Traditions > Holidays > Christmas and the Advent Season

Christmas and the Advent Season

Weihnachten (Christmas) was the most eagerly anticipated religious and social festival in Norka. It was a time to observe old traditions from the German homeland that were influenced by the environment on the Lower Volga.

Advent, the beginning of the church year, starts on the fourth Sunday before December 25. With the arrival of Advent Sunday, the Christmas season officially began.

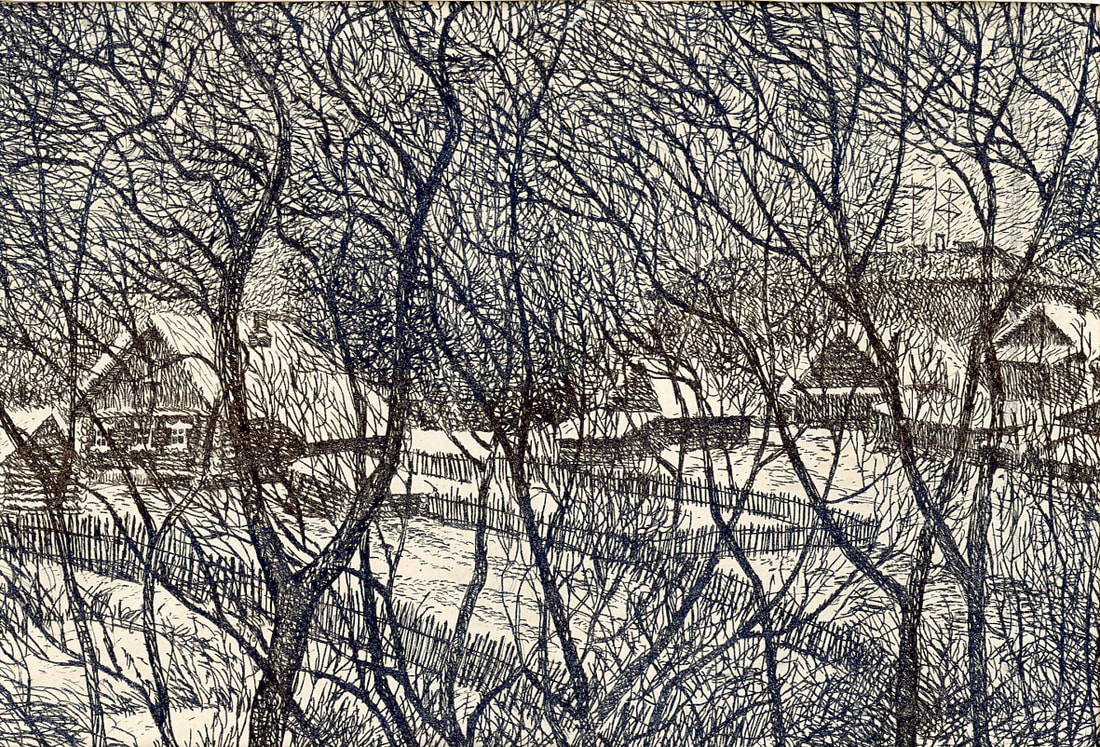

Weather during December was usually cold, with average temperatures ranging from lows in the mid-teens to highs in the mid-20s Fahrenheit. Light to moderate snow fell most days throughout the month, and the colony would often be wrapped in a white blanket.

Homes and yards were thoroughly cleaned, and anything that could dampen or restrain the seasonal spirit was eliminated. A comprehensive cleaning took place on the Saturday before Christmas. Pastor Eduard Seib reported that men often had to leave the house because the cleaning devil took possession of the women, transforming them into Lappenvolk (the dustrag people). The house, the yard, and the street in front of the house were swept thoroughly. Weather permitting, the exteriors of the homes were whitewashed. Fresh clothing was readied, and boots and shoes were polished.

