Religion > Church Practices

Church Practices

Catherine's Manifesto of 1763 promised freedom of religious practice to the colonists.

We grant to all foreigners coming into Our Empire the free and unrestricted practice of their religion according to the precepts and usage of their Church.

Most people who founded Norka in 1767 were practitioners of the Reformed faith. Before migrating to Russia in 1766, most had lived in the County of Ysenburg (Isenburg), ruled by the pietistic noble house of Isenburg-Büdingen. There was a small minority of people who were Lutherans and a handful of Catholics. While the Reformed and Lutherans were Protestants, notable differences in religious beliefs and practices sometimes created friction.

In the early years, separate church services were held for the Lutheran and Reformed faith families. Both services were performed by a Lutheran or Reformed pastor in the colony. After years of socialization and intermarriage, religious differences were set aside, and everyone worshipped together.

According to Joseph Schnurr, by 1906, the parish of Norka (including the colonies of Huck and Neu-Messer) had 23,179 members. Only 385 were Lutherans, and the remaining 22,794 were of the Reformed faith.

In the Volga German colonies, Sundays were kept sacred and strictly observed as a day of rest. The people loved cleanliness (order), and most Volga Germans swept their houses and washed their vestibule floors daily. There was a thorough house cleaning on Saturdays and before holidays. Often, the men had to leave the house because the “cleaning devil” took possession of the women, who were called the Lappenvolk (dust rag folk). On Saturdays, not only the house but the yard and the street in front of the house were swept very thoroughly. Fresh underwear and Sunday clothing were readied, and boots and shoes were polished. Sundays had a special significance. The house, yard, and people needed to be clean and nice-looking. Anything that could perhaps damage or restrain the holiday spirit on Sunday mornings was eliminated.

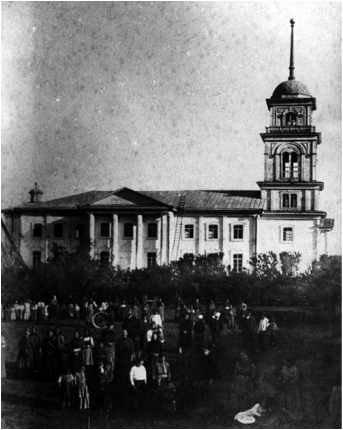

On Sunday morning, large crowds filled the streets, making their way to attend church after hearing the first tolling of the bell one hour before the service was to begin. Every person carried Die Heilige Schrift (the Bible or Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments) and the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga hymnal). Men held the books under their arms and women in their hands. In the summertime, the women also put pungent herbs (such as Riechkraut) in their hymnals to refresh themselves. In wintertime, they put a white handkerchief in their hymnal. Many people started their pilgrimage to the church between the first and third tolling of the bells. After the third tolling, the streets were empty. A Sunday stroll was considered bad manners except for a walk to church.

In the early years, separate church services were held for the Lutheran and Reformed faith families. Both services were performed by a Lutheran or Reformed pastor in the colony. After years of socialization and intermarriage, religious differences were set aside, and everyone worshipped together.

According to Joseph Schnurr, by 1906, the parish of Norka (including the colonies of Huck and Neu-Messer) had 23,179 members. Only 385 were Lutherans, and the remaining 22,794 were of the Reformed faith.

In the Volga German colonies, Sundays were kept sacred and strictly observed as a day of rest. The people loved cleanliness (order), and most Volga Germans swept their houses and washed their vestibule floors daily. There was a thorough house cleaning on Saturdays and before holidays. Often, the men had to leave the house because the “cleaning devil” took possession of the women, who were called the Lappenvolk (dust rag folk). On Saturdays, not only the house but the yard and the street in front of the house were swept very thoroughly. Fresh underwear and Sunday clothing were readied, and boots and shoes were polished. Sundays had a special significance. The house, yard, and people needed to be clean and nice-looking. Anything that could perhaps damage or restrain the holiday spirit on Sunday mornings was eliminated.

