Heinrich and Dorothea Döring Family

Written by Steven Schreiber

My great-grandparents, Heinrich and Dorothea Döring, were born in the German colony of Norka, Russia. Heinrich and Dorothea, like most of the colonists in Norka, are descendants of ethnic Germans from the County of Isenburg. This area is northeast of Frankfurt and part of the modern-day state of Hessen, Germany. Their ancestors immigrated to Russia in 1766 in response to a Manifesto issued by Catherine II, also known as Catherine the Great, providing incentives for European colonists to settle on the Lower Volga near the frontier town of Saratov.

Dr. Igor Pleve's book, Einwanderung in das Wolgagebiet 1764-1767 (Volume 3) lists the first settlers in Norka colony. This census list shows that 218 families, comprised of 738 people, lived in the fledgling colony at the end of December 1767.

Heinrich's 3rd great-grandparents, Johann Heinrich and Maria Elisabeth Döring, were farmers of the Reformed faith from Isenburg who were among the original group of colonists that settled in Norka, arriving on August 15, 1767. On August 29, 1766, nearly a year before they arrived in Norka, they arrived in Russia at Oranienbaum after a long voyage across the Baltic Sea from Lübeck on the north German coast. The names of all the family members, including their children, Johann Michael (age 12), Eberhardt (age 9), Anna Margaretha (age 4), and an orphan in their care, Johannes Hassenpflug, were written down by Russian clerks under the supervision of Ivan Kuhlberg. From Oranienbaum, the Döring family made the year-long journey to the lower Volga region by water and land.

Dorothea's 2nd great-grandfather, Carl Maul, was also among the founders of Norka. Carl arrived in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov, near St. Petersburg) on the Russian sailing ship "Elephant" on July 19, 1766. His transport group arrived in Norka on August 15, 1767, with the Döring family. Carl was an apprentice to Conrad Weigandt, a stocking maker from Isenburg. Weigandt was a Vorsteher (leader) of the group of colonists that settled in Norka, and the colony was originally named Weigandt in his honor. Carl and Conrad Weigandt are listed as members of the Reformed faith from Isenburg. Carl married Conrad Weigandt's daughter, Anna Margaretha.

Dr. Igor Pleve's book, Einwanderung in das Wolgagebiet 1764-1767 (Volume 3) lists the first settlers in Norka colony. This census list shows that 218 families, comprised of 738 people, lived in the fledgling colony at the end of December 1767.

Heinrich's 3rd great-grandparents, Johann Heinrich and Maria Elisabeth Döring, were farmers of the Reformed faith from Isenburg who were among the original group of colonists that settled in Norka, arriving on August 15, 1767. On August 29, 1766, nearly a year before they arrived in Norka, they arrived in Russia at Oranienbaum after a long voyage across the Baltic Sea from Lübeck on the north German coast. The names of all the family members, including their children, Johann Michael (age 12), Eberhardt (age 9), Anna Margaretha (age 4), and an orphan in their care, Johannes Hassenpflug, were written down by Russian clerks under the supervision of Ivan Kuhlberg. From Oranienbaum, the Döring family made the year-long journey to the lower Volga region by water and land.

Dorothea's 2nd great-grandfather, Carl Maul, was also among the founders of Norka. Carl arrived in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov, near St. Petersburg) on the Russian sailing ship "Elephant" on July 19, 1766. His transport group arrived in Norka on August 15, 1767, with the Döring family. Carl was an apprentice to Conrad Weigandt, a stocking maker from Isenburg. Weigandt was a Vorsteher (leader) of the group of colonists that settled in Norka, and the colony was originally named Weigandt in his honor. Carl and Conrad Weigandt are listed as members of the Reformed faith from Isenburg. Carl married Conrad Weigandt's daughter, Anna Margaretha.

Heinrich was born on November 5, 1858, the son of Heinrich Döring (1828 - 1888) and Christina Elisabeth Schleuning (1834 - 1902). Heinrich was the fourth generation born in Russia, baptized as a small child, and, in 1874, he was confirmed in the Evangelical Reformed Church of Norka. His grandfather was also named Heinrich Döring (born 1801), and his great-grandfather was Adam Döring (born about 1782), the son of Johann Michael Döring, who arrived in Norka in 1767 with his parents.

Dorothea was also among the fourth generation born in Russia when she came into the world on May 28, 1856. Dorothea was the daughter of Johannes Maul (1829 - ?) and Katharina Elisabeth Burbach (1830 - 1904). Dorothea was baptized at birth and confirmed in the Evangelical Reformed Church of Norka in 1872.

Dorothea was also among the fourth generation born in Russia when she came into the world on May 28, 1856. Dorothea was the daughter of Johannes Maul (1829 - ?) and Katharina Elisabeth Burbach (1830 - 1904). Dorothea was baptized at birth and confirmed in the Evangelical Reformed Church of Norka in 1872.

The list of settlements of the Central Statistics Committee, published in 1862, provides some insights into what Norka was like when Heinrich and Dorothea were born. The data from 1860 shows that Norka had 483 households, comprised of 3,289 males and 3,065 females, totaling 6,894 people. At the time, there was a Reformed church, one school, two markets, five tanneries, three oil mills, and 21 grain mills.

Both Heinrich and Dorothea attended school in Norka. The schools were established by the church, which owned and operated them. Religion and education were closely interrelated in the classroom because the primary textbooks were the Biblische Geschichte (Bible Stories), the Catechism, the Bible, and the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga Songbook).

Both Heinrich and Dorothea attended school in Norka. The schools were established by the church, which owned and operated them. Religion and education were closely interrelated in the classroom because the primary textbooks were the Biblische Geschichte (Bible Stories), the Catechism, the Bible, and the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga Songbook).

Heinrich was a farmer who followed the path of his ancestors. While homes and furnishings were privately owned, the land was held communally according to the Mir system. Strips of arable land were periodically re-allocated to each household based on the number of male members listed in each census revision. The reallocation was enforced by the government, which had an interest in the ability of households to pay their taxes.

Heinrich had only one brother, Konrad, who lived to adulthood (he was born in 1855 and died in 1898). According to Konrad's grandson, Roy Conrad Derring, Konrad was a butcher, and his body was discovered frozen to death on his horse-drawn sleigh while returning home from another colony or possibly from Saratov. Roy's father, Johann Konrad Döring (1896 - 1981), was Konrad's youngest son. Johann Konrad immigrated to Portland, Oregon, in 1912 and was known as "Cooney" Deering. Roy has written a story titled Konrädchen (Little Konrad) in honor of his father and the Döring family.

The exemption from military service promised to the colonists in Catherine's Manifesto of 1763 was taken away by the Russian government in 1874. Upon reaching the age of twenty-one, a young man was required to become a soldier in the Russian military. Records show that in 1879, Heinrich was enlisted as a militiaman (or reservist) in service to the Russian government.

In a story titled "Military Service," Joanne Krieger writes:

Heinrich had only one brother, Konrad, who lived to adulthood (he was born in 1855 and died in 1898). According to Konrad's grandson, Roy Conrad Derring, Konrad was a butcher, and his body was discovered frozen to death on his horse-drawn sleigh while returning home from another colony or possibly from Saratov. Roy's father, Johann Konrad Döring (1896 - 1981), was Konrad's youngest son. Johann Konrad immigrated to Portland, Oregon, in 1912 and was known as "Cooney" Deering. Roy has written a story titled Konrädchen (Little Konrad) in honor of his father and the Döring family.

The exemption from military service promised to the colonists in Catherine's Manifesto of 1763 was taken away by the Russian government in 1874. Upon reaching the age of twenty-one, a young man was required to become a soldier in the Russian military. Records show that in 1879, Heinrich was enlisted as a militiaman (or reservist) in service to the Russian government.

