The First Christmas in Norka, Russia

Written by Steve Schreiber

On Christmas Day in 1767, Johann Wilhelm Schreiber and his wife Anna Eva (her maiden name was Moritz) were celebrating Christmas for the first time in Norka, Russia. More than a year earlier, they had decided to leave their homes in Hessen for what they hoped would be a better life in a new land.

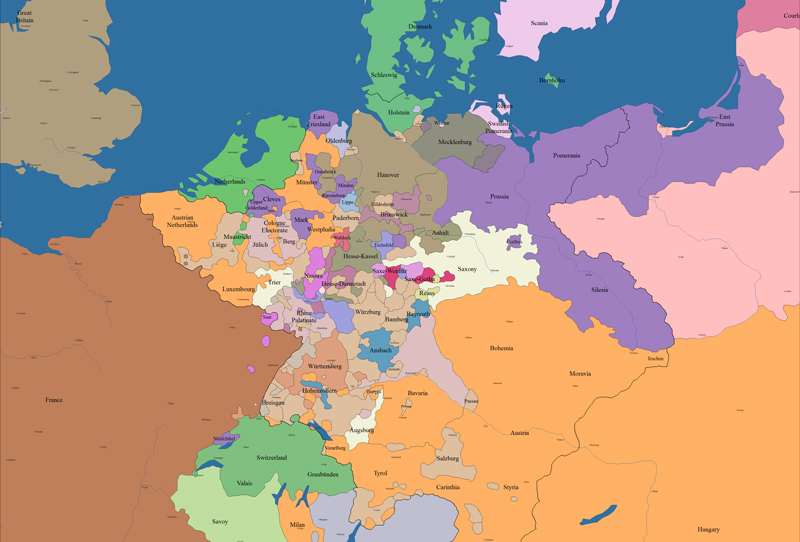

The area where they lived had been decimated during the Thirty Years and Seven Year's Wars that ravaged much of this part of Central Europe. The Seven Year's War (1756-1763) is referred to by many historians as the true "first world war" which resulted in 900,000 to 1,400,000 deaths. The two ruling houses of Hesse were divided in this struggle and their subjects were often forced to serve in the military and to pay higher taxes to support the war. Many Hessians were coerced into military conscription to serve as mercenaries fighting in other nation's wars. In later years, these Hessian soldiers would be involved in the Revolutionary War between Great Britain and the thirteen British colonies in North America. Johann Wilhelm's father was a master carpenter, but also served in the Prinz Georg Regiment as a musketeer. He had no doubt seen the terrible impacts of war and that experience was probably shared with Johann Wilhelm.

The area where they lived had been decimated during the Thirty Years and Seven Year's Wars that ravaged much of this part of Central Europe. The Seven Year's War (1756-1763) is referred to by many historians as the true "first world war" which resulted in 900,000 to 1,400,000 deaths. The two ruling houses of Hesse were divided in this struggle and their subjects were often forced to serve in the military and to pay higher taxes to support the war. Many Hessians were coerced into military conscription to serve as mercenaries fighting in other nation's wars. In later years, these Hessian soldiers would be involved in the Revolutionary War between Great Britain and the thirteen British colonies in North America. Johann Wilhelm's father was a master carpenter, but also served in the Prinz Georg Regiment as a musketeer. He had no doubt seen the terrible impacts of war and that experience was probably shared with Johann Wilhelm.

When the Russian government of Catherine II (Catherine "The Great") published its Manifesto in 1763 encouraging settlement in Russia, over 30,000 people chose to emigrate. The Manifesto promised free land, no taxes, freedom of religion and no military conscription. This was an offer that many Hessians, including Johann Wilhelm, found hard to resist. The majority of the colonists were drawn from the Germanic areas of Central Europe. Catherine's goal was to to settle the eastern frontier of Russia with experienced craftsmen and farmers from Western Europe who would bring stability to an area that was influenced by nomadic Asian tribes and bands of outlaws. Catherine also hoped that the colonists would serve as models for the Russian peasants who were using wooden plows and primitive farming techniques. Of course, Russia was not alone in encouraging immigration during this time period. Many Hessians and other Germanic people were also migrating to the British colonies in North America.