With the cleaning completed, homes could then be decorated. Evergreens had long been a part of the Christmas tradition for the German colonists, but none were found in the steppe surrounding Norka. Undeterred, the colonists decorated the interior of their homes with as much greenery as possible: wheat sprouts, barley, branches of lilacs, cherries, and cornel were cut well in advance and set in water in a warm place so they would bud and bloom by Christmas. If this failed, the branches were decorated with colorful paper flowers and chains fashioned by the children.

Advent, the beginning of the church year, starts on the fourth Sunday before December 25. With the arrival of Advent Sunday, the Christmas season officially began.

Weather during December was usually cold, with average temperatures ranging from lows in the mid-teens to highs in the mid-20s Fahrenheit. Light to moderate snow fell most days throughout the month, and the colony would often be wrapped in a white blanket.

Homes and yards were thoroughly cleaned, and anything that could dampen or restrain the seasonal spirit was eliminated. A comprehensive cleaning took place on the Saturday before Christmas. Pastor Eduard Seib reported that men often had to leave the house because the cleaning devil took possession of the women, transforming them into Lappenvolk (the dustrag people). The house, the yard, and the street in front of the house were swept thoroughly. Weather permitting, the exteriors of the homes were whitewashed. Fresh clothing was readied, and boots and shoes were polished.

With the cleaning completed, homes could then be decorated. Evergreens had long been a part of the Christmas tradition for the German colonists, but none were found in the steppe surrounding Norka. Undeterred, the colonists decorated the interior of their homes with as much greenery as possible: wheat sprouts, barley, branches of lilacs, cherries, and cornel were cut well in advance and set in water in a warm place so they would bud and bloom by Christmas. If this failed, the branches were decorated with colorful paper flowers and chains fashioned by the children.

Preparations also began for the traditional Christmas meals. Women cooked and baked Christmas cookies and pastries. One appealing folk belief was that a red sky at sunset on the days before Christmas meant that the angels were busy baking cookies.

Even some of the animals must have looked forward to Christmas. In many Volga German homes, it was a custom to bake an extra loaf of bread for the cat and dog. Bad luck could result if the family forgot to bake this gift for their pets.

The men carved small wooden toys for the children, and the women sewed, knitted, and crocheted. With so much preparation work, the adults had no time left over for children who were often minded by their grandmother. The grandmothers taught the children traditional songs, and their voices resounded throughout the house.

During the evening of Advent Sunday, outside on the streets, there was a rattling of chains, ringing of cowbells, and shrill whistles which became louder and louder. From the dark shadows appeared a crowd of boys and unmarried young men. At the head of the pack was the large, black, shaggy shape of the Pelznickel (also Belznickel). The old tradition of the Pelznickel as a dark figure acting as a servant of Sankt Nikolas (St. Nicholas) was blurred with St. Nicholas, especially in Reformed faith regions of Germany where many of the original colonists had lived before settling in Norka.

If disobedient boys were in the house, the Pelznickel was often called in. The boys were frequently warned about him during the year. They were told if they weren't behaving, Der Pelznickel kommt! (the Pelznickel will come for you!).

The Pelznickel was usually a muscular young fellow with a deep bass voice who wore a black sheepskin coat turned inside out, a fur hat made of the same material, an unkempt costume beard, and enormous felt boots. His shirt was stuffed to make him appear more imposing. He wrapped a long clattering chain over his shoulder and carried a ragged sack in his left hand and a bundle of switches or a whip in his right hand. In such an outfit, reminding one of the devil himself, he stepped over the threshold into the house, rattling his chain, wringing cries of fear and terror from the bad boys, who all attempted to hide under tables and beds. The Pelznickel would then choose one of the unfortunate fellows who would be dragged from their hiding places and asked to give an account of their transgressions (obtained beforehand from the parents). Sometimes, the Pelznickel didn't say much but let the sound of his switch bring the message. Its echo remained in the ears of the boys for a long time. Sometimes, the Pelznickel would ask questions about the Bible. Only after extracting correct answers and promises from the children to never misbehave, to study hard, and to respect their parents did the Pelznickel put away his whip and depart into the dark night with his entourage.

