Religion > Church Buildings

The Three Churches of Norka

The first parochial school in Norka, built in 1771, also served as a prayer house in the early years of settlement. A separate church building would soon follow.

Russian survey teams responsible for planning each new colony determined the location of the first church building in Norka.

The first church building was very likely a simple wooden structure that served the needs of roughly 750 people living in the colony at that time. It was the largest and best building in the village and was undoubtedly the proud centerpiece of the colony. Under the leadership of Rev. Johannes Baptista Cattaneo, the Norka congregation purchased its first organ in 1791. The organ was previously used in a chapel within Castle Barby, Germany, where Rev. Cattaneo had stopped to visit on his initial journey to Norka. Norka proudly claimed to have been among the first German colonies to possess such a fine instrument. The first church served the colony for over 50 years. Wear due to age, use, weather, and a growing population created a need for a new and larger building.

The second parsonage was built in 1803, likely replacing a simple structure from the early days of settlement.

In 1822, Rev. Cattaneo led the building of the second church, which was constructed on the site of the first church. The community took on all the planning, funding, and construction responsibilities. Government help was not provided. The new and larger church was consecrated the same year by Rev. Johann Samuel Huber, Provost of the Bergseite Reformed congregations and senior assistant to the Saratov Consistory. It is likely that this church also had a very unassuming appearance, which was common before the era of the Kontor style of architecture that developed in the late 1800's. Most churches at this time were unpretentious fir wood structures with small windows and a steeple crowned by a dome in the form of an onion. Over time, all of these churches disappeared from the horizon. The second church stood until 1880, when construction of the third church began.

Russian survey teams responsible for planning each new colony determined the location of the first church building in Norka.

The first church building was very likely a simple wooden structure that served the needs of roughly 750 people living in the colony at that time. It was the largest and best building in the village and was undoubtedly the proud centerpiece of the colony. Under the leadership of Rev. Johannes Baptista Cattaneo, the Norka congregation purchased its first organ in 1791. The organ was previously used in a chapel within Castle Barby, Germany, where Rev. Cattaneo had stopped to visit on his initial journey to Norka. Norka proudly claimed to have been among the first German colonies to possess such a fine instrument. The first church served the colony for over 50 years. Wear due to age, use, weather, and a growing population created a need for a new and larger building.

The second parsonage was built in 1803, likely replacing a simple structure from the early days of settlement.

In 1822, Rev. Cattaneo led the building of the second church, which was constructed on the site of the first church. The community took on all the planning, funding, and construction responsibilities. Government help was not provided. The new and larger church was consecrated the same year by Rev. Johann Samuel Huber, Provost of the Bergseite Reformed congregations and senior assistant to the Saratov Consistory. It is likely that this church also had a very unassuming appearance, which was common before the era of the Kontor style of architecture that developed in the late 1800's. Most churches at this time were unpretentious fir wood structures with small windows and a steeple crowned by a dome in the form of an onion. Over time, all of these churches disappeared from the horizon. The second church stood until 1880, when construction of the third church began.

The first foundation stone of the third church was laid on June 2, 1880. A formal dedication ceremony was performed on June 24, 1880. The ceremony was led by the Rev. Samuel Bonwetsch from Dorpat (the son of Norka pastor Christoph Heinrich Bonwetsch), who spoke to the importance of Christian foundations reading from 1 Peter 3: 4-5. Following Rev. Bonwetsch, Norka's Rev. Wilhelm Stärkel spoke and read from Psalm 5. Rev. Gottlieb Friedrich Jordan, from the colony of Balzer, closed with a heartfelt prayer of thanks.

The following church officials were present when the cornerstone was laid: H. Georg Gerlach, Heinrich Yost, H. Georg Scheidemann, Johannes Krieger, and Johannes Deines. Also present were village officials: Heinrich Schlitt (Superintendent of the Village Council), Heinrich Peter Sinner (Village Assessor), Conrad Batz (District Secretary), Johannes Schmer (Village Mayor), Johann Georg Batz (Village Council Secretary), Adam Rudolf (Schoolmaster and Deacon), J. P. Deines (Deacon), Johann Rudolf (Deacon), and Johann Heinrich Deines (Secretary).

The following church officials were present when the cornerstone was laid: H. Georg Gerlach, Heinrich Yost, H. Georg Scheidemann, Johannes Krieger, and Johannes Deines. Also present were village officials: Heinrich Schlitt (Superintendent of the Village Council), Heinrich Peter Sinner (Village Assessor), Conrad Batz (District Secretary), Johannes Schmer (Village Mayor), Johann Georg Batz (Village Council Secretary), Adam Rudolf (Schoolmaster and Deacon), J. P. Deines (Deacon), Johann Rudolf (Deacon), and Johann Heinrich Deines (Secretary).