On Sunday morning, large crowds filled the streets, making their way to attend church after hearing the first tolling of the bell one hour before the service was to begin. Every person carried Die Heilige Schrift (the Bible or Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments) and the Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga hymnal). Men held the books under their arms and women in their hands. In the summertime, the women also put pungent herbs (such as Riechkraut) in their hymnals to refresh themselves. In wintertime, they put a white handkerchief in their hymnal. Many people started their pilgrimage to the church between the first and third tolling of the bells. After the third tolling, the streets were empty. A Sunday stroll was considered bad manners except for a walk to church.

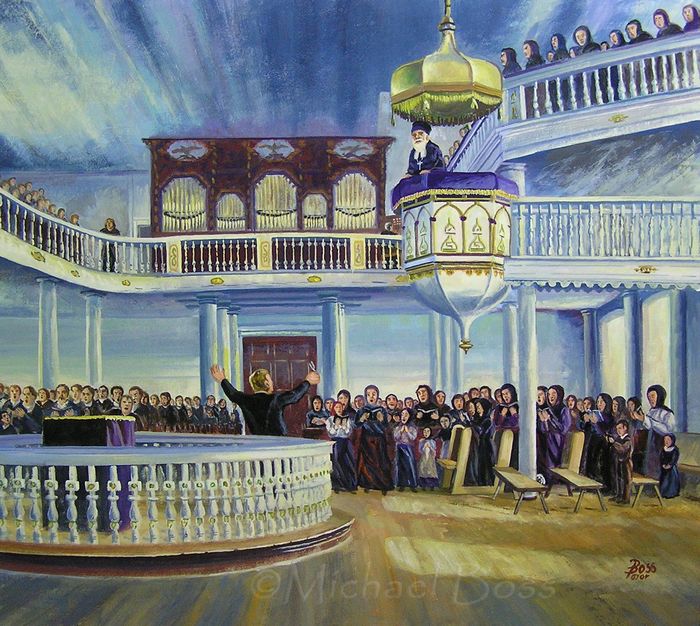

After arriving at the churchyard and chatting with friends and family, the worshippers would pass through a spacious narthex (entry) where all the stairways to the balconies were located. They entered the church's nave (main body) from the narthex. The altar was located straight ahead of the narthex, and the circular chancel (the part of the church containing the altar and the chairs for the clergy) was somewhat raised. The pulpit in Norka was suspended to the side of the altar. Behind the altar is a wall richly decorated in gold and other colors. To the right and left of the chancel, two doors lead to the sacristy (the room where the pastor prepares for worship.) A row of high, thick columns bear the weight of the church balcony. The organ and the choir were on the balcony above the church narthex.

The church was packed on Sunday, and usually, every seat was taken. The only time this was not the case was in midsummer when people were out working on the steppe. In the German tradition, the males were seated on the right side and the females on the left. Both men and women were seated according to their year of birth. Members of the church council, village dignitaries, and their families were seated at the front on the left and right sides of the chancel, where they sat on pews covered with red cloth. The congregation's venerable older ladies and older gentlemen were also seated in front. Seating was arranged according to married couples' birth years, right down to the single females seated at the back of the church. Young single men sat upstairs in the church balcony. Often, young married men also sat there. This arrangement was so carefully adhered to that in some churches, there were even small signboards with the number of those born in a particular year. These were attached to the columns in front of the pews, indicating who had permission to be seated in those pews.

Everyone sat quietly and meditated in preparation for the service, which typically began at 10:00 a.m. Then, the schoolmaster’s voice was heard from the organ loft. He announced to the congregation that: “To start our worship service, we will sing the hymn listed as number . . . ” or “To begin our service may the Christian congregation enjoy singing the hymn listed under number . . . and if a verse of the hymn of the day was sung after the sermon, many elderly schoolmasters announced this by saying: “We will sing verse . . . from the hymn which we have begun to sing.” As a rule, hymn boards were not used.

