History > Recruitment of the Colonists - 1766

Recruitment of the Colonists - 1766

After the Seven Years' War ended in 1763, the population in central Europe began to recover, and farmland was again in short supply. Poor harvests in the early 1760s drove up food prices, and shortages became prevalent. Many families without land lived on the edge of existence and had little prospect of a stable life. It was a difficult time, especially for the landless lower classes. Many people wanted a better life, even if that meant leaving their homeland.

The timing and appeal of Catherine II's Manifesto in 1763 could not have come at a better time. The Russian government's promises of free land, freedom of religion, the right of self-government, exemption from taxation for 30 years, and exemption from military service in perpetuity must have seemed like a godsend. While there were risks to be considered, migration to Russia offered many the hope for a better life.

The timing and appeal of Catherine II's Manifesto in 1763 could not have come at a better time. The Russian government's promises of free land, freedom of religion, the right of self-government, exemption from taxation for 30 years, and exemption from military service in perpetuity must have seemed like a godsend. While there were risks to be considered, migration to Russia offered many the hope for a better life.

Russian representatives published the Manifesto in newspapers and distributed printed copies throughout the German-speaking areas of Europe, luring thousands with its promises of a better life in a faraway land. The recruiters were divided into two categories: those directly representing the Russian government and a group of private recruiters authorized by the Russian government to establish their own colonies along the lower Volga River. About 56 percent of the colonists who arrived in the Saratov area were part of transport groups led by private recruiters. Norka was among the crown colonies directly organized by the Russian government.

