Community > Homesites

Homesites

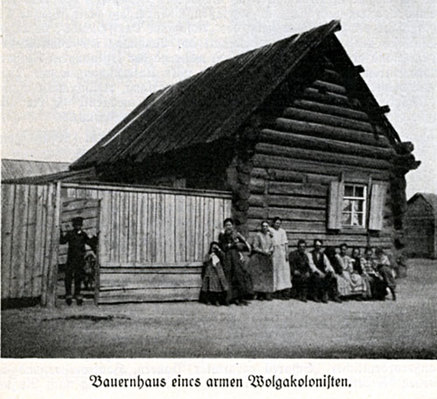

Since Norka was a Crown colony (established directly by the Russian government rather than recruiters), it is likely that some wooden houses, known as Krone Häuser (Crown Homes), had already been built by local carpenters when the colonists arrived in 1767. The number of houses may have been inadequate to shelter all the colonists in the first winter. Some family stories tell of their ancestors building partially underground huts, known as Zemlyanka, to live through the first winters until more housing could be built.

The original houses were known in Russian as Doma-pyatistenki, essentially a duplex with four exterior walls and one interior wall. The structures were designed to accommodate two households.

The original houses were known in Russian as Doma-pyatistenki, essentially a duplex with four exterior walls and one interior wall. The structures were designed to accommodate two households.

The houses were constructed of logs or lumber no thicker than 22 centimeters (8.7 inches). The structure was 6 by 10 meters (20 by 33 feet) with a chimney, floors, ceiling, five windows, four doors, two store rooms, and one oven. The height from floor to ceiling was at least 2.1 meters (6.9 feet). The doors and windows were equipped with latches. The roof had a small dormer, and a ladder to access the roof was placed on the front porch. The house was roofed with bast and topped with shingles held in place with wooden pegs.

Each household had its own courtyard. Farm buildings were roofed with bast and covered with reeds or thatch.

Each household had its own courtyard. Farm buildings were roofed with bast and covered with reeds or thatch.

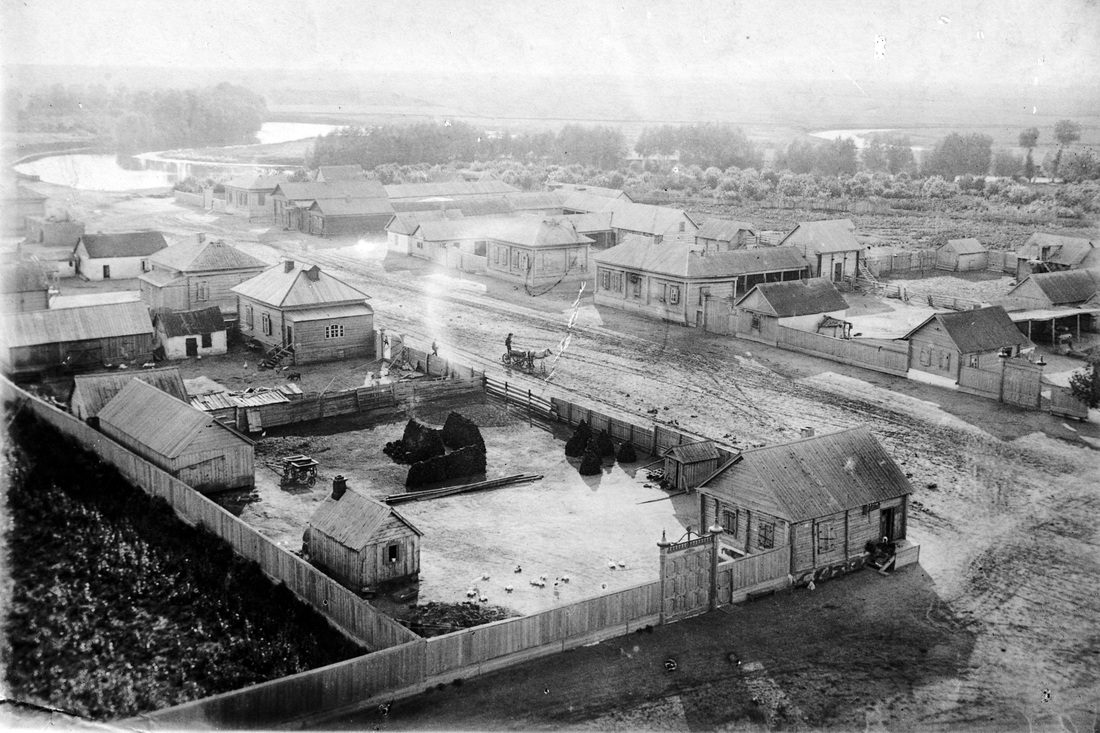

Unlike the farmland shared communally, the homesite was the exclusive domain of the owner. The homesite was a partially or entirely enclosed courtyard with a 1.8 to 2.4 meters (6 to 8 feet) tall fence. Sometimes, part of the enclosure was made of sapling trunks wattled with willow shoots or similar growth to save cost.