Even some of the animals must have looked forward to Christmas. In many Volga German homes, it was a custom to bake an extra loaf of bread for the cat and dog. Bad luck could result if the family forgot to bake this gift for their pets.

The men carved small wooden toys for the children, and the women sewed, knitted, and crocheted. With so much preparation work, the adults had no time left over for children who were often minded by their grandmother. The grandmothers taught the children traditional songs, and their voices resounded throughout the house.

During the evening of Advent Sunday, outside on the streets, there was a rattling of chains, ringing of cowbells, and shrill whistles which became louder and louder. From the dark shadows appeared a crowd of boys and unmarried young men. At the head of the pack was the large, black, shaggy shape of the Pelznickel (also Belznickel). The old tradition of the Pelznickel as a dark figure acting as a servant of Sankt Nikolas (St. Nicholas) was blurred with St. Nicholas, especially in Reformed faith regions of Germany where many of the original colonists had lived before settling in Norka.

If disobedient boys were in the house, the Pelznickel was often called in. The boys were frequently warned about him during the year. They were told if they weren't behaving, Der Pelznickel kommt! (the Pelznickel will come for you!).

The Pelznickel was usually a muscular young fellow with a deep bass voice who wore a black sheepskin coat turned inside out, a fur hat made of the same material, an unkempt costume beard, and enormous felt boots. His shirt was stuffed to make him appear more imposing. He wrapped a long clattering chain over his shoulder and carried a ragged sack in his left hand and a bundle of switches or a whip in his right hand. In such an outfit, reminding one of the devil himself, he stepped over the threshold into the house, rattling his chain, wringing cries of fear and terror from the bad boys, who all attempted to hide under tables and beds. The Pelznickel would then choose one of the unfortunate fellows who would be dragged from their hiding places and asked to give an account of their transgressions (obtained beforehand from the parents). Sometimes, the Pelznickel didn't say much but let the sound of his switch bring the message. Its echo remained in the ears of the boys for a long time. Sometimes, the Pelznickel would ask questions about the Bible. Only after extracting correct answers and promises from the children to never misbehave, to study hard, and to respect their parents did the Pelznickel put away his whip and depart into the dark night with his entourage.

The High Christmas Festival lasted three days, and during that time, all the chores were suspended except for the care of the animals.

The house became calm after a large midday lunch on Heiligabend (Christmas Eve). Children prepared for their worship service, which began at about 4 p.m. When the church bells rang, the children hurried through the streets to find their place inside the Norka church. The church, with 2,500 seats, was the pride of the colony. Despite its modest furnishings, the building made a great impression on the congregation. Children were greeted by the sight of a large Christmas tree decorated with candles and toys. For the children's Christmas service, the church was always filled. A Christmas pageant was performed, and the children recited poems and sang Christmas songs led by the Schulmeister (Schoolmaster). With joy and emotion, they saw the Nativity scene standing under the tree. The children's hearts were illuminated with joy and a deep faith in this miracle of God.

After the service, each child received a small gift from under the tree, usually a sack filled with gingerbreads and paper-wrapped candies. Though the gift was modest, the children were always sincerely appreciative. After the service, they bustled home under the dark sky dotted with bright stars. The streets were illuminated by torches or barrels of burning kerosene that were placed to guide their way. The cheerful sounds of the Christmettglocken (Christmas bells) filled the air. They reunited with their parents at home in the warm and cozy house.

The children greatly anticipated whether or not the Christkind (a young woman representing Christ Child) would come to the house later that evening.

At 7 p.m., the bells chimed and summoned the adults to church for the service to honor the Christ Child. They marched to the church in their finest clothes and with the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga hymnal) in their hands. Only a few people remained at home to babysit the little ones.

