Is My Name Schreiber or Becker?

While researching my Schreiber family, I ran into a brick wall that made me question a primary source of my identity, the family surname. I was confronted with the disconcerting possibility that my surname was Becker, not Schreiber. Could we have been using the wrong surname for over 245 years?

I started my genealogy work in the mid-1990s by gathering what I knew about my parents and grandparents. I then worked backward through each generation, documenting the relationships.

My father, Frederick Schreiber, was the son of Volga German immigrants from Norka, Russia. His parents were Gottfried Schreiber (born 1890) and Elizabeth Döring (born 1899). The first two generations in my Schreiber line were easy to document. Still, there was little information about my great-grandfather (only his name) and no information about anyone further back in the family lineage.

The timing for my research was fortunate. Up until the early 1990s, it was believed that all the church and civil records for the Volga Germans living in Russia had been destroyed when the entire population was deported to Siberia and Central Asia in 1941. Why would the Soviet government, under Joseph Stalin, keep documentation about an ethnic group they sought to eliminate?

With the advent of Perestroika and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1989, there were encouraging reports that records for the Volga German colonies had been preserved in the Russian archives located in the cities of Saratov, Engels, and Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad). Perhaps a window to the past was opening.

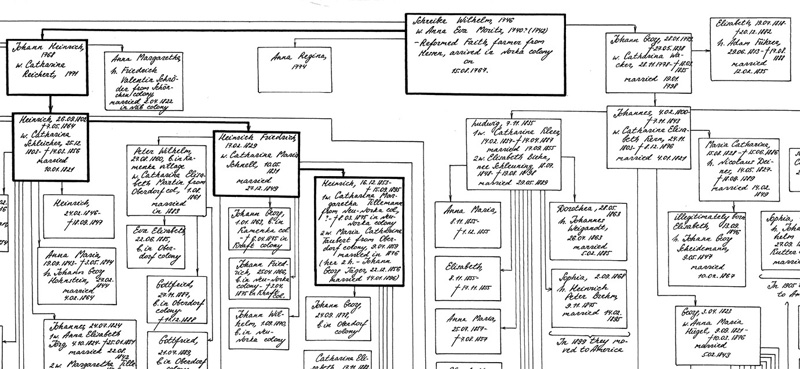

In 1997, I contacted Dr. Igor R. Pleve at Saratov State University in Saratov, Russia. Dr. Pleve is a historian who has published several books about the Volga Germans. Given his professional qualifications and residence in Saratov, Dr. Pleve had direct access to records in the Russian archives. I asked Dr. Pleve to prepare a descendants chart for me, starting with the first Schreiber family that settled in Norka, Russia, in 1767. I wanted to follow all of the descendants of that couple through my grandfather's generation. Dr. Pleve's research is based on supporting church and civil records for the Schreiber family held in the archives. I was very excited when the chart was completed in 1999, providing me with significant information on the Schreiber family. It is a real family treasure.

I learned from the descendants chart that my great-grandfather was Heinrich Schreiber (born 1853), and Heinrich's father was Heinrich Friedrich Schreiber (born 1829). Heinrich Friedrich's father was another Heinrich Schreiber (born 1802), the son of Johann Heinrich Schreiber (born 1768). Johann Heinrich was born just one year after his parents, Wilhelm Schreiber and Anna Eva Schreiber (née Moritz), arrived in Norka as part of the original group of colonists in August 1767.

I started my genealogy work in the mid-1990s by gathering what I knew about my parents and grandparents. I then worked backward through each generation, documenting the relationships.

My father, Frederick Schreiber, was the son of Volga German immigrants from Norka, Russia. His parents were Gottfried Schreiber (born 1890) and Elizabeth Döring (born 1899). The first two generations in my Schreiber line were easy to document. Still, there was little information about my great-grandfather (only his name) and no information about anyone further back in the family lineage.

The timing for my research was fortunate. Up until the early 1990s, it was believed that all the church and civil records for the Volga Germans living in Russia had been destroyed when the entire population was deported to Siberia and Central Asia in 1941. Why would the Soviet government, under Joseph Stalin, keep documentation about an ethnic group they sought to eliminate?

With the advent of Perestroika and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1989, there were encouraging reports that records for the Volga German colonies had been preserved in the Russian archives located in the cities of Saratov, Engels, and Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad). Perhaps a window to the past was opening.

In 1997, I contacted Dr. Igor R. Pleve at Saratov State University in Saratov, Russia. Dr. Pleve is a historian who has published several books about the Volga Germans. Given his professional qualifications and residence in Saratov, Dr. Pleve had direct access to records in the Russian archives. I asked Dr. Pleve to prepare a descendants chart for me, starting with the first Schreiber family that settled in Norka, Russia, in 1767. I wanted to follow all of the descendants of that couple through my grandfather's generation. Dr. Pleve's research is based on supporting church and civil records for the Schreiber family held in the archives. I was very excited when the chart was completed in 1999, providing me with significant information on the Schreiber family. It is a real family treasure.

I learned from the descendants chart that my great-grandfather was Heinrich Schreiber (born 1853), and Heinrich's father was Heinrich Friedrich Schreiber (born 1829). Heinrich Friedrich's father was another Heinrich Schreiber (born 1802), the son of Johann Heinrich Schreiber (born 1768). Johann Heinrich was born just one year after his parents, Wilhelm Schreiber and Anna Eva Schreiber (née Moritz), arrived in Norka as part of the original group of colonists in August 1767.

Satisfied that I had clear evidence of my family line back to the first settlers in Russia, I wanted to find out where Wilhelm and Anna Eva Schreiber had lived in Germany (then a collection of states, counties, independent cities, and principalities loosely organized under the Holy Roman Empire) before emigrating in 1766. I began this part of my research by collecting as much information about Wilhelm and Anna Eva as possible, hoping to discover a few clues about their origins.

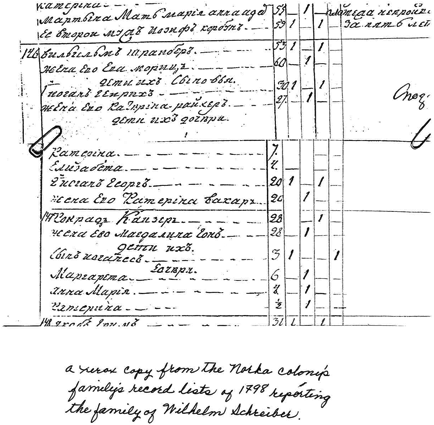

In the late 1990s, several census lists for Norka were acquired from the Russian archives and translated by the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia and private researchers. I read these records to find more information about Wilhelm and Anna Eva.