Johann Wilhelm left his comfortable home in Ronshausen at the age of 17, likely with members of the Bäcker (Becker) family who lived in the same town. His family owned a water powered sawmill and most of the men were master carpenters. Wilhelm had three older brothers and one of them would likely become the owner of the mill when their father was no longer able to do this work. Johann Wilhelm's parents may have encouraged him to leave Ronshausen to avoid military conscription and to find a better life in a new land.

The group of families from Ronshausen traveled to a recruiting center in the city of Büdingen. It appears that Johann Wilhelm posed as a son of one of the Beckers and temporarily changed his name since he was not of age to sign an agreement with the Russian recruiters or to be married.

The Russian recruiters preferred married couples. Like many other would be colonists, Johann Wilhelm married Anna Eva Moritz on May 7, 1766 in the Büdingen St. Mary's Church (Marienkirche). Anna Eva's parents were also migrating to Russia.

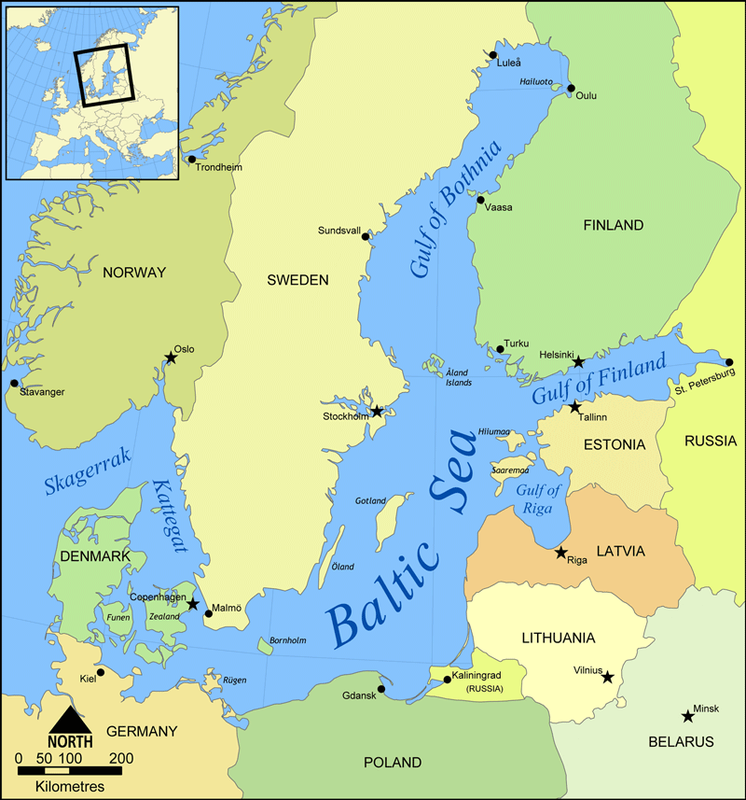

In Büdingen the colonists were organized into transport groups by the Russian government and private recruiters. From the gathering point, Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva probably traveled to the Hanseatic port of Lübeck on the Baltic Sea where they waited for a transport ship that would carry them to the Russian empire. This would be the journey of a lifetime for the two young people from rural Hessen who had likely never been far from home.

Johann Wilhelm left his comfortable home in Ronshausen at the age of 17, likely with members of the Bäcker (Becker) family who lived in the same town. His family owned a water powered sawmill and most of the men were master carpenters. Wilhelm had three older brothers and one of them would likely become the owner of the mill when their father was no longer able to do this work. Johann Wilhelm's parents may have encouraged him to leave Ronshausen to avoid military conscription and to find a better life in a new land.

The group of families from Ronshausen traveled to a recruiting center in the city of Büdingen. It appears that Johann Wilhelm posed as a son of one of the Beckers and temporarily changed his name since he was not of age to sign an agreement with the Russian recruiters or to be married.

The Russian recruiters preferred married couples. Like many other would be colonists, Johann Wilhelm married Anna Eva Moritz on May 7, 1766 in the Büdingen St. Mary's Church (Marienkirche). Anna Eva's parents were also migrating to Russia.

In Büdingen the colonists were organized into transport groups by the Russian government and private recruiters. From the gathering point, Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva probably traveled to the Hanseatic port of Lübeck on the Baltic Sea where they waited for a transport ship that would carry them to the Russian empire. This would be the journey of a lifetime for the two young people from rural Hessen who had likely never been far from home.