In a story titled "Military Service," Joanne Krieger writes:

Some of the boys eagerly looked forward to the time when they could become a soldier. When the army marched through their village, the children were delighted to watch the trained horses prance to music while the soldiers, in full uniform, arrogantly strutted by. I wonder how many young boys admired the soldier's polished boots as they looked down on their own bare feet. Occasionally, if a crowd had gathered, the soldiers would perform precise movements as the onlookers cheered! Heinrich Krieger, born 1885, told how much he enjoyed watching the horses. He said, "The horses were dancing to music right on the street." The older folks, however, did not want to acknowledge the beauty and excitement of these occasions because they felt betrayed. Not only was Catherine's promise of exemption from army duty broken, now the younger boys seemed overly fond of the idea of being a soldier. This bitterness, felt by the older generation, plus rumors of war caused many of our relatives to leave for America.

As a boy approached enlistment age, his enthusiasm waned. He now understood the army was not just parades, prancing horses, a uniform and shiny boots. Training would take him far from his familiar village, perhaps leaving a wife and small children behind.

Little is known about Heinrich's military service, but given the following events, it does not appear that he spent much time away from his home in Norka.

Heinrich and Dorothea were unmarried when their first daughter, Katharina, was born on March 9, 1879. The couple, both in their early 20s, married nearly a year later on February 26, 1880.

Shortly after their marriage, in June of 1880, one of the most significant events in the history of Norka occurred with the dedication of a magnificent new church located on 9th street. The tall, stately dome of the edifice could be seen from miles away, and Heinrich and Dorothea were surely on hand to witness this event.

Heinrich and Dorothea were unmarried when their first daughter, Katharina, was born on March 9, 1879. The couple, both in their early 20s, married nearly a year later on February 26, 1880.

Shortly after their marriage, in June of 1880, one of the most significant events in the history of Norka occurred with the dedication of a magnificent new church located on 9th street. The tall, stately dome of the edifice could be seen from miles away, and Heinrich and Dorothea were surely on hand to witness this event.

On July 13, 1880, shortly after the new church's dedication, Heinrich and Dorothea's firstborn, Katharina, died.

A son, Johann Georg, was born on December 6, 1882, but he died six months later on June 5, 1883.

A second daughter, Katharina Elisabeth, was born on March 12, 1884.

A third daughter was born on June 25, 1886. Katharina Magdalena would live a long life, as would her sibling, Katharina, who was born on July 19, 1888.

Norka continued to grow, and the 1886 Zemstvo (an elective district council in pre-revolutionary Russia) Census showed that there were now 877 households, 3,898 males and 3,743 females for a total of 7,641 people of both sexes. The population is Germans of the Reformed Faith. There were 322 families "constantly absent." These people likely emigrated to North America on six-month passports and did not return to Russia. There were 13 families (81 people) listed as outsiders (non-Germans). There were 2,127 males and 2,034 literate females. Norka had 785 inhabited houses, of which 444 were made of stone, 336 of wood, and 5 – of daub and wattle. The roofs of 78 homes were made of wood, 704 of straw, and 3 of soil. There were 54 industrial enterprises, 5 taverns and 11 stores. The settlers had 741 plows, 4,293 horses (both working and non-working), 2,602 cows and calves, 5,280 sheep, 1,686 pigs and 869 goats, and 5 bee gardens with 34 bee hives. In 1885, annual fees and duties paid to the government amounted to 24,007 rubles. There were no payments in arrears.

Tragedy again entered the lives of Heinrich and Dorothea when she gave birth to male-female fraternal twins on October 4, 1890. The son, Heinrich, likely died at birth or shortly after that, but the daughter, Elisabeth, survived.

The second daughter, Katharina Elisabeth, was eight years old when she died on July 20, 1892, followed shortly after that by the death of the twin, Elisabeth, who passed away on her second birthday, on October 4, 1892. It is unknown whether the severe famine in the region from 1891 to 1892 may have contributed to these deaths.

Less than a year later, another son named Heinrich was born on August 10, 1893. Heinrich died on July 21, 1895. It is almost unimaginable to understand the grief that Heinrich and Dorothea must have felt when they lost yet another child.

The ninth child, a daughter named Elisabeth, was born on June 19, 1899. Elisabeth is my grandmother. She would join her parents and two sisters on the journey to the New World.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, many Volga German families began to emigrate to North America. The primary reasons for emigration from Russia included:

Emigration to North America began in 1875.

A son, Johann Georg, was born on December 6, 1882, but he died six months later on June 5, 1883.

A second daughter, Katharina Elisabeth, was born on March 12, 1884.

A third daughter was born on June 25, 1886. Katharina Magdalena would live a long life, as would her sibling, Katharina, who was born on July 19, 1888.

Norka continued to grow, and the 1886 Zemstvo (an elective district council in pre-revolutionary Russia) Census showed that there were now 877 households, 3,898 males and 3,743 females for a total of 7,641 people of both sexes. The population is Germans of the Reformed Faith. There were 322 families "constantly absent." These people likely emigrated to North America on six-month passports and did not return to Russia. There were 13 families (81 people) listed as outsiders (non-Germans). There were 2,127 males and 2,034 literate females. Norka had 785 inhabited houses, of which 444 were made of stone, 336 of wood, and 5 – of daub and wattle. The roofs of 78 homes were made of wood, 704 of straw, and 3 of soil. There were 54 industrial enterprises, 5 taverns and 11 stores. The settlers had 741 plows, 4,293 horses (both working and non-working), 2,602 cows and calves, 5,280 sheep, 1,686 pigs and 869 goats, and 5 bee gardens with 34 bee hives. In 1885, annual fees and duties paid to the government amounted to 24,007 rubles. There were no payments in arrears.

Tragedy again entered the lives of Heinrich and Dorothea when she gave birth to male-female fraternal twins on October 4, 1890. The son, Heinrich, likely died at birth or shortly after that, but the daughter, Elisabeth, survived.

The second daughter, Katharina Elisabeth, was eight years old when she died on July 20, 1892, followed shortly after that by the death of the twin, Elisabeth, who passed away on her second birthday, on October 4, 1892. It is unknown whether the severe famine in the region from 1891 to 1892 may have contributed to these deaths.

Less than a year later, another son named Heinrich was born on August 10, 1893. Heinrich died on July 21, 1895. It is almost unimaginable to understand the grief that Heinrich and Dorothea must have felt when they lost yet another child.

The ninth child, a daughter named Elisabeth, was born on June 19, 1899. Elisabeth is my grandmother. She would join her parents and two sisters on the journey to the New World.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, many Volga German families began to emigrate to North America. The primary reasons for emigration from Russia included:

- Russification movements by the government meant the potential elimination of the German language and culture

- Land shortages

- Loss of privileges granted in Catherine's Manifesto, not the least of which meant that young men were now subject to compulsory military service

- Recruitment by New World countries

Emigration to North America began in 1875.

Among the scouting party sent to the United States by the Colonies in 1874, to seek land, were two men from Norka: Johannes Krieger and Johannes Nolde. Their reports on return soon set in motion emigration which started as early as 1875, with seven Norka families who came to Ohio and two years later went to Sutton, Nebraska. In 1876, one the largest Protestant groups of colonists ever to emigrate, was a group of eighty-five families, most of them from Norka."

from "The Czar's Germans," by Hattie Plum Williams

We don't know precisely why Heinrich and Dorothea made the difficult decision to leave friends and family in Norka, but it seems certain that they were searching for a better life for themselves and their children. Perhaps, as they reached their mid-forties, they decided it was becoming too difficult to continue farming without any sons to assist, knowing that the daughters would likely marry and move into the husband's household. They probably received letters from friends and family in North America encouraging them to come. After much thought, Heinrich and Dorothea made a decision in 1903 to immigrate to the United States and began the process of obtaining the necessary permissions.

