Community > Cottage Industries

Cottage Industries and Local Businesses

Although many of the residents of Norka engaged in agriculture and the associated milling business, some made their living through other small-scale commercial practices.

The colonists brought many trades and skills learned and practiced in their German homelands. The ship arrival records from 1766 and the 1767 census show the following occupations were practiced by settlers in Norka: farmer, teacher, bookbinder, stonemason, wheelwright, tailor, weaver, shoemaker, and stocking maker. Many other settlers were simply listed as craftsmen.

Germany had a long tradition of guilds, which originated in the 12th century. Guilds operated on a system where a young man first worked as an apprentice, learning the basic skills of the trade. After the apprentice attained a certain level of knowledge and skill, he was promoted to journeyman. At this time, he was allowed to travel the land in search of masters in his field for whom he could work and from whom he could learn the requisite skills to become a master himself. When he completed his journeyman time with appropriate skill and knowledge, he would be promoted to master. This important step allowed him to set up his own shop. The Russian recruiters recognized the value of the skills learned by members of the guild system and the benefits they would bring to the development of the new colonies on the lower Volga.

The colonists brought many trades and skills learned and practiced in their German homelands. The ship arrival records from 1766 and the 1767 census show the following occupations were practiced by settlers in Norka: farmer, teacher, bookbinder, stonemason, wheelwright, tailor, weaver, shoemaker, and stocking maker. Many other settlers were simply listed as craftsmen.

Germany had a long tradition of guilds, which originated in the 12th century. Guilds operated on a system where a young man first worked as an apprentice, learning the basic skills of the trade. After the apprentice attained a certain level of knowledge and skill, he was promoted to journeyman. At this time, he was allowed to travel the land in search of masters in his field for whom he could work and from whom he could learn the requisite skills to become a master himself. When he completed his journeyman time with appropriate skill and knowledge, he would be promoted to master. This important step allowed him to set up his own shop. The Russian recruiters recognized the value of the skills learned by members of the guild system and the benefits they would bring to the development of the new colonies on the lower Volga.

At the time the 1775 census was taken, living in the colony were blacksmiths, a cooper, silk weavers, a camlet weavers, mill operators, a tailor, a shoemaker, a watchmaker, and a wheelwright. The 1798 census notes the existence of two mills, three blacksmith shops, and four shoemakers.

The Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers (Kontora) had a vested interest in promoting the trades. On September 16, 1800, the Kontora published a document titled “Instruction Regarding Interior Order and Administration in the Volga Colonies.” The Instruction prescribed the following: “In each colony, for various efforts and public purposes, there is to be a blacksmith so that everyone has the appropriate material needed to do the work ordered of him.” The Kontora demanded not only that special permission be obtained for performing trade occupations, but also facilitated the small trades in every possible way, “so that no resident enters into a state of idleness… and that the women are also busy with spinning of wool, flax and with weaving of linen and cloth, with maintaining poultry, making butter, and similar activities.” Additionally, the Instruction recommended that the leaders in the colonies “take care that producers do not charge excessive and immoderate prices for their goods, and that they should be satisfied with prices acceptable to the community.” Community leaders, according to regulations from the Kontora, must “keep records, including lists of idlers… so that the diligent and honest residents might enjoy more trust, while the idlers are shown that a good opinion cannot be had of them nor be able to expect any advantages, and in addition, village authorities… should punish them with monetary penalties or feed them only bread and water, or force them to work, and to give them a specific task.”

Various crafts and skills were needed for the colony to survive and thrive. While many of these skilled workers provided materials for the local population, certain products were marketed outside Norka over time.

Two men from Norka, J. Deines and W. Spady, manufactured Sarpinka (a cotton cloth), which they displayed at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, England. The Sarpinka business employed many people in Norka.