The voyage across the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Finland would have taken weeks or possibly months in some cases. Unscrupulous merchants would sometimes intentionally delay arrival in Russia to extract more money from the colonists for food and other necessities.

After the Schreiber's arrival in Russia at the port of Oranienbaum on August 9, 1766, they may have assembled at the Summer Palace where the Czarina would, on occasion, greet the new arrivals in their native German language. The sight of Catherine and her magnificent palace must have impressed the young Hessian emigrants. However, this impression would not be typical of what they would experience in a country that was decades behind Western Europe in its development.

While in Oranienbaum, Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva were housed in barracks and registered by the special commissar, Ivan Kulberg, who oversaw the emigration process. All of colonists were led by the local Lutheran German pastor in swearing an oath of allegiance to Catherine II and their new country.

After the Schreiber's arrival in Russia at the port of Oranienbaum on August 9, 1766, they may have assembled at the Summer Palace where the Czarina would, on occasion, greet the new arrivals in their native German language. The sight of Catherine and her magnificent palace must have impressed the young Hessian emigrants. However, this impression would not be typical of what they would experience in a country that was decades behind Western Europe in its development.

While in Oranienbaum, Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva were housed in barracks and registered by the special commissar, Ivan Kulberg, who oversaw the emigration process. All of colonists were led by the local Lutheran German pastor in swearing an oath of allegiance to Catherine II and their new country.

After completing their processing in Oranienbaum, the Schreiber's were transported to nearby St. Petersburg where they remained on ship for as long as three weeks. From this point, they were formed into convoys, led by military officers, bound for their settlement sites on the lower Volga near Saratov. Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva could not have known how long and difficult the next part of the journey would be.

After departing from St. Petersburg, the ships proceeded 45 miles up the Neva River, through the Schlüsselburg Canal around Lake Lagoda and then to the mouth of the Sivr River and upriver to Lake Onega. The colonists then sailed out of Lake Onega into the Vytegra River and then down the Kovzha River to Beloye (White) Lake. At the time, there was likely a short overland portage at this point in the journey between the Vytegra River and the Kovzha River (the two rivers are now joined by a canal). The portage was accomplished by horse drawn wagon. Women, children and baggage were loaded aboard the wagons and the able bodied men walked.

At the southeast edge of White Lake they entered the Sheksna River which flows into the Volga River at Rybinsk.

Given that the Volga River freezes for most of its length for three months each year, it is likely that Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva spent their first winter and Christmas with Russian peasant families in or near Sheksna.

After departing from St. Petersburg, the ships proceeded 45 miles up the Neva River, through the Schlüsselburg Canal around Lake Lagoda and then to the mouth of the Sivr River and upriver to Lake Onega. The colonists then sailed out of Lake Onega into the Vytegra River and then down the Kovzha River to Beloye (White) Lake. At the time, there was likely a short overland portage at this point in the journey between the Vytegra River and the Kovzha River (the two rivers are now joined by a canal). The portage was accomplished by horse drawn wagon. Women, children and baggage were loaded aboard the wagons and the able bodied men walked.

At the southeast edge of White Lake they entered the Sheksna River which flows into the Volga River at Rybinsk.

Given that the Volga River freezes for most of its length for three months each year, it is likely that Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva spent their first winter and Christmas with Russian peasant families in or near Sheksna.

In the spring, when the river was again navigable, they continued down the remaining 1,000 meandering miles of the Volga to the frontier town of Saratov. The days on the river must have seemed endless as they drifted day after day. The trip down the Volga was difficult and large numbers of adults and children died along the way. The dead were taken to shore and quickly buried while relatives erected a improvised cross above it. Time was of the essence because they feared the groups of bandits hiding in the forests along the Volga.

