Sarpinka

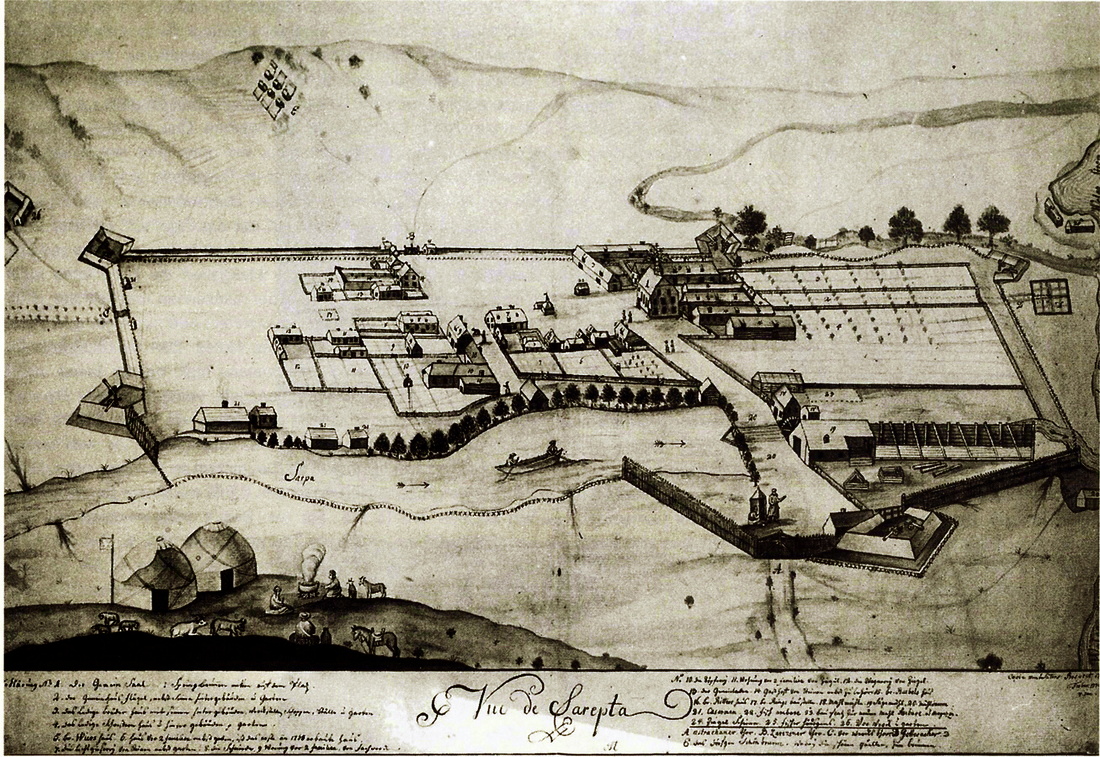

Industrial weaving was first developed in the Moravian colony of Sarepta (near Volgograd) in the late 1770s. As a result, the fabric produced by the colonists received the name sarpinka. Sarpinka is a fine gingham material woven from dyed cotton yarn.

The expensive and unpredictable delivery of cotton yarn from abroad encouraged the Sarepta merchants to produce it themselves from cotton imported through Astrakhan from Persia. These efforts were rewarded with success. Given the small population of the Sarepta colony, the merchants decided to have the yarn necessary for the production of cloth produced first in the colonies of Sosnovka (Schilling), Popovka (Jost), then in Sebastjanovka (Anton), Splavnukha (Huck), Norka, Golyi Karamysh (Balzer), and Lesnoi Karamysh (Grimm). The work was done in homes during the winter and then transported to the Sarepta factories.

Gradually, cloth production increased so much that Sarepta, which did not have enough laborers, needed to consider expanding its operation. Sarepta was also a long distance from the main transportation center in Saratov. Workers who came to Sarepta from other colonies learned the trade and often began operations in their home villages.

In 1810, the Sarepta merchants opened a large weaving operation in Norka, which provided more labor and close proximity to Saratov. The operation in Norka was the first in the Volga German colonies and one of the largest producers of Sarpinka in the Volga region.

There were many religious and business ties between Norka and Sarepta, including Pastor Friedrich Börner, who married Johanna Martha Eleonore Metzger in June 1830. She was the daughter of Sarepta factory owner Johannes Metzger and Maria Salome Messerschmidt.