Neither Wilhelm nor Anna Eva Schreiber were listed in the 1834 census for Norka (translated and published by Brent Alan Mai in 2007). Both of them had been born in the mid-1700s and had likely died by the time this census was taken. Their son George and grandson Heinrich were listed separately (Household 124, p. 38 and Household 131, p. 40).

The 1811 census for Norka shows Wilhelm as the head of household 146, and he was 66 years old at that time (p. 30). The census also notes that Wilhelm's son, Heinrich, died in 1810, and Heinrich's son, also named Heinrich, is living with him. Wilhelm's other son, George (age 33), has moved in with the Ernst Eberling family (p. 22). The 1811 census determined land allotments in the colony based on the number of males in each household. As a result, information on females was missing, making it impossible to determine if Anna Eva was living at this time.

The 1798 and 1775 Russian census lists for the colony of Norka were translated by Rick Rye and published by The American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (AHSGR) in 1995. Brent Alan Mai also translated the 1798 census for all of the Volga German colonies in two volumes titled 1798 Census of the German Colonies along the Volga, published by AHSGR in 1999.

The 1798 census shows the following facts about Wilhelm and Anna Eva (AHSGR - p. 59 and Mai – p. 781):

Family 146 is Wilhelm Schreiber, age 53, and his wife Eva Moritz, age 60, with their sons:

Johann Heinrich Schreiber, age 30, and his wife Katarina Reicher(t), age 27.

Johann Georg Schreiber, age 20, and his wife Katarina Wacker, age 20.

Johann Heinrich Moritz, the father of Anna Eva and father-in-law of Wilhelm Schreiber, is listed in the 1775 census but not in the 1798 census. It is presumed that he died sometime between the 1775 and 1798 censuses.

Twenty-three years earlier, the 1775 Census shows the following information:

Household 139 (AHSGR - p. 22) is Wilhelm Schreiber, 27, and wife Anna Eva, 34, with their son, Johann Heinrich, 6 ½, and daughters Anna Katarina, 4, and Anna Regina, ¼. Wilhelm's father-in-law, Johann Heinrich Moritz, 69, is listed as part of this family household. Johann Heinrich Moritz's wife, who is listed in the 1767 census, is not listed in this census, and it is presumed that she died after the 1767 census.

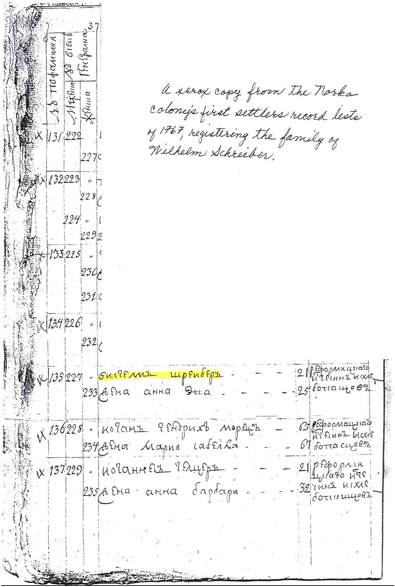

The first record of Wilhelm and Ana Eva in Norka is documented in the 1767 Russian Census (often referred to as the "First Settlers List"), which has been translated by Dr. Pleve and published in the book Einwanderung in das Wolgagebiet, 1764-1767, Band 3 (Emigration to the Volga region, 1764-1767, Volume 3).

The following information about Wilhelm and Anna Eva is included in the 1767 census:

Household 135 - Wilhelm Schreiber, 21, reformed faith, a farmer from Hessen, and his wife, Anna Eva, 25. They arrived in Norka colony on 15 August 1767. (p. 265). (Note: Schreiber is misspelled in the Pleve book as Schreiner. This error was acknowledged to me in an e-mail from Igor Pleve and will be corrected in new editions of the book.)

Household 136 - Johann Heinrich Moritz, 63, reformed faith, a farmer from Hessen, and his wife Maria Sibilla, 67. They arrived in Norka colony on 15 August 1767. (p. 265)

The 1767, 1775, 1798, and 1811 census documents all show Wilhelm's surname as Schreiber (see the exhibits for 1767 and 1798 below).

In the late 1990s, several census lists for Norka were acquired from the Russian archives and translated by the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia and private researchers. I read these records to find more information about Wilhelm and Anna Eva.

Neither Wilhelm nor Anna Eva Schreiber were listed in the 1834 census for Norka (translated and published by Brent Alan Mai in 2007). Both of them had been born in the mid-1700s and had likely died by the time this census was taken. Their son George and grandson Heinrich were listed separately (Household 124, p. 38 and Household 131, p. 40).

The 1811 census for Norka shows Wilhelm as the head of household 146, and he was 66 years old at that time (p. 30). The census also notes that Wilhelm's son, Heinrich, died in 1810, and Heinrich's son, also named Heinrich, is living with him. Wilhelm's other son, George (age 33), has moved in with the Ernst Eberling family (p. 22). The 1811 census determined land allotments in the colony based on the number of males in each household. As a result, information on females was missing, making it impossible to determine if Anna Eva was living at this time.

The 1798 and 1775 Russian census lists for the colony of Norka were translated by Rick Rye and published by The American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (AHSGR) in 1995. Brent Alan Mai also translated the 1798 census for all of the Volga German colonies in two volumes titled 1798 Census of the German Colonies along the Volga, published by AHSGR in 1999.

The 1798 census shows the following facts about Wilhelm and Anna Eva (AHSGR - p. 59 and Mai – p. 781):

Family 146 is Wilhelm Schreiber, age 53, and his wife Eva Moritz, age 60, with their sons:

Johann Heinrich Schreiber, age 30, and his wife Katarina Reicher(t), age 27.

Johann Georg Schreiber, age 20, and his wife Katarina Wacker, age 20.

Johann Heinrich Moritz, the father of Anna Eva and father-in-law of Wilhelm Schreiber, is listed in the 1775 census but not in the 1798 census. It is presumed that he died sometime between the 1775 and 1798 censuses.