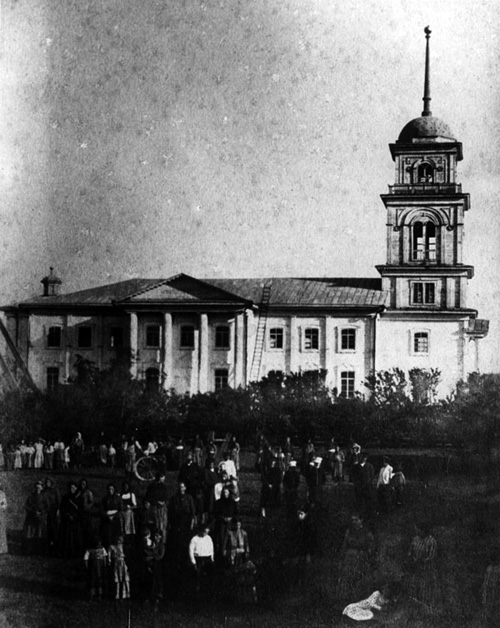

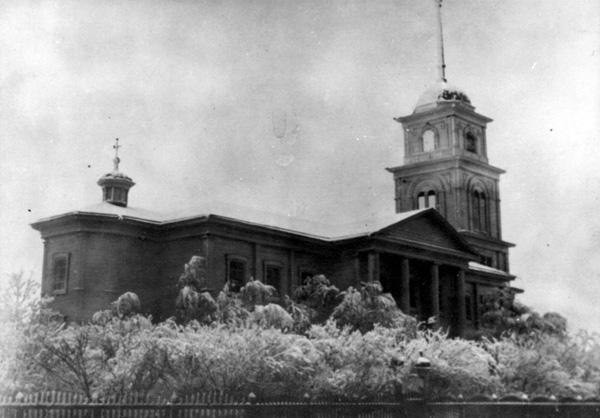

The church was in the middle of the colony between 8th and 9th streets. It was built primarily from wood in the Kontor style architectural style. The neoclassic style was named with a somewhat derogatory reference to the Kontora (the Saratov Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers), who imposed the Russian classicism architecture on the colonists. In the 19th century, most churches were designed by professional architects, and the plans for some of the Volga German churches are held in the Russian archives (the Norka church plan has not been found).

Kontor-style churches typically included an elongated building featuring four to six exterior columns on the short and long sides, which rested upon a common foundation and substructure. Most churches had a tiered "wedding cake" steeple. The high, slender steeple, usually two to three stories tall, was topped off with a hemisphere and an elevated mast pointing heavenward. The interior was typically a columned hall with a second-floor balcony. This specific architectural style distinguished the Kontor-style churches from Russian Orthodox houses of worship.

Churches of this era were generally constructed of wood (some were stone or brick) and had walls for friezes but typically lacked this decoration. There was a gable-end in the form of a flat triangle on which some space was set aside for a larger sculptured frieze, but the Norka church lacked this feature, and there is a strongly protruding gable-end cornice.

Kontor-style churches typically included an elongated building featuring four to six exterior columns on the short and long sides, which rested upon a common foundation and substructure. Most churches had a tiered "wedding cake" steeple. The high, slender steeple, usually two to three stories tall, was topped off with a hemisphere and an elevated mast pointing heavenward. The interior was typically a columned hall with a second-floor balcony. This specific architectural style distinguished the Kontor-style churches from Russian Orthodox houses of worship.

Churches of this era were generally constructed of wood (some were stone or brick) and had walls for friezes but typically lacked this decoration. There was a gable-end in the form of a flat triangle on which some space was set aside for a larger sculptured frieze, but the Norka church lacked this feature, and there is a strongly protruding gable-end cornice.

According to Reuben Bauer in his book One of Many, the foundations of the third church were approximately three feet thick and constructed from stone and mortar. The dimensions were 127 feet wide and 175 feet long. Each side of the church had 20 windows and four exterior pillars. There were three doors besides the main door where the faithful would enter. The main entry into the narthex was also framed by pillars. The timber frame gable roof was covered with tin sheeting. Crowning the four-tiered domed steeple of the church was a large iron globe, approximately 5 feet in diameter, which symbolized the world. Above the hollow globe was a six-foot gilt cross. Conrad Brill recalls that the cross was built of heavy sheet metal by a man from the colony of Anton. The cross was brought to Norka on a large wagon. It was then painted before it was raised by block and cable to the steeple and fitted in a slot built into the peak. The cross was dedicated on October 6, 1880, by Pastor Stärkel, who read Corinthians 1:1-10, and Pastor Wietmehr, who read John 3:14.