In 1810, the Sarepta merchants opened a large weaving operation in Norka, which provided more labor and close proximity to Saratov. The operation in Norka was the first in the Volga German colonies and one of the largest producers of Sarpinka in the Volga region.

There were many religious and business ties between Norka and Sarepta, including Pastor Friedrich Börner, who married Johanna Martha Eleonore Metzger in June 1830. She was the daughter of Sarepta factory owner Johannes Metzger and Maria Salome Messerschmidt.

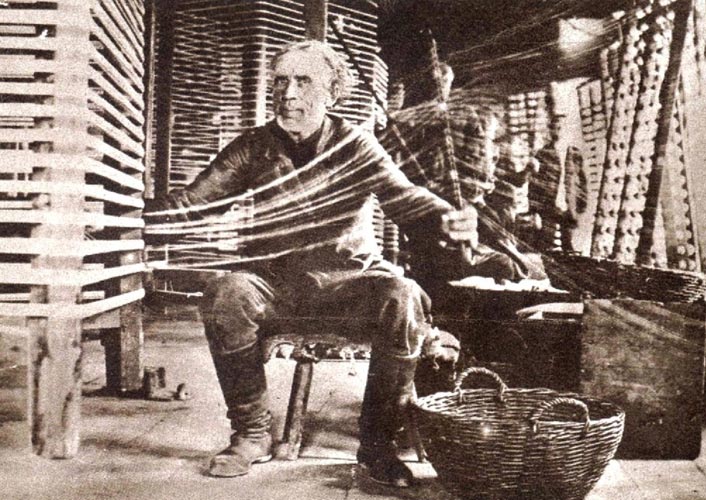

Weaving was a simple skill that could be learned in about a month and required only an inexpensive spinning wheel or handloom. Many weavers worked alone in their homes from October to April or whenever they were free from fieldwork. Originally, weaving was male-dominated, but by 1900, half of the weavers were women. Children and the elderly would sit near the weavers, where they would thread yarn onto spools. The long hours and backbreaking work took their toll on the weavers, some of whom labored for up to 16 hours per day in an unnatural position that strained the back muscles. Humped, or weaver's back, and arthritic hands were common physical afflictions.

Agents of Russian factory owners soon set up their own factories in the colonies and increased salaries. At about the same time, English machine-produced cloth gained access to Russia and could be sold at a much lower price than the handmade sarpinka. In addition, the colonists began making their own sarpinka at lower prices. Because of all of the competition, Sarepta transferred all production to Saratov in 1816.

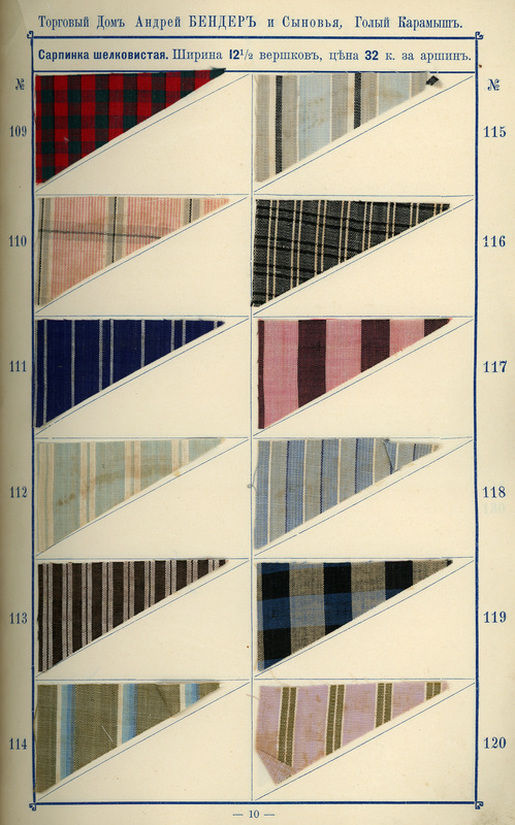

Energetic German merchants in Saratov entered the sarpinka business, eventually forcing the Sareptans to discontinue production in 1821. The Schechtel brothers dominated the market until they bankrupted themselves, looking for gold in Siberia. This allowed more powerful entrepreneurs into the sarpinka market. By the 1850s, the market was controlled by the "Cotton Kings" - the Schmidt, Borel, and Reinecke families who not only opened factories in their native colonies but also in Lesnoi Karamysh (Grimm), Gololobovka (Dönhof), Splavnukha (Huck), and Norka.

