Traditions > Funeral and Burial Traditions

Funeral and Burial Traditions

The Volga Germans practiced funeral and burial rites to remember and respect the life of a person who died. Death was always close at hand and considered a natural part of the cycle of our time on earth. The cemetery was familiar to people in the village, including children. Children were often told: "In every undertaking, consider that someday you will have to die."

When a death occurred, the church pastor was usually notified by the Hausvater (male head of the household). The pastor contacted the church deacon, who was responsible for the tolling of a bell to announce the death to the entire community.

Many churches in the Volga colonies, including Norka, had a large bell tower, which was important in communicating information to the community. One of the uses of the bell tower was to signal a death or a funeral service through the ringing of the bells. Upon hearing the bells signifying a death in the village, people bowed their heads and said: "Gott gebe ihm die ewige Ruh" (God grant him eternal rest).

When a death occurred, the church pastor was usually notified by the Hausvater (male head of the household). The pastor contacted the church deacon, who was responsible for the tolling of a bell to announce the death to the entire community.

Many churches in the Volga colonies, including Norka, had a large bell tower, which was important in communicating information to the community. One of the uses of the bell tower was to signal a death or a funeral service through the ringing of the bells. Upon hearing the bells signifying a death in the village, people bowed their heads and said: "Gott gebe ihm die ewige Ruh" (God grant him eternal rest).

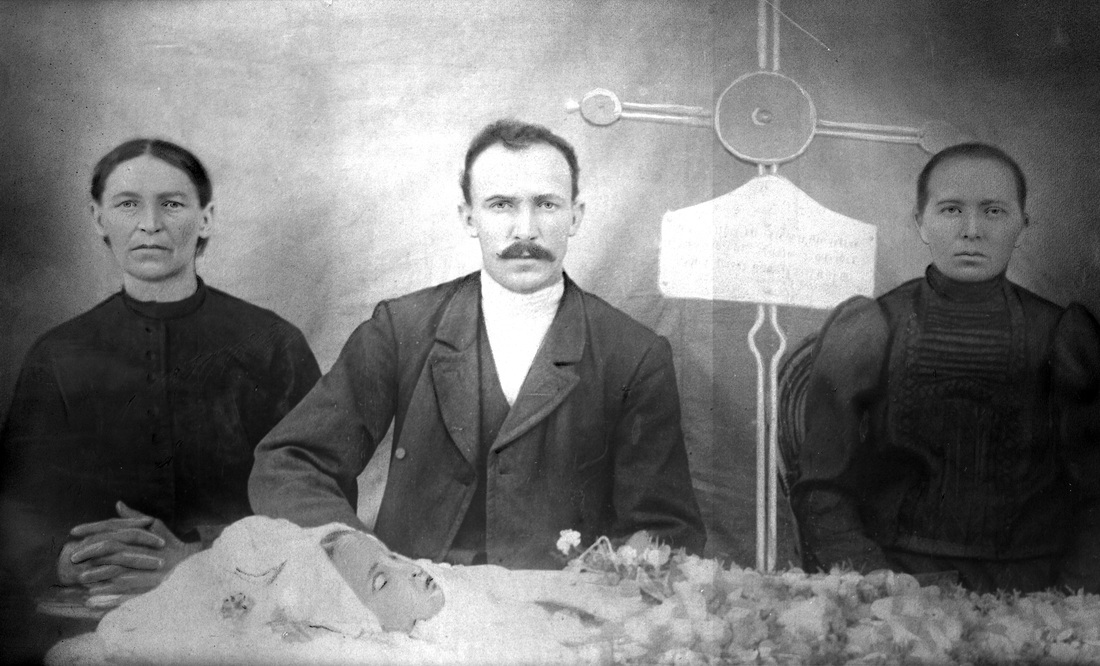

Photograph taken in Norka to commemorate the death of Maria Schreiber (circa 1909). Shown in the photo are her grandmother, Maria Catherine Schreiber (née Daubert) at left; father Heinrich Schreiber in the center; mother Catherine Schreiber (née Mai) at right. The deceased is covered in paper flowers. Photographs like this were commonly used to communicate the loss of a loved one to family and friends who lived overseas. This photo was sent by Heinrich Schreiber to his brother, Gottfried Schreiber, who was living in Portland, Oregon. Photograph courtesy of Steve Schreiber.