Twenty-three years earlier, the 1775 Census shows the following information:

Household 139 (AHSGR - p. 22) is Wilhelm Schreiber, 27, and wife Anna Eva, 34, with their son, Johann Heinrich, 6 ½, and daughters Anna Katarina, 4, and Anna Regina, ¼. Wilhelm's father-in-law, Johann Heinrich Moritz, 69, is listed as part of this family household. Johann Heinrich Moritz's wife, who is listed in the 1767 census, is not listed in this census, and it is presumed that she died after the 1767 census.

The first record of Wilhelm and Ana Eva in Norka is documented in the 1767 Russian Census (often referred to as the "First Settlers List"), which has been translated by Dr. Pleve and published in the book Einwanderung in das Wolgagebiet, 1764-1767, Band 3 (Emigration to the Volga region, 1764-1767, Volume 3).

The following information about Wilhelm and Anna Eva is included in the 1767 census:

Household 135 - Wilhelm Schreiber, 21, reformed faith, a farmer from Hessen, and his wife, Anna Eva, 25. They arrived in Norka colony on 15 August 1767. (p. 265). (Note: Schreiber is misspelled in the Pleve book as Schreiner. This error was acknowledged to me in an e-mail from Igor Pleve and will be corrected in new editions of the book.)

Household 136 - Johann Heinrich Moritz, 63, reformed faith, a farmer from Hessen, and his wife Maria Sibilla, 67. They arrived in Norka colony on 15 August 1767. (p. 265)

The 1767, 1775, 1798, and 1811 census documents all show Wilhelm's surname as Schreiber (see the exhibits for 1767 and 1798 below).

When I began following Wilhelm and Anna Eva's paper trail further back in time, I encountered the brick wall and the question about my surname.

In 1766, after a long sea voyage, the new colonists arrived in Russia at Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov); the government ordered that records be made of each person arriving on each ship. Ivan Kuhlberg was given this responsibility, and the lists of the colonists that his clerks made were delivered to the Chancery of Oversight of Foreigners in nearby St. Petersburg. In 2010, the lists were translated and published in a book by Dr. Igor Pleve titled Lists of Colonists to Russia in 1766, Reports by Ivan Kuhlberg, and are known simply as the Kuhlberg Lists.

When I reviewed the lists, I expected to find Wilhelm Schreiber married to Anna Eva Schreiber (née Moritz). I was soon disappointed to discover that they were not listed. However, the lists did show a Johann Wilhelm Becker, of the Reformed faith, from Hessen (doc. No. 4991) accompanied by his wife Anna Eva (p. 317).

The family immediately preceding Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva Becker on the ship list is Johann Heinrich Mauritius (a French spelling of Moritz), a farmer from Hessen, and his wife Anna Maria (doc. No. 4990) (p. 317).

Both families arrived in Russia on August 9, 1766, sailing from the port of Lübeck in northern Germany as public colonists on the Russian galliot (or galiot) Strel 'Na under the command of Lieutenant Sornev.

It should be noted that Johann is a saint's name and would not be used for anything other than official records. Typically, Johann Wilhelm would only use the name Wilhelm in daily life.

From the 1767 and 1775 censuses, I knew that the Becker and Moritz families shown together in the Kuhlberg Lists were related and that Anna Eva was the daughter of Johann Heinrich Moritz. Further research showed that only one Moritz family (Johann Heinrich and Maria Moritz) was documented in the 1767 census for the Volga German colonies. This had to be Anna Eva, later shown in the census lists as married to Wilhelm Schreiber. The surprising yet unexplained fact was that she was married to Wilhelm Becker!

The mystery deepened when I found evidence of the marriage between Wilhelm Becker and Anna Eva Moritz in 1766, shortly before they emigrated from Germany.

The Russian government under Catherine II (the Great) preferred that their new colonists be married, and their recruiters provided financial incentives to encourage this. As a result, many marriages occurred in the cities where the recruiters gathered colonists and formed them into transport groups. One of these cities was Büdingen, located south of the Wetterau district below the Vogelsberg Mountains. The city is 15 kilometers northwest of Gelnhausen, and about 40 kilometers northeast of Frankfurt am Main. Many Volga German immigrants lived near Büdingen, part of the County of Isenburg.

Fortunately, the colonist marriage registers for the Lutheran Church (Evangelische Kirche) in Büdingen have survived (LDS International Film Number 1197023), and four translations have been published.

The first translation of the marriage lists was printed in an article by Hermann Hoffmann titled Auswanderungen nach Rußland im Jahre 1766, Mitteilungen der Hessischen Familiengeschichtlichen Vereinigung zu Darmstadt, Issue 4 (January 1927), pp. 109-122. Many of these marriages were also extracted by Dr. Karl Stumpp and printed in the book The Emigration from Germany to Russia in the Years 1763-1862 (pp. 117-165). The third translation of the marriage lists was published in the book German Migration to the Russian Volga 1764-1767 (pp. 44-101) by Brent Alan Mai and Dona Reeves-Marquardt. A fourth translation of the lists was prepared by Dr. Klaus-Peter Decker in his book titled Büdingen als Sammelplatz der Auswanderung an die Wolga 1766 (Büdingen as a gathering place for emigration to the Volga in 1766), p. 72.

I hoped that the marriage lists would provide a clear path to where Wilhelm and Anna Eva were living before their marriage. Unfortunately, there were differences between the three Büdingen marriage register translations that provided new clues but no clear path.

Dr. Stumpp indicates that Wilhelm Becker was from Ronhausen near Marburg in Hessen and Eva Moritz from Reckershausen/Hünsruck (p. 120). Hoffmann's translation lists her name as A. Eva Moritz.

According to the translation by Mai and Reeves-Marquardt, Wilhelm Becker was from Ronshausen in the district of Rothenburg (also Rotenburg), and he married Anna Eva Moritz from Sterckels on May 7, 1766, in Büdingen (p. 82 – couple #620). The translation by Dr. Decker is consistent with that of Mai and Reeves-Marquardt.

It is important to note that Ronshausen in the Hersfeld-Rotenburg district is a different geographic location than Ronhausen in the district of Marburg. The similarity in the names and the fact that the two small villages are nearby (about 50 miles apart) may explain the differences between sources.

