History > Famine 1921-1924

Famine 1921-1924

The Volga Germans experienced periodic droughts and famines from settlement in 1767 up to the Bolshevik Revolution. Before 1921, the most recent famine had occurred in 1892.

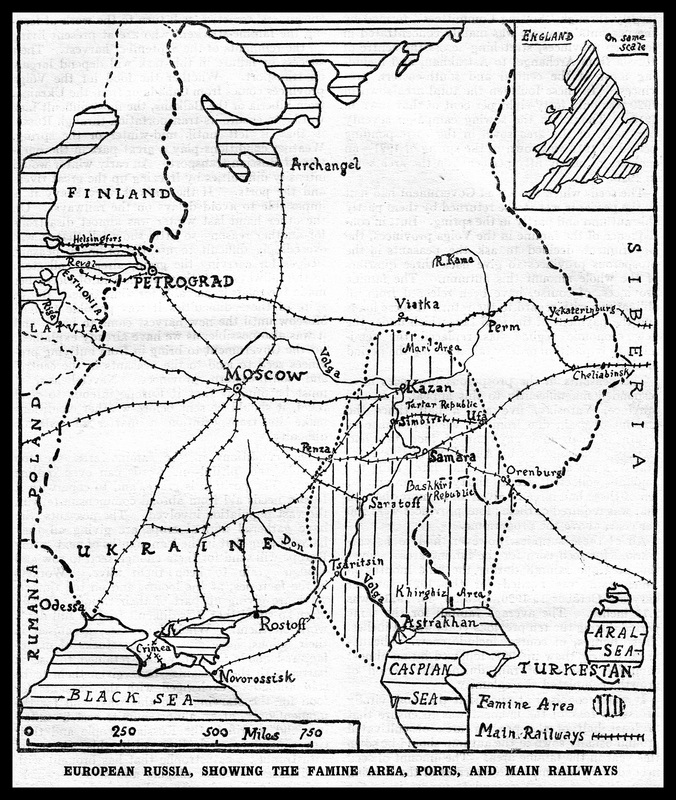

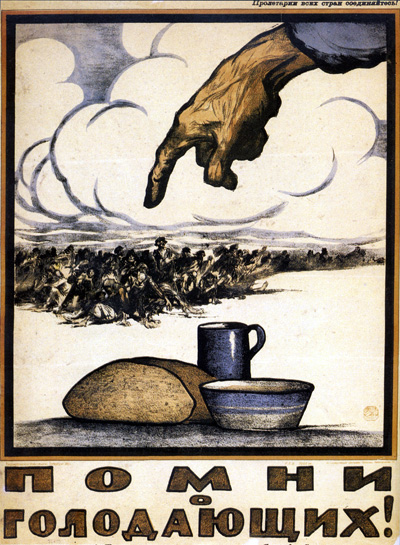

The Russian Povolzhye (Volga region) famine of 1921 began early that year, and its terrible impact was felt in Norka through 1924. It is estimated that this famine claimed the lives of 5 million people. The famine stemmed from both natural and human causes.

A poor crop in 1920 was made worse by the disruption of agricultural production, which started during World War I and continued through the disturbances of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and Civil War. The Bolshevik policies of War Communism (keeping the Red Army stocked with weapons and food) and prodrazvyorstka (a campaign to confiscate grain and agricultural products) had set the stage for a large-scale human tragedy.

Mass confiscation of stored grain began in the winter of 1920-21, triggering the beginning of famine in January 1921. In many cases, the recklessness of the local administration, which recognized the problems only too late, contributed to the problem. Hunger was so severe that it was doubtful that seed grain would be sown rather than eaten.

Without seeds to plant, the famine worsened in the spring of 1921, and people sold all they had to survive. Drought struck a hard blow to the Volga region in the summer of 1921, resulting in a total crop failure. With death all around, cholera and spotted fever were rampant.

The Russian Povolzhye (Volga region) famine of 1921 began early that year, and its terrible impact was felt in Norka through 1924. It is estimated that this famine claimed the lives of 5 million people. The famine stemmed from both natural and human causes.

A poor crop in 1920 was made worse by the disruption of agricultural production, which started during World War I and continued through the disturbances of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and Civil War. The Bolshevik policies of War Communism (keeping the Red Army stocked with weapons and food) and prodrazvyorstka (a campaign to confiscate grain and agricultural products) had set the stage for a large-scale human tragedy.

