History > Repression 1941 - 1956

Repression 1941 - 1956

“It is unthinkable in the twentieth century to fail to distinguish between what constitutes an abominable atrocity that must be prosecuted and what constitutes that "past" which "ought not to be stirred up.”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956

On September 7, 1941, shortly after the deportation of the entire Volga German population to Siberia and Central Asia, the Autonomous Volga German Republic was abolished. By early 1942, German place names in the Volga region were changed to Russian names. Although Norka did not have a German name (it is the Russian word for mink), the colony's name was nevertheless changed to Nekrasovo.

The Soviet secret police (NKVD) created a Special Settlements Department to handle the influx of German deportees to Siberia and Central Asia. At the time, the Gulag system was not equipped to handle such a large influx of people immediately.

The so-called Special Settlements were typically located within existing Russian villages. Germans were initially placed in the already inhabited homes of Russian and Kazakh kolkhoz workers, abandoned buildings needing repair, and even earth huts. The Special Settlements also experienced severe shortages of food, medicine, and winter clothing. As a result, large numbers of them perished from malnutrition, disease, and exposure. The reaction from their Kazakh and Russian "hosts" was mixed. Some felt sympathy for the deported Germans, and others felt animosity towards the "fascists." The Germans were not allowed to leave the Special Settlement areas and had to report regularly to the Soviet authorities.

The Soviet secret police (NKVD) created a Special Settlements Department to handle the influx of German deportees to Siberia and Central Asia. At the time, the Gulag system was not equipped to handle such a large influx of people immediately.

The so-called Special Settlements were typically located within existing Russian villages. Germans were initially placed in the already inhabited homes of Russian and Kazakh kolkhoz workers, abandoned buildings needing repair, and even earth huts. The Special Settlements also experienced severe shortages of food, medicine, and winter clothing. As a result, large numbers of them perished from malnutrition, disease, and exposure. The reaction from their Kazakh and Russian "hosts" was mixed. Some felt sympathy for the deported Germans, and others felt animosity towards the "fascists." The Germans were not allowed to leave the Special Settlement areas and had to report regularly to the Soviet authorities.

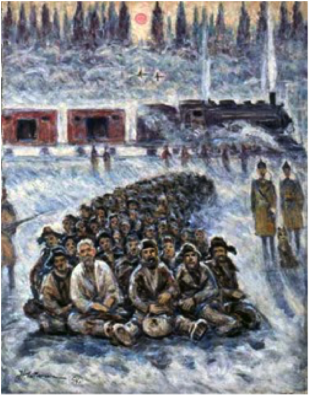

Within months of the deportation, the Soviets issued an order on January 10, 1942, that subjected the German-Russians to conscription in the Trudarmee (Labor army). On February 14, 1942, the government required that all deported German males (ages 17 to 50) be separated from their families and sent from the Special Settlements to the NKVD's Trudarmee camps, where they primarily were forced to work in construction or harvesting timber in the Ural Mountains. Some were assigned to work building railroads.

On October 7, 1942, the Soviets ordered that the deported German women from ages 16 to 45 also be sent to labor camps. This same order expanded the age range for conscripting men to include all those from 15 to 55 years of age. The only exceptions were men who were physically unable to work and women who were pregnant or those who had children up to three years of age. With so many of the adults sent to the labor camps, many of the Germans remaining in Kazakhstan and Siberia were children without any adult relatives to look after them.

In the labor camps, the people were formed into units of 1,500 to 2,000 people. The units were again divided into labor columns of 250 to 500 people and teams of 35 to 100 people assigned to the same barracks. Each individual worked under a regime of forced labor, often with inadequate housing and food. Harsh climatic conditions and overwork led to a high mortality rate, but the dead were not recorded, so the exact number of victims is unknown. It is clear that within the deported German population, deaths exceeded births until 1948.

One of the inmates at Usollag provided these memories:

On October 7, 1942, the Soviets ordered that the deported German women from ages 16 to 45 also be sent to labor camps. This same order expanded the age range for conscripting men to include all those from 15 to 55 years of age. The only exceptions were men who were physically unable to work and women who were pregnant or those who had children up to three years of age. With so many of the adults sent to the labor camps, many of the Germans remaining in Kazakhstan and Siberia were children without any adult relatives to look after them.

