History > Voyage to Russia

Voyage to Russia - 1766

A voyage is defined as "a course of travel or passage, especially a long journey by water to a distant place," and this was certainly true for the colonists bound for Russia.

Russian recruiters promoted Catherine's Manifesto throughout the Germanic regions of Europe, luring thousands with its promises of a better life in a faraway land.

Russian recruiters promoted Catherine's Manifesto throughout the Germanic regions of Europe, luring thousands with its promises of a better life in a faraway land.

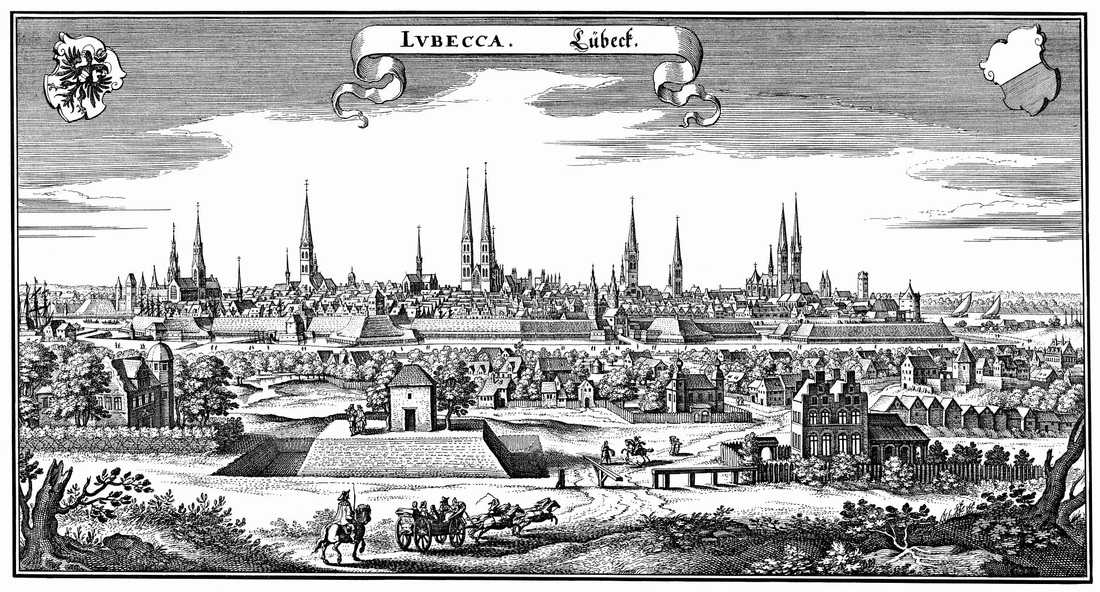

Given that most Norka colonists originated in Isenburg or Hessen, they most likely gathered in the town of Büdingen before traveling by land and water to the Baltic Sea port of Lübeck. The colonists departed from Büdingen and traveled by wagon northeast to Weimar and Halle. From the navigable waters on the Saale and Elbe Rivers near Magdeburg, they proceeded downriver to Lauenburg by boat. From Lauenberg, they probably traveled overland on the Old Salt Route (Alte Salzstrasse) to the port city of Lübeck.

Lübeck was favorably located and had long been a part of the Hanseatic League, a medieval mercantile association that prospered from maritime trade in northern Europe. Lübeck enjoyed long and flourishing trade relations with Russia and was on excellent terms with Catherine II's government.

Russian officials appointed Commissioner Christoph Heinrich Schmidt (a Lübeck merchant) to organize the transfer of the colonists from Lübeck to Russia. The Commissioner was paid 500 to 600 rubles annually and was responsible for providing housing in Lübeck, avoiding conflicts with the local population, and arranging ships to transport the colonists to Russia.

In Lübeck, the colonists were housed in various accommodations, including specially built barracks, hotels, and warehouses modified as temporary living spaces. The colonists were given a daily allowance of 16 Kreuzers (in English - Kreutzer) for men, 10 Kreuzers for women and adolescents, and 6 Kreuzers for babies.

In Lübeck, the colonists were housed in various accommodations, including specially built barracks, hotels, and warehouses modified as temporary living spaces. The colonists were given a daily allowance of 16 Kreuzers (in English - Kreutzer) for men, 10 Kreuzers for women and adolescents, and 6 Kreuzers for babies.

In the spring of 1766, more than 10,000 colonists lived in and around the city. Severe weather at the end of April and early May prevented travel on the Baltic Sea, resulting in a backlog of departures. Most settling in Norka arrived in Lübeck in the last months of emigration to Russia. At this time, Commissioner Schmidt was suffering from tuberculosis, which halted his work. Fearful authorities in Lübeck did all they could to prevent the mass of emigrants from entering the city.