Mass confiscation of stored grain began in the winter of 1920-21, triggering the beginning of famine in January 1921. In many cases, the recklessness of the local administration, which recognized the problems only too late, contributed to the problem. Hunger was so severe that it was doubtful that seed grain would be sown rather than eaten.

Without seeds to plant, the famine worsened in the spring of 1921, and people sold all they had to survive. Drought struck a hard blow to the Volga region in the summer of 1921, resulting in a total crop failure. With death all around, cholera and spotted fever were rampant.

The American Relief Administration (ARA), which Herbert Hoover had formed to assist those starving due to World War I and the Russian Civil War, offered assistance to Vladimir Lenin in 1919. Lenin refused this offer as interference in Russian internal affairs.

The growing famine in 1921 and other political pressures convinced Lenin to reverse his policy. He decreed a New Economic Policy on March 15, 1921, which belatedly allowed relief organizations to bring aid.

George Repp, a native of Norka and a founder of the Volga Relief Society in Portland, Oregon, became a prominent member of the ARA that saved thousands of Volga German families from starvation in the early 1920s. Repp unselfishly left his family and business in Portland to lead relief efforts in the Volga German colonies and his hometown of Norka.

Repp reported the following when he arrived in the city of Saratov on October 14, 1921:

The growing famine in 1921 and other political pressures convinced Lenin to reverse his policy. He decreed a New Economic Policy on March 15, 1921, which belatedly allowed relief organizations to bring aid.

George Repp, a native of Norka and a founder of the Volga Relief Society in Portland, Oregon, became a prominent member of the ARA that saved thousands of Volga German families from starvation in the early 1920s. Repp unselfishly left his family and business in Portland to lead relief efforts in the Volga German colonies and his hometown of Norka.

Repp reported the following when he arrived in the city of Saratov on October 14, 1921:

"The first thing we saw was from fifteen hundred to two thousand people on the banks of the Volga, without food and in rags, mostly Germans, and all bound for somewhere, none of them knowing really where they wanted to go, but just to get away. Everything they possessed in this world they had with them; a good many were sick from exposure and hunger. They went about the city of Saratov picking up potato peelings, melon rinds, cabbage leaves, and in fact, anything that could be eaten. As fast as they could get transportation, either north or south, east or west, by rail or boat, they left."

Repp arrived in the Volga River port colony of Schilling in early November 1921. He immediately began to organize food kitchens to help the most needy. About 200 children of the poorest families were fed first on November 6th. One little boy, impatient to eat, asked Repp, "Uncle, when will the kitchens open?" When he was told the cooks were a little slow, the boy suggested an immediate remedy, "Let's throw them in the Volga."

Repp arrived in nearby Norka on November 7th and found a dire situation. Rev. Wacker reported that there were over 2,000 children in the colony, of which 75 percent were starving. The committee of 13 men organized by Repp had to make agonizing decisions about which children to feed first. The committee often visited the families to determine those in greatest need.

The three kitchens in Norka were opened on November 14th, but only 500 people could be fed on the first day. The committee decided to use the schoolhouses as feeding stations, and the teacher's backhäuser (bakehouses) were used for cooking. The committee had to collect utensils and water and hire cooks to do the work. The cooks were not paid with money but received a double food ration. The response was overwhelming. Rev. Wacker reported that the applicants responded: "With tears of joy for those who were chosen, and tears of sorrow for those who had been dropped." Food supplies were brought in on wagons from Schilling. Initially, enough food was brought to last for six weeks.

In a letter, Rev. Wacker described the opening day of the kitchens in Norka:

Repp arrived in nearby Norka on November 7th and found a dire situation. Rev. Wacker reported that there were over 2,000 children in the colony, of which 75 percent were starving. The committee of 13 men organized by Repp had to make agonizing decisions about which children to feed first. The committee often visited the families to determine those in greatest need.

The three kitchens in Norka were opened on November 14th, but only 500 people could be fed on the first day. The committee decided to use the schoolhouses as feeding stations, and the teacher's backhäuser (bakehouses) were used for cooking. The committee had to collect utensils and water and hire cooks to do the work. The cooks were not paid with money but received a double food ration. The response was overwhelming. Rev. Wacker reported that the applicants responded: "With tears of joy for those who were chosen, and tears of sorrow for those who had been dropped." Food supplies were brought in on wagons from Schilling. Initially, enough food was brought to last for six weeks.