The documentation I had collected confronted me with the question of whether or not Wilhelm Becker and Wilhelm Schreiber were the same person.

I explored four possible explanations of the Becker-Schreiber mystery. After several years of research, I concluded that only one explanation was supported by facts.

The first explanation I explored was that Anna Eva had two husbands and that her first husband, Wilhelm Becker, died during the nearly one-year journey from Oranienbaum (where he was recorded on the Kuhlberg Lists) to Norka. Under this scenario, I presumed that Anna Eva married Wilhelm Schreiber before the 1767 census. Although deaths were common on the arduous journey to the lower Volga, the documents from that period do not support this explanation. A detailed review of the Kuhlberg Lists shows that only one colonist named Johann Wilhelm Schreiber immigrated to Russia in 1766. This person is listed as single and a candidate of theology (Einwanderung p. 183). This Johann Wilhelm Schreiber is also listed in a book by Erik Amburger titled Die Pastoren der evangelischen Kirchen Rußlands (Pastors of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Russia) and is said to be from Mecklenburg. This Johann Wilhelm Schreiber served the colony of Belovez in Cernigov from 1767 to 1802 (the Belowesch colonies in Chernigov were then part of Russia and are now part of Russia and Ukraine). Given his theological profession and residence in another part of Russia, this Johann Wilhelm Schreiber could not have married Anna Eva Becker (née Moritz) and been documented as living in Norka for many years. In addition, the 1767 generally indicates if a woman had been a widow and later remarried. There is no such indication that Anna Eva Schreiber was a widow.

A second possible explanation is that clerks simply recorded Wilhelm Schreiber's name incorrectly as Becker. This theory is unlikely, given that the surname Becker was recorded on both the Büdingen marriage register and the Kuhlberg lists. These records were made by different clerks in two different parts of Europe. Phonetically, the two surnames also sound very different. Undoubtedly, the name Becker was not written down twice by mistake.

A third possibility is that Wilhelm was born with the surname Becker and chose to change his name to Schreiber when he arrived in Russia. This explanation was explored with the help of Dr. Gerd W. Jungblut, a genealogist in Germany. In 2002, I asked Dr. Jungblut to search for Wilhelm Becker's name in the church records for Ronshausen. Dr. Jungblut did not find anyone named Wilhelm Becker in the Ronshausen records over a 40-year period (1720-1760) around Wilhelm's estimated birth in 1745. I also searched for a Wilhelm Becker in the Ronhausen (Marburg) church records during this period and found no one with that name who was the right age. This possibility also seems unlikely because if Wilhelm wanted to change his name in Russia, he would have likely made this change in Oranienbaum rather than waiting until he settled in Norka. Once in Norka, there would be no apparent reason to change his birth name from Becker to Schreiber.

A fourth possible explanation is that Wilhelm purposely changed his name from Schreiber to Becker (a common German name) because he did not have the necessary permissions to leave home, marry, and emigrate to a foreign land. He may have been trying to avoid detection until he had safely arrived at the settlement point in Russia, where he would be far from the authorities that could send him back.

To prove or disprove this theory, I had to find a Johann Wilhelm Schreiber, born between 1745 and 1750 in either Ronhausen or Ronshausen.

I contacted the archives in Germany that hold the church registers for Ronhausen and Ronshausen, and they both told me that there were no Johann Wilhelm Schreibers listed in the records for a broad range of years around 1745. I was disappointed that all my possible explanations had come to a brick wall.

I continued to believe that the most likely explanation was that Johann Wilhelm temporarily changed his name from Schreiber to Becker. By chance, in March 2012, I entered "Johann Wilhelm Schreiber Ronshausen" into the Google search engine, not expecting to find relevant information about someone born over 260 years ago. To my amazement, I found a link to a post on Ancestry.com.au (Australia) that mentioned a record of a Johann Wilhelm Schreiber in the Ronshausen church register. The message said this information had been obtained from Heinrich Tann, the Ronshausen church bookkeeper and a genealogist. I sent an e-mail to the person who posted the message on Ancestry.com.au, and he provided me with Heinrich Tann's address in Germany. I wrote and mailed a letter to Mr. Tann, hoping he would answer my questions.

In 1766, after a long sea voyage, the new colonists arrived in Russia at Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov); the government ordered that records be made of each person arriving on each ship. Ivan Kuhlberg was given this responsibility, and the lists of the colonists that his clerks made were delivered to the Chancery of Oversight of Foreigners in nearby St. Petersburg. In 2010, the lists were translated and published in a book by Dr. Igor Pleve titled Lists of Colonists to Russia in 1766, Reports by Ivan Kuhlberg, and are known simply as the Kuhlberg Lists.

When I reviewed the lists, I expected to find Wilhelm Schreiber married to Anna Eva Schreiber (née Moritz). I was soon disappointed to discover that they were not listed. However, the lists did show a Johann Wilhelm Becker, of the Reformed faith, from Hessen (doc. No. 4991) accompanied by his wife Anna Eva (p. 317).

The family immediately preceding Johann Wilhelm and Anna Eva Becker on the ship list is Johann Heinrich Mauritius (a French spelling of Moritz), a farmer from Hessen, and his wife Anna Maria (doc. No. 4990) (p. 317).

Both families arrived in Russia on August 9, 1766, sailing from the port of Lübeck in northern Germany as public colonists on the Russian galliot (or galiot) Strel 'Na under the command of Lieutenant Sornev.

It should be noted that Johann is a saint's name and would not be used for anything other than official records. Typically, Johann Wilhelm would only use the name Wilhelm in daily life.

From the 1767 and 1775 censuses, I knew that the Becker and Moritz families shown together in the Kuhlberg Lists were related and that Anna Eva was the daughter of Johann Heinrich Moritz. Further research showed that only one Moritz family (Johann Heinrich and Maria Moritz) was documented in the 1767 census for the Volga German colonies. This had to be Anna Eva, later shown in the census lists as married to Wilhelm Schreiber. The surprising yet unexplained fact was that she was married to Wilhelm Becker!

The mystery deepened when I found evidence of the marriage between Wilhelm Becker and Anna Eva Moritz in 1766, shortly before they emigrated from Germany.