At the signal from the schoolmaster, hundreds or even thousands of voices filled the church. Pastor Seib said the singing was so impressive that it "penetrated to the very marrow." Volga Germans liked to sing and sing loud. The ruddy complexions of the church attendees were witness to the fact that singing was an essential part of worship. Parishioners were serious about singing. It is said that people braced their legs on the back of pews to be able to sing with all their might.

In general, congregational singing was very satisfactory. However, Pastor Seib reported that "the bad habit" of singing hymns too slowly (dragging) and women singing tenor was still practiced in some places.

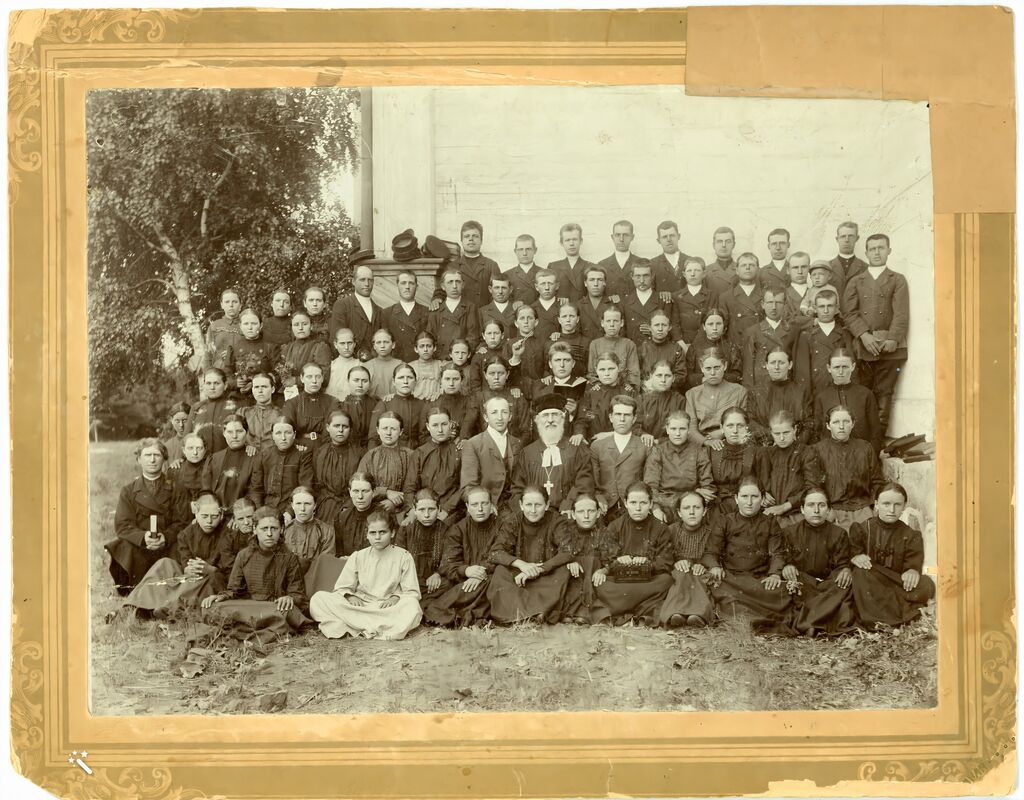

The second floor held the choir and the great pipe organ. The choir consisted of unmarried men and women who would sing two or three selections aside from the congregational singing. The choirmaster was known in German as the Chorleiter. The job of the Chorleiter was to give the choir or congregation the musical pitch by striking a tuning fork against the metal music stand and then raising it with all to listen to carefully and hum the tone in their heads, thus giving the musical pitch for all the basses, tenors, altos and sopranos to be in harmony (a four-part harmony). Then, the organ began to play, and either the choir and/or the congregation chimed in with the singing of that specific hymn. The role of the Chorleiter was very significant and necessary. His job was to lead the singing but also to bring the singing together in a harmonious tonal quality. The choirs sang for festivals and every Sunday, except in the summer when the farmers had no time for anything except farming.