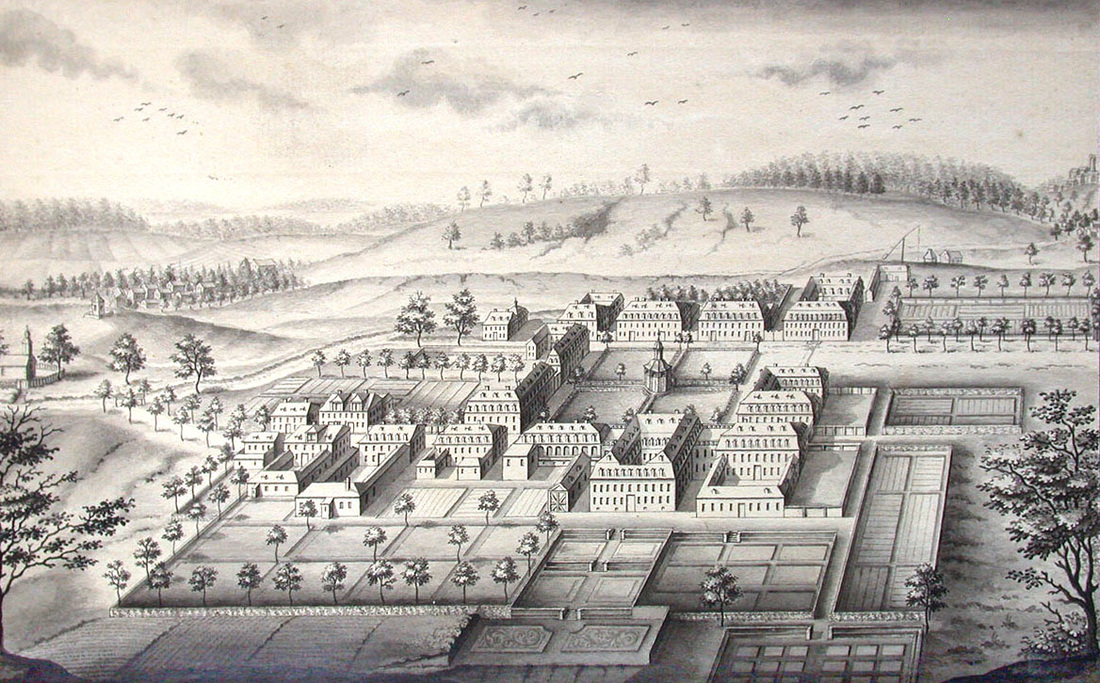

Given that most of the people who settled in the colony of Norka originated from places located in the Duchy of Hessen and, more specifically, the County of Isenburg, it is very likely that these colonists registered and prepared for the journey to Russia at the recruiting headquarters established in Büdingen. Büdingen is a picturesque city located south of the Wetterau district below the Vogelsberg Mountains. The town is 15 kilometers northwest of Gelnhausen and about 40 kilometers northeast of Frankfurt am Main. In 1766, the population was between 1,500 and 2,000 people.

Given that most of the people who settled in the colony of Norka originated from places located in the Duchy of Hessen and, more specifically, the County of Isenburg, it is very likely that these colonists registered and prepared for the journey to Russia at the recruiting headquarters established in Büdingen. Büdingen is a picturesque city located south of the Wetterau district below the Vogelsberg Mountains. The town is 15 kilometers northwest of Gelnhausen and about 40 kilometers northeast of Frankfurt am Main. In 1766, the population was between 1,500 and 2,000 people.