The Russian government under Catherine II (the Great) preferred that their new colonists be married, and their recruiters provided financial incentives to encourage this. As a result, many marriages occurred in the cities where the recruiters gathered colonists and formed them into transport groups. One of these cities was Büdingen, located south of the Wetterau district below the Vogelsberg Mountains. The city is 15 kilometers northwest of Gelnhausen, and about 40 kilometers northeast of Frankfurt am Main. Many Volga German immigrants lived near Büdingen, part of the County of Isenburg.

Fortunately, the colonist marriage registers for the Lutheran Church (Evangelische Kirche) in Büdingen have survived (LDS International Film Number 1197023), and four translations have been published.

The first translation of the marriage lists was printed in an article by Hermann Hoffmann titled Auswanderungen nach Rußland im Jahre 1766, Mitteilungen der Hessischen Familiengeschichtlichen Vereinigung zu Darmstadt, Issue 4 (January 1927), pp. 109-122. Many of these marriages were also extracted by Dr. Karl Stumpp and printed in the book The Emigration from Germany to Russia in the Years 1763-1862 (pp. 117-165). The third translation of the marriage lists was published in the book German Migration to the Russian Volga 1764-1767 (pp. 44-101) by Brent Alan Mai and Dona Reeves-Marquardt. A fourth translation of the lists was prepared by Dr. Klaus-Peter Decker in his book titled Büdingen als Sammelplatz der Auswanderung an die Wolga 1766 (Büdingen as a gathering place for emigration to the Volga in 1766), p. 72.

I hoped that the marriage lists would provide a clear path to where Wilhelm and Anna Eva were living before their marriage. Unfortunately, there were differences between the three Büdingen marriage register translations that provided new clues but no clear path.

Dr. Stumpp indicates that Wilhelm Becker was from Ronhausen near Marburg in Hessen and Eva Moritz from Reckershausen/Hünsruck (p. 120). Hoffmann's translation lists her name as A. Eva Moritz.

According to the translation by Mai and Reeves-Marquardt, Wilhelm Becker was from Ronshausen in the district of Rothenburg (also Rotenburg), and he married Anna Eva Moritz from Sterckels on May 7, 1766, in Büdingen (p. 82 – couple #620). The translation by Dr. Decker is consistent with that of Mai and Reeves-Marquardt.

It is important to note that Ronshausen in the Hersfeld-Rotenburg district is a different geographic location than Ronhausen in the district of Marburg. The similarity in the names and the fact that the two small villages are nearby (about 50 miles apart) may explain the differences between sources.

The documentation I had collected confronted me with the question of whether or not Wilhelm Becker and Wilhelm Schreiber were the same person.

I explored four possible explanations of the Becker-Schreiber mystery. After several years of research, I concluded that only one explanation was supported by facts.

The first explanation I explored was that Anna Eva had two husbands and that her first husband, Wilhelm Becker, died during the nearly one-year journey from Oranienbaum (where he was recorded on the Kuhlberg Lists) to Norka. Under this scenario, I presumed that Anna Eva married Wilhelm Schreiber before the 1767 census. Although deaths were common on the arduous journey to the lower Volga, the documents from that period do not support this explanation. A detailed review of the Kuhlberg Lists shows that only one colonist named Johann Wilhelm Schreiber immigrated to Russia in 1766. This person is listed as single and a candidate of theology (Einwanderung p. 183). This Johann Wilhelm Schreiber is also listed in a book by Erik Amburger titled Die Pastoren der evangelischen Kirchen Rußlands (Pastors of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Russia) and is said to be from Mecklenburg. This Johann Wilhelm Schreiber served the colony of Belovez in Cernigov from 1767 to 1802 (the Belowesch colonies in Chernigov were then part of Russia and are now part of Russia and Ukraine). Given his theological profession and residence in another part of Russia, this Johann Wilhelm Schreiber could not have married Anna Eva Becker (née Moritz) and been documented as living in Norka for many years. In addition, the 1767 generally indicates if a woman had been a widow and later remarried. There is no such indication that Anna Eva Schreiber was a widow.

A second possible explanation is that clerks simply recorded Wilhelm Schreiber's name incorrectly as Becker. This theory is unlikely, given that the surname Becker was recorded on both the Büdingen marriage register and the Kuhlberg lists. These records were made by different clerks in two different parts of Europe. Phonetically, the two surnames also sound very different. Undoubtedly, the name Becker was not written down twice by mistake.

A third possibility is that Wilhelm was born with the surname Becker and chose to change his name to Schreiber when he arrived in Russia. This explanation was explored with the help of Dr. Gerd W. Jungblut, a genealogist in Germany. In 2002, I asked Dr. Jungblut to search for Wilhelm Becker's name in the church records for Ronshausen. Dr. Jungblut did not find anyone named Wilhelm Becker in the Ronshausen records over a 40-year period (1720-1760) around Wilhelm's estimated birth in 1745. I also searched for a Wilhelm Becker in the Ronhausen (Marburg) church records during this period and found no one with that name who was the right age. This possibility also seems unlikely because if Wilhelm wanted to change his name in Russia, he would have likely made this change in Oranienbaum rather than waiting until he settled in Norka. Once in Norka, there would be no apparent reason to change his birth name from Becker to Schreiber.

A fourth possible explanation is that Wilhelm purposely changed his name from Schreiber to Becker (a common German name) because he did not have the necessary permissions to leave home, marry, and emigrate to a foreign land. He may have been trying to avoid detection until he had safely arrived at the settlement point in Russia, where he would be far from the authorities that could send him back.

To prove or disprove this theory, I had to find a Johann Wilhelm Schreiber, born between 1745 and 1750 in either Ronhausen or Ronshausen.

I contacted the archives in Germany that hold the church registers for Ronhausen and Ronshausen, and they both told me that there were no Johann Wilhelm Schreibers listed in the records for a broad range of years around 1745. I was disappointed that all my possible explanations had come to a brick wall.

I continued to believe that the most likely explanation was that Johann Wilhelm temporarily changed his name from Schreiber to Becker. By chance, in March 2012, I entered "Johann Wilhelm Schreiber Ronshausen" into the Google search engine, not expecting to find relevant information about someone born over 260 years ago. To my amazement, I found a link to a post on Ancestry.com.au (Australia) that mentioned a record of a Johann Wilhelm Schreiber in the Ronshausen church register. The message said this information had been obtained from Heinrich Tann, the Ronshausen church bookkeeper and a genealogist. I sent an e-mail to the person who posted the message on Ancestry.com.au, and he provided me with Heinrich Tann's address in Germany. I wrote and mailed a letter to Mr. Tann, hoping he would answer my questions.