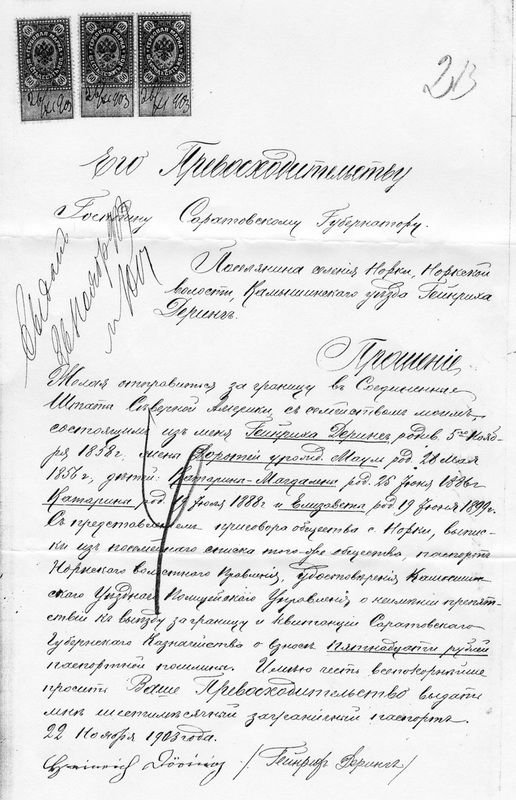

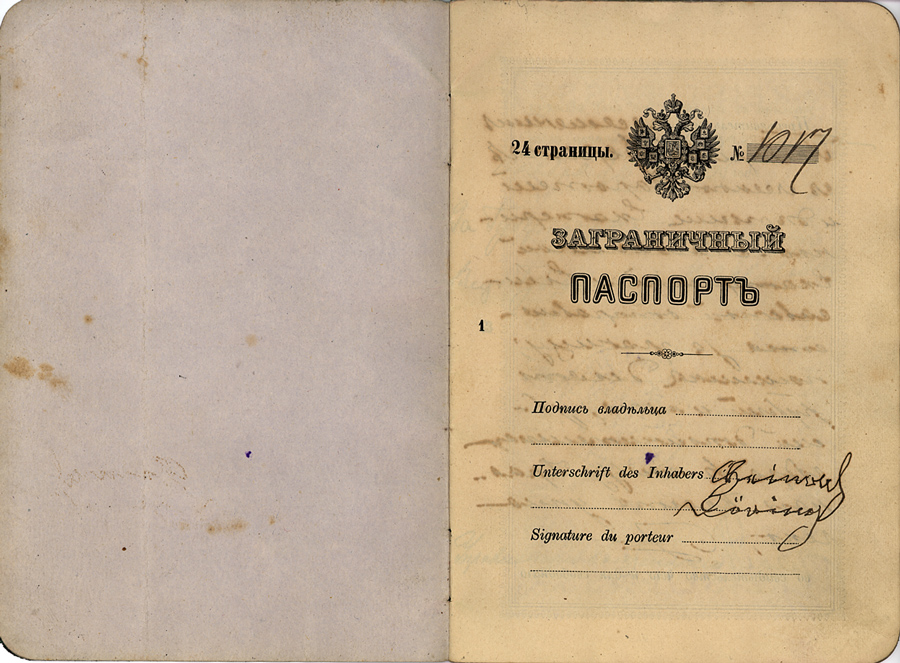

To obtain a foreign travel passport, Heinrich was required to submit an application to the provincial governor of Saratov and pay 15 rubles. The application includes six documents.

The first document is a letter signed by Heinrich to the Governor of Saratov requesting a six-month foreign passport to travel to the United States. The actual letter, signed by Heinrich, is shown below:

To obtain a foreign travel passport, Heinrich was required to submit an application to the provincial governor of Saratov and pay 15 rubles. The application includes six documents.

The first document is a letter signed by Heinrich to the Governor of Saratov requesting a six-month foreign passport to travel to the United States. The actual letter, signed by Heinrich, is shown below:

The second document is from the State Treasury of Saratov Province, indicating receipt of 15 rubles for a six-month foreign passport.

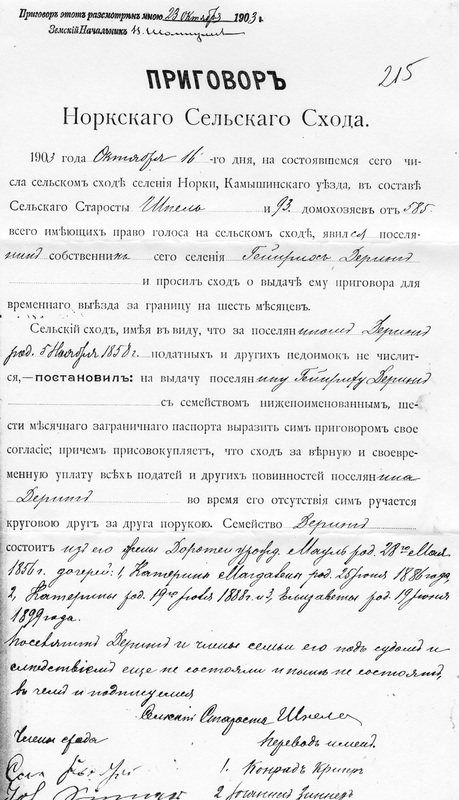

The third document is a "Verdict" from the Norka Volost (a Volost is a small rural district) granting permission to leave the community. At a Volost meeting on October 16, 1903 led by Elderman Spel (the spelling of this surname may be incorrect and could possibly be "Schnell") and representatives from 93 of the 585 households who have the right to vote, Heinrich made an appearance to request permission for temporary departure abroad for six months. The verdict for a six-month departure matched Heinrich's application for a six-month foreign passport. Requesting a six-month passport was common for those traveling to America, even though they had no intention of returning to Russia. The six-month passport was simply less expensive than an extended passport. The Volost determined that Heinrich had no taxes or other payments in arrears. It was also documented that he had never been on trial or under investigation or prosecution. The village Elderman and 32 council members signed the document indicating their approval of Heinrich's request.

The third document is a "Verdict" from the Norka Volost (a Volost is a small rural district) granting permission to leave the community. At a Volost meeting on October 16, 1903 led by Elderman Spel (the spelling of this surname may be incorrect and could possibly be "Schnell") and representatives from 93 of the 585 households who have the right to vote, Heinrich made an appearance to request permission for temporary departure abroad for six months. The verdict for a six-month departure matched Heinrich's application for a six-month foreign passport. Requesting a six-month passport was common for those traveling to America, even though they had no intention of returning to Russia. The six-month passport was simply less expensive than an extended passport. The Volost determined that Heinrich had no taxes or other payments in arrears. It was also documented that he had never been on trial or under investigation or prosecution. The village Elderman and 32 council members signed the document indicating their approval of Heinrich's request.

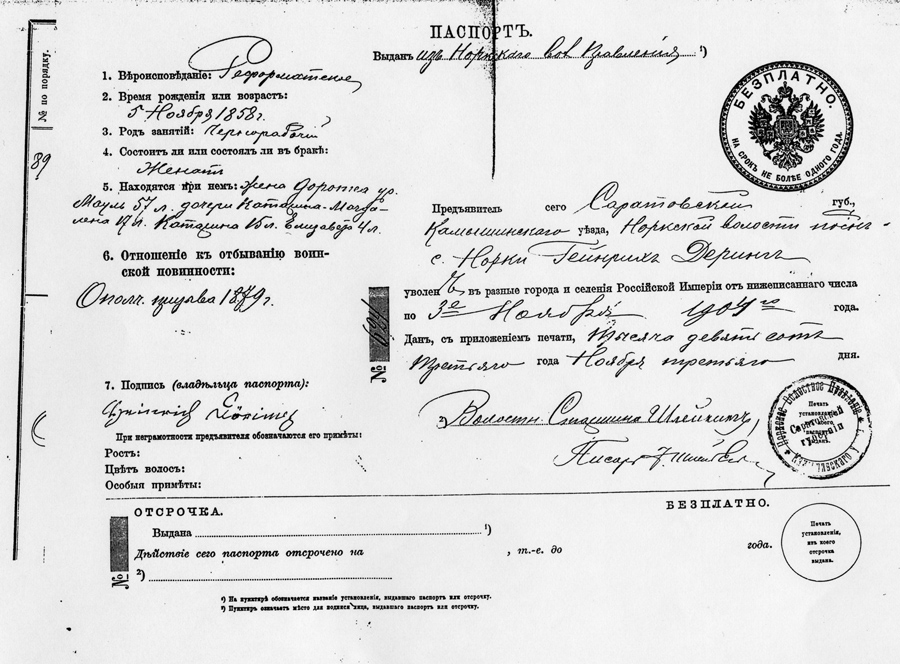

The colony of Norka was part of the Kamyshinsky District. The fourth document in the passport application is from the Kamyshinsky District police office, dated November 7, 1903, verifying that they have no objections to Heinrich and his family applying for a foreign passport. This document was signed by the District Police Officer and his secretary, noting that "Crown Stamp Duty" has been paid.