Again, the church was filled to standing room only. The giant Christmas tree pleased the diligent and respectable farmers who had labored for long hours in their fields. At this time of year, they rested and praised God, thanking Him for answering their prayers. Before manufactured ornaments were available, crescents, stars, animals, bells, and other handmade objects were used as decorations. Baked cookies shaped like stars, animals, and other familiar objects were also used to trim the tree, along with firm and fresh apples from the cellar. Most spectacular were the many glowing candles attached to the branches, illuminating the tree and ornaments. Crowning the top of the tree was a ring of angels, which revolved as heat rose from the candles.

Following the church service, the parents returned home to their children, who were eagerly anticipating the arrival of the Christkind.

The house became calm after a large midday lunch on Heiligabend (Christmas Eve). Children prepared for their worship service, which began at about 4 p.m. When the church bells rang, the children hurried through the streets to find their place inside the Norka church. The church, with 2,500 seats, was the pride of the colony. Despite its modest furnishings, the building made a great impression on the congregation. Children were greeted by the sight of a large Christmas tree decorated with candles and toys. For the children's Christmas service, the church was always filled. A Christmas pageant was performed, and the children recited poems and sang Christmas songs led by the Schulmeister (Schoolmaster). With joy and emotion, they saw the Nativity scene standing under the tree. The children's hearts were illuminated with joy and a deep faith in this miracle of God.

After the service, each child received a small gift from under the tree, usually a sack filled with gingerbreads and paper-wrapped candies. Though the gift was modest, the children were always sincerely appreciative. After the service, they bustled home under the dark sky dotted with bright stars. The streets were illuminated by torches or barrels of burning kerosene that were placed to guide their way. The cheerful sounds of the Christmettglocken (Christmas bells) filled the air. They reunited with their parents at home in the warm and cozy house.

The children greatly anticipated whether or not the Christkind (a young woman representing Christ Child) would come to the house later that evening.

At 7 p.m., the bells chimed and summoned the adults to church for the service to honor the Christ Child. They marched to the church in their finest clothes and with the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga hymnal) in their hands. Only a few people remained at home to babysit the little ones.

Again, the church was filled to standing room only. The giant Christmas tree pleased the diligent and respectable farmers who had labored for long hours in their fields. At this time of year, they rested and praised God, thanking Him for answering their prayers. Before manufactured ornaments were available, crescents, stars, animals, bells, and other handmade objects were used as decorations. Baked cookies shaped like stars, animals, and other familiar objects were also used to trim the tree, along with firm and fresh apples from the cellar. Most spectacular were the many glowing candles attached to the branches, illuminating the tree and ornaments. Crowning the top of the tree was a ring of angels, which revolved as heat rose from the candles.

Following the church service, the parents returned home to their children, who were eagerly anticipating the arrival of the Christkind.

The role of Christkind was usually played by a young woman with a pleasant, clear voice and a sense of humor. She was dressed in white with a veil over her face to hide her identity. In her hands, she carried a burning candle. Dressed this way and accompanied by several other unmarried girls, she appeared at the window of a house after the lamps were lit. One of her companions rang a bell in front of a window, and the Christkind asked: "May the Christkind come in?" When the lady of the house answered, "Eino, kommt rein! (Come in!)," the Christkind and her entourage entered the house. They were quickly whisked off to the kitchen, where one of the mothers filled her apron with an assortment of baked goods and delicacies, sometimes wrapped in a red handkerchief. The gifts would be distributed to the children at the appropriate time. Then the Christkind was shown to the family room where the children chanted:

Christkind, liebes Herz. Was hast du unter deinem Scherz? . . . (Christ child, oh dear Christ child. What gifts do you have under your apron for us? . . .)

Now, the Christkind began her examination of each child: Do you say your prayers faithfully? Do you obey your parents? And so on. The children were also asked to recite a prayer to prove their knowledge. After positive responses to the questioning, the children received their gifts, which could also include hand-sewn gifts of small apparel, a sweet from the local store, a wooden pencil box, or carving. Although these gifts were presented without wrapping, ribbon, or bows, the children were thrilled to receive them. With the children distracted by the gifts, the Christkind and her entourage made a quick exit as they had many homes to visit that night.