Several entrepreneurs from Norka exhibited their work internationally. The International Exhibition of 1862, or the Great London Exposition, was a world's fair. It was held from May 1 to November 1, 1862. The exposition was sponsored by the Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures, and Trade and featured over 28,000 exhibitors from 36 countries, representing a wide range of industry, technology, and the arts. All told it attracted about 6.1 million visitors.

Agents of Russian factory owners soon set up their own factories in the colonies and increased salaries. At about the same time, English machine-produced cloth gained access to Russia and could be sold at a much lower price than the handmade sarpinka. In addition, the colonists began making their own sarpinka at lower prices. Because of all of the competition, Sarepta transferred all production to Saratov in 1816.

Energetic German merchants in Saratov entered the sarpinka business, eventually forcing the Sareptans to discontinue production in 1821. The Schechtel brothers dominated the market until they bankrupted themselves, looking for gold in Siberia. This allowed more powerful entrepreneurs into the sarpinka market. By the 1850s, the market was controlled by the "Cotton Kings" - the Schmidt, Borel, and Reinecke families who not only opened factories in their native colonies but also in Lesnoi Karamysh (Grimm), Gololobovka (Dönhof), Splavnukha (Huck), and Norka.

Several entrepreneurs from Norka exhibited their work internationally. The International Exhibition of 1862, or the Great London Exposition, was a world's fair. It was held from May 1 to November 1, 1862. The exposition was sponsored by the Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures, and Trade and featured over 28,000 exhibitors from 36 countries, representing a wide range of industry, technology, and the arts. All told it attracted about 6.1 million visitors.

The Official Catalogue of the Industrial Department lists two cotton cloth exhibitors, J. Deiness (Deines) and W. Spadi (Spady) from Norka (shown in the catalog as "Norki Settlement, Saratof Gov."). Other Volga German merchants were also listed as exhibitors.

By 1866, there were 69 sarpinka factories in which there worked up to 6,000 weaving machines that produced up to 30,000 pud (540 tons) of yarn. Dresses and other materials were also produced.

In 1894, about 250 people in Norka were engaged in the sarpinka industry. Some children, as young as 7 years old, were employed.

In 1901, the first textile factory in the region was opened in Norka.

Over time, the sarpinka industry remained consolidated into the hands of only a few families. At the outbreak of World War I, seventeen families controlled the business; of those, five families employed 60 percent of the weavers.

By 1866, there were 69 sarpinka factories in which there worked up to 6,000 weaving machines that produced up to 30,000 pud (540 tons) of yarn. Dresses and other materials were also produced.

In 1894, about 250 people in Norka were engaged in the sarpinka industry. Some children, as young as 7 years old, were employed.

In 1901, the first textile factory in the region was opened in Norka.

Over time, the sarpinka industry remained consolidated into the hands of only a few families. At the outbreak of World War I, seventeen families controlled the business; of those, five families employed 60 percent of the weavers.

Sources

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Printed by Augstums Printing Service, 2005: 255. Print.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 140-143. Print.

Mertens, Ulrich, Allyn Brosz, Alex Herzog, and Thomas Stangl. German-Russian Handbook: A Reference Book for Russian German and German Russian History and Culture with Place Listings of Former German Settlement Areas. Fargo, ND: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State U Libraries, 2010. Print.

Official Catalogue of the Industrial Department (from the 1862 International Exhibition in London, England). United Kingdom: Cambridge UK, 1862. Print. p. 380.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. 140-143. Print.

Mertens, Ulrich, Allyn Brosz, Alex Herzog, and Thomas Stangl. German-Russian Handbook: A Reference Book for Russian German and German Russian History and Culture with Place Listings of Former German Settlement Areas. Fargo, ND: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State U Libraries, 2010. Print.

Official Catalogue of the Industrial Department (from the 1862 International Exhibition in London, England). United Kingdom: Cambridge UK, 1862. Print. p. 380.

Last updated November 26, 2023