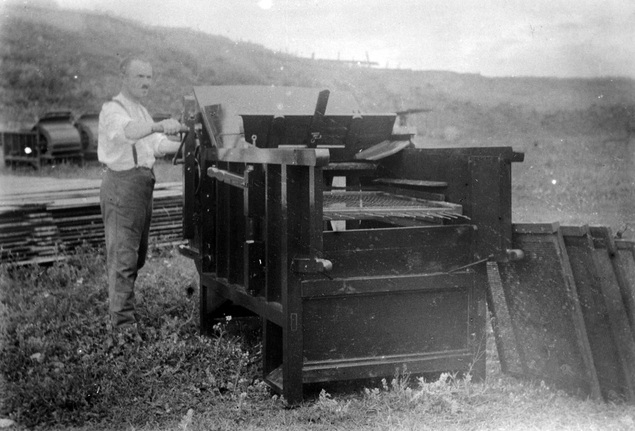

Beginning in the 1880s, winnowing machines, or Putzmaschines as the colonists called them, were also manufactured in Norka. The Volga German winnowing machines became so well known that the term "kolonist" was commonly used to describe the machines. Kolonist was often branded onto the side of the machine to improve its marketability.

Many businesses relied on the port colony of Schilling, which had sawmills, hotels, grain elevators, flour mills, restaurants, and barge facilities for transporting goods on the Volga River. Balzer was another important commercial town where spinning and weaving products were predominant.

The Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers (Kontora) had a vested interest in promoting the trades. On September 16, 1800, the Kontora published a document titled “Instruction Regarding Interior Order and Administration in the Volga Colonies.” The Instruction prescribed the following: “In each colony, for various efforts and public purposes, there is to be a blacksmith so that everyone has the appropriate material needed to do the work ordered of him.” The Kontora demanded not only that special permission be obtained for performing trade occupations, but also facilitated the small trades in every possible way, “so that no resident enters into a state of idleness… and that the women are also busy with spinning of wool, flax and with weaving of linen and cloth, with maintaining poultry, making butter, and similar activities.” Additionally, the Instruction recommended that the leaders in the colonies “take care that producers do not charge excessive and immoderate prices for their goods, and that they should be satisfied with prices acceptable to the community.” Community leaders, according to regulations from the Kontora, must “keep records, including lists of idlers… so that the diligent and honest residents might enjoy more trust, while the idlers are shown that a good opinion cannot be had of them nor be able to expect any advantages, and in addition, village authorities… should punish them with monetary penalties or feed them only bread and water, or force them to work, and to give them a specific task.”

Various crafts and skills were needed for the colony to survive and thrive. While many of these skilled workers provided materials for the local population, certain products were marketed outside Norka over time.

Two men from Norka, J. Deines and W. Spady, manufactured Sarpinka (a cotton cloth), which they displayed at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, England. The Sarpinka business employed many people in Norka.

Beginning in the 1880s, winnowing machines, or Putzmaschines as the colonists called them, were also manufactured in Norka. The Volga German winnowing machines became so well known that the term "kolonist" was commonly used to describe the machines. Kolonist was often branded onto the side of the machine to improve its marketability.

Many businesses relied on the port colony of Schilling, which had sawmills, hotels, grain elevators, flour mills, restaurants, and barge facilities for transporting goods on the Volga River. Balzer was another important commercial town where spinning and weaving products were predominant.

Conrad Brill mentions the distinction between farming and other occupations in his story titled Memories of Norka:

Most of the villagers were farmers . . . almost every village had a supply of blacksmiths, wagon makers, shoemakers, carpenters, and various other laboring people who weren't interested in farming for themselves, or may have used the farming for a part of their livelihood, along with a trade. There were actually people, who sold their "dusch" (share of farmland) to people for cash, or had it farmed for shares and they did work for others.