The Christkind only paid visits to well-behaved children, and parents no doubt used this opportunity to speak to each child about their bad habits or mistakes. The children promised to make an effort to do better in the coming year and prepared for bed, feeling tired but reveling in anticipation of the events to come.

Christkind, liebes Herz. Was hast du unter deinem Scherz? . . . (Christ child, oh dear Christ child. What gifts do you have under your apron for us? . . .)

Now, the Christkind began her examination of each child: Do you say your prayers faithfully? Do you obey your parents? And so on. The children were also asked to recite a prayer to prove their knowledge. After positive responses to the questioning, the children received their gifts, which could also include hand-sewn gifts of small apparel, a sweet from the local store, a wooden pencil box, or carving. Although these gifts were presented without wrapping, ribbon, or bows, the children were thrilled to receive them. With the children distracted by the gifts, the Christkind and her entourage made a quick exit as they had many homes to visit that night.

The Christkind only paid visits to well-behaved children, and parents no doubt used this opportunity to speak to each child about their bad habits or mistakes. The children promised to make an effort to do better in the coming year and prepared for bed, feeling tired but reveling in anticipation of the events to come.

On Christmas morning, the children woke up later after an eventful night and spent some time chatting in bed. Then their mother called them to the morning meal where she served Riwwelkuchen (also called Sträußelkuchen or Streuselkuchen), Pfeffernüßchen or other holiday treats.

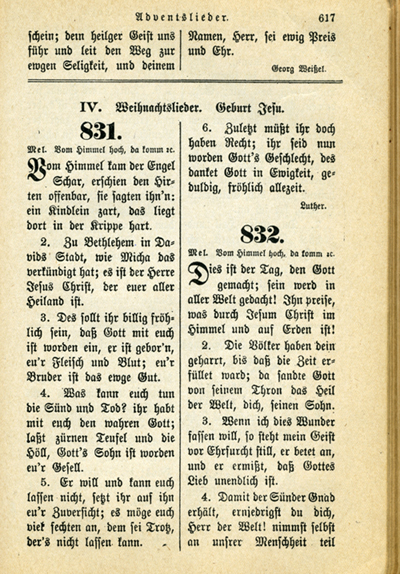

After the morning meal, the adults attended a church service at 9 a.m. Though they had heard it many times before, everyone enjoyed the story of the birth of Jesus, which was read from Luke 2:1-20. There was a strong sense of community when they sang together the traditional Weihnachtslieder (Christmas songs) from the Wolga Gesangbuch such as Von Himmel Hoch, Da Komm' Ich Her, Number 831 (From Heaven Above to Earth I Come - text by Martin Luther) and Nun Danket Alle Gott, Number 107 (Now Thank We All Our God). The people of Norka, as was typical amongst the Volga Germans, sang from their hearts with great enthusiasm.

After the morning meal, the adults attended a church service at 9 a.m. Though they had heard it many times before, everyone enjoyed the story of the birth of Jesus, which was read from Luke 2:1-20. There was a strong sense of community when they sang together the traditional Weihnachtslieder (Christmas songs) from the Wolga Gesangbuch such as Von Himmel Hoch, Da Komm' Ich Her, Number 831 (From Heaven Above to Earth I Come - text by Martin Luther) and Nun Danket Alle Gott, Number 107 (Now Thank We All Our God). The people of Norka, as was typical amongst the Volga Germans, sang from their hearts with great enthusiasm.

While the adults worshipped, the children rode their sleds down the street or a nearby hill.

Later on Christmas Day, family dinners were held with great quantities of food and drink. Gift exchange between adults was not customary. The children delivered cookies called Brenich to their Godparents. One of the children's treats was a konfekt (candy) wrapped in paper. On the paper was a colorful picture, and the girls saved these wrappers.