The fifth document is an extract from the Norka Family's Record List compiled in 1887, providing information about the Döring family members and their listing in the census records. It is signed by the Norka Volost Elderman and Volost Clerk.

The sixth and final document in the foreign passport application is an internal passport issued by the Norka Volost administration granting a release to Heinrich and his family to travel to "various cities and villages of the Russian Empire" for one year, ending November 3, 1904. There was also a fee for this document paid to the Volost Assessor.

The fifth document is an extract from the Norka Family's Record List compiled in 1887, providing information about the Döring family members and their listing in the census records. It is signed by the Norka Volost Elderman and Volost Clerk.

The sixth and final document in the foreign passport application is an internal passport issued by the Norka Volost administration granting a release to Heinrich and his family to travel to "various cities and villages of the Russian Empire" for one year, ending November 3, 1904. There was also a fee for this document paid to the Volost Assessor.

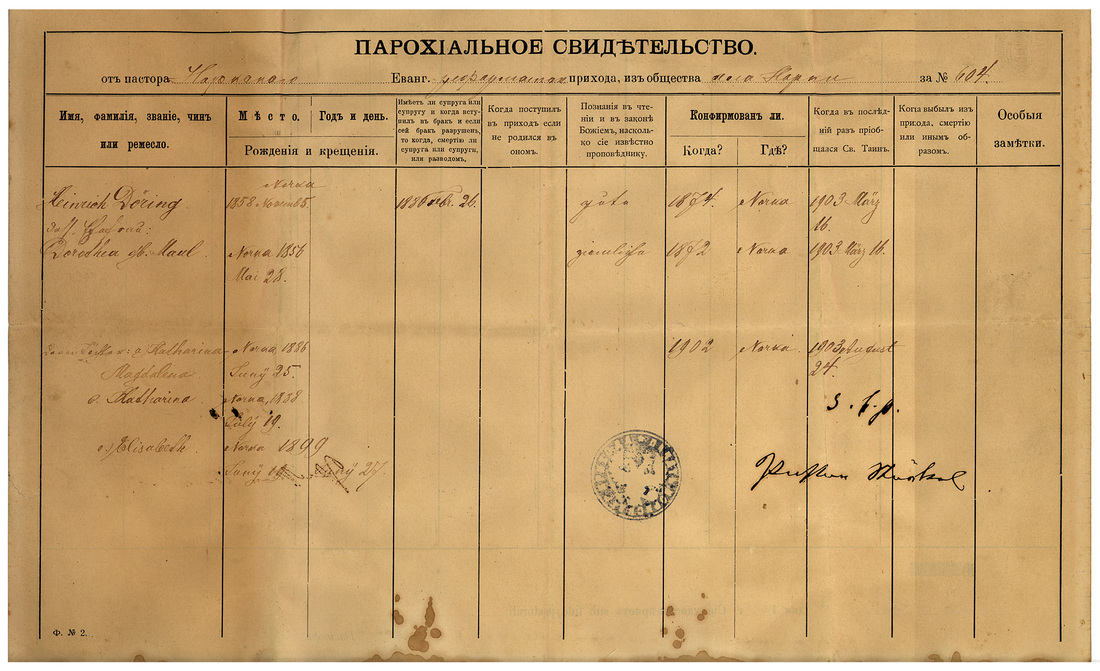

Before they departed from Norka, Heinrich and Dorothea also obtained a Parochialschein (Parish Certificate) from the Evangelical Reformed Church in Norka.

The Parochialschein shown above was issued on November 19, 1903, as documentation for the Döring family as they began their emigration from Russia to the United States. The certificate is an extract of the Norka parish list and was signed by Rev. Wilhelm Stärkel. The document provides the dates of birth, confirmation, marriage, and last communion for Heinrich, Dorothea, and their three daughters: Katharina Magdalena, Katharina, and Elisabeth. The document also indicates that Heinrich's knowledge of the Holy Writ is "good" and Dorothea's is "fair." The Parochialschein was both a form of identification and an introduction for the family to its new church in the United States.

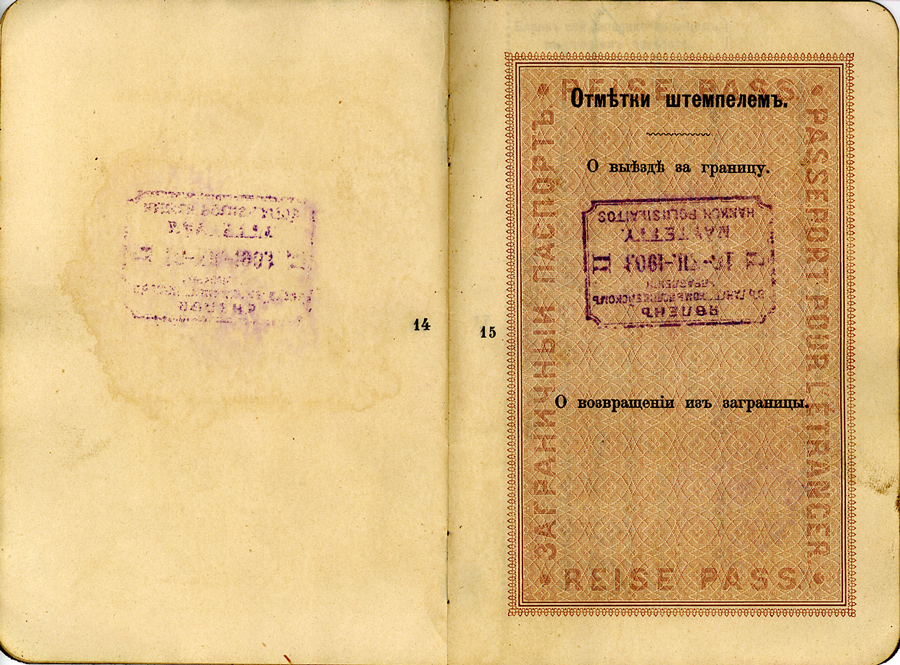

Along with their three daughters (two teenagers and a four-year-old), Heinrich and Dorothea set out in late November of 1903 for a new life in the United States. Given the time of year, it is likely that they first traveled 45 miles from Norka to the city of Saratov by horse-drawn sleigh. In Saratov, they had to obtain a foreign passport from the provincial government. The passport was issued on November 26, 1903. At the time, Russian law allowed a family to travel under a single passport.

Along with their three daughters (two teenagers and a four-year-old), Heinrich and Dorothea set out in late November of 1903 for a new life in the United States. Given the time of year, it is likely that they first traveled 45 miles from Norka to the city of Saratov by horse-drawn sleigh. In Saratov, they had to obtain a foreign passport from the provincial government. The passport was issued on November 26, 1903. At the time, Russian law allowed a family to travel under a single passport.