Church services lasted one hour and forty-five minutes, and the sermon was delivered from the suspended pulpit. The congregation stood from the beginning to the end of the liturgy. If “Jesus Christ” was mentioned, the women bent a knee. During the sermon, the audience would nod approvingly if something in the sermon pleased them, and they repeated the mentioned Bible verses aloud. This showed how attentively the audience listened to the sermon and how well the people memorized many Bible verses.

Pastor Seib wrote, "It is truly a joy to preach in the colonies along the Volga!"

The church was packed on Sunday, and usually, every seat was taken. The only time this was not the case was in midsummer when people were out working on the steppe. In the German tradition, the males were seated on the right side and the females on the left. Both men and women were seated according to their year of birth. Members of the church council, village dignitaries, and their families were seated at the front on the left and right sides of the chancel, where they sat on pews covered with red cloth. The congregation's venerable older ladies and older gentlemen were also seated in front. Seating was arranged according to married couples' birth years, right down to the single females seated at the back of the church. Young single men sat upstairs in the church balcony. Often, young married men also sat there. This arrangement was so carefully adhered to that in some churches, there were even small signboards with the number of those born in a particular year. These were attached to the columns in front of the pews, indicating who had permission to be seated in those pews.

Everyone sat quietly and meditated in preparation for the service, which typically began at 10:00 a.m. Then, the schoolmaster’s voice was heard from the organ loft. He announced to the congregation that: “To start our worship service, we will sing the hymn listed as number . . . ” or “To begin our service may the Christian congregation enjoy singing the hymn listed under number . . . and if a verse of the hymn of the day was sung after the sermon, many elderly schoolmasters announced this by saying: “We will sing verse . . . from the hymn which we have begun to sing.” As a rule, hymn boards were not used.

At the signal from the schoolmaster, hundreds or even thousands of voices filled the church. Pastor Seib said the singing was so impressive that it "penetrated to the very marrow." Volga Germans liked to sing and sing loud. The ruddy complexions of the church attendees were witness to the fact that singing was an essential part of worship. Parishioners were serious about singing. It is said that people braced their legs on the back of pews to be able to sing with all their might.

In general, congregational singing was very satisfactory. However, Pastor Seib reported that "the bad habit" of singing hymns too slowly (dragging) and women singing tenor was still practiced in some places.

The second floor held the choir and the great pipe organ. The choir consisted of unmarried men and women who would sing two or three selections aside from the congregational singing. The choirmaster was known in German as the Chorleiter. The job of the Chorleiter was to give the choir or congregation the musical pitch by striking a tuning fork against the metal music stand and then raising it with all to listen to carefully and hum the tone in their heads, thus giving the musical pitch for all the basses, tenors, altos and sopranos to be in harmony (a four-part harmony). Then, the organ began to play, and either the choir and/or the congregation chimed in with the singing of that specific hymn. The role of the Chorleiter was very significant and necessary. His job was to lead the singing but also to bring the singing together in a harmonious tonal quality. The choirs sang for festivals and every Sunday, except in the summer when the farmers had no time for anything except farming.

Church services lasted one hour and forty-five minutes, and the sermon was delivered from the suspended pulpit. The congregation stood from the beginning to the end of the liturgy. If “Jesus Christ” was mentioned, the women bent a knee. During the sermon, the audience would nod approvingly if something in the sermon pleased them, and they repeated the mentioned Bible verses aloud. This showed how attentively the audience listened to the sermon and how well the people memorized many Bible verses.

Pastor Seib wrote, "It is truly a joy to preach in the colonies along the Volga!"