In the labor camps, the people were formed into units of 1,500 to 2,000 people. The units were again divided into labor columns of 250 to 500 people and teams of 35 to 100 people assigned to the same barracks. Each individual worked under a regime of forced labor, often with inadequate housing and food. Harsh climatic conditions and overwork led to a high mortality rate, but the dead were not recorded, so the exact number of victims is unknown. It is clear that within the deported German population, deaths exceeded births until 1948.

One of the inmates at Usollag provided these memories:

“There were more then a hundred of us in the barrack. The best places on the wooden bunks where taken by thieves. To the right of the door a few bunks were occupied by syphilitics. There was only one water tank, and a common aluminum mug was chained to it. “

“It was a very cold winter (-40 to -49 F), we had no appropriate clothing. A prisoner should work cutting trees in the forest 12–16 hours a day to earn his bread ration (1.5 lb). People were dying; the corpses were taken away to the cemetery after the beep at 12:00 midnight. “

“I remember a case when 29 people died in one day in the barracks… When we were going to work, we were counted, and the same amount of people was expected to come back. Because of the scarcity of food, we had the disease – “chicken blindness:” people couldn’t see at night. Winter, cold … Go back, search for the missing men, until you find them. Many of them were found dead… Among inmates there were a lot of military wives and ethnic German women with little children, imprisoned without a trial. They, too, were forced to work. There was a nursery in the camp. When the baby turned 7 years old, it was taken from the camp and sent to an orphanage.”

Stalin's regime conscripted hundreds of thousands of civilian German "Special Settlers" into the labor army. In 1942 alone, over 120,000 German "Special Settlers" were sent to work in lumber camps, industrial construction projects, fishing operations, mines, and railroad buildings. By 1943, the Soviet government had mobilized over 316,000 ethnic Germans into the labor army to perform forced labor. These labor battalions worked under NKVD discipline. The NKVD severely punished escape attempts and refusals to work, often through execution. The labor camps were not significantly different from the Gulags; they lived behind barbed wire patrolled by guard dogs, were watched from observation platforms, their presence was regularly verified, were provided a minimal amount of food twice a day, and received one day of rest for every ten days of work. Those who refused to work were severely punished or executed. As a result of the inhumane conditions in the labor army, over 60,000, or nearly one-fifth of those conscripted, perished during and soon after the war.

Soviet records show that at least 213 people from Norka and Neu-Norka were sent to TagiLag (near the city of Nizhny Tagil located in the Sverdlovsk Oblast), and 198 men are listed at Usollag (located in Solikamsk, Perm Krai - near the Ural mountains).

In this early 1950's photograph, Alexander Konrad Schreiber, a native of Norka, is shown seated on the right. Alexander's wife, Claudia is seated in the center and a friend of Alexander's from Norka, Egor Schlidt, is seated to the left. At this time, life in the camps began to improve in comparison with the terrible years at the beginning of war. This photo, taken at a camp in the Ural Mountains, was provided by Alexander Schreiber, son of Alexander Konrad Schreiber.

In early 1946, with the war over, the labor camps were abolished. However, the conscripted workers were to remain attached to their assigned companies. They could move out of their camp but had to stay in the area. After years of separation, they could write to their family members.

On November 26, 1948, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a "Top Secret" decree that placed criminal responsibility on those who attempted to leave the places of compulsory settlement. This decree directly and unambiguously stipulated that the Germans, like all other nations that were sent to special settlements during the war, had been relocated there "forever," without the right to return to their former places of residence before the deportation. The decree repeated the People's Commissars of the USSR's decision on January 8, 1945, that those offenders attempting an unauthorized exit (escape) from places of compulsory settlement were subject to criminal liability. The decree of November 26th went further in stating that special settlers who violated the directive to remain in the special settlements were subject to the draconian punishment of 20 years of hard labor.

Perhaps the most significant impact on the Volga Germans was the loss of their churches, schools, newspapers, and language. The traditions and culture of this ethnic group were significantly damaged by the deportation.

The deportation of the Volga Germans was a form of genocide, murder not only of individuals but of the ethnic group's sense of itself. This form of ethnic cleansing had been employed by ruthless dictators for millennia and was used by Stalin and his henchmen to repress numerous ethnic groups in the Soviet Union.