Inside the house, mirrors were covered with a black cloth, and the body of the deceased was laid upon a table where it was washed, dressed in their finest clothes, and prepared for burial. A village midwife performed these duties if the deceased was a woman and an elderly male prepared a male corpse. The corpse was not embalmed but was placed on a bier, usually a low bed of sand, that most households stored for use on their compacted dirt floors. The sand was heaped in a corner of the house, covered with a white sheet, and the deceased was placed on top. If the weather was warm, ice was packed around the body, and buckets of cold water were placed around the room to keep the temperature cool. It was customary to wait for three days between death and the funeral. The body was never left alone during this time. Elderly men usually performed the "watch nights." The family provided the night watchmen food and drink, including alcoholic beverages, to strengthen them during the long ordeal. There was no talking, singing, or praying during the watch, only silence.

The body of the deceased was measured by a Schreiner (carpenter) who began the construction of a coffin. Mill-cut lumber from the colony of Schilling was used to build coffins. The Gemeinde (village council) purchased the lumber, which was stored in a shed until needed. Anyone in the village was entitled to go there for material after a death in the family. Usually, someone in the deceased person's family would make the plain wooden coffin, but several carpenters were available for hire if needed. When the supply of lumber ran low, the Gemeinde asked the next person traveling to Schilling with a wagon to purchase more stock and bring it to Norka.

Coffins were typically designed as tapered boxes that were blunt on both ends, widened at the shoulder, and narrowed at the feet. The top of the coffin was wider than the base. Wood was scarce and expensive in the Volga region, and this practical design minimized the amount of lumber needed. Coffins were made specifically for the deceased. A coffin for an infant could be small enough to carry under a man's arm. If both a mother and infant died during childbirth (sadly, a frequent occurrence), the infant was usually placed next to the mother in the coffin. The bare wood was painted gray, light blue, or brown. The coffin's interior was filled halfway with wood shavings and then lined with fabric. A small pillow was made and covered in a matching fabric. It should be noted that a coffin is different than a casket.

When the coffin was completed, the deceased was removed from the bier and lowered inside with their hands placed as if in prayer. A paper rose, or poppy, was sometimes placed in the folded hands. The smell of freshly cut wood permeated the house.

The coffin was then placed on a bench or table in the house's largest room, and the sand used for the bier was swept away. Family and friends stopped by to pay their respects to the deceased and their family.

On the day of the funeral, family and friends met at the deceased's home to sing hymns and carry the coffin to the church where the service was held. The pastor of the church typically led the funeral services. The Schulmeister (schoolmaster) took his place if the pastor was unavailable.

Letters published in the German language newspaper Die Welt-Post during the famines of the 1920s make reference to the use of several Bible verses as a funeral text.

The body of the deceased was measured by a Schreiner (carpenter) who began the construction of a coffin. Mill-cut lumber from the colony of Schilling was used to build coffins. The Gemeinde (village council) purchased the lumber, which was stored in a shed until needed. Anyone in the village was entitled to go there for material after a death in the family. Usually, someone in the deceased person's family would make the plain wooden coffin, but several carpenters were available for hire if needed. When the supply of lumber ran low, the Gemeinde asked the next person traveling to Schilling with a wagon to purchase more stock and bring it to Norka.

