Traditions > Holidays > New Year Traditions

New Year Traditions

The days from late December until early January were filled with traditions, many of which had been transplanted from the colonist's places of origin in Germanic Europe and influenced by their new homeland in Russia over time.

At the approach of the Neujahrsfeier (New Year's celebration), it was time to not only remember all that had happened in the year just past but also to look forward with hope to the year ahead.

The 12 days from December 25th to January 6th predicted the weather for the coming 12 months. For example, the weather on December 27th (the third day in the sequence) represented what would be expected in March next year (the third month of the year). Others predicted the weather by observing onion skins sprinkled with salt.

Many marriages took place during the week between Christmas and New Year's Day. The traditional wedding date was the second day of Christmas (December 26th), when multiple couples would gather to take their marriage vows.

At the approach of the Neujahrsfeier (New Year's celebration), it was time to not only remember all that had happened in the year just past but also to look forward with hope to the year ahead.

The 12 days from December 25th to January 6th predicted the weather for the coming 12 months. For example, the weather on December 27th (the third day in the sequence) represented what would be expected in March next year (the third month of the year). Others predicted the weather by observing onion skins sprinkled with salt.

Many marriages took place during the week between Christmas and New Year's Day. The traditional wedding date was the second day of Christmas (December 26th), when multiple couples would gather to take their marriage vows.

The New Year's celebration began with the Neujahrsmesse (New Year's Eve church service). The service was held in the schoolhouse because the church in Norka was closed during the winter due to the difficulty of heating the large wooden church and the ever-present danger of a fire.

As the worship service ended, the bells in the tower rang loudly, signaling a farewell to the old year.

In Norka, the Christkind (a young woman representing the Christ Child) appeared as she did on Weihnachten (Christmas). The Neujahrsmann (the New Year's Man) also visited the village on this holiday. The Neujahrsmann tradition was brought from the colonists' homelands in the 1760s. This character went from house to house and wished the residents good luck and blessings in the coming year. In return, he received a small token of money or a drink of vodka or schnapps.

The Neujahr (New Year) was also received with bells ringing at midnight. All the men in the village celebrated with great enthusiasm and noise-making.

Adults greeted each other on Silvestermorgen (the morning of New Year's Day). Traditionally, the first "visit" would start between four and five o'clock in the morning at the godparents' home, then they visited the in-laws, then aunts and uncles and friends.

Beginning in the mid-1800s, those greeting a family often fired their shotgun (decorated with ribbons and loaded with the smallest shot) into the air or at the front door to awaken the entire family. The greeter immediately opens the door and shouts "Good Morning" and then recognizes all of those present in the house, "Godfather and Godmother," "Uncle and Aunt Uncle," "Father-in-law and Mother-in-law," etc.

Then, the greeter recites a New Year's wish in the form of a poem, such as:

Ich wünsche Euch Glück zum neuen Jahr, Gesundheit, Friede und Einigkeit, ein lange Leben und nach Eurem Tode die ewige Seligkeit. (I wish you good luck for the New Year, health, peace and unity, a long life, and after your death, the eternal salvation of the soul.)

The praised homeowners would then thank the greeters with vodka, cold snacks of sausage, ham, and salt pork, and small gifts such as handkerchiefs.

All shooting in the colony stopped before the first ringing of the bells in the New Year, but the greetings continued:

Viel tausend Halleluja

Das ist mein Wunsch zum neuen Jahr

O Jesu mache alles wahr!

Many thousands of Hallelujah's

This is my wish for the New Year

Oh, Jesus, make everything right!

At five o'clock in the morning on New Year's day, all the young people went to congratulate their parents, grandparents, and the godparents on the arrival of the New Year. They recited a New Year poem they had been taught as small children:

Guten Morgen liebste Eltern,

den Freuden, wünsch ich auch zum neuen Jahr.

Gott wird eure Seel Versorgen.

Amen, ja es werde wahr!

Glück im Hause, Glück im Feld.

Gott ist alles heimgestellt.