In a letter, Rev. Wacker described the opening day of the kitchens in Norka:

On the morning of November 14, the smoke from the kitchen chimneys rose to the wintry heavens. Every child who possessed an admittance card armed himself with a plate and spoon. Although the food was not served until noon, the kitchens reminded one of a besieged fortress by ten o'clock... Finally, the doors opened, and in wild confusion, but finally every child found a place... A board which had been placed over two school benches acted as the serving table. Upon it lay pieces of bread which blinded one with their whiteness. None of us had seen such bread for years, and to the poorer children it was something entirely new. From here I went into the kitchen where two cooks were stirring the rice porridge, which was being cooked in ten or twelve large kettles. This was Monday and according to the American (ARA) program, cocoa should have been prepared, but because of the bad roads from Schilling, it had not arrived yet. Consequently, the children are given rice porridge on two successive days. In the meantime, the member of the committee were showing the children to their places. Everything seems to be taking too long in the little fellows' opinion, and as some waited for their names to be read, the others, who already had a place moved impatiently on their benches in expectation of the things that were to come. Several of them examined their plates once more on the outside and inside, as if they wanted to convince themselves that none of the precious porridge would be lost.

During the first meals served, Rev. Wacker observed a three-year-old girl who seemed afraid to take some of the bread when it was passed around in a large basket. He shared his puzzlement:

I do not know if it was mere shyness or if she suddenly could not understand the meaning of it all. She had already heard that strange men would come and take away the people's bread, but now strange men had come and brought bread.

In a letter to John W. Miller dated February 13, 1922, Repp reported that they were feeding 35,000 souls on the Bergseite, and by February 24th, they would be feeding 40,000. Repp also wrote that there would soon be enough food to begin feeding adults.

In addition to feeding the most needy, seed grain was provided in hopes of creating a successful harvest in 1922. Clothing was also provided to the extent possible. Records from the Volga Relief Society show that many families in the United States sent both money and clothing to Norka for those in need.

In addition to feeding the most needy, seed grain was provided in hopes of creating a successful harvest in 1922. Clothing was also provided to the extent possible. Records from the Volga Relief Society show that many families in the United States sent both money and clothing to Norka for those in need.

Throughout 1922 and 1923, the famine was still widespread, and the ARA continued to provide relief supplies. Meanwhile, grain was being exported by the Soviet government to raise funds for industry revival. These actions seriously endangered Western support for the relief effort and made clear the long-standing Soviet policy of valuing development above the lives of the rural population.

Rev. Wacker reported a moderate harvest in 1922 and a poor harvest in 1923, made worse by an "in-kind" tax on the grain, which left the people with little to live on. Wacker's letters to friends in the United States continued support for the relief effort.

Many people, including Conrad Brill, left the desperate situation in Norka and emigrated through Germany to the United States or Canada. Brill and others from Norka found a temporary safe haven at the Heimkehrlager (Homecoming camp), a displaced persons camp at Frankfurt an der Oder. An article in the German language newspaper Heimkehr reported the following arrivals from Norka at the Frankfurt/Oder camp in early 1922:

In April 1922, several more people from Norka arrived at the Frankfurt/Oder camp:

Difficult conditions prevailed in Norka into 1924, as this excerpt from a letter written by Heinrich and Christina Burbach on May 3, 1924, to their family in America demonstrates:

Rev. Wacker reported a moderate harvest in 1922 and a poor harvest in 1923, made worse by an "in-kind" tax on the grain, which left the people with little to live on. Wacker's letters to friends in the United States continued support for the relief effort.

Many people, including Conrad Brill, left the desperate situation in Norka and emigrated through Germany to the United States or Canada. Brill and others from Norka found a temporary safe haven at the Heimkehrlager (Homecoming camp), a displaced persons camp at Frankfurt an der Oder. An article in the German language newspaper Heimkehr reported the following arrivals from Norka at the Frankfurt/Oder camp in early 1922:

- Heinrich Grün, 72 years old, with wife and son.

- Heinrich Sinner

- Johann Bauer with wife Marie and 4 children

- Hermann Hohnstein with wife Anna and 3 children

- Katherine Wert (Werth?)