Coffins were typically designed as tapered boxes that were blunt on both ends, widened at the shoulder, and narrowed at the feet. The top of the coffin was wider than the base. Wood was scarce and expensive in the Volga region, and this practical design minimized the amount of lumber needed. Coffins were made specifically for the deceased. A coffin for an infant could be small enough to carry under a man's arm. If both a mother and infant died during childbirth (sadly, a frequent occurrence), the infant was usually placed next to the mother in the coffin. The bare wood was painted gray, light blue, or brown. The coffin's interior was filled halfway with wood shavings and then lined with fabric. A small pillow was made and covered in a matching fabric. It should be noted that a coffin is different than a casket.

When the coffin was completed, the deceased was removed from the bier and lowered inside with their hands placed as if in prayer. A paper rose, or poppy, was sometimes placed in the folded hands. The smell of freshly cut wood permeated the house.

The coffin was then placed on a bench or table in the house's largest room, and the sand used for the bier was swept away. Family and friends stopped by to pay their respects to the deceased and their family.

On the day of the funeral, family and friends met at the deceased's home to sing hymns and carry the coffin to the church where the service was held. The pastor of the church typically led the funeral services. The Schulmeister (schoolmaster) took his place if the pastor was unavailable.

Letters published in the German language newspaper Die Welt-Post during the famines of the 1920s make reference to the use of several Bible verses as a funeral text.

Romans 8:18

"For I reckon that the sufferings of this present time [are] not worthy [to be compared] with the glory which shall be revealed in us."

Revelations 3:20

"Behold, I stand at the door, and knock: if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me."

Psalm 90:10

"The days of our years are threescore years and ten; and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years, yet is their strength labour and sorrow; for it is soon cut off, and we fly away."

Following the funeral service, a large procession of mourners made their way to the cemetery where the burial took place. The pastor and deacons led the singing of hymns from the Wolga Gesangbuch as they slowly walked. A young boy carrying a wooden cross, which would serve as the grave marker, walked ahead of the coffin. Four pallbearers carried the deceased on their shoulders. Although it was expected that family and close friends would be emotionally distraught, a certain amount of decorum was to be maintained.

The procession arrived at the cemetery where the grave had been prepared days earlier. The open grave was covered with a canvas tent. The tent was removed, and the pastor gave a final benediction to the deceased.

According to Dr. Timothy Kloberdanz, an authority on Volga German folklore, Protestant Volga Germans often painted the following words on the lids of homemade wooden coffins - Gute Nacht, ihr meine Freund (Good Night, My Friend/Relative). This phrase undoubtedly references the burial hymn Es ist genug! (It is Enough) - No. 703 in the Wolga Gesangbuch - which contains these very same words. As the coffin was slowly lowered into the grave, the mourners could see words on the coffin that were the same as those in the final farewell song that they were singing. This song, based on a poem by Anton Ulrich, was very popular in the German-speaking parts of Europe in the 1760s when the Volga Germans emigrated to Russia. The use of this poem faded in Germany, and it was rarely included in hymnals after the early 1900s, surviving primarily in the Wolga Gesangbuch.

The procession arrived at the cemetery where the grave had been prepared days earlier. The open grave was covered with a canvas tent. The tent was removed, and the pastor gave a final benediction to the deceased.

According to Dr. Timothy Kloberdanz, an authority on Volga German folklore, Protestant Volga Germans often painted the following words on the lids of homemade wooden coffins - Gute Nacht, ihr meine Freund (Good Night, My Friend/Relative). This phrase undoubtedly references the burial hymn Es ist genug! (It is Enough) - No. 703 in the Wolga Gesangbuch - which contains these very same words. As the coffin was slowly lowered into the grave, the mourners could see words on the coffin that were the same as those in the final farewell song that they were singing. This song, based on a poem by Anton Ulrich, was very popular in the German-speaking parts of Europe in the 1760s when the Volga Germans emigrated to Russia. The use of this poem faded in Germany, and it was rarely included in hymnals after the early 1900s, surviving primarily in the Wolga Gesangbuch.