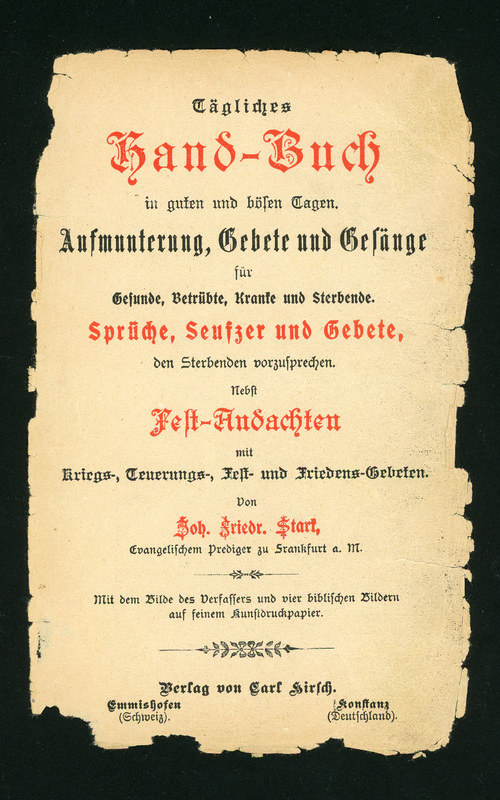

If the pastor was serving another colony in his parish, the Schulmeister (schoolmaster) reads from books approved by the pastor. The books generally used were Brastberger's, Schoner's, Stark's and Francke's. Prayers could be read from the books of Arndt and Schmolk.

Title page from "Tägliches Handbuch in guten und bösen Tagen, für Gesunde, Betrübte, Kranke und Sterbende" by Johann Friedrich Stark (1680-1756), a pietistic Lutheran theologian. This book was owned by Heinrich Döring and brought with him from Norka to the United States. Courtesy of Steve Schreiber.

Several men were elected Kirchenvorsteher in the parish (Church Wardens). The role of the Kirchenvorsteher was to be a role model by participating in church life and demonstrating Christian conduct. This group of men also carried purses with little bells attached to receive the free-will offerings of the congregation.

On Sunday afternoons, children and adults were catechized. If conducted by the pastor, it was usually about the gospel he covered that day or some other passage of Scripture. If performed by the schoolmaster, he merely asked the questions contained in the catechism used at school and read one or two chapters from the Bible.

Typically, baptisms were performed within several weeks of a child's birth. In a typical ceremony, parents or godparents bring their child to the pastor of the church congregation.

Historically, confirmation is an ecclesiastical event confirming young people’s baptism and belief. Confirmation also signaled an end to the juvenile phase of life and entry into the ecclesiastical and religious life of adults. The confirmation ritual was widespread in the German-speaking parts of Europe during the 18th century. This practice was brought to Russia by the colonists and their religious leaders. Confirmation classes were presented to the church congregation on Palm Sunday. Sometimes, confirmation occurred on Pentecost.

The times determined for the celebration of the Lord’s Supper (Communion) were chosen with great reverence and solemnity, between Easter and Pentecost in springtime and after the harvest in autumn.

Weddings were often held during the week between Christmas and the Neujahrsfeier (New Year's celebration) or during the winter months when there was no field work, a time when nature itself seemed to bless the union.

Funerals included a church service followed by a procession that led the mourners to the cemetery where the burial rites occurred.

Typically, baptisms were performed within several weeks of a child's birth. In a typical ceremony, parents or godparents bring their child to the pastor of the church congregation.

Historically, confirmation is an ecclesiastical event confirming young people’s baptism and belief. Confirmation also signaled an end to the juvenile phase of life and entry into the ecclesiastical and religious life of adults. The confirmation ritual was widespread in the German-speaking parts of Europe during the 18th century. This practice was brought to Russia by the colonists and their religious leaders. Confirmation classes were presented to the church congregation on Palm Sunday. Sometimes, confirmation occurred on Pentecost.

The times determined for the celebration of the Lord’s Supper (Communion) were chosen with great reverence and solemnity, between Easter and Pentecost in springtime and after the harvest in autumn.