The timber used to build the church was cut in the timber lands to the north, and the logs were assembled into a raft. The suppliers navigated the raft down the Volga River to the port colony of Schilling, where there was a sawmill. The bark was removed from the logs, and some were sawn into boards and timbers. The lumber was then hauled from Schilling on three interconnected wagons. Many of the long poles brought from Schilling were placed in a cradle and sawn in half. The round side of the pole was positioned to the interior of the building, and the flat side faced outward.

Men from the colony supplied the labor to build the church. Johannes Krieger, a church deacon and one of the Volga German scouts sent to America in 1874, oversaw the construction work. Few mechanical devices were used in the construction. As a result, it took over three and one-half years to complete the building.

The exterior wooden plank siding of the church was painted white. On a clear day, the church could be seen from many miles away.

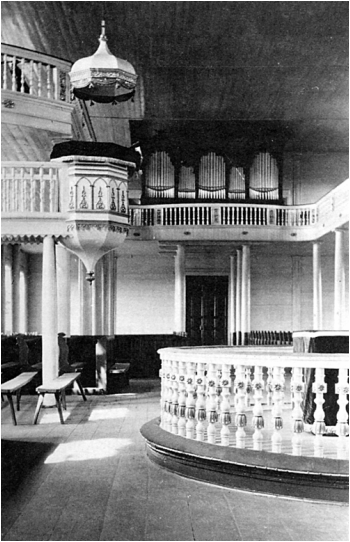

The church's interior was simple in design and separated into three areas: the narthex, the nave, and the altar. The walls and ceiling were painted but largely unadorned in keeping with the beliefs of the Reformed church. Looking down the wood plank floor of the central aisle, beyond the varnished benches, was the altar and Communion Table on a raised platform at the head of the church. The altar was decorated with ornate carvings. The Communion Table was covered by a maroon velvet cloth. A plain golden cross rested on the altar, and an open Bible beneath it. Immediately above the altar and fastened to the wall was a large arched banner with the words, Lobet den Herren in Seinem Heiligtum. Literally translated from German, this phrase proclaims, "Praise the Lord in His Holy Temple." The church seated up to 2,500 people.

A striking feature in the church was the side pulpit suspended in mid-air by five-inch thick iron rods. A suspended canopy hung over the pulpit, accessed from below through a separate outside door and a spiral staircase. Three men would ring the bells in unison when the pastor left the front step of his home and continued ringing them until he was standing in the pulpit. When the service ended, the men rang the bells until the pastor returned home.

The church had more than 40 windows illuminating the sanctuary with a flood of natural light.

The timber used to build the church was cut in the timber lands to the north, and the logs were assembled into a raft. The suppliers navigated the raft down the Volga River to the port colony of Schilling, where there was a sawmill. The bark was removed from the logs, and some were sawn into boards and timbers. The lumber was then hauled from Schilling on three interconnected wagons. Many of the long poles brought from Schilling were placed in a cradle and sawn in half. The round side of the pole was positioned to the interior of the building, and the flat side faced outward.

Men from the colony supplied the labor to build the church. Johannes Krieger, a church deacon and one of the Volga German scouts sent to America in 1874, oversaw the construction work. Few mechanical devices were used in the construction. As a result, it took over three and one-half years to complete the building.

The exterior wooden plank siding of the church was painted white. On a clear day, the church could be seen from many miles away.

The church's interior was simple in design and separated into three areas: the narthex, the nave, and the altar. The walls and ceiling were painted but largely unadorned in keeping with the beliefs of the Reformed church. Looking down the wood plank floor of the central aisle, beyond the varnished benches, was the altar and Communion Table on a raised platform at the head of the church. The altar was decorated with ornate carvings. The Communion Table was covered by a maroon velvet cloth. A plain golden cross rested on the altar, and an open Bible beneath it. Immediately above the altar and fastened to the wall was a large arched banner with the words, Lobet den Herren in Seinem Heiligtum. Literally translated from German, this phrase proclaims, "Praise the Lord in His Holy Temple." The church seated up to 2,500 people.

A striking feature in the church was the side pulpit suspended in mid-air by five-inch thick iron rods. A suspended canopy hung over the pulpit, accessed from below through a separate outside door and a spiral staircase. Three men would ring the bells in unison when the pastor left the front step of his home and continued ringing them until he was standing in the pulpit. When the service ended, the men rang the bells until the pastor returned home.