Gabriel Christian Lemke (a Lübeck lawyer) was appointed by the Russian government to replace Schmidt, who did not retire but did not have the strength to continue his work. Schmidt died on May 30, 1766. Lemke hired additional staff and obtained loans to cover higher-than-anticipated costs related to the delays. Lemke also reorganized the work and selected leaders of each group, the Vorsteher, who distributed provisions amongst their group and helped maintain order.

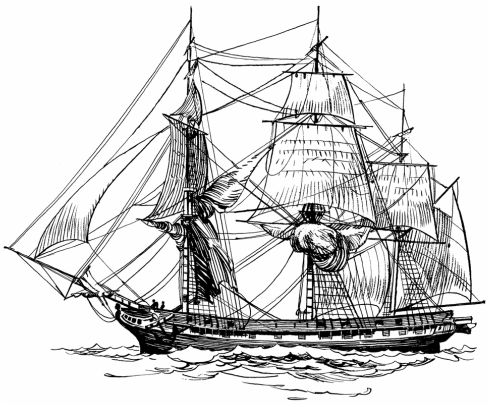

Before his death, Commissioner Schmidt initially contracted for transport ships from Lübeck merchants. When it became apparent that the flow of colonists was greater than the Lübeck ship capacity initially under contract, two large English ships capable of carrying up to 1,100 people were chartered. Several Russian packet boats and pinks also provided significant assistance in transporting the colonists. Packet boats generally accommodated 70 to 80 people, and the pinks typically carried 280 to 290 people per voyage. The Commissioners were allocated 2 rubles per male and 1.5 rubles per female and child to cover the cost of sea transport. These sailing vessels were usually used for cargo and were poorly adapted for transporting passengers. At least 26 ships transported colonists that would settle in Norka in 1767.

Gabriel Christian Lemke (a Lübeck lawyer) was appointed by the Russian government to replace Schmidt, who did not retire but did not have the strength to continue his work. Schmidt died on May 30, 1766. Lemke hired additional staff and obtained loans to cover higher-than-anticipated costs related to the delays. Lemke also reorganized the work and selected leaders of each group, the Vorsteher, who distributed provisions amongst their group and helped maintain order.

Before his death, Commissioner Schmidt initially contracted for transport ships from Lübeck merchants. When it became apparent that the flow of colonists was greater than the Lübeck ship capacity initially under contract, two large English ships capable of carrying up to 1,100 people were chartered. Several Russian packet boats and pinks also provided significant assistance in transporting the colonists. Packet boats generally accommodated 70 to 80 people, and the pinks typically carried 280 to 290 people per voyage. The Commissioners were allocated 2 rubles per male and 1.5 rubles per female and child to cover the cost of sea transport. These sailing vessels were usually used for cargo and were poorly adapted for transporting passengers. At least 26 ships transported colonists that would settle in Norka in 1767.

Historian Igor Pleve states that lists of the colonists were made in Lübeck as they boarded the ships. These records were necessary for the compensation of the Russian-appointed Commissioners. Unfortunately, these long-sought-after departure records have not been found.

The approximately 900-mile sailing from Lübeck, across the Baltic Sea to Kronstadt, Russia, would typically average nine days. Inclement weather and unfavorable winds could prolong the journey to several weeks. The colonists departed from Lübeck, full of hope and anxiety for the future. As they saw the church spires that shaped the city's skyline and the old lighthouse at Travemünde fade in the distance, they surely felt great sadness, knowing they would never see their homes again.

The approximately 900-mile sailing from Lübeck, across the Baltic Sea to Kronstadt, Russia, would typically average nine days. Inclement weather and unfavorable winds could prolong the journey to several weeks. The colonists departed from Lübeck, full of hope and anxiety for the future. As they saw the church spires that shaped the city's skyline and the old lighthouse at Travemünde fade in the distance, they surely felt great sadness, knowing they would never see their homes again.

From April to October 1766, nearly 24,000 colonists arrived in Russia from Lübeck. This amounted to over 74 percent of the colonists arriving in Russia between 1763 and 1772. Most of the colonists that settled in Norka arrived in Russia during July and August.