Dr. Kloberdanz notes that when Protestant Volga Germans in the United States or Canada are asked what German hymns traditionally were sung at the graveside, there are two common responses: Wo findet die Seele die Heimat, die Ruh (Where Does the Soul Find Its Home, Its Rest) and Lasst mich gehen (Let Me Go). Reuben Miller, a descendant of Norka ancestry from Stony Plain, Alberta, Canada, confirms that these two songs were always sung at the funerals of people from Norka and their descendants. Reuben recalls that Wo findet die Seele die Heimat, die Ruh was sung at the funeral service, and Lasst mich gehen was sung at the graveside. An entire section of the Wolga Gesangbuch, comprised of 20 hymns, is devoted to Vorbereitung zum Tode und Verlangen, bei Jesu Christo zu sein (Preparing for death and the desire to be with Jesus Christ).

Some Volga Germans traditionally sang the funeral hymn Das Schicksal wird keinen verschonen (The fate that will spare no one) at the graveside as the coffin slowly was lowered into the ground. The lyrics below by G. Schneidmiller are from the songbook Der köstliche Schatz.

1. Das Schicksal tut keinen verschonen, / der Tod, der folgt selber auf Thronen; / Eitel, eitel bricht zeitliches Glück, / Alles, alles fällt wieder zurück.

2. Der Leib, von der Erde genommen, / geht hin, wo er her ist gekommen; / Reichtum im Grabe vergeht, / nur Tugend einzig besteht.

3. Der Leib in der Erde vermodert, / bis dass ihn der Herr wird auffordern. / Heut ist die Reihe an mir, morgen ist sie schon an dir.

1. Das Schicksal tut keinen verschonen, / der Tod, der folgt selber auf Thronen; / Eitel, eitel bricht zeitliches Glück, / Alles, alles fällt wieder zurück.

2. Der Leib, von der Erde genommen, / geht hin, wo er her ist gekommen; / Reichtum im Grabe vergeht, / nur Tugend einzig besteht.

3. Der Leib in der Erde vermodert, / bis dass ihn der Herr wird auffordern. / Heut ist die Reihe an mir, morgen ist sie schon an dir.

|

|

|

After the hymns were sung, the pallbearers shoveled dirt onto the coffin, closing the grave. Earth was heaped up on the grave until a low mound was formed, and the wooden cross was placed at the head of the grave. The crosses were usually painted. White was the color used for small children. Darker colors (gray, brown, black) were used for older adults. The deceased's name, birthdate, and date of death were burned into the cross and painted in a contrasting color. There was little difference between the funeral rites for the rich and poor, although the wealthier might have a carved headstone rather than a simple wooden cross.

Today, almost all of the older markers (pre-1941) in the Norka cemetery have been removed and destroyed. Superstition has prevented the current residents from building on the burial sites. One toppled stone grave marker for a wealthy Sinner family has been found buried in the overgrown brush.

Today, almost all of the older markers (pre-1941) in the Norka cemetery have been removed and destroyed. Superstition has prevented the current residents from building on the burial sites. One toppled stone grave marker for a wealthy Sinner family has been found buried in the overgrown brush.

Following the closure of the grave, it was adorned with natural or paper flowers.

Plots were typically arranged in chronological order. When one row was finished, another was begun. Most burial sites were the same, except for those that committed suicide. Their graves were located outside the main cemetery enclosure.

After the burial service, the pallbearers returned to the home of the deceased for a meal with the bereaved family. The meal was prepared by women in the village. A popular dish served at these meals was traditional Volga German chicken noodle soup made with homemade egg noodles, de-boned stewed chicken, and chopped onions cooked together in a chicken broth. Cubed potatoes could be added as an option. This dish was also popular at wedding dinners.

Rain after the burial was considered a good omen. Windy days meant a fight between good and evil for the soul of the deceased.

The first Kirchhof (cemetery) used by the original colonists was said to exist in a sandy area along First Street that later became the Unterdorf or the lower part of the colony.

The second Friedhof (cemetery) was near the Ella Born Brücke (the bridge over the Ella Born).