The church had more than 40 windows illuminating the sanctuary with a flood of natural light.

The second floor, supported by large columns, held the choir and the great pipe organ located over the church entry at the opposite end of the altar. Three sets of columns connected by horizontal supports carried the organ's weight. The new pipe organ was built by the well-known firm E. F. Walcker & Cie of Ludwigsburg, Germany, in 1891 (Opus 586). The beautiful organ was played by the schoolmaster and had the possibility of twenty registers or musical variations. Although it was said to be only about one-quarter the size of a full pipe organ, it would still cause the church to vibrate when the volume reached its maximum. The organ-pedaller who sat behind the organ pumped air into the different lengths of tubes, leading to a large number of pipes. It was considered one of the finest organs in the Volga German colonies.

The church had no heating system due to the difficulty retaining heat in the tall wooden structure and the danger of a fire. As a result, the winter services and ministerial acts were often held in the large Mitteldorf schoolhouse near the church, which also served as the Bethaus (Prayer House). This was problematic as the schoolhouse was too small to hold the many people who wanted to attend services at that time of year when they were not living out in the fields. Pastor Eduard Seib described his experiences serving the Volga Germans. He noted they felt very comfortable when seated close together in the school, even though the temperature would often rise to a level where the stuffy air would sometimes cause lamps and candles to flicker out during evening worship services. Apparently, this did not bother members of the congregation accustomed to the same high temperatures in their homes.

The church grounds were enclosed by a wrought iron fence, which, according to one account, was the subject of friction between Rev. Stärkel and his congregation. Money was given to the church by Americans from Akron, Ohio. Akron is Norka spelled backward. The donated money was to be used for the church building, but Rev. Stärkel wanted the fence, and he ultimately prevailed over the objections of the church members.

The church grounds were planted inside the fence with beautiful shrubbery and trees, including lilacs and acacia (locust tree). Nearby was the bell tower, which served as a communication signal throughout the colony.

Across the street from the church was the parsonage, which contained about six spacious rooms for the pastor and his family. The pastors had their own fruit orchard, vegetable garden, stable, cow shed, and outhouse. All were kept in repair by the congregation.

In 1886, a fire destroyed Pastor Stärkel's parsonage, which was later replaced by a new building.

The schoolmaster’s house (or teacherage) was near the church and the Mitteldorf schoolhouse. The congregation also maintained this house.

The last pastor in Norka was Emil Pfeiffer. Pastor Pfeiffer was arrested in 1932 and sent to Saratov. He was banned from acting as a pastor but clandestinely served the Norka congregation from time to time until his second arrest in 1934. Pastor Pfeiffer was then exiled to a location near Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan, where he was later shot to death by the Soviets.

Following Pastor Pfeiffer's banishment, the Soviet government seized church ownership. Despite the loss of the church, the Commission on Cults of the Central Executive Committee of the Volga German ASSR was informed that the faithful continued to worship in the prayer house (also the Norka Mitteldorf school). Under various pretexts, the Commission made a proposal to the Gemeinde (village administration). If the community repaid various debts within a few weeks and paid a building tax for the past five years, they could regain the use of the church. The local administration simply did not have enough money, given that the rate of taxation was up to 8% of the construction costs of the building. Lacking payment of this extortion, the church was formally closed by order of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee on October 3, 1934. The Committee recommended that the church building be used as a Soviet cultural center. Johann Georg Schleuning recalls that the building was used as the state grain warehouse until it was entirely destroyed by fire in the late 1930s.

These brutal acts by Stalin's government ended all public expressions of religion in Norka. Greater terror was yet to come. Only six years later, in 1941, all but a few ethnic Germans in Norka would be forcibly banished from their ancestral home in Russia.

The church grounds were planted inside the fence with beautiful shrubbery and trees, including lilacs and acacia (locust tree). Nearby was the bell tower, which served as a communication signal throughout the colony.

Across the street from the church was the parsonage, which contained about six spacious rooms for the pastor and his family. The pastors had their own fruit orchard, vegetable garden, stable, cow shed, and outhouse. All were kept in repair by the congregation.

In 1886, a fire destroyed Pastor Stärkel's parsonage, which was later replaced by a new building.

The schoolmaster’s house (or teacherage) was near the church and the Mitteldorf schoolhouse. The congregation also maintained this house.