So viel Glück und so viel Segen

als wie Tropfen in dem Regen,

alles Glück wird offenbar,

Amen, ja es werde wahr!

Good morning, dearest parents,

I wish you joy in the New Year.

May God nourish your soul.

Amen, yes, it will come true!

Happiness in the house, luck in the field.

God has made everything in the home.

So much happiness and many blessings

like drops of rain,

all happiness is revealed,

Amen, yes, it will come true!

The young people received copper coins or candy in thanks for their greetings.

The greetings continued until dawn, when the family would gather for the traditional New Year's breakfast of baked ham or mutton, thin pies, pastries, Krebble (a type of donut), and other special holiday foods. Prayers were said before the meal began. During the meal, musicians arrived and greeted the household with their clarinets and flutes, playing folk and church songs. The musicians were treated to hospitality from the household and given money (from 30 kopecks to one ruble) in appreciation.

After lunch, at around 2:00 p.m., young people gathered for sledding on the streets, which continued into nightfall.

There was also a large New Year's Day dinner, which usually featured the winter courses of pork, homemade sausage, and potatoes. After the main courses were consumed, they enjoyed Riwwelkuchen, Krebble, Pfannkuchen, Krümelkuchen (Zuckerkuchen), and special teas such as Süßholztee, Steppentee, and Schwarztee, which were expensive and reserved for the holidays. They also enjoy kvass, fruit coffees, and a unique caffeine-free coffee substitute called prips, made from roasted cereal grain. Of course, large quantities of vodka, schnapps, beer, and wine were also consumed while toasts such as Zur Gesundheit! (To your health!), were made, and folk songs were sung.

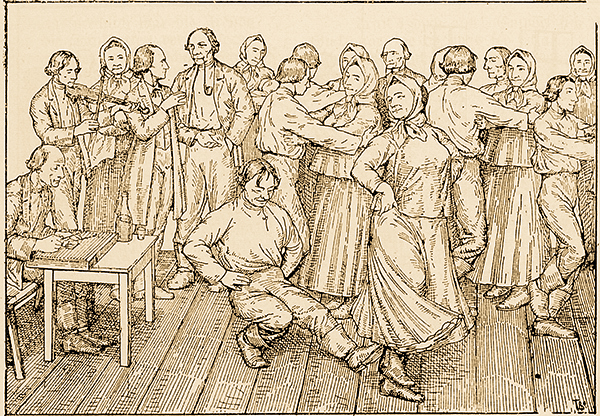

After dinner, young people skated on frozen ponds until nightfall and then gathered in homes vacated by the adults to play music, sing, and dance. Adults met in other homes to enjoy many of the same activities as the young people.

Late into the evening, everyone went home to sleep, content in knowing that the New Year was off to a good start.

As the worship service ended, the bells in the tower rang loudly, signaling a farewell to the old year.

In Norka, the Christkind (a young woman representing the Christ Child) appeared as she did on Weihnachten (Christmas). The Neujahrsmann (the New Year's Man) also visited the village on this holiday. The Neujahrsmann tradition was brought from the colonists' homelands in the 1760s. This character went from house to house and wished the residents good luck and blessings in the coming year. In return, he received a small token of money or a drink of vodka or schnapps.

The Neujahr (New Year) was also received with bells ringing at midnight. All the men in the village celebrated with great enthusiasm and noise-making.

Adults greeted each other on Silvestermorgen (the morning of New Year's Day). Traditionally, the first "visit" would start between four and five o'clock in the morning at the godparents' home, then they visited the in-laws, then aunts and uncles and friends.

Beginning in the mid-1800s, those greeting a family often fired their shotgun (decorated with ribbons and loaded with the smallest shot) into the air or at the front door to awaken the entire family. The greeter immediately opens the door and shouts "Good Morning" and then recognizes all of those present in the house, "Godfather and Godmother," "Uncle and Aunt Uncle," "Father-in-law and Mother-in-law," etc.