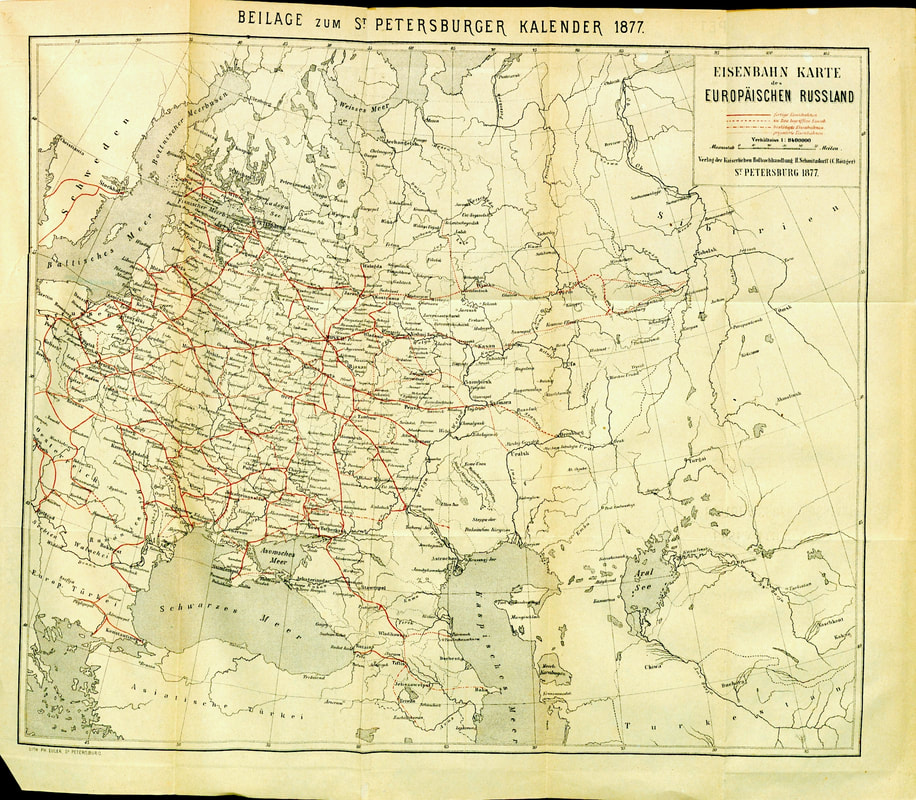

From Saratov, they likely traveled by train to Moscow and then to St. Petersburg. They probably traveled by rail from St. Petersburg to the port city of Hanko (Hangö), Finland. The rail lines connecting all of these locations were in place by 1877 (see map below).

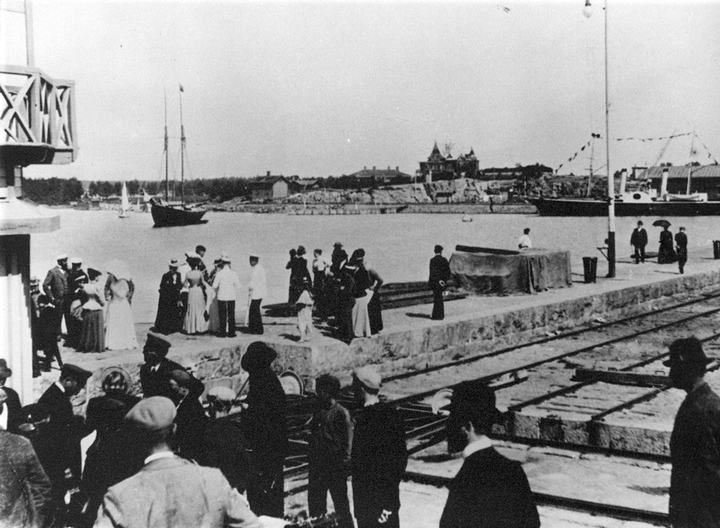

Hanko, Finland, was part of the Russian Empire from 1809 until the beginning of World War I in 1914. Finland had its own parliament, but its ruler was the Russian Czar. Hanko was a major port in 1903 that was used by many Russian citizens as a point of emigration to the Americas and other parts of the world. Many ships leaving Hanko traveled to England, where emigrants boarded larger ships for the Atlantic crossings. Hanko was used because it was the only Russian port that was free of ice for most of the winter. This was especially important for winter departures such as the one made by the Döring family.

Emigrants passing through Hanko stayed at a special hotel built in 1902 to accommodate up to 300 travelers. Coffee and buns were offered in the mornings. The Dörings would have arrived at the hotel a day or two before the departure by steamship.

The United States passed a new emigration law in 1903 to ensure that only healthy people came into the country. Only "Healthy brains and working hands" were wanted in the New World. A doctor's surgery was established at the Emigrant Hotel in 1903 so that passengers would not make the journey in vain.

Heinrich and Dorothea would have also paid a visit to the Emigrants' Office at 15 Boulevard Street, where they had to fill out a questionnaire and write their names, legal domicile, destination of journey, and information from their passports.

Tickets were bought at the Emigrants' Office. Many tickets were purchased by relatives or friends in America. This seems to have been the case for the Döring family based on an entry in the arrival records in the United States indicating that a friend in Portland had paid for the passage. According to The Museum of Hanko, the ticket price was the same as farmer's salary for 3 to 4 months. Heinrich and Dorothea needed five tickets.

The emigrants were required to take money with them on the voyage. The sum required was 50 dollars, and there were several banks in Hanko to provide a bill of exchange that was turned into cash at the destination harbor.

Small shops were located near the hotel and banks where Heinrich and Dorothea could purchase food and other items for the voyage.

The United States passed a new emigration law in 1903 to ensure that only healthy people came into the country. Only "Healthy brains and working hands" were wanted in the New World. A doctor's surgery was established at the Emigrant Hotel in 1903 so that passengers would not make the journey in vain.

Heinrich and Dorothea would have also paid a visit to the Emigrants' Office at 15 Boulevard Street, where they had to fill out a questionnaire and write their names, legal domicile, destination of journey, and information from their passports.

Tickets were bought at the Emigrants' Office. Many tickets were purchased by relatives or friends in America. This seems to have been the case for the Döring family based on an entry in the arrival records in the United States indicating that a friend in Portland had paid for the passage. According to The Museum of Hanko, the ticket price was the same as farmer's salary for 3 to 4 months. Heinrich and Dorothea needed five tickets.

The emigrants were required to take money with them on the voyage. The sum required was 50 dollars, and there were several banks in Hanko to provide a bill of exchange that was turned into cash at the destination harbor.

Small shops were located near the hotel and banks where Heinrich and Dorothea could purchase food and other items for the voyage.

The Döring family of five departed on December 16, 1903, from Hanko to Helsinki, Finland, on the steamship Polaris (sailing for the Finland Steamship Company). The departure was both solemn and festive. The emigrants came to the harbor from the Emigrant Hotel in rows led by the hotel's caretaker. The departing passengers were modestly dressed, but many put flowers or greens on their luggage to celebrate their departure. Citizens from Hanko often came to see the ships depart. Passengers often sang songs or hymns as the ship slid away from the dock. A new life of possibilities was waiting.

This was probably the Döring's first time aboard a steamship and certainly their first experience at sea. From Helsinki, the family continued sailing on the Polaris to Copenhagen, Denmark, and from there to the Port of Hull on the east coast of England. The Polaris was put into service in 1899, and the ship was designed to operate in difficult ice conditions, minimizing cancellations.

According to Nicholas J. Evans in his article titled "Migration from Northern Europe to America via the Port of Hull, 1848-1914", the journey from mainland Europe to the United Kingdom was an ordeal for the emigrants. The sailing vessels were cramped, their timings irregular, and the frequency of the North Sea crossings rendered them unsuitable for the movement of substantial numbers of trans migrants.

The town of Kingston upon Hull lies at the point where the River Hull and River Humber meet. Throughout its history, the port enjoyed successful trade links with most of the ports of Northern Europe. Most of the emigrants entering Hull traveled via the Paragon Railway Station and, from there, traveled to Liverpool via Leeds, Huddersfield, and Stalybridge (just outside Manchester). The train tickets were part of a package that included the steamship ticket to Hull, a train ticket to Liverpool, and then the steamship ticket to their final destination - mainly America. Sometimes, so many emigrants arrived at one time that up to 17 carriages were pulled by one steam engine. All the baggage was stored in the rear 4 carriages, with the passengers filling the carriages nearer the front of the train. The trains took precedence over all other train services because of their length and usually left Hull on a Monday morning around 11.00 a.m., arriving in Liverpool between 2.00 and 3.00 pm.