The last pastor in Norka was Emil Pfeiffer. Pastor Pfeiffer was arrested in 1932 and sent to Saratov. He was banned from acting as a pastor but clandestinely served the Norka congregation from time to time until his second arrest in 1934. Pastor Pfeiffer was then exiled to a location near Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan, where he was later shot to death by the Soviets.

Following Pastor Pfeiffer's banishment, the Soviet government seized church ownership. Despite the loss of the church, the Commission on Cults of the Central Executive Committee of the Volga German ASSR was informed that the faithful continued to worship in the prayer house (also the Norka Mitteldorf school). Under various pretexts, the Commission made a proposal to the Gemeinde (village administration). If the community repaid various debts within a few weeks and paid a building tax for the past five years, they could regain the use of the church. The local administration simply did not have enough money, given that the rate of taxation was up to 8% of the construction costs of the building. Lacking payment of this extortion, the church was formally closed by order of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee on October 3, 1934. The Committee recommended that the church building be used as a Soviet cultural center. Johann Georg Schleuning recalls that the building was used as the state grain warehouse until it was entirely destroyed by fire in the late 1930s.

These brutal acts by Stalin's government ended all public expressions of religion in Norka. Greater terror was yet to come. Only six years later, in 1941, all but a few ethnic Germans in Norka would be forcibly banished from their ancestral home in Russia.

Sources

Bauer, Reuben Alexander. One of Many. Edmonton, Alta.: 1965. 31-43. Print.

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Dalton, Hermann. Geschichte Der Reformirten Kirche in Russland: Kirchenhistorische Studie. Trans. William Pickelhaupt. Gotha: R. Besser, 1865. Print.

Litzenberger, Olga. Deutsche Evangelische Siedlungen an Der Wolga. Trans. Johannes Herzog and Paul Höringklee. Nürnberg: HFDR, 2013. 441-452. Print.

Olson, Marie Miller., and Anna Miller. Reisbick. Norka, a German Village in Russia. Lincoln, Nebraska: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1986. 25. Print.

Pickelhaupt, Bill., trans. Die Evangelische-Lutherischen Gemeinden in Russland. Vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Zentral-Komitee Der Unterstützungs-Kasse für evangelische-lutherische Gemeinden in Russland, 1909. Print.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums."Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): 152. Print.

Schnurr, Joseph. Die Kirchen Und Das Religiöse Leben Der Rußlanddeutschen. Stuttgart: AER-Verlag, 1978. 322. Print.

Terjochin, Sergej. Deutsche Architektur an Der Wolga. Berlin: Westkreuz Verlag, 1993. 49. Print.

Walcker-Mayer, Gerhard. "Walcker-Organs Recounting History." 0586 Norka. Walcker-Orgelbau Seit 1780, n.d. Web. June 2013. <http://www.walcker.com/opus/0001_0999/586-norka.html>.

Were, Amelia. "A History of the Krieger Family from Norka, Russia."

"Protestantism in Russia." Christian Reflector & Christian Watchman [Boston] 17 Aug. 1848: Print.

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Interview by George Brill. Print.

Dalton, Hermann. Geschichte Der Reformirten Kirche in Russland: Kirchenhistorische Studie. Trans. William Pickelhaupt. Gotha: R. Besser, 1865. Print.

Litzenberger, Olga. Deutsche Evangelische Siedlungen an Der Wolga. Trans. Johannes Herzog and Paul Höringklee. Nürnberg: HFDR, 2013. 441-452. Print.

Olson, Marie Miller., and Anna Miller. Reisbick. Norka, a German Village in Russia. Lincoln, Nebraska: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1986. 25. Print.

Pickelhaupt, Bill., trans. Die Evangelische-Lutherischen Gemeinden in Russland. Vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Zentral-Komitee Der Unterstützungs-Kasse für evangelische-lutherische Gemeinden in Russland, 1909. Print.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums."Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): 152. Print.

Schnurr, Joseph. Die Kirchen Und Das Religiöse Leben Der Rußlanddeutschen. Stuttgart: AER-Verlag, 1978. 322. Print.

Terjochin, Sergej. Deutsche Architektur an Der Wolga. Berlin: Westkreuz Verlag, 1993. 49. Print.

Walcker-Mayer, Gerhard. "Walcker-Organs Recounting History." 0586 Norka. Walcker-Orgelbau Seit 1780, n.d. Web. June 2013. <http://www.walcker.com/opus/0001_0999/586-norka.html>.

Were, Amelia. "A History of the Krieger Family from Norka, Russia."

"Protestantism in Russia." Christian Reflector & Christian Watchman [Boston] 17 Aug. 1848: Print.

Last updated June 27, 2024