Much visiting was carried on in the homes of family and friends. In the evening, the young ladies would gather at a chosen home, and the young men would ride by with their finest horses harnessed to the family sleigh to catch the girls' attention.

Before midnight, the children watched their fathers quietly put on a heavy coat and go outside to tend to the animals. The children were told of an old superstition that the animals could speak with a human voice at midnight on Christmas and New Year's.

At midnight, many older folks went caroling from house to house. They would sing two or three pieces, then knock at the window and call: "For you, today is born the Savior; celebrate with us!" The families with larger homes would invite the carolers in for hot tea, coffee cake, and pastries.

The Christmas season was also a time of weddings. Many marriages took place during the week between Christmas and the Neujahrsfeier (New Year's celebration). The traditional wedding date was the second day of Christmas (December 26th), when multiple couples would gather to take their marriage vows.

In his book The Volga Germans, Fred Koch beautifully captures the spirit of a Volga German Christmas:

Later on Christmas Day, family dinners were held with great quantities of food and drink. Gift exchange between adults was not customary. The children delivered cookies called Brenich to their Godparents. One of the children's treats was a konfekt (candy) wrapped in paper. On the paper was a colorful picture, and the girls saved these wrappers.

Much visiting was carried on in the homes of family and friends. In the evening, the young ladies would gather at a chosen home, and the young men would ride by with their finest horses harnessed to the family sleigh to catch the girls' attention.

Before midnight, the children watched their fathers quietly put on a heavy coat and go outside to tend to the animals. The children were told of an old superstition that the animals could speak with a human voice at midnight on Christmas and New Year's.

At midnight, many older folks went caroling from house to house. They would sing two or three pieces, then knock at the window and call: "For you, today is born the Savior; celebrate with us!" The families with larger homes would invite the carolers in for hot tea, coffee cake, and pastries.

The Christmas season was also a time of weddings. Many marriages took place during the week between Christmas and the Neujahrsfeier (New Year's celebration). The traditional wedding date was the second day of Christmas (December 26th), when multiple couples would gather to take their marriage vows.

In his book The Volga Germans, Fred Koch beautifully captures the spirit of a Volga German Christmas:

Despite environmental austerity, absence of commercialism, and apathy toward material objects, Christmas was a joyous season in the colonies; its social and religious purpose animated the community as it does in few Christian climates today. The sense of the holiday was captured in its spiritual essence rather than its ostentations.

Notes

Most of the colonists who settled in Norka originated from the Germanic areas of Hesse and Isenburg, which have a storied connection to the Christmas tree. Long before it was incorporated into the Christian tradition, the Solstice Evergreen was a common pagan symbol in many cultures worldwide, including medieval Hesse. The evergreen signified the persistence of new life amid the darkness of winter. Many scholars trace the origin of the Christmas tree custom to St. Boniface, an English Bishop who was a missionary in Hesse during the eighth century, working on converting the pagan Germans to Christianity. St. Boniface is credited with convincing the Germans to change their pagan beliefs. St. Boniface performed one his most notable acts of conversion, the felling of the Thor's Oak, in the area of Fritzlar. His remains rest in a sarcophagus in the nearby city of Fulda. When the oak tree fell, it was said that a fir tree appeared. Boniface proclaimed this a miracle and said the fir tree was the tree of life and represented Christ. By the 1600s, the Christmas tree custom had spread to the extent that some German families had trees in their homes.

With an axe in one hand, Winfrid (later Saint Boniface) holds a white crucifix over the fallen Thor's Oak while one of his attendants pray and the other solemnly holds an axe. The Chatti, a Germanic tribe, look on. An Emil Doepler painting, circa 1905. From the book Walhall, die Götterwelt der Germanen. Martin Oldenbourg, Berlin. Page 16. A Public Domain image from Wikimedia Commons.