Brill's brother-in-law was part of the Reiche (rich) Schleuning family. Alexander Schleuning (born in 1899, died in 1941) was reportedly the son of one of the wealthiest men in Norka in the early 1900s. In addition to farming his extensive land holdings with 25 teams of horses, he also owned a mill, the Lafka (a general store), orchards, and vegetable gardens. Alexander married Olga (Olinde) Schreiber. They were deported to Siberia in 1941, and Alexander died there that same year.

Heinrich Liehl (also Lehl) was nicknamed Rote Schintler, meaning he was a redheaded and a coat maker. Lehl was known throughout most villages as one of the best leather coat makers in the colonies. Heinrich would be called to the best homes, where he stayed until he finished making the great coats for all family members, receiving free room and board, plus good wages for his work.

Johannes Pauli (also Pauly) owned a brick-making factory along the roadway of the Norka Grava (ravine). Bricks were made of materials on the site and were mixed by two large paddles connected to a merry-go-round affair built into a round tank about 16 feet in diameter and pulled by a horse. The brick mix was poured into brick forms, sun-dried until hard enough to handle without breaking, then placed into racks in open silo-type bunkers about sixteen feet wide and eight feet deep. They stretched in length about a city block. There were several bunkers of this size, and they burned up a lot of waste in the baking process. When they were in the bunkers and ready to bake, the men piled any burnable materials into the pit and set it afire. After the bricks were correctly baked, they were so hard it took a hacksaw-type saw to cut one in half. After baking, they were stacked in neat rows along the roadway for sale. The rows of bricks stretched for blocks. Johannes Pauli was born May 25, 1861, and married Katharina Christina Schwindt on February 8, 1883. She was born in Norka on July 25, 1863.

Julla Spady was the son of a successful doctor who died and left a large sum of silver coins to his heirs. With this capital, Julla opened a mercantile store in Norka. Merchandise to stock the store shelves was unloaded from barges in the port colony of Schilling. Conrad Brill recalls hauling seven wagon loads from the barges to Norka, including "everything from toothpicks to farm implements."

Conrad Brill also shows a Schleicher Mercantile on his 1920s map of Norka.

Heinrich Liehl (also Lehl) was nicknamed Rote Schintler, meaning he was a redheaded and a coat maker. Lehl was known throughout most villages as one of the best leather coat makers in the colonies. Heinrich would be called to the best homes, where he stayed until he finished making the great coats for all family members, receiving free room and board, plus good wages for his work.

Johannes Pauli (also Pauly) owned a brick-making factory along the roadway of the Norka Grava (ravine). Bricks were made of materials on the site and were mixed by two large paddles connected to a merry-go-round affair built into a round tank about 16 feet in diameter and pulled by a horse. The brick mix was poured into brick forms, sun-dried until hard enough to handle without breaking, then placed into racks in open silo-type bunkers about sixteen feet wide and eight feet deep. They stretched in length about a city block. There were several bunkers of this size, and they burned up a lot of waste in the baking process. When they were in the bunkers and ready to bake, the men piled any burnable materials into the pit and set it afire. After the bricks were correctly baked, they were so hard it took a hacksaw-type saw to cut one in half. After baking, they were stacked in neat rows along the roadway for sale. The rows of bricks stretched for blocks. Johannes Pauli was born May 25, 1861, and married Katharina Christina Schwindt on February 8, 1883. She was born in Norka on July 25, 1863.

Julla Spady was the son of a successful doctor who died and left a large sum of silver coins to his heirs. With this capital, Julla opened a mercantile store in Norka. Merchandise to stock the store shelves was unloaded from barges in the port colony of Schilling. Conrad Brill recalls hauling seven wagon loads from the barges to Norka, including "everything from toothpicks to farm implements."

Conrad Brill also shows a Schleicher Mercantile on his 1920s map of Norka.