Plots were typically arranged in chronological order. When one row was finished, another was begun. Most burial sites were the same, except for those that committed suicide. Their graves were located outside the main cemetery enclosure.

After the burial service, the pallbearers returned to the home of the deceased for a meal with the bereaved family. The meal was prepared by women in the village. A popular dish served at these meals was traditional Volga German chicken noodle soup made with homemade egg noodles, de-boned stewed chicken, and chopped onions cooked together in a chicken broth. Cubed potatoes could be added as an option. This dish was also popular at wedding dinners.

Rain after the burial was considered a good omen. Windy days meant a fight between good and evil for the soul of the deceased.

The first Kirchhof (cemetery) used by the original colonists was said to exist in a sandy area along First Street that later became the Unterdorf or the lower part of the colony.

The second Friedhof (cemetery) was near the Ella Born Brücke (the bridge over the Ella Born).

The third cemetery was in the fields south of the old church in the Mitteldorf (middle section of the village). The fourth and fifth cemeteries were established during the early 1920s to accommodate all those who died during the severe famine from 1921 to 1924. The fourth cemetery was established in 1921, and the fifth was full by 1926. At least one more cemetery was developed to accommodate those who died before the deportation in 1941.

In 1853, a Gottesacker (a small cemetery - literally "God's Acre" or "God's Garden") was established to the west of and adjacent to the two existing Mitteldorf cemeteries. This was a separate cemetery for the pastors of the church.

Edith Müthel, daughter of Rev. Emil Pfeiffer, wrote about the cemetery in Norka in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In 1853, a Gottesacker (a small cemetery - literally "God's Acre" or "God's Garden") was established to the west of and adjacent to the two existing Mitteldorf cemeteries. This was a separate cemetery for the pastors of the church.

Edith Müthel, daughter of Rev. Emil Pfeiffer, wrote about the cemetery in Norka in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

"The village consists of ten lines of houses and five very long streets on which part of the houses are made from clay, brick or logs, covered with boards or iron sheets… the houses border an old cemetery. The paths in the cemetery were well-groomed. It was planted with lilacs and roses, a white acacia, birches, aspens and elms - a botanical garden. There I could hide with a book and quietly read."

Today, the old German cemetery lies nearly empty of gravestones or wooden markers. A new cemetery for the residents who were relocated to Norka after the deportation of the Volga Germans in 1941 is located adjacent to the older cemetery. A few graves can be found for Germans who returned to Norka after the deportation, although they were forbidden by law to do so. These people wanted, more than anything, to live and die in the place they called home.

Sources

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka," Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Vol. 8, No. 2, Summer 1985.

Die Welt Post, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Kloberdanz, Timothy J., and Rosalinda Kloberdanz. Thunder on the Steppe: Volga German Folklife in a Changing Russia. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1993. 260. Print.

Kloberdanz, Timothy J., "Funerary Beliefs and Customs of the Germans from Russia," Work Paper No. 20 of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Spring 1976. 65.

Krieger, Joanne. "A Norka Funeral". Norka Newsletter. Summer 1998. Page 12.

Olson, Marie Miller, and Anna Miller Reisbick. Norka, a German Village in Russia. Lincoln, Nebraska: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1986. 9. Print.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown.

Die Welt Post, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Kloberdanz, Timothy J., and Rosalinda Kloberdanz. Thunder on the Steppe: Volga German Folklife in a Changing Russia. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1993. 260. Print.

Kloberdanz, Timothy J., "Funerary Beliefs and Customs of the Germans from Russia," Work Paper No. 20 of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Spring 1976. 65.

Krieger, Joanne. "A Norka Funeral". Norka Newsletter. Summer 1998. Page 12.

Olson, Marie Miller, and Anna Miller Reisbick. Norka, a German Village in Russia. Lincoln, Nebraska: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1986. 9. Print.

Preisendorf, Johannes. "Auszüge aus der Chronik der Kolonie Norka and der Wolga." Der Kirchenbote. Date Unknown.

Last updated November 28, 2023