In the meantime, I searched the web and found a site for Ronshausen. The site listed the contact name and e-mail address for the Pfarrer (Pastor) of the church, Rev. Thomas Nickel. I contacted Rev. Nickel by e-mail, told him about my research, and mentioned that I was planning a family vacation to Germany in the summer of 2012. Rev. Nickel invited me to see the church records for myself and tempted me with the comment, "You will be interested to see what is written in the records about Johann Wilhelm Schreiber."

Shortly after, I received a handwritten letter from Heinrich Tann, who also encouraged me to visit Ronshausen. Heinrich (age 90) confirmed that he had served for many years as the record keeper for the Ronshausen church and was also an experienced genealogist.

My family and I arrived in Ronshausen on the morning of July 3, 2012, the date I had agreed to meet Rev. Nickel and Heinrich Tann. I expected a short visit to examine the church register, hoping that it would confirm my theory that Wilhelm Schreiber was, in fact, my direct ancestor. What happened next was utterly unexpected.

Not only were Rev. Nickel and Heinrich Tann there to greet us, but also the Bürgermeister (Mayor) of Ronshausen, Markus Becker, who provided a warm welcome and presented us with several wonderful books on the history of Ronshausen.

There was also a group of descendants of the Schreiber family from Ronshausen that live in the village today. With them was another Schreiber family that had emigrated from Russia to Germany in recent years. The family branch from Russia had also tracked the origins of the Schreiber family to Ronshausen and visited the church several years earlier. When they heard from Rev. Nickel and Heinrich Tann that we were coming to Ronshausen, they took the train from their home near Köln (Cologne) to meet us.

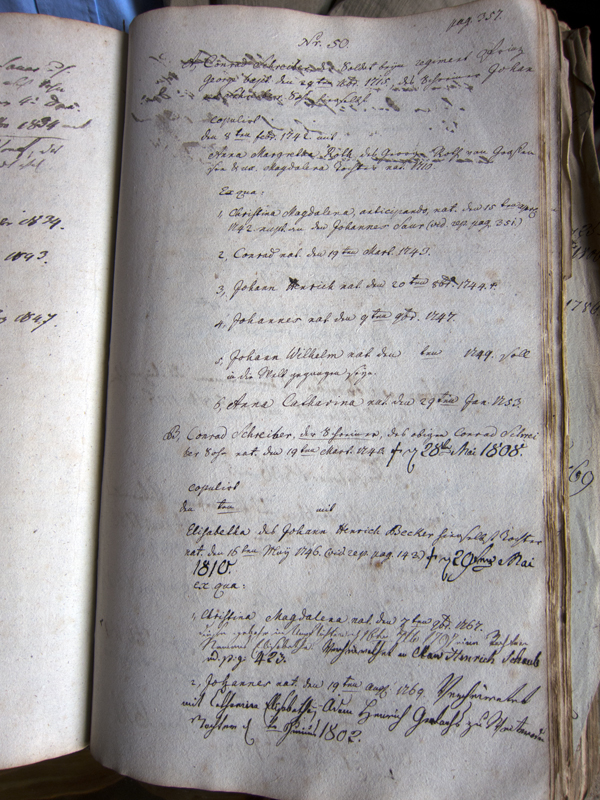

We gathered in the church courtyard, introduced ourselves in a mixture of German and English, and posed for several group photos. Rev. Nickel then invited us into the church to look at the original register showing the family of Johann Wilhelm Schreiber.

Johann Wilhelm's father was Conrad Schreiber, a Musketeer in the Prinz Georg Regiment, and his mother was Anna Margaretha (née Roth) from Marksuhl in Thüringia (about 15 miles from Ronshausen). During that period, Friedrich II, landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, was building his Hessian Army so he could lease them to his Uncle, King George III of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, to send to the American Colonies to fight the 'rebels.' I later learned that in the Thirty Years' War from 1618 to 1648 and the Seven Years' War from 1756 to 1763, Ronshausen had been abandoned several times due to the fighting in this area. In 1757, all of the inhabitants of Ronshausen fled into the woods as French troops occupied the village. Johann Wilhelm, along with his family, would have experienced this traumatic event.

Given his personal experience and that of his father, the opportunity to escape warfare was likely a significant factor in why Wilhelm changed his name and emigrated from Hessen. Since Wilhelm was young and single, he may have intended to avoid compulsory military service. It is possible Wilhelm discussed the matter with his father and decided that it was better to pursue a new life as a colonist in Russia than to fight and die in someone else's war. During the 1770s and 1780s, at least 64 young men from Ronshausen were conscripted to serve in the Hessian army that was hired to fight for the British in North America. This was a significant sacrifice for a small village of less than 500 people (population 468 in 1780). Most of these young men were about the same age as Johann Wilhelm.

The church register showed that Johann Wilhelm Schreiber was baptized on Heiligabend (Christmas Eve) on December 24, 1749. Typically, in this region of Germany, infants were baptized within a few days after their birth. The church register proved that a Johann Wilhelm Schreiber was born in Ronshausen in the right time frame.

The church register also showed that Johann Wilhelm was confirmed in Ronshausen in 1763 at the age of 14. His confirmation occurred just after the signing of the Treaty of Hubertusburg in February 1763, which ended the Seven Year's War.

The final entry for Johann Wilhelm was the key evidence I sought. The entry read: Soll in die Welt gegangen Sein. This phrase meant that Johann Wilhelm "went out into the world" sometime after his confirmation - probably in late 1765 or early 1766. Heinrich Tann told me that this note meant that Johann Wilhelm went to "a foreign land" - not just another village in the region. As further evidence, Herr Tann told me there was no indication in the church records that Wilhelm ever returned to Ronshausen.

Shortly after, I received a handwritten letter from Heinrich Tann, who also encouraged me to visit Ronshausen. Heinrich (age 90) confirmed that he had served for many years as the record keeper for the Ronshausen church and was also an experienced genealogist.