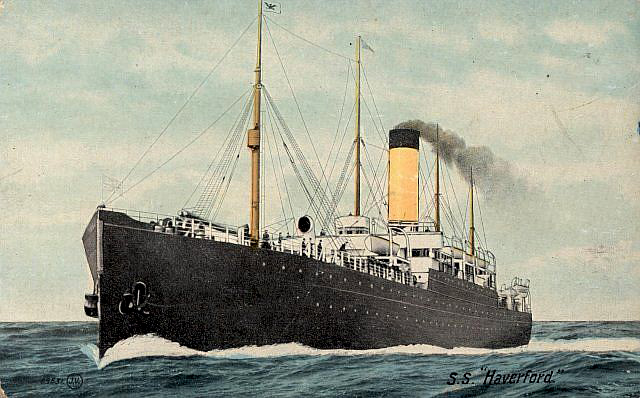

In Liverpool, the Döring family boarded the steamship Haverford, sailing for the American Line at that time. The Haverford departed as scheduled from Liverpool on December 23, 1903, and began the Transatlantic crossing during the stormy winter season. The family must have celebrated Christmas onboard the Haverford despite the difficult conditions.

The Haverford was built in 1901 by John Brown & Co. Ltd. of Glasgow for the American Line. There was accommodation for 150 2nd and 1,700 3rd class passengers. She was launched on April 5, 1901, and sailed on her maiden voyage under the British flag. The Döring family traveled in the 3rd class section of the ship where crowded conditions were the norm.

It must have been a wonderful and anxious moment as the Haverford rounded the Cape May lighthouse and sailed up the Delaware River to Philadelphia on January 5, 1904. After nearly six weeks of travel from Norka, the Döring family was finally in America.

Fredric M. Miller provides insights into the experiences of Heinrich and Dorothea in his article titled Philadelphia: Immigrant City.

The town of Kingston upon Hull lies at the point where the River Hull and River Humber meet. Throughout its history, the port enjoyed successful trade links with most of the ports of Northern Europe. Most of the emigrants entering Hull traveled via the Paragon Railway Station and, from there, traveled to Liverpool via Leeds, Huddersfield, and Stalybridge (just outside Manchester). The train tickets were part of a package that included the steamship ticket to Hull, a train ticket to Liverpool, and then the steamship ticket to their final destination - mainly America. Sometimes, so many emigrants arrived at one time that up to 17 carriages were pulled by one steam engine. All the baggage was stored in the rear 4 carriages, with the passengers filling the carriages nearer the front of the train. The trains took precedence over all other train services because of their length and usually left Hull on a Monday morning around 11.00 a.m., arriving in Liverpool between 2.00 and 3.00 pm.

In Liverpool, the Döring family boarded the steamship Haverford, sailing for the American Line at that time. The Haverford departed as scheduled from Liverpool on December 23, 1903, and began the Transatlantic crossing during the stormy winter season. The family must have celebrated Christmas onboard the Haverford despite the difficult conditions.

The Haverford was built in 1901 by John Brown & Co. Ltd. of Glasgow for the American Line. There was accommodation for 150 2nd and 1,700 3rd class passengers. She was launched on April 5, 1901, and sailed on her maiden voyage under the British flag. The Döring family traveled in the 3rd class section of the ship where crowded conditions were the norm.

It must have been a wonderful and anxious moment as the Haverford rounded the Cape May lighthouse and sailed up the Delaware River to Philadelphia on January 5, 1904. After nearly six weeks of travel from Norka, the Döring family was finally in America.

Fredric M. Miller provides insights into the experiences of Heinrich and Dorothea in his article titled Philadelphia: Immigrant City.

Although it began serving New York in the 1890s, the American Line never abandoned Philadelphia, adding ships with such local names as the Kensington, Southwark, Haverford, and Merion to the Philadelphia run around the turn of the century. By then the American Line's prosperity was firmly based on the new waves of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe who sailed to America from British ports. It transported most of the roughly 20,000 immigrants arriving at Philadelphia each year between 1880 and 1910.

Almost all immigrants made their first contact with America at the piers and immigrant stations and according to all accounts, for most who came through Philadelphia that was their only contact with the city, for relatives or employers quickly took them elsewhere. From the 1870's through the early 1920's the waterfront was a bustling place, especially around the Washington Avenue wharves where the American and Red Star Lines docked. This was an area of warehouses, factories, sugar refineries, freight depots, and grain elevators, all connected to the vast yards of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The railroad owned the wharves, and because it effectively controlled the immigrant traffic, in the 1870's it had constructed a two-story facility for receiving immigrants. Having already had their medical examinations downriver, at Washington Avenue the immigrants passed through customs inspections and then went downstairs to a ticket office and reception area from when they could board trains and leave the city.

As immigration increased, it outgrew the capacity of the Washington Avenue building. In 1896 the railroad spent $10,000 to expand that capacity from 300 to 1,500 people and to modernize the whole facility, equipping it with electric lights and steam heat. Passengers now disembarked directly into the building's second story for what may have been their third medical examination and questioning. The first floor had a ticket office, money exchange, women's dressing room, waiting room, and travel information bureau. As up to eight inspectors greeted each ship, it was estimated that 300 English-speaking or 150 non-English-speaking passengers could be processed each hour.

Outside, there was usually a crowd of entrepreneurs eager to charge the newcomers exorbitant rates for a variety of needed and unneeded services.

According to the ship's arrival manifest, the family was in good condition with $18 and train tickets to Portland, Oregon. In Portland, they planned to meet relatives from Norka, Peter, and Christina Bauer, who resided at 763 North Mallory Avenue. Christina (née Maul) was the sister of Dorothea. Christina (born 1870) and Peter (born 1868) arrived in the United States in 1899 and immediately settled in Portland.

Listed next to the Döring family on the Haverford's manifest are Jacob and Katharina Sterkel, who are destined to join Jacob's brother-in-law, Adam Schwartz, in Portland. It is likely that the Sterkel's were also from Norka and planned to join the already large group of immigrants from that colony who, since 1882, had settled in Portland's Albina district in an area called "Little Russia".

Listed next to the Döring family on the Haverford's manifest are Jacob and Katharina Sterkel, who are destined to join Jacob's brother-in-law, Adam Schwartz, in Portland. It is likely that the Sterkel's were also from Norka and planned to join the already large group of immigrants from that colony who, since 1882, had settled in Portland's Albina district in an area called "Little Russia".

According to the passenger records of the Finland Steamship Company, the price of the ticket from Helsinki, Finland, to Portland, Oregon, was $355.25 for the entire family. This was a substantial sum in 1903 and is the equivalent of $8,930 in 2010 based on the growth in the Consumer Price Index. The Haverford manifest indicates that the passage was paid by a "friend" - likely the same Peter Bauer noted above.

The cross-country train trip from the port in Philadelphia to the station in Portland lasted several more days and may have been difficult given the winter season.

It was customary for friends and family to meet the new arrivals in Portland at the train station, and it is likely that Peter and Christina Bauer, as well as other family and friends from Russland, met the Döring family when they arrived. For Heinrich, Dorothea, and the children, it had been a journey unlike any other they had experienced and one they would never forget.

The Döring family initially resided at 763 Mallory Avenue. The property was owned by Peter Bauer, Dorothea's brother-in-law. Both families were members of the Free Evangelical Brethren Church. Around 1900, members of the fledgling congregation agreed to construct a small house of worship building on Peter Bauer's property, agreeing that after no more than five years, the building ownership would revert to Bauer. Bauer was the nephew of Elder Peter Yost. Grandson Fred Schreiber recalled that Henry and Dora renovated this building into a residence shortly after they arrived in Portland. When a decision was made to build a larger church on the property in 1907, the Döring family moved into a home at 803 East 6th North (now 3817 NE 6th Avenue). The City of Portland records show that the home was built that year.