According to Rev. Horst Gutsche, the Wolga Gesangbuch was first published in the early 1800s. Before this publication became the primary songbook for the Evangelischen (Evangelical) colonies, people would have likely used their own hymnals from their places of origin in the Germanic areas of Europe. Christmas hymns are found in the Wolga Gesangbuch from numbers 95 to 114 and 831 and 832.

Given the cold weather, unfamiliar environment, basic housing, and limited supplies, Christmas festivities in the first years of settlement were surely celebrations of thanks and survival.

It should be noted that the Christkind was not intended to represent the Christ Child literally but was more like a good fairy of the type found in old Germanic tales.

The Pelznickel (also Belznickel or Belsnickel) was a variation of the kind, gift-giving St. Nicholas. He was originally the companion of the pre-Reformation Nicholas, who punished children. The word Pelznickel roughly translates to "Pelts Nicholas" or "Nicholas in fur"). The Pelznickel tradition originated in southwestern Germany along the Rhine, the Saarland, and the Odenwald region of Baden-Württemberg. The Pelznickel is also a part of the Christmas tradition in the Pennsylvania Dutch communities. The Pelznickel was usually a bearded figure dressed in a brown or black sheepskin robe, wearing a belt, carrying a whip or bundle of switches in one hand, and carrying a bag in the other. Sometimes, the Pelznickel is portrayed bearing gifts in a basket on his back - mostly small bags filled with mandarin oranges, peanuts, chocolate, and gingerbread. This is likely the origin of the small gift sacks for children that continue into modern times. Curiously, the tradition of the Pelznickel does not seem to have been common in the Wetteraukreis and Main-Kinzig Kreis, where most of the Norka colonists originated. It is assumed that the colonists in Norka adopted this custom from those originating in other parts of Germanic Europe.

Brenich is a holiday cookie made by pressing dough onto a buttered board carved with designs. The individual cookies are cut apart after the dough has been baked. Old-timers used the last joint of a duck wing to butter the board in place of a pastry brush. Old Brenich boards are prized heirlooms in some Volga German families. (from Sei Unser Gast, page 156, published by the AHSGR North Star Chapter, 1996).

Given the cold weather, unfamiliar environment, basic housing, and limited supplies, Christmas festivities in the first years of settlement were surely celebrations of thanks and survival.

It should be noted that the Christkind was not intended to represent the Christ Child literally but was more like a good fairy of the type found in old Germanic tales.

The Pelznickel (also Belznickel or Belsnickel) was a variation of the kind, gift-giving St. Nicholas. He was originally the companion of the pre-Reformation Nicholas, who punished children. The word Pelznickel roughly translates to "Pelts Nicholas" or "Nicholas in fur"). The Pelznickel tradition originated in southwestern Germany along the Rhine, the Saarland, and the Odenwald region of Baden-Württemberg. The Pelznickel is also a part of the Christmas tradition in the Pennsylvania Dutch communities. The Pelznickel was usually a bearded figure dressed in a brown or black sheepskin robe, wearing a belt, carrying a whip or bundle of switches in one hand, and carrying a bag in the other. Sometimes, the Pelznickel is portrayed bearing gifts in a basket on his back - mostly small bags filled with mandarin oranges, peanuts, chocolate, and gingerbread. This is likely the origin of the small gift sacks for children that continue into modern times. Curiously, the tradition of the Pelznickel does not seem to have been common in the Wetteraukreis and Main-Kinzig Kreis, where most of the Norka colonists originated. It is assumed that the colonists in Norka adopted this custom from those originating in other parts of Germanic Europe.

Brenich is a holiday cookie made by pressing dough onto a buttered board carved with designs. The individual cookies are cut apart after the dough has been baked. Old-timers used the last joint of a duck wing to butter the board in place of a pastry brush. Old Brenich boards are prized heirlooms in some Volga German families. (from Sei Unser Gast, page 156, published by the AHSGR North Star Chapter, 1996).