Inside the courtyard was the family home, barns, sheds, a granary (ambar), a root cellar, sometimes an ice cellar, possibly a well, and a summer kitchen. All baking and cooking took place in this kitchen during the hot summer months when no fires were built in the main house to keep it cool for sleeping. The summer kitchen was sometimes used year-round for baking, and it was always used for family washing. The summer kitchen was occasionally used as a summertime dining room and sleeping space.

The yard measured about 30 to 46 meters (100 to 150 feet) in width and ran about twice as long. The house was placed in a corner, forming part of the enclosure. The courtyard was divided by a fence into the Federhof (dialect for Vorderhof or front yard) and the Hinnerhof (dialect for Hinterhof or back yard). A solid gate, 2.5 to 3 meters (8 to 10 feet) wide, provided access for wagons to the front yard, and a smaller door allowed access for people only. A similar door and gate provided access to the backyard for wagons, farm equipment, and stock. The only access to the home was through the front courtyard, as typically, no doors opened directly onto the street.

Inside the courtyard was the family home, barns, sheds, a granary (ambar), a root cellar, sometimes an ice cellar, possibly a well, and a summer kitchen. All baking and cooking took place in this kitchen during the hot summer months when no fires were built in the main house to keep it cool for sleeping. The summer kitchen was sometimes used year-round for baking, and it was always used for family washing. The summer kitchen was occasionally used as a summertime dining room and sleeping space.

The yard measured about 30 to 46 meters (100 to 150 feet) in width and ran about twice as long. The house was placed in a corner, forming part of the enclosure. The courtyard was divided by a fence into the Federhof (dialect for Vorderhof or front yard) and the Hinnerhof (dialect for Hinterhof or back yard). A solid gate, 2.5 to 3 meters (8 to 10 feet) wide, provided access for wagons to the front yard, and a smaller door allowed access for people only. A similar door and gate provided access to the backyard for wagons, farm equipment, and stock. The only access to the home was through the front courtyard, as typically, no doors opened directly onto the street.

Typical Volga German homesite. A = front yard, B = back yard, 1 = house, 2 = vestibule, 3 = workshop, 4 = working kitchen, 5 = summer kitchen and bakehouse, 6 = gate and small door, 7 = pass through gate between yards, 8 = Cow and horse stall, 9 = roofed barn for wagons and carriages, 10 = sheep stables, 11 = pig stall, 12 = entry to the back yard, 13 = latrine, 14 = chicken pen, 15 = granary, 16 = main fence. Source: "Sachliche Volkskunde der Wolgadeutschen."

Log homes predominated in the early years but were gradually replaced by brick and dimension lumber homes. Hard-packed dirt floors gave way to oak planking, either painted or strewn with white sand. The sand absorbed mud tracked into the house from the yard and was swept out and replaced with a fresh supply when needed.

Most homes had thatched roofs made of select rye straw. These roofs were weathertight, durable, and provided insulation from the weather. Thatched roofs persisted into the last days of the German colonies, but in later years, tin and board roofs often replaced the thatch.

The metal and wood roofs were often painted red. Window frames were often painted red or green. The body of the house was generally whitewashed.

The metal and wood roofs were often painted red. Window frames were often painted red or green. The body of the house was generally whitewashed.

Homesites were arranged in orderly rows; each dwelling could have two to six rooms that accommodated two or more married couples and their children. Independent observers noted that homes were generally neat and orderly inside.

Related reading: Peter Miller - Norka and the Journey to America

Sources

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 78-80. Print.

Lonsinger, August, and Marion Hanke. Sachliche Volkskunde Der Wolgadeutschen. Remshalden: Bernhard Albert Greiner, 2004. Print.

"Protestantism in Russia." Christian Reflector & Christian Watchman [Boston] 17 Aug. 1848: Print.

"Register der deutschen Siedlungen Russlands."(Russian Language). Web. 13 Oct. 2017. <http://www.siedlung.rusdeutsch.ru/de/Siedlungsorte/39?c=2>.

Lonsinger, August, and Marion Hanke. Sachliche Volkskunde Der Wolgadeutschen. Remshalden: Bernhard Albert Greiner, 2004. Print.

"Protestantism in Russia." Christian Reflector & Christian Watchman [Boston] 17 Aug. 1848: Print.

"Register der deutschen Siedlungen Russlands."(Russian Language). Web. 13 Oct. 2017. <http://www.siedlung.rusdeutsch.ru/de/Siedlungsorte/39?c=2>.

Last updated January 16, 2024