My family and I arrived in Ronshausen on the morning of July 3, 2012, the date I had agreed to meet Rev. Nickel and Heinrich Tann. I expected a short visit to examine the church register, hoping that it would confirm my theory that Wilhelm Schreiber was, in fact, my direct ancestor. What happened next was utterly unexpected.

Not only were Rev. Nickel and Heinrich Tann there to greet us, but also the Bürgermeister (Mayor) of Ronshausen, Markus Becker, who provided a warm welcome and presented us with several wonderful books on the history of Ronshausen.

There was also a group of descendants of the Schreiber family from Ronshausen that live in the village today. With them was another Schreiber family that had emigrated from Russia to Germany in recent years. The family branch from Russia had also tracked the origins of the Schreiber family to Ronshausen and visited the church several years earlier. When they heard from Rev. Nickel and Heinrich Tann that we were coming to Ronshausen, they took the train from their home near Köln (Cologne) to meet us.

We gathered in the church courtyard, introduced ourselves in a mixture of German and English, and posed for several group photos. Rev. Nickel then invited us into the church to look at the original register showing the family of Johann Wilhelm Schreiber.

Johann Wilhelm's father was Conrad Schreiber, a Musketeer in the Prinz Georg Regiment, and his mother was Anna Margaretha (née Roth) from Marksuhl in Thüringia (about 15 miles from Ronshausen). During that period, Friedrich II, landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, was building his Hessian Army so he could lease them to his Uncle, King George III of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, to send to the American Colonies to fight the 'rebels.' I later learned that in the Thirty Years' War from 1618 to 1648 and the Seven Years' War from 1756 to 1763, Ronshausen had been abandoned several times due to the fighting in this area. In 1757, all of the inhabitants of Ronshausen fled into the woods as French troops occupied the village. Johann Wilhelm, along with his family, would have experienced this traumatic event.

Given his personal experience and that of his father, the opportunity to escape warfare was likely a significant factor in why Wilhelm changed his name and emigrated from Hessen. Since Wilhelm was young and single, he may have intended to avoid compulsory military service. It is possible Wilhelm discussed the matter with his father and decided that it was better to pursue a new life as a colonist in Russia than to fight and die in someone else's war. During the 1770s and 1780s, at least 64 young men from Ronshausen were conscripted to serve in the Hessian army that was hired to fight for the British in North America. This was a significant sacrifice for a small village of less than 500 people (population 468 in 1780). Most of these young men were about the same age as Johann Wilhelm.

The church register showed that Johann Wilhelm Schreiber was baptized on Heiligabend (Christmas Eve) on December 24, 1749. Typically, in this region of Germany, infants were baptized within a few days after their birth. The church register proved that a Johann Wilhelm Schreiber was born in Ronshausen in the right time frame.

The church register also showed that Johann Wilhelm was confirmed in Ronshausen in 1763 at the age of 14. His confirmation occurred just after the signing of the Treaty of Hubertusburg in February 1763, which ended the Seven Year's War.

The final entry for Johann Wilhelm was the key evidence I sought. The entry read: Soll in die Welt gegangen Sein. This phrase meant that Johann Wilhelm "went out into the world" sometime after his confirmation - probably in late 1765 or early 1766. Heinrich Tann told me that this note meant that Johann Wilhelm went to "a foreign land" - not just another village in the region. As further evidence, Herr Tann told me there was no indication in the church records that Wilhelm ever returned to Ronshausen.

Wilhelm was only 16 years old when he left Ronshausen. Heinrich Tann told me that a young man had to be 18 years old to obtain permission to leave the village or to marry during this period. Fearing that his real identity and age would be discovered, Wilhelm likely signed an agreement with the Russian recruiters using the pseudonym Becker. He again used the name Becker when he married Anna Eva Moritz in Büdingen. Having been documented twice as Becker, Wilhelm would have had to continue using this surname when he boarded the ship bound for Russia and again when they disembarked in Oranienbaum. The Russian officials likely compared the names of those boarding at the departure ports and those who arrived at the immigration control point.

Why did Wilhelm choose the alias of Becker? One of Wilhelm's brothers was married to a Becker. More importantly, two older men from Ronshausen, Anton (age 59) and Johann Georg (age 39) Becker, also migrated to Russia and settled in Norka. Anton Becker was a widower and also married in Büdingen. Georg Becker was the son of Anton and was married with at least two children at the time of emigration to Russia. Two of Anton Becker's daughters were married to two brothers, Johannes and Johann Georg Eisel (Eÿsel), who were from nearby Friedewald. These couples were part of the small Ronhausen contingent that migrated to Russia and settled in the colony of Norka.

Wilhelm almost certainly departed from Ronshausen around April 1766 with the Beckers and related family members. Wilhelm likely claimed to be the son of one of the Becker men, probably Georg, whose two children were of similar age to be siblings. Given that Wilhelm was a minor, he needed his surrogate father's permission to be married in Büdingen and to sign an agreement with the Russian recruiters.

After a year of travel to the lower Volga and their arrival in Norka on August 15, 1767, Wilhelm would have felt safe reverting to his actual surname, Schreiber. By then, it was improbable he would be sent home given the great distance, the cost, and the fact that no one would benefit. When the Russian census takers came during the first year of settlement and asked his name, Wilhelm probably felt relieved to stop using his pseudonym and gladly gave his actual family name.

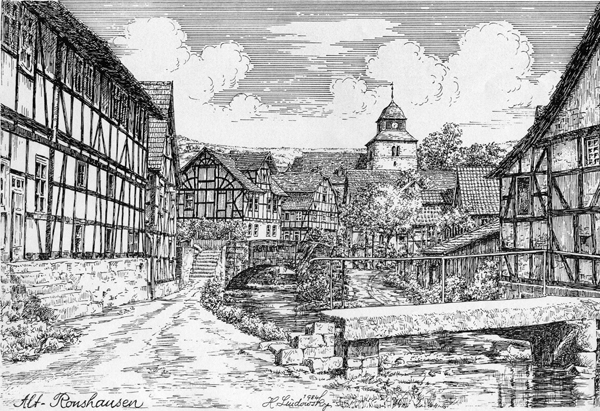

I was attempting to process this flood of information when Rev. Nickel invited me to stand at the place in the church where Johann Wilhelm Schreiber was baptized in 1749. It was a magic moment to stand where my 5th great-grandfather and his parents had stood 245 years earlier.