Then, the greeter recites a New Year's wish in the form of a poem, such as:

Ich wünsche Euch Glück zum neuen Jahr, Gesundheit, Friede und Einigkeit, ein lange Leben und nach Eurem Tode die ewige Seligkeit. (I wish you good luck for the New Year, health, peace and unity, a long life, and after your death, the eternal salvation of the soul.)

The praised homeowners would then thank the greeters with vodka, cold snacks of sausage, ham, and salt pork, and small gifts such as handkerchiefs.

All shooting in the colony stopped before the first ringing of the bells in the New Year, but the greetings continued:

Viel tausend Halleluja

Das ist mein Wunsch zum neuen Jahr

O Jesu mache alles wahr!

Many thousands of Hallelujah's

This is my wish for the New Year

Oh, Jesus, make everything right!

At five o'clock in the morning on New Year's day, all the young people went to congratulate their parents, grandparents, and the godparents on the arrival of the New Year. They recited a New Year poem they had been taught as small children:

Guten Morgen liebste Eltern,

den Freuden, wünsch ich auch zum neuen Jahr.

Gott wird eure Seel Versorgen.

Amen, ja es werde wahr!

Glück im Hause, Glück im Feld.

Gott ist alles heimgestellt.

So viel Glück und so viel Segen

als wie Tropfen in dem Regen,

alles Glück wird offenbar,

Amen, ja es werde wahr!

Good morning, dearest parents,

I wish you joy in the New Year.

May God nourish your soul.

Amen, yes, it will come true!

Happiness in the house, luck in the field.

God has made everything in the home.

So much happiness and many blessings

like drops of rain,

all happiness is revealed,

Amen, yes, it will come true!

The young people received copper coins or candy in thanks for their greetings.

The greetings continued until dawn, when the family would gather for the traditional New Year's breakfast of baked ham or mutton, thin pies, pastries, Krebble (a type of donut), and other special holiday foods. Prayers were said before the meal began. During the meal, musicians arrived and greeted the household with their clarinets and flutes, playing folk and church songs. The musicians were treated to hospitality from the household and given money (from 30 kopecks to one ruble) in appreciation.

After lunch, at around 2:00 p.m., young people gathered for sledding on the streets, which continued into nightfall.

There was also a large New Year's Day dinner, which usually featured the winter courses of pork, homemade sausage, and potatoes. After the main courses were consumed, they enjoyed Riwwelkuchen, Krebble, Pfannkuchen, Krümelkuchen (Zuckerkuchen), and special teas such as Süßholztee, Steppentee, and Schwarztee, which were expensive and reserved for the holidays. They also enjoy kvass, fruit coffees, and a unique caffeine-free coffee substitute called prips, made from roasted cereal grain. Of course, large quantities of vodka, schnapps, beer, and wine were also consumed while toasts such as Zur Gesundheit! (To your health!), were made, and folk songs were sung.

After dinner, young people skated on frozen ponds until nightfall and then gathered in homes vacated by the adults to play music, sing, and dance. Adults met in other homes to enjoy many of the same activities as the young people.

Late into the evening, everyone went home to sleep, content in knowing that the New Year was off to a good start.

The following YouTube video shows a modern-day Neujahrsmann making his rounds in Oberkalbach, Germany. Oberkalbach is located in the same geographic area where many families from Norka lived before emigrating to Russia in 1766.

Listen to a recording of a Volga German New Year's wish (GFR0049.mp3) spoken by Mrs. John P. Geringer, courtesy of the Colorado State University, Sidney Heitman Germans from Russia Collection.

Sources

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Printed by Augstums Printing Service, 2005. Print.

Erina, E. M., and V. E. Salʹkova. Obychai Povolzhskikh Nemt︠s︡ev = Sitten Und Bräuche Der Wolgadeutschen. Moskva: Gotika, 2000. Print.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums." Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): 152. Print.

Erina, E. M., and V. E. Salʹkova. Obychai Povolzhskikh Nemt︠s︡ev = Sitten Und Bräuche Der Wolgadeutschen. Moskva: Gotika, 2000. Print.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums." Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): 152. Print.

Last updated November 28, 2023