Weddings were often held during the week between Christmas and the Neujahrsfeier (New Year's celebration) or during the winter months when there was no field work, a time when nature itself seemed to bless the union.

Funerals included a church service followed by a procession that led the mourners to the cemetery where the burial rites occurred.

Norka choir in 1906 with Rev. Stärkel seated in the center. The choir included unmarried men and women as well as children. Standing behind Rev. Stärkel is the Chorleiter (Choir Leader), Karl Leonhardt, holding a tuning fork in his right hand and a Wolga Gesangbuch (Volga Song Book) in his left hand. These objects symbolized the Chorleiter's leadership and authority in conducting and leading the singing. To the extreme left of the photograph is the Schulmeister holding a Bible or Wolga Gesangbuch. The Schulmeister was the school master or as we would say today the "principal" of the school. His job was to take the place of the pastor for the leading of the ordinary worship service and in some cases for funerals and baptisms where the pastor was unavailable. The Schulmeister also assisted the pastor in visitation of the sick along with one or two elders of the church. This particular person wore a long suit jacket, it looked like a coat. This was considered a formal dressware for the Schulmeister to be worn in the church. While the pastor wore the pulpit gown or (der Mantel). Sometimes the Schulmeister also wore a small cross-stitch tie similar to the one worn by all the Lutheran and Reformed pastors as in the case of Rev. Stärkel. The cross-stitch tie was worn as a symbol by Luther and Zwingli protestant reformers. Photograph courtesy of Lynn Huber and Lois K. Klaus. This photo belonged to Jacob K. Klaus of Portland, Oregon.

The large bell was tolled when the Lord’s Prayer was said to conclude the service. At its first clanging, those left at home stopped everything they were doing, folded their hands, and prayed the Lord’s Prayer with those physically present in the church building. After that, the noodles were put into the pot belly stove (Kroppa), and the noon meal of noodle soup or cabbage (with other vegetables) and mashed potatoes (or just mash) with pork was readied so that churchgoers could sit down at the table immediately after they returned home.

After the worship service, the congregation exited the church in a specific order. The women exited according to their birth year, and then the men would leave. On the way home, the people discussed the sermon, especially the parts that emotionally affected the parishioners. Sometimes, the audience was moved to tears. If the sermon did not arouse any criticism or was uninspiring, the congregation returned home in a reflective mood.

Of course, some people were infrequent worshipers, as captured in the anecdote about the parishioner who exclaimed: "It's a strange thing, but every time I come to church, they have a Christmas tree standing there!"

After the worship service, the congregation exited the church in a specific order. The women exited according to their birth year, and then the men would leave. On the way home, the people discussed the sermon, especially the parts that emotionally affected the parishioners. Sometimes, the audience was moved to tears. If the sermon did not arouse any criticism or was uninspiring, the congregation returned home in a reflective mood.

Of course, some people were infrequent worshipers, as captured in the anecdote about the parishioner who exclaimed: "It's a strange thing, but every time I come to church, they have a Christmas tree standing there!"

Sources

Bauer, Milton P. Untitled manuscript dated May 1977, Portland, Oregon.

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1985. Print.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977.129. Print.

Schnurr, Joseph. Die Kirchen Und Das Religiöse Leben Der Rußlanddeutschen. Stuttgart: AER-Verl., 1978. Print.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums." Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): Print.

"Protestantism in Russia." Christian Reflector & Christian Watchman [Boston] 17 Aug. 1848: Print.

Brill, Conrad. "Memories of Norka." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1985. Print.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977.129. Print.

Schnurr, Joseph. Die Kirchen Und Das Religiöse Leben Der Rußlanddeutschen. Stuttgart: AER-Verl., 1978. Print.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums." Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): Print.

"Protestantism in Russia." Christian Reflector & Christian Watchman [Boston] 17 Aug. 1848: Print.

Last updated June 27, 2024