The Ronshausen church dates back to 1240 when the square church tower was constructed. The interior was beautifully painted in the Baroque style in the early 1700s and has changed little since Johann Wilhelm was a boy. We were informed that the church is considered one of the 100 most beautiful in Germany.

Why did Wilhelm choose the alias of Becker? One of Wilhelm's brothers was married to a Becker. More importantly, two older men from Ronshausen, Anton (age 59) and Johann Georg (age 39) Becker, also migrated to Russia and settled in Norka. Anton Becker was a widower and also married in Büdingen. Georg Becker was the son of Anton and was married with at least two children at the time of emigration to Russia. Two of Anton Becker's daughters were married to two brothers, Johannes and Johann Georg Eisel (Eÿsel), who were from nearby Friedewald. These couples were part of the small Ronhausen contingent that migrated to Russia and settled in the colony of Norka.

Wilhelm almost certainly departed from Ronshausen around April 1766 with the Beckers and related family members. Wilhelm likely claimed to be the son of one of the Becker men, probably Georg, whose two children were of similar age to be siblings. Given that Wilhelm was a minor, he needed his surrogate father's permission to be married in Büdingen and to sign an agreement with the Russian recruiters.

After a year of travel to the lower Volga and their arrival in Norka on August 15, 1767, Wilhelm would have felt safe reverting to his actual surname, Schreiber. By then, it was improbable he would be sent home given the great distance, the cost, and the fact that no one would benefit. When the Russian census takers came during the first year of settlement and asked his name, Wilhelm probably felt relieved to stop using his pseudonym and gladly gave his actual family name.

I was attempting to process this flood of information when Rev. Nickel invited me to stand at the place in the church where Johann Wilhelm Schreiber was baptized in 1749. It was a magic moment to stand where my 5th great-grandfather and his parents had stood 245 years earlier.

The Ronshausen church dates back to 1240 when the square church tower was constructed. The interior was beautifully painted in the Baroque style in the early 1700s and has changed little since Johann Wilhelm was a boy. We were informed that the church is considered one of the 100 most beautiful in Germany.

Heinrich Tann presented me with a complete genealogy of the Schreiber family from Ronshausen. This was a unique and unexpected gift. Heinrich told us that he was a personal friend and schoolmate of the last person with the Schreiber surname living in the village.

The Schreiber family arrived in Ronshausen in the mid-1600s when Jakob Schreiber established a Schneidmuhle (a water-powered sawmill). Most of the descendants of Jakob Schreiber were master carpenters. Perhaps this family skill was passed down through the generations. My grandfather, Gottfried Schreiber, was a master carpenter for the Union Pacific Railroad and practiced his craft on their business club cars.

After leaving the church, we were escorted to the site of the former Schreiber sawmill that still exists today. The mill was sold to the Fend family on February 24, 1841, and they continue to operate it. The house where Johann Wilhelm had lived with his parents was torn down in 1948, but I was presented with an old photo of the home and mill. In my wildest dreams, I did not expect to see the place where Wilhelm Schreiber and his family had lived.

The Schreiber family arrived in Ronshausen in the mid-1600s when Jakob Schreiber established a Schneidmuhle (a water-powered sawmill). Most of the descendants of Jakob Schreiber were master carpenters. Perhaps this family skill was passed down through the generations. My grandfather, Gottfried Schreiber, was a master carpenter for the Union Pacific Railroad and practiced his craft on their business club cars.

After leaving the church, we were escorted to the site of the former Schreiber sawmill that still exists today. The mill was sold to the Fend family on February 24, 1841, and they continue to operate it. The house where Johann Wilhelm had lived with his parents was torn down in 1948, but I was presented with an old photo of the home and mill. In my wildest dreams, I did not expect to see the place where Wilhelm Schreiber and his family had lived.

We then were taken to the home of Karl Röhn, a 4th cousin, who provided the entire group with a delicious meal. We looked through old family photos while we ate.

My head was pounding from all the information I'd been presented with and the excitement that came with the knowledge that I'd found the place of my Schreiber ancestor's origin in Germany. It had truly been an unforgettable day!

Before leaving Ronshausen, we drove through the hills above the town for the panoramic view. Another surprise awaited us when we found a beautiful overlook with a sign that said Stephan's Ruh (Steven's Rest). After the long search for Johann Wilhelm Schreiber, I felt like I had earned a short respite, gazing out at the place he once called home.

After many years of uncertainty, it's good to know that I am indeed a Schreiber after all.

My head was pounding from all the information I'd been presented with and the excitement that came with the knowledge that I'd found the place of my Schreiber ancestor's origin in Germany. It had truly been an unforgettable day!

Before leaving Ronshausen, we drove through the hills above the town for the panoramic view. Another surprise awaited us when we found a beautiful overlook with a sign that said Stephan's Ruh (Steven's Rest). After the long search for Johann Wilhelm Schreiber, I felt like I had earned a short respite, gazing out at the place he once called home.

After many years of uncertainty, it's good to know that I am indeed a Schreiber after all.

Postscript

After returning home from our vacation, I received a copy of a newspaper article about our visit to Ronshausen from Mayor Becker (shown in the blue sports coat and tie). Heinrich Tann is standing in the front row, second from the left, wearing a sports coat and cap. Rev. Nickel is also wearing a sports coat in the back row at the far right. I continue to be in contact with many of the people we met that day.

Research by Heinrich Tann revealed that Johannes Schreiber (my 2nd cousin, 7x removed) served in the Hessian auxiliaries that fought for the British during the American Revolutionary War beginning in 1775. Records of those troops show that 64 men from Ronshausen participated in the fighting, a significant number for a relatively small town. This adds indirect evidence that many people sought to emigrate to avoid the constant wars that people in this area were drawn into.

Research by Heinrich Tann revealed that Johannes Schreiber (my 2nd cousin, 7x removed) served in the Hessian auxiliaries that fought for the British during the American Revolutionary War beginning in 1775. Records of those troops show that 64 men from Ronshausen participated in the fighting, a significant number for a relatively small town. This adds indirect evidence that many people sought to emigrate to avoid the constant wars that people in this area were drawn into.

Sources

Written by Steve Schreiber in December 2012 and updated in February 2024.

Last updated February 9, 2024