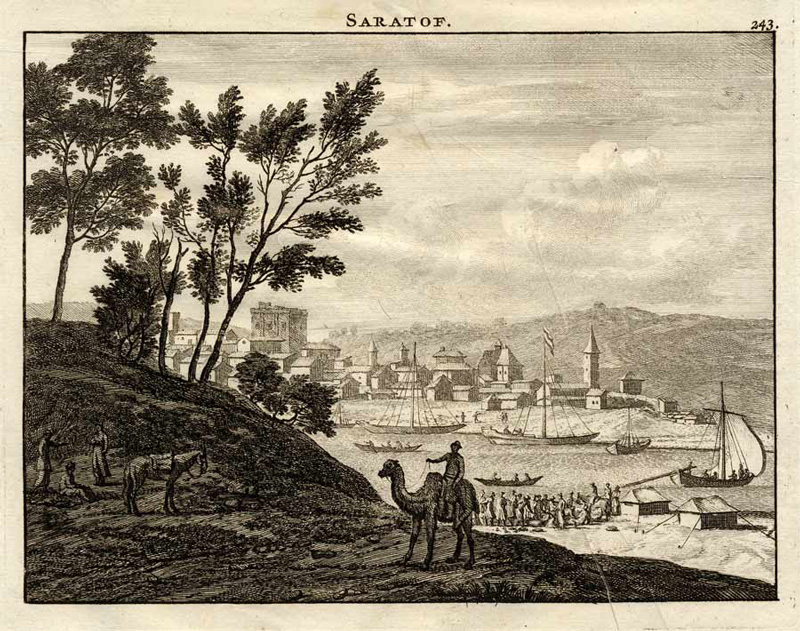

Sometime in early August, the transport group reached Saratov, the closest town to the colony of Norka. Saratov was established as a frontier fortress in 1590 by Tsar Feodor Ivanovich and would have been an unkempt, ramshackle town of about 10,000 residents in the 1760s. According to the 1767 census, Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva were provided with 25 rubles, one wagon, one saddle, two horses, one horse collar, one cow, some timber and other necessary items from the Guardianship Office established for the colonists in Saratov.

Sometime in early August, the transport group reached Saratov, the closest town to the colony of Norka. Saratov was established as a frontier fortress in 1590 by Tsar Feodor Ivanovich and would have been an unkempt, ramshackle town of about 10,000 residents in the 1760s. According to the 1767 census, Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva were provided with 25 rubles, one wagon, one saddle, two horses, one horse collar, one cow, some timber and other necessary items from the Guardianship Office established for the colonists in Saratov.

With their newly acquired horses and wagon, Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva began the final two day trek south from Saratov behind the military wagon master across the seemingly endless rolling steppe. Their eyes must have been straining to find the houses and farm buildings they were told were awaiting them.

After more than a year of travel from their homeland, the new colonists arrived at the banks of the Norka River on August 15, 1767. Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva were among this group that contained the majority of the first settlers in the colony of Norka.

In the remaining days of August and the month of September, more immigrant families continued to settle in Norka. Four more groups arrived on August 18th, August 26th, September 2nd and September 22nd. The Russian census list shows that there were 218 families comprised of 738 people living in the colony at the end of December 1767.