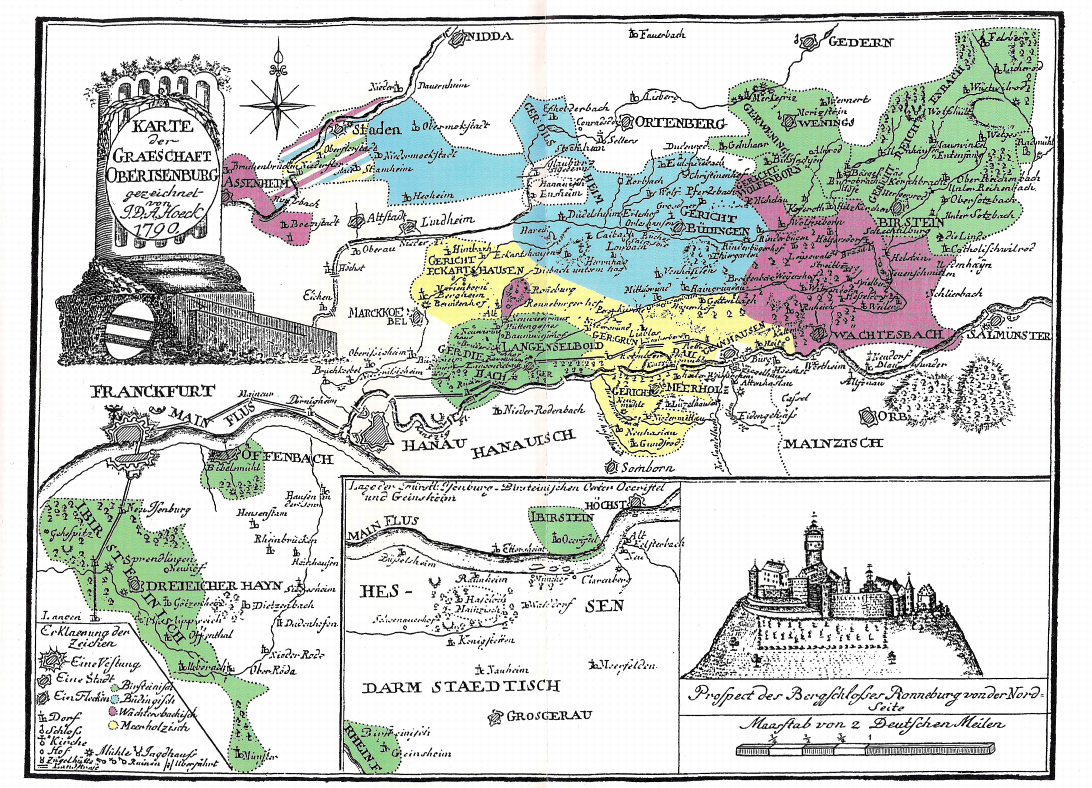

In 1766, the County of Isenburg was divided into four partitions named after the residences at Birstein, Büdingen, Wächtersbach, and Meerholz. Each partition had a castle with its own administration. The Counts of Birstein were Catholic, and the other Counts were Protestant. Isenburg-Büdingen became a Protestant county in 1521 when Martin Luther reportedly passed through. Later, Isenburg-Büdingen followed the Calvinist or Reformed faith. The Isenburg-Birstein family was distantly related to Catherine II (Catherine the Great), a former German princess and, at the time, Empress of Russia. Catherine regularly sent the family her New Year's greetings.

Map of upper Isenburg in 1790. Source: "1790 Hoeck Karte Oberisenburg" von J. D. A. Hoeck (1763–1839), alternative Schreibweise: Johann D. Hoeck, Johann Daniel Albrecht Höck, Johann D. Höck, D. J. D. A. Höck, J. D. A. Höck, Johann D. Hök - Historisch-statistische Topographie der Grafschaft Oberisenburg, Jäger, Frankfurt am Main: 1790. Lizenziert unter Gemeinfrei über Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1790_Hoeck_Karte_Oberisenburg.png#/media/File:1790_Hoeck_Karte_Oberisenburg.png

People from all parts of Isenburg emigrated from Germany to Russia. However, recruitment of colonists by Russian officials was only allowed in Büdingen by order of Count Gustav Friedrich.

Count Gustav Friedrich maintained a close relationship with the Russian government and was sympathetic towards his subjects who wanted to emigrate. Those who desired to live in Russia were required to obtain permission, which could be granted if it was determined that all of their taxes and debts had been paid.

Count Gustav Friedrich maintained a close relationship with the Russian government and was sympathetic towards his subjects who wanted to emigrate. Those who desired to live in Russia were required to obtain permission, which could be granted if it was determined that all of their taxes and debts had been paid.

In the recent past, the Counts of Isenburg themselves had recruited settlers. After suffering significant population losses in the Thirty Years' War, the Counts of Isenburg had fallen on hard times, and an attempt was made to attract new inhabitants and industry. The Counts offered economic advantages, generous privileges, and the guarantee of unprecedented religious freedom and tolerance. This was a rare exception in a time of strict confessional barriers.

In Büdingen, Count Ernst Casimir, the father of Count Gustav Frederic, proclaimed in his so-called "Edict of Tolerance" that "the authority of the ruler shall not be extended to the conscience of his subjects."

In Büdingen, Count Ernst Casimir, the father of Count Gustav Frederic, proclaimed in his so-called "Edict of Tolerance" that "the authority of the ruler shall not be extended to the conscience of his subjects."

The County of Isenburg-Büdingen, home to many who settled in Norka, officially followed the Calvinist or Reformed faith. Unsurprisingly, approximately 90 percent of the households that settled in Norka professed to be followers of the Reformed faith.

Isenburg-Büdingen also became home to a very diverse collection of people and religions. Persecuted French Huguenots, who were Calvinists, settled in Offenbach and near the Jerusalem gate in Büdingen. Dunkers living in Düdelsheim (near Büdingen) went to Pennsylvania in 1714 under the leadership of Peter Becker, who became the founder of the American Church of the Brethren. Another well-known group was the Herrnhuter, or Moravians, who first leased the ruined Ronneburg Castle (also near Büdingen) from the Counts of Isenburg in 1736. In 1738, they founded a large settlement in 1738 at the Herrnhaag, not far from Ronneburg Castle. From there, their leader, Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, undertook his great journeys to the West Indies and the North American continent. Another persecuted religious community, the "Community of True Inspiration," was based for a time in Ronneburg Castle. The Community collectively emigrated from Ronneburg to America in 1842, purchasing 5,000 acres near Buffalo, New York. In 1855, this group founded the Amana Colonies in eastern Iowa. The Amana Church Society still exists today, practices old traditions, and considers Ronneburg as one of its spiritual centers.