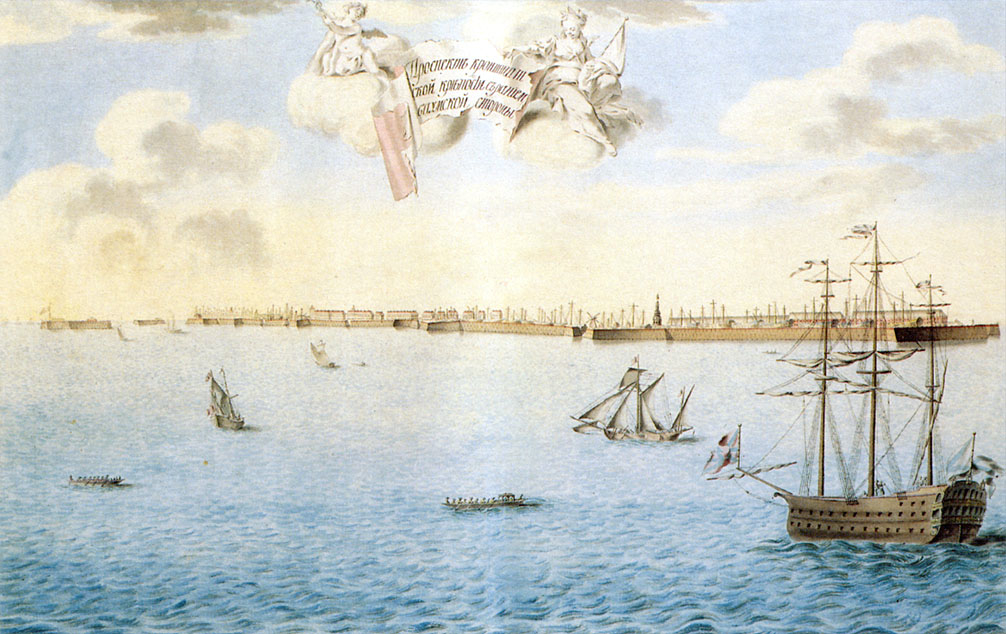

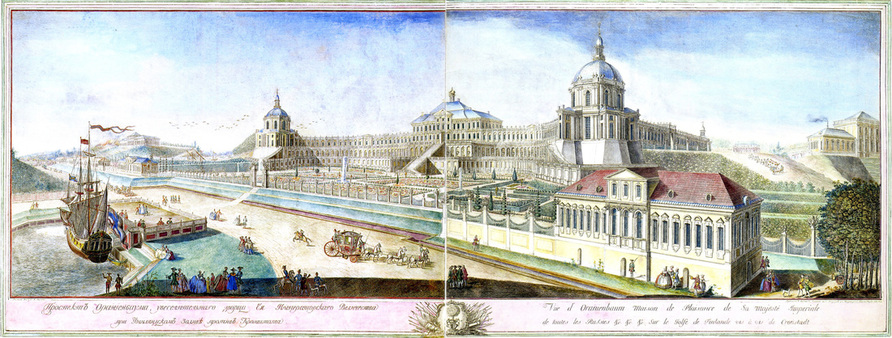

Colonists arriving in Russia by sea first disembarked at Kronstadt, where their documents were verified, and customs inspections were made. Kronstadt is an island fortress designed to protect the sea lanes of St. Petersburg. From Kronstadt, the colonists were immediately transported a short distance by six-oared boats manned by Russian sailors to the town of Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov) on the mainland.

Colonists arriving in Russia by sea first disembarked at Kronstadt, where their documents were verified, and customs inspections were made. Kronstadt is an island fortress designed to protect the sea lanes of St. Petersburg. From Kronstadt, the colonists were immediately transported a short distance by six-oared boats manned by Russian sailors to the town of Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov) on the mainland.

After arrival in Oranienbaum, the colonists were under the supervision of military Commissar and Titular Councillor Ivan Kulberg (Johann Kuhlberg), a Russian officer of German origin. Kulberg and his assistants made lists of the colonists for the Chancery of Oversight of Foreigners in Saratov. The lists were made for each ship's arrival and included the date of arrival in Russia, the port of departure, the owner of the ship, the name of the ship, and the name of the captain. The colonists were each listed by name and usually grouped in families. Generally, their place of origin in Western Europe and their religion, children's age, and occupation were provided. The information was recorded in Cyrillic script, and the accuracy depended on the work of each Russian clerk, who may have had a limited understanding of the German language and various dialects.

Map of Lomonosov (formerly Oranienbaum) showing the Grand Palace of Catherine II (section A-1). The canal which led from the Gulf of Finland to the palace can be clearly seen although it no longer is open to the sea. The Volga German colonists arrived on the mainland through this canal after their initial landing at the island fortress of Kronstadt. Courtesy of Steve Schreiber (2006).

Large groups of colonists that would settle in Norka sailed from Lübeck. They arrived at Kronstadt on July 19, 1766, aboard the Russian pink Slon (the Russian word for Elephant) commanded by Lieutenant Sergey Panov. Over 40 households, primarily from Isenburg, traveled together on this ship. Kulberg recorded three Vorsteher (leaders) traveling in this group: Johann Conrad Weigandt, Johann Heinrich Brill, and Philipp Peter Roth. At its founding, Norka was initially named Weigandt to honor its primary leader, Johann Conrad Weigandt. Other colonists who settled in Norka arrived at Kronstadt on at least 25 different ships from early May to the end of August 1766. Among the other ships, those carrying the majority of colonists who would settle in Norka include the Apollo, Fortitudo, Novaya Dvinka, and Strelna.