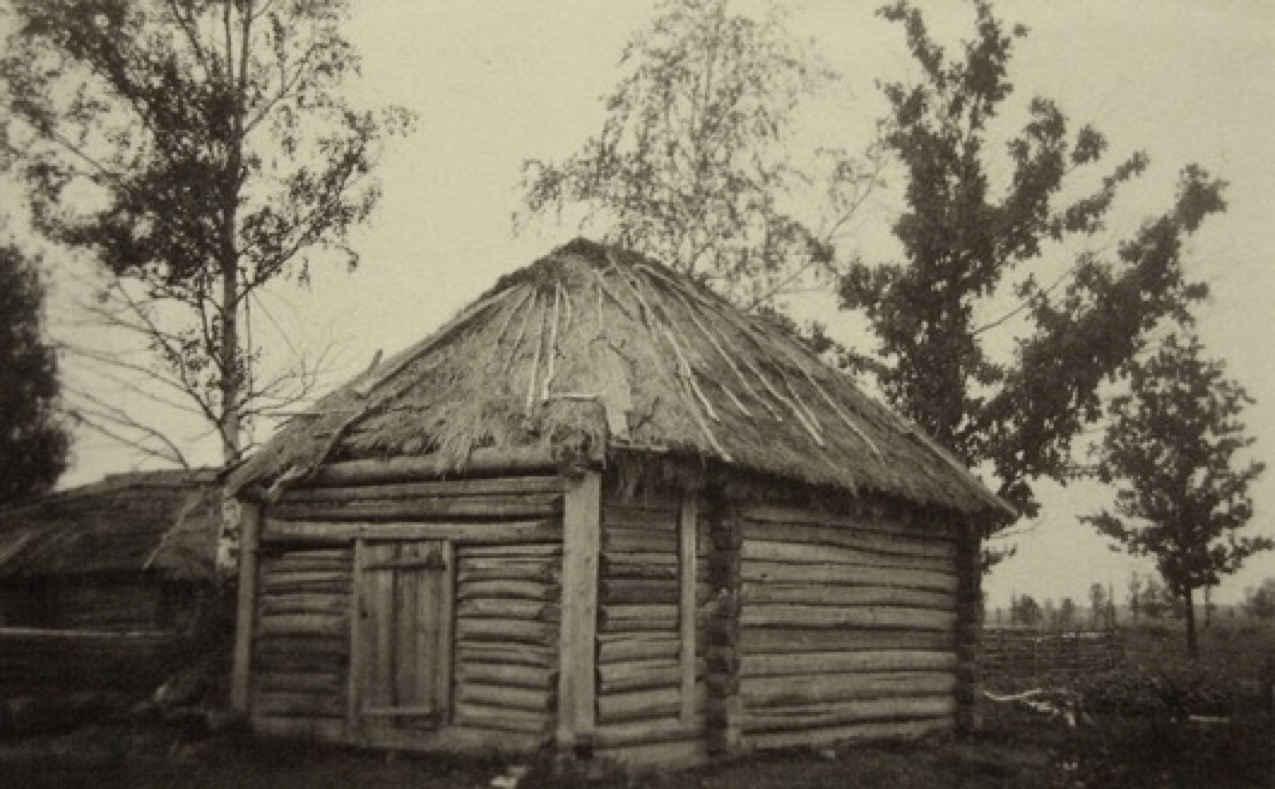

Because Norka was a Crown Colony (founded by the Russian government), a few log housed called Kron Häuser, or Crown Houses, had already been built when the colonists arrived. These houses were inadequate to shelter all the colonists and some had to build partially underground huts called Semlinka (Zemlyanky) in order to live through the first winters until more log housing could be built. The Semlinka were earth houses which consisted of excavated pits covered with a roof made of wagon planks, limbs, and twigs covered with a mixture of dry grass and mud. Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva spent their first Christmas together in Russia in one of these types of shelter.

In general, the preparations for the colonists were inadequate and they worked hard to prepare themselves for the oncoming winter months that would be much harsher than they experienced in Hessen.

One of the original Volga colonists, Anton Schneider, provided some insights into the early living conditions. He stated that "throughout the winter we lived miserably and in the greatest need. The dark winter days and the eternally long nights seemed to last forever. We were separate from all other human beings, and in many cases did not even have enough to eat."

Marauding packs of wolves were also reported to be a constant threat to the colonists and their livestock.

Stories passed down from the early settlers of Norka told of vicious dog-like animals who lived along the banks of the Norka river, that are twice the size of North American prairie gophers. These animals lived underground and legend has it that they sometimes attacked chickens, ducks and even small children. Local peasants called these animals "Norka", which in the Russian language is the name for the European mink.

What was it like for Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva that first Christmas in Norka? In December, the colony would have been blanketed in snow and ice. The Russian steppe was very different from the hilly and forested area in Hessen where Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva had been born and grown up. The rolling and wide open steppe near Norka had few coniferous trees that would have been common in Hessen. Perhaps the Schreiber's would have improvised, as some families did, by using a branch from a local tree which produced blossoms after being placed in a container of water in the house. The branch would then be decorated to resemble the familiar Christmas tree.

The colonists who had recently arrived in Norka were nearly all of the Reformed faith. It's likely that they gathered to give thanks for their new home and new opportunities in Russia. It's not difficult to imagine that they sang familiar Christmas songs and thought of their families and friends in far away Hessen even as they were making new friends in Norka. Songs familiar to us today like Stille Nacht (Silent Night) and O Tannenbaum (Oh Christmas Tree) had not yet been written in Germany. They may have sung traditional Christmas songs of the time like Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen (Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming) and Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her (From Heaven Above to Earth I Come) which were written in the 1500s and are known to be part of the music traditions of Unser Leit (Our People).