With the death of Stalin in 1953, the deportation policy was reviewed and belatedly renounced. In March 1955, ethnic Germans were again allowed to have passports. On December 13, 1955, the Soviet regime released the German-Russians from the special settlements. However, the same decrees that eliminated the special settlement restrictions also prohibited the German-Russians from returning to their homelands or receiving compensation for confiscated property. Soviet officials claimed that all of them had “taken root” in their new areas of residence.

An English translation by J. Otto Pohl of the 1955 decree is presented below:

On November 26, 1948, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a "Top Secret" decree that placed criminal responsibility on those who attempted to leave the places of compulsory settlement. This decree directly and unambiguously stipulated that the Germans, like all other nations that were sent to special settlements during the war, had been relocated there "forever," without the right to return to their former places of residence before the deportation. The decree repeated the People's Commissars of the USSR's decision on January 8, 1945, that those offenders attempting an unauthorized exit (escape) from places of compulsory settlement were subject to criminal liability. The decree of November 26th went further in stating that special settlers who violated the directive to remain in the special settlements were subject to the draconian punishment of 20 years of hard labor.

Perhaps the most significant impact on the Volga Germans was the loss of their churches, schools, newspapers, and language. The traditions and culture of this ethnic group were significantly damaged by the deportation.

The deportation of the Volga Germans was a form of genocide, murder not only of individuals but of the ethnic group's sense of itself. This form of ethnic cleansing had been employed by ruthless dictators for millennia and was used by Stalin and his henchmen to repress numerous ethnic groups in the Soviet Union.

With the death of Stalin in 1953, the deportation policy was reviewed and belatedly renounced. In March 1955, ethnic Germans were again allowed to have passports. On December 13, 1955, the Soviet regime released the German-Russians from the special settlements. However, the same decrees that eliminated the special settlement restrictions also prohibited the German-Russians from returning to their homelands or receiving compensation for confiscated property. Soviet officials claimed that all of them had “taken root” in their new areas of residence.

An English translation by J. Otto Pohl of the 1955 decree is presented below:

On Lifting the Restrictions on the Legal Status of Germans and Members of their Families, found in special settlements.

Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR from 13 December 1955

Having learned that the existing restrictions on the legal status of special settler-Germans and members of their families, exiled to various regions of the country, are no longer deemed necessary, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet resolves:

1. To lift from the count of special settlement and free from administrative surveillance of the organs of the MVD Germans and members of their families, exiled as special settlers in the period of the Great Fatherland War, and also Germans - citizens of the USSR, that after repatriation from Germany were moved to special settlements.

2. Establishes, that the lifting from Germans of the restrictions of special settlement will not lead to the return of property confiscated during exile, and that they do not have the right to return to the places from which they were exiled.

Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR

K. Voroshilov

Secretary of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR

N. Pegov

In February 1956, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev condemned the deportations as violating Leninist principles.

In August 1964, rehabilitation decrees were approved by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet for the Russian Germans, but they were again prohibited from returning to their homelands.

Restrictions limiting where the ethnic Germans could live were lifted on November 3, 1972, and some chose to return to their homes at this time, although this was still officially discouraged. The former German colonies had been populated by other peoples for over 30 years, and the new residents did not want the Germans to return.

No longer in their ethnic conclaves, many Volga Germans intermarried with other ethnic groups living in the areas where they had been deported or served in labor camps.

One last attempt was made in the 1980s to regain and revitalize their Volga German homeland.

In August 1990, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev signed a decree "On the restoration of the rights of victims of political repression 1920-1950." Unfortunately, much of what was promised to repressed peoples, including the German-Russians, was never implemented.

It wasn't until October 18, 1991 (after the collapse of the Soviet Union) that the Russian government belatedly issued a decree rehabilitating all the victims of political repression.

In 2015, ethnic Germans living in the Russian Federation continued working to perpetuate the memory of victims of political repression. Specifically, they were seeking free access to archival material and memorial sites, the preservation and promotion of the cultural values of all peoples of the Russian Federation who were subjected to repression, and the creation of educational and outreach programs related to political repression.

In August 1964, rehabilitation decrees were approved by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet for the Russian Germans, but they were again prohibited from returning to their homelands.

Restrictions limiting where the ethnic Germans could live were lifted on November 3, 1972, and some chose to return to their homes at this time, although this was still officially discouraged. The former German colonies had been populated by other peoples for over 30 years, and the new residents did not want the Germans to return.

No longer in their ethnic conclaves, many Volga Germans intermarried with other ethnic groups living in the areas where they had been deported or served in labor camps.