The colonists stayed in Oranienbaum for an average of one or two months, learning about Russian laws and traditions and preparing for the journey ahead. Each colonist also swore an oath of loyalty to the Russian crown. The oath was often administered at the Lutheran church in Oranienbaum by the Rev. Johann Christoph König. It was said that Catherine II would occasionally greet the colonists in their native tongue from the balcony of her Grand Palace in Oranienbaum, which overlooked the canal providing access to the Gulf of Finland.

The colonists stayed in Oranienbaum for an average of one or two months, learning about Russian laws and traditions and preparing for the journey ahead. Each colonist also swore an oath of loyalty to the Russian crown. The oath was often administered at the Lutheran church in Oranienbaum by the Rev. Johann Christoph König. It was said that Catherine II would occasionally greet the colonists in their native tongue from the balcony of her Grand Palace in Oranienbaum, which overlooked the canal providing access to the Gulf of Finland.

The colonists temporarily lived in wooden barracks constructed for soldiers from Holstein who served Russian Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich. Peter was born in the German city of Kiel and was also the Duke of Holstein. In Oranienbaum, Peter created his own personal Guard, consisting of soldiers imported from his native Holstein, and these soldiers were educated and clothed in uniforms along Prussian lines. Peter entered an arranged marriage with Sophie Friederike Auguste from the small German principality of Anhalt-Zerbst, and she became Grand Duchess Catherine Alexeyevna. Following the death of his aunt, Empress Elizabeth, Peter became Emperor Peter III of Russia in 1761. After Peter's assassination, Catherine became Empress of Russia and would later be known as Catherine the Great. Ironically, the barracks built by Peter for his Holstein soldiers would be used to facilitate Catherine's colonization program.

The Russian government provided medical care for the colonists, administered by Dr. Prais at a hospital near the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St. Petersburg. At the Chancery in St. Petersburg, the new arrivals received an allowance of 12 to 18 rubles per family or 4 rubles for single and unmarried people. Before departing on the next part of the journey to the Volga, the colonists were also provided with winter clothing and necessary household items.

The Russian government provided medical care for the colonists, administered by Dr. Prais at a hospital near the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St. Petersburg. At the Chancery in St. Petersburg, the new arrivals received an allowance of 12 to 18 rubles per family or 4 rubles for single and unmarried people. Before departing on the next part of the journey to the Volga, the colonists were also provided with winter clothing and necessary household items.

On its face, Catherine's Manifesto allowed the colonists to settle anywhere in Russia they desired. In practice, the colonists were strongly directed by Kulberg and his assistants to settle in the colonies near Saratov. Kulberg had to persuade many colonists, especially the many craftsmen and artisans, to continue on to the lower Volga, where they could practice their trade in addition to farming. This deviation from Catherine's Manifesto was likely a practical matter for the Russian government. The government had established an efficient system for moving and settling large numbers of people near Saratov. The cost and resources needed to move colonists anywhere they desired in Russia would have been prohibitive.

Sources

Idt, Andreas and Rauschenbach, Georg. Auswanderung deutsche Kolonisten nach Russland im Jahre 1766 (Second edition). Moscow: 2019.

Pleve, I. R. Lists of Colonists to Russia in 1766: Reports by Ivan Kulberg. Saratov, Russia: Saratov State Technical U, 2010. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Pleve, I.R. Email to Steven Schreiber dated 28 March 2020. Dr. Pleve states after the ships of the colonists landed in Kronstadt their documents were examined and customs checks were made. With those steps completed the colonists were immediately sent by boats to Oranienbaum were lists were compiled by Ivan Kulberg. And after that, the colonists were sent to St. Petersburg, to the Chancery to receive their per diem, winter clothing, other necessities and medical assistance if needed. The colonists remained in Oranienbaum for several months before being sent to the Volga in transport groups.

Navigable Waterways in the German Reich, 1903 w903d_e_a4_mb.pdf

Pleve, I. R. Lists of Colonists to Russia in 1766: Reports by Ivan Kulberg. Saratov, Russia: Saratov State Technical U, 2010. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Pleve, I.R. Email to Steven Schreiber dated 28 March 2020. Dr. Pleve states after the ships of the colonists landed in Kronstadt their documents were examined and customs checks were made. With those steps completed the colonists were immediately sent by boats to Oranienbaum were lists were compiled by Ivan Kulberg. And after that, the colonists were sent to St. Petersburg, to the Chancery to receive their per diem, winter clothing, other necessities and medical assistance if needed. The colonists remained in Oranienbaum for several months before being sent to the Volga in transport groups.

Navigable Waterways in the German Reich, 1903 w903d_e_a4_mb.pdf

Last updated December 7, 2023