After more than a year of travel from their homeland, the new colonists arrived at the banks of the Norka River on August 15, 1767. Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva were among this group that contained the majority of the first settlers in the colony of Norka.

In the remaining days of August and the month of September, more immigrant families continued to settle in Norka. Four more groups arrived on August 18th, August 26th, September 2nd and September 22nd. The Russian census list shows that there were 218 families comprised of 738 people living in the colony at the end of December 1767.

Because Norka was a Crown Colony (founded by the Russian government), a few log housed called Kron Häuser, or Crown Houses, had already been built when the colonists arrived. These houses were inadequate to shelter all the colonists and some had to build partially underground huts called Semlinka (Zemlyanky) in order to live through the first winters until more log housing could be built. The Semlinka were earth houses which consisted of excavated pits covered with a roof made of wagon planks, limbs, and twigs covered with a mixture of dry grass and mud. Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva spent their first Christmas together in Russia in one of these types of shelter.

In general, the preparations for the colonists were inadequate and they worked hard to prepare themselves for the oncoming winter months that would be much harsher than they experienced in Hessen.

One of the original Volga colonists, Anton Schneider, provided some insights into the early living conditions. He stated that "throughout the winter we lived miserably and in the greatest need. The dark winter days and the eternally long nights seemed to last forever. We were separate from all other human beings, and in many cases did not even have enough to eat."

Marauding packs of wolves were also reported to be a constant threat to the colonists and their livestock.

Stories passed down from the early settlers of Norka told of vicious dog-like animals who lived along the banks of the Norka river, that are twice the size of North American prairie gophers. These animals lived underground and legend has it that they sometimes attacked chickens, ducks and even small children. Local peasants called these animals "Norka", which in the Russian language is the name for the European mink.

What was it like for Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva that first Christmas in Norka? In December, the colony would have been blanketed in snow and ice. The Russian steppe was very different from the hilly and forested area in Hessen where Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva had been born and grown up. The rolling and wide open steppe near Norka had few coniferous trees that would have been common in Hessen. Perhaps the Schreiber's would have improvised, as some families did, by using a branch from a local tree which produced blossoms after being placed in a container of water in the house. The branch would then be decorated to resemble the familiar Christmas tree.

The colonists who had recently arrived in Norka were nearly all of the Reformed faith. It's likely that they gathered to give thanks for their new home and new opportunities in Russia. It's not difficult to imagine that they sang familiar Christmas songs and thought of their families and friends in far away Hessen even as they were making new friends in Norka. Songs familiar to us today like Stille Nacht (Silent Night) and O Tannenbaum (Oh Christmas Tree) had not yet been written in Germany. They may have sung traditional Christmas songs of the time like Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen (Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming) and Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her (From Heaven Above to Earth I Come) which were written in the 1500s and are known to be part of the music traditions of Unser Leit (Our People).

Perhaps the Schreiber's joined the family of Johann Heinrich and Maria Elisabeth Döring to celebrate. The Döring's came from Isenburg (part of the modern day state of Hessen near Frankfurt) and were part of the same group of colonists that arrived in Norka with the Schreiber's on August 15th. Little did they know that their descendants would someday meet and marry in a far away place that would be known as Portland, Oregon - a place unknown to any European in 1767.

There was no church building or school house that first winter in Norka and the first pastor was not installed untll 1769. Given the isolated location of the colony, it is likely that lay people led the worship services until the church was formally established.

As part of the Christmas celebration in 1767, did the colonists find a young girl to dress up and act the part of the Christkind? It was customary for a young girl to be dressed in white, her face hidden by a veil and accompanied by a few boys and girls to go from house to house in search of all the good little children. She announced her arrival by appearing at the window and ringing a small bell. This greatly excited the children who were filled with the mixed emotion of joy and apprehension because she not only brought gifts and goodies, but also carried a switch for the youngsters who had been disobedient and naughty.

Did a young man dress up to play the traditional part of the Pelznickel? The Pelznickel, a sort of rough hewn Santa, dressed in a fur hat and coat, carried a ragged sack and rattled his chain while he looked for unruly children who did not respect or mind their parents.

Food provisions would have been limited in 1767, but perhaps there was enough to make the traditional Grebbel and Schnitzsuppe. I imagine that there must have been a bottle of vodka or schnapps available to make traditional Christmas toasts and to wash down the treats!