Isenburg-Büdingen also became home to a very diverse collection of people and religions. Persecuted French Huguenots, who were Calvinists, settled in Offenbach and near the Jerusalem gate in Büdingen. Dunkers living in Düdelsheim (near Büdingen) went to Pennsylvania in 1714 under the leadership of Peter Becker, who became the founder of the American Church of the Brethren. Another well-known group was the Herrnhuter, or Moravians, who first leased the ruined Ronneburg Castle (also near Büdingen) from the Counts of Isenburg in 1736. In 1738, they founded a large settlement in 1738 at the Herrnhaag, not far from Ronneburg Castle. From there, their leader, Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, undertook his great journeys to the West Indies and the North American continent. Another persecuted religious community, the "Community of True Inspiration," was based for a time in Ronneburg Castle. The Community collectively emigrated from Ronneburg to America in 1842, purchasing 5,000 acres near Buffalo, New York. In 1855, this group founded the Amana Colonies in eastern Iowa. The Amana Church Society still exists today, practices old traditions, and considers Ronneburg as one of its spiritual centers.

Catherine appointed Johann Matthias Simolin, the Russian Ambassador to the Reichstag (the Diet of the Realm at this time), to act as special commissioner to head the Russian crown's recruitment effort. Simolin's deputies were Friederich Meixner, whose headquarters were at Ulm, and Johann Facius from Hanau, initially headquartered at Frankfurt am Main in October 1765.

The recruitment of colonists often brought strong reactions from the German authorities, who often did not want their subjects to emigrate. Many German rulers enacted laws threatening severe punishment, confiscating goods, and prohibiting property sales for anyone considering emigration. Despite his diplomatic protection, the authorities in Frankfurt forced Facius out of the city, and he soon established a new headquarters in Büdingen in late February of 1766.

Facius and his representatives of the Russian crown were much more scrupulous in their recruiting activities than the private recruiters, ensuring that the colonists would have the desired skills and requiring them to present documentation of their release by the local authorities. The Russian government had to be careful not to upset diplomatic relationships in the German territories allowing emigration.

In some instances, the Counts of Isenburg assisted those who wanted to become Russian colonists, knowing they provided little tax revenue. For example, on May 15, 1766, Wilhelm Häfner from Büdingen, who was 17 Gulden in debt from unpaid taxes, was encouraged to immigrate to Russia. Likewise, Philipp Jakob Pauli, who later settled in Norka, asked the authorities to waive his tax debt so he could have “a penny for his journey." The record of his petition shows the following comment: “The person who has nothing can give nothing.” Pauli was allowed to emigrate without paying his debt. In some cases, debts were paid by the Russian representatives.

As thousands of colonists surged into Büdingen during the spring of 1766, Count Gustav Friedrich strove to keep everything calm and incident-free to avoid trouble with neighboring territories. His administrative advisor and confidant, Moritz Albert Reich, supervised the activities. He also retained the right to deny emigration in cases where personal documents were not presented in the prescribed manner. But despite that, these restrictions were not taken too seriously as reports from the nearby city of Fulda mentioned that people secretly went to Büdingen to get to "Astrakhan." Evidence in the Isenburg archives shows that some people tried to avoid making the required emigration petition to the authorities. These people secretly attempted to escape without paying their debts and required fees. Some were caught and punished.

The Russian government preferred young married couples with families but also allowed some single men to register as colonists. Financial incentives that benefited married couples encouraged many singles to marry before departure for Russia. Between February 24 and July 8, 1766, 375 marriages occurred in Büdingen’s Marienkirche (St. Mary’s Church). Additional marriages took place in Lübeck and other locations before the sea voyage began. The marriage records in both locations list several couples settling in Norka over a year later. The church records also indicate that among the colonists, two men, five women, and 15 children died during their time in Büdingen. Several colonist children were born in Büdingen, and Facius is listed as godfather to some of them.