A traditional Volga German Christmas song was Es ist ein Ros' entsprungen (Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming) written in 1599. Stille Nacht (Silent Night) was written after the German migration to the Volga region between 1764 and 1766. Nevertheless, it became a traditional favorite in later years. You can enjoy performances of both songs by The King's Singers below and examples of other traditional Christmas songs sung by those who lived in Norka.

|

|

|

|

|

|

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks officially banned Christmas celebrations. In Norka, Christmas celebrations continued until the church was closed in the 1930s during Stalin's Reign of Terror.

Sources

Bachmann, Eugen. "German Christmas in Siberia." American Historical Society of Germans from Russia Work Paper No. 16 (1974): 43-44. Print.

Geisinger, Adam. "There Was No Santa Claus in Russia." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 5.4 (1982): 1-2. Print.

"Interview of Elizabeth Burbach and Katherine Rudolph (both born in Norka - now deceased)." Interview by William Burbach. 1980. Milwaukie, Oregon. Transcript provided to Steven H. Schriber. Portland, Oregon.

"Interviews about the Village of Brunnental, Russia (Kriwojar in Russian) with Maria (Lebsack) Becker who was born in Brunnental." Interviews by Marie (Greenwald) Bandey. 1978-1982. <http://www.brunnental.us/brunnental/intrview.txt>

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 192-94. Print.

Müthel, Edith, "Christmas in Norka Colony on the Volga." Der Bote. № 4, 1997. 11. A publication of the Evangelical Church of Russia (Russian Language).

Olson, Marie Miller., and Anna Miller. Reisbick. Norka, a German Village in Russia. Denver: S.n., 1981. 22. Print.

Seebach, Helmut. "Odenwälder Brauchtum". Weinheim: Edition Diesbach, 2002. p. 86.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums." Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): Print.

Sinner, Peter. "Deutsche Weihnacht bei den Wolgakolonisten - Der Jugend erzhält" (German Language). Deutsche Post aus dem Osten, (1928), Heft 12, 253-255.

Yerina, Elizabeth M. "Christmas and Other Traditional Holidays of the Germans on the Volga." Trans. Rick Rye. Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 21.3 (1998): 7-12. Print.

Yerina, Elizabeth. M., and V. E. Salʹkova. Sitten und Bräuche der Wolgadeutschen. Moskva: Gotika, 2000. Print.

Geisinger, Adam. "There Was No Santa Claus in Russia." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 5.4 (1982): 1-2. Print.

"Interview of Elizabeth Burbach and Katherine Rudolph (both born in Norka - now deceased)." Interview by William Burbach. 1980. Milwaukie, Oregon. Transcript provided to Steven H. Schriber. Portland, Oregon.

"Interviews about the Village of Brunnental, Russia (Kriwojar in Russian) with Maria (Lebsack) Becker who was born in Brunnental." Interviews by Marie (Greenwald) Bandey. 1978-1982. <http://www.brunnental.us/brunnental/intrview.txt>

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 192-94. Print.

Müthel, Edith, "Christmas in Norka Colony on the Volga." Der Bote. № 4, 1997. 11. A publication of the Evangelical Church of Russia (Russian Language).

Olson, Marie Miller., and Anna Miller. Reisbick. Norka, a German Village in Russia. Denver: S.n., 1981. 22. Print.

Seebach, Helmut. "Odenwälder Brauchtum". Weinheim: Edition Diesbach, 2002. p. 86.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums." Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): Print.

Sinner, Peter. "Deutsche Weihnacht bei den Wolgakolonisten - Der Jugend erzhält" (German Language). Deutsche Post aus dem Osten, (1928), Heft 12, 253-255.

Yerina, Elizabeth M. "Christmas and Other Traditional Holidays of the Germans on the Volga." Trans. Rick Rye. Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 21.3 (1998): 7-12. Print.

Yerina, Elizabeth. M., and V. E. Salʹkova. Sitten und Bräuche der Wolgadeutschen. Moskva: Gotika, 2000. Print.

Last updated December 15, 2023