Brill states that a man with the Spitzname (nickname) of Schneider Hahn operated a tailoring shop, and another man called Gerver (tanner) Faigler ran a local tannery. Faigler was a significant employer, and at different times of the year, he hired as many men as the owner of the largest flour mill. Mr. Faigler was considered a generous employer who gave his employees schnapps breaks and a hearty noon meal. Faigler is a phonetic spelling of the surname Vögler. The "Gerver Faigler" was Johannes Vögler, born 22 June 1832 in Norka.

Brill tells another story of a man named Schwartz who went to America and returned to Norka with "a bundle of money," which he used to start a mercantile store. Although he had made a lot of money in America, he reportedly didn't like that it was "a woman's world."

An 1859 Central Statistical Committee Report shows that there were 483 properties, 5 leather businesses, 3 oil mills, and 21 mills of other types.

By 1886, over 50 percent of the adult males living in Norka worked in non-farming trades and crafts. There were a reported 54 trade enterprises, which included 6 windmills, 6 oil mills, 5 leather tanners, 6 carpentries, 11 shoemakers, 5 tailor shops, 11 blacksmith shops, 5 taverns, 13 stores (3 for textiles, 6 general merchandise stores, 4 wine shops). About 300 people worked as teamsters hauling freight. There were 78 wagon builders, 39 blacksmiths, 36 weavers, 28 furniture makers, 25 shoemakers, 20 shepherds, 19 millers, 19 tailors, 16 leather workers, 14 carpenters, 10 saddle makers, 9 sheep skin tanners, 7 carpenters, 6 masons, 3 bookbinders, and 1 locksmith. Many of these people employed others in their operation.

In 1898, A. N. Minkh reported that there were 54 enterprises in Norka, including 6 windmills for grain, 6 oil mills, 5 tanneries, 7 joineries, 11 shoemaker shops, 5 tailoring shops, 11 blacksmith shops, 11 stores (lafka) and 5 taverns. Minkh also reports that by 1887 about 547 people were engaged in various trades, including: 89 hired men, 2 coopers, 13 fullers, 6 bricklayers, 16 tanners, 39 blacksmiths, 78 wheel-wrights, 19 millers, 9 (sheepskin) fur-dressers, 20 shepherds, 2 bookbinders, 7 sawyers, 14 carpenters, 19 tailors, 25 shoemakers, 1 locksmith, 28 joiners, 6 watchmen, 36 weavers, 28 traders, and 10 saddle-makers. Among trade and manufacturing enterprises owned by the settlers, 3 stores sold manufactured produce, 6 stores sold trifles, and 4 stores sold wine.

Those who emigrated often took their entrepreneurial skills to the New World. Ludwig Deines operated a hauling business using sleds to transport goods during the cold winter months. Ludwig immigrated to the United States, where he settled in Portland, Oregon. In Portland, he used the skills he learned in Russia to start a garbage collection service, which became very successful over time. Johannes Pauli's son, John, immigrated to the United States in 1907 and operated a successful business in Portland, Oregon.

By the time of the First World War (1914), there were 24 business enterprises and 14 shops and trading houses in Norka. Norka also boasted its own savings and loan organization.

Brill tells another story of a man named Schwartz who went to America and returned to Norka with "a bundle of money," which he used to start a mercantile store. Although he had made a lot of money in America, he reportedly didn't like that it was "a woman's world."

An 1859 Central Statistical Committee Report shows that there were 483 properties, 5 leather businesses, 3 oil mills, and 21 mills of other types.

By 1886, over 50 percent of the adult males living in Norka worked in non-farming trades and crafts. There were a reported 54 trade enterprises, which included 6 windmills, 6 oil mills, 5 leather tanners, 6 carpentries, 11 shoemakers, 5 tailor shops, 11 blacksmith shops, 5 taverns, 13 stores (3 for textiles, 6 general merchandise stores, 4 wine shops). About 300 people worked as teamsters hauling freight. There were 78 wagon builders, 39 blacksmiths, 36 weavers, 28 furniture makers, 25 shoemakers, 20 shepherds, 19 millers, 19 tailors, 16 leather workers, 14 carpenters, 10 saddle makers, 9 sheep skin tanners, 7 carpenters, 6 masons, 3 bookbinders, and 1 locksmith. Many of these people employed others in their operation.