Most emigrants were young people whose occupations and professions included farmers, bakers, weavers, carpenters, blacksmiths, potters, tanners, merchants, and teachers. Most families consisted of four to six people.

At the gathering point in Büdingen, the recruits signed documents committing themselves as colonists under the provisions of the Manifesto. At the expense of the Russian government, they were housed and provided with financial support, which amounted to 16 Kreuzer for men, 10 Kreuzer for a woman and adolescents, and 6 Kreuzer for each child. During the spring and early summer of 1766, Büdingen must have been very crowded due to the influx of prospective colonists. According to town records, the fact that the local population benefited from the money spent by the recruits helped keep the situation calm and incident-free. In May 1766, the bakers in Büdingen asked Count Gustav Friedrich to lift the milling restrictions so they could buy from mills outside the city to make enough bread for the emigrants.

The recruitment activities in Büdingen continued until July 1766. At this time, the colonists were organized into transport groups of 60 to 100 people. Each group was assigned a Vorsteher (or group leader) from among the colonists. Together, they traveled by land and water to the North German port of Lübeck, where the next part of their journey would begin. The colonists needed to start their voyage to Russia by the end of September before winter weather made travel impossible.

Many of the recruits who founded the colony of Norka were among the last groups of colonists to leave their German homeland.

By mid-1766, there was significant pressure to halt Russian migration. In a letter dated May 17, 1766, Prince A.V. Golitsyn insisted that Catharine II stop the recruitment of colonists to protect relationships with the various German states. Two days earlier, Simolin had already discontinued the recruitment of colonists without approval from St. Petersburg.

In the more tolerant lands of Isenburg, Johann Facius continued his work until October 1766. After that time, there is no trace of further recruitment activity in Büdingen. In November 1766, a declaration announcing the cessation of the Manifesto was published in newspapers. The door to Russia had closed.

As thousands of colonists surged into Büdingen during the spring of 1766, Count Gustav Friedrich strove to keep everything calm and incident-free to avoid trouble with neighboring territories. His administrative advisor and confidant, Moritz Albert Reich, supervised the activities. He also retained the right to deny emigration in cases where personal documents were not presented in the prescribed manner. But despite that, these restrictions were not taken too seriously as reports from the nearby city of Fulda mentioned that people secretly went to Büdingen to get to "Astrakhan." Evidence in the Isenburg archives shows that some people tried to avoid making the required emigration petition to the authorities. These people secretly attempted to escape without paying their debts and required fees. Some were caught and punished.

The Russian government preferred young married couples with families but also allowed some single men to register as colonists. Financial incentives that benefited married couples encouraged many singles to marry before departure for Russia. Between February 24 and July 8, 1766, 375 marriages occurred in Büdingen’s Marienkirche (St. Mary’s Church). Additional marriages took place in Lübeck and other locations before the sea voyage began. The marriage records in both locations list several couples settling in Norka over a year later. The church records also indicate that among the colonists, two men, five women, and 15 children died during their time in Büdingen. Several colonist children were born in Büdingen, and Facius is listed as godfather to some of them.

Most emigrants were young people whose occupations and professions included farmers, bakers, weavers, carpenters, blacksmiths, potters, tanners, merchants, and teachers. Most families consisted of four to six people.

At the gathering point in Büdingen, the recruits signed documents committing themselves as colonists under the provisions of the Manifesto. At the expense of the Russian government, they were housed and provided with financial support, which amounted to 16 Kreuzer for men, 10 Kreuzer for a woman and adolescents, and 6 Kreuzer for each child. During the spring and early summer of 1766, Büdingen must have been very crowded due to the influx of prospective colonists. According to town records, the fact that the local population benefited from the money spent by the recruits helped keep the situation calm and incident-free. In May 1766, the bakers in Büdingen asked Count Gustav Friedrich to lift the milling restrictions so they could buy from mills outside the city to make enough bread for the emigrants.