One last attempt was made in the 1980s to regain and revitalize their Volga German homeland.

In August 1990, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev signed a decree "On the restoration of the rights of victims of political repression 1920-1950." Unfortunately, much of what was promised to repressed peoples, including the German-Russians, was never implemented.

It wasn't until October 18, 1991 (after the collapse of the Soviet Union) that the Russian government belatedly issued a decree rehabilitating all the victims of political repression.

In 2015, ethnic Germans living in the Russian Federation continued working to perpetuate the memory of victims of political repression. Specifically, they were seeking free access to archival material and memorial sites, the preservation and promotion of the cultural values of all peoples of the Russian Federation who were subjected to repression, and the creation of educational and outreach programs related to political repression.

Kazakhstan launched a social advertising program in May 2015 under the slogan "One country. One people. One destiny." The project's first series is dedicated to the deportation of the Volga Germans. The video shows the Kazakhs as very hospitable people. In contrast, the real villains are the NKVD, who implemented the deportation order and later forcibly mobilized adults into the labor army and weaned children from their parents. The video below was an attempt to keep the remaining Germans in Kazakhstan from leaving the country.

Learn more about people from Norka who were interred in Soviet Gulags.

Search the Russian Gulag database here.

Search the Russian Gulag database here.

Sources

"Book of Memory of Soviet Germans - Prisoners of Tagillag! (Russian Language). Книга памяти советских немцев - узников Тагиллага!" Книга памяти советских немцев - узников Тагиллаг! Гордое терпенье. Web. Apr. 2015. <http://www.tagillag.rusdeutsch.ru/>.

Chebikina, T. "Deportation of the German Population from the European Part of the USSR to Western Siberia (1941-1945). (Russian Language)." Мемориал - Главная страница. Web. 16 Mar. 2016. <http://old.memo.ru/history/nem/Chapter14.htm>.

Conquest, Robert. The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities. London: Macmillan, 1970. Print.

Grib, E. A. Gedenkbuch : kniga pami︠a︡ti nemt︠s︡ev-trudarmeĭt︠s︡ev Usolʹlaga NKVD-MVD SSSR, 1942-1947 (A Memorial Book of the Germans in Labor Army Usollag NKVD/MVD the USSR 1942-1947). Ed. V. F. Dizendorf: Public Academy of Sciences of the Russian Germans, 2006. Print.

Pohl, J. Otto. "The Deportation and Destruction of the German Minority in the USSR." JOP (2004): Print.

Pohl, J. Otto. "Ethnic Erasure: The Role of Border Changes in Soviet Ethnic Cleansing and Return Migration."

Pohl, J. Otto. "Let Us Just Call it "Anti-German". Blog - 20th Century Musings in the 21st Century, 25 Jul 2021.

Sinner, Samuel D. The Open Wound: The Genocide of German Ethnic Minorities in Russia and the Soviet Union, 1915-1949 and beyond. Fargo, ND: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State University Libraries, 2000. Print.

Chebikina, T. "Deportation of the German Population from the European Part of the USSR to Western Siberia (1941-1945). (Russian Language)." Мемориал - Главная страница. Web. 16 Mar. 2016. <http://old.memo.ru/history/nem/Chapter14.htm>.

Conquest, Robert. The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities. London: Macmillan, 1970. Print.

Grib, E. A. Gedenkbuch : kniga pami︠a︡ti nemt︠s︡ev-trudarmeĭt︠s︡ev Usolʹlaga NKVD-MVD SSSR, 1942-1947 (A Memorial Book of the Germans in Labor Army Usollag NKVD/MVD the USSR 1942-1947). Ed. V. F. Dizendorf: Public Academy of Sciences of the Russian Germans, 2006. Print.

Pohl, J. Otto. "The Deportation and Destruction of the German Minority in the USSR." JOP (2004): Print.

Pohl, J. Otto. "Ethnic Erasure: The Role of Border Changes in Soviet Ethnic Cleansing and Return Migration."

Pohl, J. Otto. "Let Us Just Call it "Anti-German". Blog - 20th Century Musings in the 21st Century, 25 Jul 2021.

Sinner, Samuel D. The Open Wound: The Genocide of German Ethnic Minorities in Russia and the Soviet Union, 1915-1949 and beyond. Fargo, ND: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State University Libraries, 2000. Print.

Last updated December 7, 2023