While the Volga German colonies of Frank and Balzer were well represented in Portland, with Norka, some say it was almost as if the place had picked itself up and moved halfway around the world. Dozens of former neighbors once again lived and worked side by side. This Old World microcosm stretched along Northeast Union and Seventh avenues from Fremont to Shaver. Here, one could see women clad in brown or black woolen shawls and head scarves, talking in their old Hessian dialect while their children played games from the Old Country.

Portland must have seemed very different with its temperate weather, tall fir trees, and frequent rainfall - so very different from the vast Russian steppe where they were born and had lived their entire lives up to this time.

Even though Portland was a small city at the time (population 90,426 in 1900), adapting to urban life must have been a significant change from Norka's more rural environment.

The cross-country train trip from the port in Philadelphia to the station in Portland lasted several more days and may have been difficult given the winter season.

It was customary for friends and family to meet the new arrivals in Portland at the train station, and it is likely that Peter and Christina Bauer, as well as other family and friends from Russland, met the Döring family when they arrived. For Heinrich, Dorothea, and the children, it had been a journey unlike any other they had experienced and one they would never forget.

The Döring family initially resided at 763 Mallory Avenue. The property was owned by Peter Bauer, Dorothea's brother-in-law. Both families were members of the Free Evangelical Brethren Church. Around 1900, members of the fledgling congregation agreed to construct a small house of worship building on Peter Bauer's property, agreeing that after no more than five years, the building ownership would revert to Bauer. Bauer was the nephew of Elder Peter Yost. Grandson Fred Schreiber recalled that Henry and Dora renovated this building into a residence shortly after they arrived in Portland. When a decision was made to build a larger church on the property in 1907, the Döring family moved into a home at 803 East 6th North (now 3817 NE 6th Avenue). The City of Portland records show that the home was built that year.

While the Volga German colonies of Frank and Balzer were well represented in Portland, with Norka, some say it was almost as if the place had picked itself up and moved halfway around the world. Dozens of former neighbors once again lived and worked side by side. This Old World microcosm stretched along Northeast Union and Seventh avenues from Fremont to Shaver. Here, one could see women clad in brown or black woolen shawls and head scarves, talking in their old Hessian dialect while their children played games from the Old Country.

Portland must have seemed very different with its temperate weather, tall fir trees, and frequent rainfall - so very different from the vast Russian steppe where they were born and had lived their entire lives up to this time.

Even though Portland was a small city at the time (population 90,426 in 1900), adapting to urban life must have been a significant change from Norka's more rural environment.

Heinrich (Henry) obtained employment with the railroad as a freight car repairman. During a period when the union members went on strike, Henry continued to work, staying at the shop around the clock. His daughter, Elisabeth, would deliver his lunch. After the strike ended, the union made sure that Henry was no longer employed. He lost both his job and his retirement benefits.

Henry and another fellow had a horse, wagon, and steam-powered saw. In the summer, they would cut firewood and sell it in the neighborhood. This helped bring in some money to the household, but getting by was often difficult.

Dorothea (Dora) maintained the household and took care of the three girls. The spelling of the family name was changed to Dering or Derring as, presumably, this would cause English speakers to pronounce Döring in the same phonetic way that it sounds in the Volga German dialect.

Katharina Magdalena (Lena) married Gottfried Gräb around 1905, and they soon had a daughter named Lydia. Lydia and my grandmother, Elisabeth, were good childhood friends.

Lena and Gottfried had a second daughter, Esther, born in May 1914.

Henry and another fellow had a horse, wagon, and steam-powered saw. In the summer, they would cut firewood and sell it in the neighborhood. This helped bring in some money to the household, but getting by was often difficult.

Dorothea (Dora) maintained the household and took care of the three girls. The spelling of the family name was changed to Dering or Derring as, presumably, this would cause English speakers to pronounce Döring in the same phonetic way that it sounds in the Volga German dialect.

Katharina Magdalena (Lena) married Gottfried Gräb around 1905, and they soon had a daughter named Lydia. Lydia and my grandmother, Elisabeth, were good childhood friends.

Lena and Gottfried had a second daughter, Esther, born in May 1914.

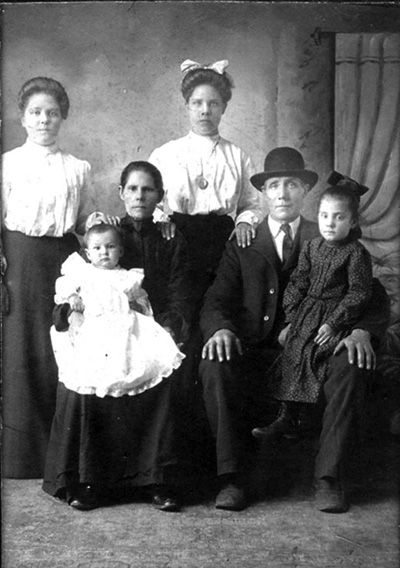

Heinrich and Dorothea Döring Family

Seated from left to right: Dorothea (nee Maul) Döring holding Lydia Gräb, the daughter of Magdalena Döring and her first husband, Gottfried Gräb; Heinrich Döring (Henry Derring) holding Elisabeth Derring.

Standing from left to right: Magdalena (nee Döring) Gräb and Katharine Döring.

Gottfried Gräb died in 1915.

Lena married Joseph Abranz, and they celebrated the birth of a son, Robert, in 1916.

Lena's sister Katharina (Katy) married John Kiltow (Külthau or Kildau), also from Norka, in December 1908, and their son, Roy, was born in 1912.

Elisabeth, who was only 4 years old when she arrived in Portland, grew up speaking only German in the household but also learning English in her new environment. Elisabeth attended the Free Evangelical Brethren Church in Portland and was confirmed in 1914.

Lena married Joseph Abranz, and they celebrated the birth of a son, Robert, in 1916.

Lena's sister Katharina (Katy) married John Kiltow (Külthau or Kildau), also from Norka, in December 1908, and their son, Roy, was born in 1912.

Elisabeth, who was only 4 years old when she arrived in Portland, grew up speaking only German in the household but also learning English in her new environment. Elisabeth attended the Free Evangelical Brethren Church in Portland and was confirmed in 1914.

In 1918, Elisabeth married my grandfather, Gottfried Schreiber, a native of Norka. Elisabeth and Gottfried were blessed with the birth of four children: Frederick in 1919, Walter in 1921, Bernice in 1924, and Vernon in 1942.

Henry and Dora were surrounded by their children and grandchildren, who lived nearby.

The involvement of the United States in World War I in 1917 made ethnic German Americans targets of anti-German sentiments and suspicion in some parts of the Pacific Northwest. Given that Henry and Dora lived in a predominantly Volga German neighborhood, the impacts were likely to be limited.

Certainly, the entire family would have had great anxiety about the impacts of the Bolshevik Revolution on their family and friends back in Norka. Little did they know that the Iron Curtain would soon fall, severing communication with those in Russia and imposing a communist doctrine on the people of Norka, who had led mainly independent lives since they arrived in the 1760s.

Henry became a naturalized citizen in 1918. In the 1920 and 1930 U.S. Census lists, the family continues living at 803 East 6th Street (now 3817 NE 6th) in Portland. At the back of the same property, they built a smaller house in which daughter Katy and her husband, John Kiltow, lived.

Henry and Dora were surrounded by their children and grandchildren, who lived nearby.

The involvement of the United States in World War I in 1917 made ethnic German Americans targets of anti-German sentiments and suspicion in some parts of the Pacific Northwest. Given that Henry and Dora lived in a predominantly Volga German neighborhood, the impacts were likely to be limited.

Certainly, the entire family would have had great anxiety about the impacts of the Bolshevik Revolution on their family and friends back in Norka. Little did they know that the Iron Curtain would soon fall, severing communication with those in Russia and imposing a communist doctrine on the people of Norka, who had led mainly independent lives since they arrived in the 1760s.