In 1898, A. N. Minkh reported that there were 54 enterprises in Norka, including 6 windmills for grain, 6 oil mills, 5 tanneries, 7 joineries, 11 shoemaker shops, 5 tailoring shops, 11 blacksmith shops, 11 stores (lafka) and 5 taverns. Minkh also reports that by 1887 about 547 people were engaged in various trades, including: 89 hired men, 2 coopers, 13 fullers, 6 bricklayers, 16 tanners, 39 blacksmiths, 78 wheel-wrights, 19 millers, 9 (sheepskin) fur-dressers, 20 shepherds, 2 bookbinders, 7 sawyers, 14 carpenters, 19 tailors, 25 shoemakers, 1 locksmith, 28 joiners, 6 watchmen, 36 weavers, 28 traders, and 10 saddle-makers. Among trade and manufacturing enterprises owned by the settlers, 3 stores sold manufactured produce, 6 stores sold trifles, and 4 stores sold wine.

Those who emigrated often took their entrepreneurial skills to the New World. Ludwig Deines operated a hauling business using sleds to transport goods during the cold winter months. Ludwig immigrated to the United States, where he settled in Portland, Oregon. In Portland, he used the skills he learned in Russia to start a garbage collection service, which became very successful over time. Johannes Pauli's son, John, immigrated to the United States in 1907 and operated a successful business in Portland, Oregon.

By the time of the First World War (1914), there were 24 business enterprises and 14 shops and trading houses in Norka. Norka also boasted its own savings and loan organization.

Sources

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 68,151. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan. 1798 Census of the German Colonies along the Volga: Economy, Population, and Agriculture. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1999. Print.

Minkh, A. N. History and Geographic Dictionary of Saratov Province. Saratov, 1898. pp. 688-691.

Mertens, Ulrich, Allyn Brosz, Alex Herzog, and Thomas Stangl. German-Russian Handbook: A Reference Book for Russian German and German Russian History and Culture with Place Listings of Former German Settlement Areas. Fargo, ND: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State U Libraries, 2010. Print.

Official Catalogue of the Industrial Department (from the 1862 International Exhibition in London, England). United Kingdom: Cambridge UK, 1862. Print. p. 380.

Orlov, Grigory Grigoryevich, Report of Conditions of Settlements on the Volga to Catherine II, February 14, 1769. Translation courtesy of Bill Pickelhaupt.

PSSRI. Coll. 1, volume XXVI. St. Petersburg, 1832. Pp. 299-313.

Text taken from: Vospominanya o Norke // Der Bote / Vestnik. 2000. Number 1. P. 27.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 68,151. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan. 1798 Census of the German Colonies along the Volga: Economy, Population, and Agriculture. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1999. Print.

Minkh, A. N. History and Geographic Dictionary of Saratov Province. Saratov, 1898. pp. 688-691.

Mertens, Ulrich, Allyn Brosz, Alex Herzog, and Thomas Stangl. German-Russian Handbook: A Reference Book for Russian German and German Russian History and Culture with Place Listings of Former German Settlement Areas. Fargo, ND: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State U Libraries, 2010. Print.

Official Catalogue of the Industrial Department (from the 1862 International Exhibition in London, England). United Kingdom: Cambridge UK, 1862. Print. p. 380.

Orlov, Grigory Grigoryevich, Report of Conditions of Settlements on the Volga to Catherine II, February 14, 1769. Translation courtesy of Bill Pickelhaupt.

PSSRI. Coll. 1, volume XXVI. St. Petersburg, 1832. Pp. 299-313.

Text taken from: Vospominanya o Norke // Der Bote / Vestnik. 2000. Number 1. P. 27.

Last updated November 26, 2023