in the newspaper, but you can't always refer to it. I'm still at home, but who knows how it will be until you write again. The soldiers are still enough... There are still workers because there are many Polish, Russian, and German prisoners of war in the village, more than 600 in number. So there is no shortage of workers. But they are all strangers.

Ironically, despite anti-German sentiment in the United States, men who had emigrated from Norka (and their descendants) served in the U.S. military during World War I. They fought against Imperial Germany and her allies.

Charlie Bauer is seated in the center of the front row of this group of U.S. soldiers who served in World War I. Charlie was the son of Heinrich and Katherine Bauer from Norka and was born in Oregon in 1895. This photograph was taken in Trier, Germany in 1917 and was provided courtesy of Kris Dillman.

With the February 1917 revolution and the abdication of Tsar Nicholas on March 15. In 1917, a Provisional Government established a democratically elected assembly. In response, over 300 district representatives from the Volga German colonies met in Saratov from April 25 to 27, 1917, to discuss the German people's needs and elect representatives from each district to represent them in a newly formed Russian Constituent Assembly. Representing the district of Norka at this meeting were Pastor Friedrich Wacker, J. Schlidt, G. Schultz, P. Weber, K. Weber, P. Krüger, and A. Sauer. Norka native Pastor Johannes Schleuning represented the Moscow German Congress at the meeting. Although the October 1917 overthrow of the Provisional Government by the Bolsheviks changed the intended role of the Volga German assembly, it would nevertheless become a model for the establishment of the Autonomous Volga German Republic under the new Soviet regime.

The war created an extreme anti-German sentiment in Russia. Approximately 190,000 to 200,000 ethnic Germans living in Russia were deported to Siberia from 1915 to 1916. The number of losses is unknown, but a mortality rate of one-third to one-half (63,000-100,000) is estimated.

In 1916, an order was issued to deport around 650,000 Volga Germans to the east (Siberia) as well, but the February 1917 revolution prevented the deportation from being carried out. For a time, most Volga Germans welcomed the new Provisional government. Peter Sinner wrote the following about the rapidly changing nature of these events:

The war created an extreme anti-German sentiment in Russia. Approximately 190,000 to 200,000 ethnic Germans living in Russia were deported to Siberia from 1915 to 1916. The number of losses is unknown, but a mortality rate of one-third to one-half (63,000-100,000) is estimated.

In 1916, an order was issued to deport around 650,000 Volga Germans to the east (Siberia) as well, but the February 1917 revolution prevented the deportation from being carried out. For a time, most Volga Germans welcomed the new Provisional government. Peter Sinner wrote the following about the rapidly changing nature of these events:

When the storm had subsided, our German colonists saw themselves betrayed once more. The temporary government halted right away the fierce law of expulsion, but they did not rescind it. The general quartermaster of the temporary government renewed the prohibition of the German language. The war was to be continued, too.

There was no safe harbor for the Volga Germans, and the devastating impacts of the Revolution, Civil War, Bolshevism, famine, and deportation were close at hand.

Sources

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 192-94. Print. <https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=rzJh_whDGmIC>

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 14-15. Print.

Sinner, Peter. Germans in the Land of the Volga. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1989. Print.

Sinner, Samuel D. "The German-Russian Genocide: Remembrance in the 21st Century." Germans from Russia Heritage Collection. Web. 26 Aug. 2016. <https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/research/scholarly/meetings_conventions/dr_sinner.html>.

Walters, George J. Wir Wollen Deutsche Bleiben (We Want to Remain German): The Story of the Volga Germans. Kansas City, MO: Halcyon House, 1982. Print.

Versammlung der Kreisbevollmächtigten der Wolgakolonien in Saratow. Geschichte der Wolgadeutschen website accessed December 19, 2016.

Letter from Jacob Weidenkeller to Wilhelm Weidenkeller. Published in Die Welt-Post on August 17, 1916.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 14-15. Print.

Sinner, Peter. Germans in the Land of the Volga. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1989. Print.

Sinner, Samuel D. "The German-Russian Genocide: Remembrance in the 21st Century." Germans from Russia Heritage Collection. Web. 26 Aug. 2016. <https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/research/scholarly/meetings_conventions/dr_sinner.html>.

Walters, George J. Wir Wollen Deutsche Bleiben (We Want to Remain German): The Story of the Volga Germans. Kansas City, MO: Halcyon House, 1982. Print.

Versammlung der Kreisbevollmächtigten der Wolgakolonien in Saratow. Geschichte der Wolgadeutschen website accessed December 19, 2016.

Letter from Jacob Weidenkeller to Wilhelm Weidenkeller. Published in Die Welt-Post on August 17, 1916.

Last updated December 4, 2023