In April 1922, several more people from Norka arrived at the Frankfurt/Oder camp:

- Jakob and Katharina Döring (born 1 June 1893 and 10 March 1895)

- Katharina Kielthau (probably Külthau, born 10 November 1895)

- Margarete and Elisabeth Brill

- Alexander Schnell

Difficult conditions prevailed in Norka into 1924, as this excerpt from a letter written by Heinrich and Christina Burbach on May 3, 1924, to their family in America demonstrates:

"Blessings and peace be with you and an affectionate kiss and greetings of love from us, Heinrich and Christina Burbach, to you dear cousin Elisabeth and your husband and children.

You ask how it goes with us--here things are going very poorly. Time has taken everything from us. You know how it once was and now we are so poor. We have 2 fields that we work, we have no cow, only 2 sheep. You cannot imagine our poverty. We have no seed to sow and also nothing to live on. Our children ask; "What is there still to eat?" We cannot rely on you dear brothers and sisters because you have your father to deal with. But if it is not too difficult, could you help us a little?"

Many heart-breaking letters were written between family, friends, and the Volga German clergy living in Russia and North America during the famine. These letters were often published in Die Welt-Post (The World Post), a German-language newspaper established initially in Lincoln, Nebraska. Some letters, like those received by the Sinner family, were kept privately.

While the situation remained fragile, conditions slowly improved in the late 1920s when one of Norka's native sons, Heinrich Wacker, came from Amerika to visit his homeland. Wacker wanted to see firsthand what had happened to family and friends living in Norka and would report back to those living in the United States and Canada with stories and a rare film.

The population of Norka declined from over 14,000 in 1912 to under 7,000 by 1923. While some of the decrease was undoubtedly due to emigration, the impact of wars, and the Bolshevik Revolution, there is no doubt that the famine had taken a tremendous toll on the colony of Norka. Peter Sinner states that one-third of the Volga German population died from 1921 to 1924.

There was a relative improvement in life for the people of Norka for a brief period in the late 1920s and early 1930s. By 1932, a politically motivated famine would soon ravage the Volga region and Ukraine, and by the mid-1930s, Stalin's Great Terror would descend like a dark cloud over all of Russia.

While the situation remained fragile, conditions slowly improved in the late 1920s when one of Norka's native sons, Heinrich Wacker, came from Amerika to visit his homeland. Wacker wanted to see firsthand what had happened to family and friends living in Norka and would report back to those living in the United States and Canada with stories and a rare film.

The population of Norka declined from over 14,000 in 1912 to under 7,000 by 1923. While some of the decrease was undoubtedly due to emigration, the impact of wars, and the Bolshevik Revolution, there is no doubt that the famine had taken a tremendous toll on the colony of Norka. Peter Sinner states that one-third of the Volga German population died from 1921 to 1924.

There was a relative improvement in life for the people of Norka for a brief period in the late 1920s and early 1930s. By 1932, a politically motivated famine would soon ravage the Volga region and Ukraine, and by the mid-1930s, Stalin's Great Terror would descend like a dark cloud over all of Russia.

|

|

|

Sources

Famine letters published in Die Welt-Post

Haynes, Emma S. A History of the Volga Relief Society. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1982. Print.

Patenaude, Bertrand M. The Big Show in Bololand: The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the Famine of 1921. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2002. Print.

Sinner, Peter. Germans in the Land of the Volga. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1989. Print.

Sinner, Samuel. "Famine in the Volga Basin, 1920-1924, and the American Volga Relief Society Records." Nebraska History 78 (1997): 134-38. Print.

Walters, George J. Wir Wollen Deutsche Bleiben (We Want to Remain German): The Story of the Volga Germans. Kansas City, MO: Halcyon House, 1982. 187-208. Print.

Volga Relief Society list of donations from the United States to people in Norka 1922-23.

Haynes, Emma S. A History of the Volga Relief Society. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1982. Print.

Patenaude, Bertrand M. The Big Show in Bololand: The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the Famine of 1921. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2002. Print.

Sinner, Peter. Germans in the Land of the Volga. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1989. Print.

Sinner, Samuel. "Famine in the Volga Basin, 1920-1924, and the American Volga Relief Society Records." Nebraska History 78 (1997): 134-38. Print.

Walters, George J. Wir Wollen Deutsche Bleiben (We Want to Remain German): The Story of the Volga Germans. Kansas City, MO: Halcyon House, 1982. 187-208. Print.

Volga Relief Society list of donations from the United States to people in Norka 1922-23.

Last updated November 26, 2023