Henry became a naturalized citizen in 1918. In the 1920 and 1930 U.S. Census lists, the family continues living at 803 East 6th Street (now 3817 NE 6th) in Portland. At the back of the same property, they built a smaller house in which daughter Katy and her husband, John Kiltow, lived.

During the 1920-24 famine period in the Volga region, Henry and Dora must have once again agonized over the fate of their friends and family. Letters published in Die Welt-Post regarding the conditions in Russia are heart-wrenching. Henry and Dora participated in the Volga Relief Society that was formed in Portland to help those starving in Norka and the other German colonies.

Henry and Dora began to attend the Zion Congregational Church and are listed as members in the 1925 church records.

Henry and Dora began to attend the Zion Congregational Church and are listed as members in the 1925 church records.

As the Great Depression ended the prosperity of the 1920s, the Pacific Northwest suffered economic catastrophe like the rest of the country. Businesses and banks failed; by 1933, only about half as many people were working as had been in 1926. Early in the Depression, the family packed a large trunk and took a train to St. Paul, Oregon, where they worked picking hops to earn income. Later, Henry and Dora's grandsons, Fred and Walter, joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, which provided unemployment relief for several million young Americans.

Henry and his grandson, Fred Schreiber, had a close relationship. Fred greatly admired his grandfather, who would pick him up and care for him after school when his parents were at work. Sometimes, Henry would stop for a shot of whiskey with one of the local bootleggers. According to Fred, Henry had a gift for mathematics and could add, subtract, multiply, or divide any group of numbers that were given to him without pen and paper. Fred was in the Army when Henry fell ill in the spring of 1942. He was told that his grandfather called for him as life began to slip away. Fred tried desperately to get home in time for one last visit but to no avail.

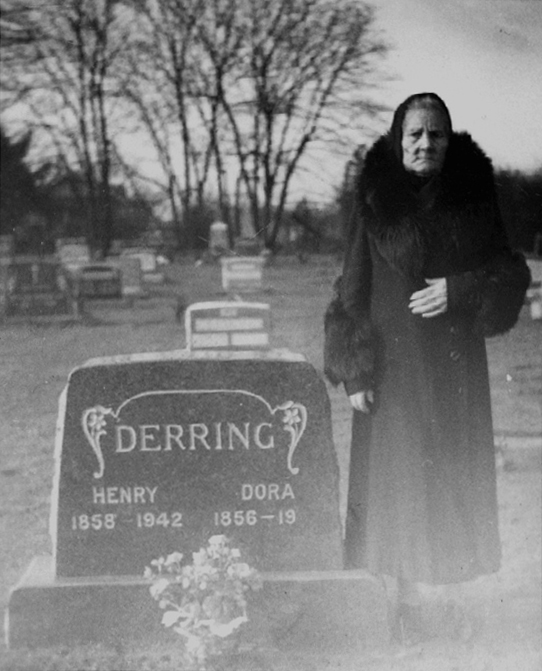

Henry died on April 29, 1942, from heart disease at the age of 83. Henry's obituary, written by Rev. Heinrich Hagelganz in the May 28, 1942 publication of Der Kirchenbote, notes that he and Dora had been married for 62 years and that "he died believing in his Savior."

Henry and his grandson, Fred Schreiber, had a close relationship. Fred greatly admired his grandfather, who would pick him up and care for him after school when his parents were at work. Sometimes, Henry would stop for a shot of whiskey with one of the local bootleggers. According to Fred, Henry had a gift for mathematics and could add, subtract, multiply, or divide any group of numbers that were given to him without pen and paper. Fred was in the Army when Henry fell ill in the spring of 1942. He was told that his grandfather called for him as life began to slip away. Fred tried desperately to get home in time for one last visit but to no avail.

Henry died on April 29, 1942, from heart disease at the age of 83. Henry's obituary, written by Rev. Heinrich Hagelganz in the May 28, 1942 publication of Der Kirchenbote, notes that he and Dora had been married for 62 years and that "he died believing in his Savior."

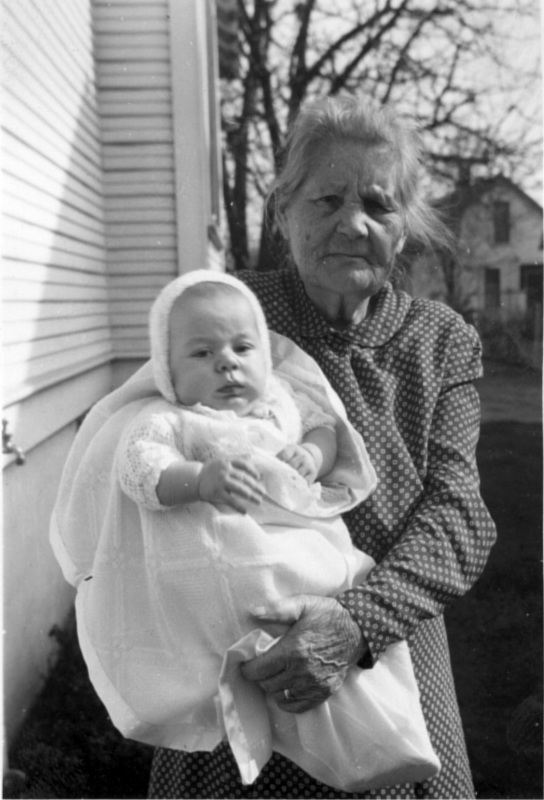

After Henry's passing, Dora lived a full life in the households of her three daughters and many grandchildren. She claimed that she didn't understand English, but some say she may have known more than she let on.

Dora died on May 29, 1955, just one day past her 99th birthday. It is believed that she suffered from Alzheimer's Disease in her later years. The following text from her obituary, written by Pastor H. G. Zorn and published in the July 14, 1955 edition of Der Kirchenbote, seems to confirm this belief: "In her last years, she returned to a child-like state, and required allowances for her condition, and care, large sacrifices and devotions from her daughters, Mrs. John Kiltow and Mrs. Gottfried Schreiber who shared the duties for her care." The obituary says: "She is survived by her three daughters and their husbands, six grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren, along with countless relatives and friends."

Both Dora and Heinrich's obituaries state that they had twelve children and that only the three daughters survived them. This fact is also supported by a note written by my mother, Esther Schreiber. While I have not been able to identify the three missing children in the Norka or Portland birth records, I presume this knowledge was passed down from Heinrich and Dorothea to their daughters.

Henry and Dora are buried at the Rose City Cemetery in Portland. Surely, they knew that they had made the right choice to come to the United States in 1903. Despite the many hardships, life was better for the family in America. I am thankful for their courage and sacrifices. Ruhe in Frieden - Rest in Peace.

Dora died on May 29, 1955, just one day past her 99th birthday. It is believed that she suffered from Alzheimer's Disease in her later years. The following text from her obituary, written by Pastor H. G. Zorn and published in the July 14, 1955 edition of Der Kirchenbote, seems to confirm this belief: "In her last years, she returned to a child-like state, and required allowances for her condition, and care, large sacrifices and devotions from her daughters, Mrs. John Kiltow and Mrs. Gottfried Schreiber who shared the duties for her care." The obituary says: "She is survived by her three daughters and their husbands, six grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren, along with countless relatives and friends."

Both Dora and Heinrich's obituaries state that they had twelve children and that only the three daughters survived them. This fact is also supported by a note written by my mother, Esther Schreiber. While I have not been able to identify the three missing children in the Norka or Portland birth records, I presume this knowledge was passed down from Heinrich and Dorothea to their daughters.

Henry and Dora are buried at the Rose City Cemetery in Portland. Surely, they knew that they had made the right choice to come to the United States in 1903. Despite the many hardships, life was better for the family in America. I am thankful for their courage and sacrifices. Ruhe in Frieden - Rest in Peace.

Source

Written by Steven Schreiber in July 2010 and updated in November 2023. Documents and photographs provided by Steven Schreiber unless otherwise indicated.

If you have additional information or questions about this family, please Contact Us.

If you have additional information or questions about this family, please Contact Us.

Last updated November 29, 2023