The recruitment activities in Büdingen continued until July 1766. At this time, the colonists were organized into transport groups of 60 to 100 people. Each group was assigned a Vorsteher (or group leader) from among the colonists. Together, they traveled by land and water to the North German port of Lübeck, where the next part of their journey would begin. The colonists needed to start their voyage to Russia by the end of September before winter weather made travel impossible.

Many of the recruits who founded the colony of Norka were among the last groups of colonists to leave their German homeland.

By mid-1766, there was significant pressure to halt Russian migration. In a letter dated May 17, 1766, Prince A.V. Golitsyn insisted that Catharine II stop the recruitment of colonists to protect relationships with the various German states. Two days earlier, Simolin had already discontinued the recruitment of colonists without approval from St. Petersburg.

In the more tolerant lands of Isenburg, Johann Facius continued his work until October 1766. After that time, there is no trace of further recruitment activity in Büdingen. In November 1766, a declaration announcing the cessation of the Manifesto was published in newspapers. The door to Russia had closed.

A film tour of Büdingen in the heart of Hessen. Many families that settled in Norka lived in Büdingen and the surrounding villages. Nearly all of the families settling in Norka gathered here before starting their journey to Russia in 1766.

Sources

Bonwetsch, Gerhard. Geschichte Der Deutschen Kolonien an Der Wolga. Stuttgart: J. Engelhorns Nachf., 1919. 26. Print.

Decker, Klaus-Peter. Büdingen Als Sammelplatz Der Auswanderung an Die Wolga 1766. Büdingen: Geschichtswerkstatt Büdingen, 2009. Print.

Decker, Klaus-Peter. "Büdingen in the County of Ysenburg as a Recruitment and Gathering Place of the Russian Emigration." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 24.2 (2001): 9-15.

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Printed by Augstums Printing Service, 2005. Print.

Hutton, J. E. A History of the Moravian Church. London: Moravian Publication Office, 1909. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan, and Dona B. Reeves-Marquardt. German Migration to the Russian Volga (1764-1767): Origins and Destinations. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2003. Print.

"Places of Interest - Town History." Touristik Büdingen. N.p., n.d. Web. May 2016. <http://www.buedingen.info/en/places-of-interest/town-history.html>.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Pleve, I. R. Lists of Colonists to Russia in 1766: Reports by Ivan Kulberg. Saratov, Russia: Saratov State Technical U, 2010. Print.

Williams, Hattie Plum. The Czar's Germans: With Particular Reference to the Volga Germans. Ed. Emma S. Haynes, Phillip B. Legler, and Gerda Stroh. Walker. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1975. Print.

Decker, Klaus-Peter. Büdingen Als Sammelplatz Der Auswanderung an Die Wolga 1766. Büdingen: Geschichtswerkstatt Büdingen, 2009. Print.

Decker, Klaus-Peter. "Büdingen in the County of Ysenburg as a Recruitment and Gathering Place of the Russian Emigration." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 24.2 (2001): 9-15.

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Printed by Augstums Printing Service, 2005. Print.

Hutton, J. E. A History of the Moravian Church. London: Moravian Publication Office, 1909. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan, and Dona B. Reeves-Marquardt. German Migration to the Russian Volga (1764-1767): Origins and Destinations. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2003. Print.

"Places of Interest - Town History." Touristik Büdingen. N.p., n.d. Web. May 2016. <http://www.buedingen.info/en/places-of-interest/town-history.html>.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Pleve, I. R. Lists of Colonists to Russia in 1766: Reports by Ivan Kulberg. Saratov, Russia: Saratov State Technical U, 2010. Print.

Williams, Hattie Plum. The Czar's Germans: With Particular Reference to the Volga Germans. Ed. Emma S. Haynes, Phillip B. Legler, and Gerda Stroh. Walker. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1975. Print.

Last updated November 19, 2023