Surely, the Schreiber's would have read the story of the birth of Jesus from the book of Luke. We know that the traditions brought from Hessen were carried on in Norka and continue to be passed down to our children today.

Although we will never know exactly how Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva celebrated their first Christmas in Norka, I suspect that they were filled with a mixture of fear about the unknowns of their new homeland and excitement about the possibilities they could achieve through hard work on the Russian frontier. As they celebrated the birth of Jesus on December 25, 1767, did they already know that they would be blessed with their first child, Johann Heinrich, in the coming year?

Despite the very difficult situation for many of the Volga German colonists, Norka seems to have been an exceptional success story in the early years. Professor Peter Simon Pallas, who found so much grief in the other Volga colonies during his visit in 1773, points out the exceptional situation in the colonies of Norka and nearby Huck. Pallas wrote: "These colonies have since their founding produced their own grain not only for food, but for sale. They have procured for themselves all sorts of convenience and have even built their own granaries."

Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva were part of that success and were blessed with a total of five children in the years that followed that first Christmas in Norka. Each census list shows an expansion of their material wealth and a growing extended family.

Johann Wilhelm died sometime between the census taken in August 1811 and next census taken in 1834. Anna Eva died sometime between the census revisions of 1798 and 1811. Despite the hardships that Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva experienced, they had accomplished their dream of achieving greater freedom and economic success in Russia. Their story continues to serve as inspiration for hundreds of their descendants living around the world.

Let's think of Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva this Christmas and give thanks to their spirit and courage.

There was no church building or school house that first winter in Norka and the first pastor was not installed untll 1769. Given the isolated location of the colony, it is likely that lay people led the worship services until the church was formally established.

As part of the Christmas celebration in 1767, did the colonists find a young girl to dress up and act the part of the Christkind? It was customary for a young girl to be dressed in white, her face hidden by a veil and accompanied by a few boys and girls to go from house to house in search of all the good little children. She announced her arrival by appearing at the window and ringing a small bell. This greatly excited the children who were filled with the mixed emotion of joy and apprehension because she not only brought gifts and goodies, but also carried a switch for the youngsters who had been disobedient and naughty.

Did a young man dress up to play the traditional part of the Pelznickel? The Pelznickel, a sort of rough hewn Santa, dressed in a fur hat and coat, carried a ragged sack and rattled his chain while he looked for unruly children who did not respect or mind their parents.

Food provisions would have been limited in 1767, but perhaps there was enough to make the traditional Grebbel and Schnitzsuppe. I imagine that there must have been a bottle of vodka or schnapps available to make traditional Christmas toasts and to wash down the treats!

Surely, the Schreiber's would have read the story of the birth of Jesus from the book of Luke. We know that the traditions brought from Hessen were carried on in Norka and continue to be passed down to our children today.

Although we will never know exactly how Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva celebrated their first Christmas in Norka, I suspect that they were filled with a mixture of fear about the unknowns of their new homeland and excitement about the possibilities they could achieve through hard work on the Russian frontier. As they celebrated the birth of Jesus on December 25, 1767, did they already know that they would be blessed with their first child, Johann Heinrich, in the coming year?

Despite the very difficult situation for many of the Volga German colonists, Norka seems to have been an exceptional success story in the early years. Professor Peter Simon Pallas, who found so much grief in the other Volga colonies during his visit in 1773, points out the exceptional situation in the colonies of Norka and nearby Huck. Pallas wrote: "These colonies have since their founding produced their own grain not only for food, but for sale. They have procured for themselves all sorts of convenience and have even built their own granaries."

Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva were part of that success and were blessed with a total of five children in the years that followed that first Christmas in Norka. Each census list shows an expansion of their material wealth and a growing extended family.

Johann Wilhelm died sometime between the census taken in August 1811 and next census taken in 1834. Anna Eva died sometime between the census revisions of 1798 and 1811. Despite the hardships that Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva experienced, they had accomplished their dream of achieving greater freedom and economic success in Russia. Their story continues to serve as inspiration for hundreds of their descendants living around the world.

Let's think of Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva this Christmas and give thanks to their spirit and courage.

Source

Written by Steve Schreiber, Portland, Oregon, a descendant of Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva Schreiber, in December 2010 and updated in May 2017.

Last updated October 12, 2019.