People > Notable Norkans > George Repp

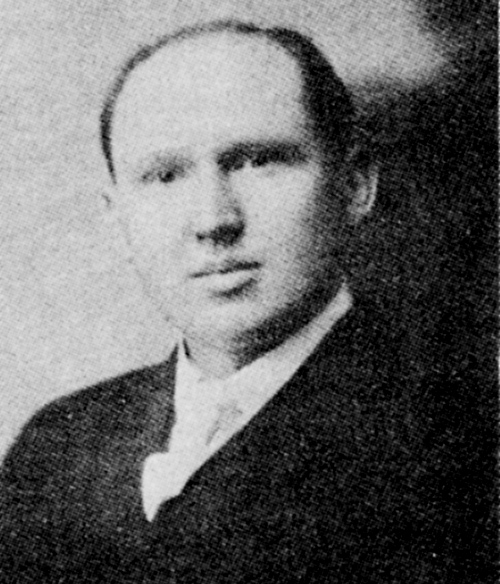

George Repp

Historians have described the famine relief work accomplished along the Volga River during the years 1921-1923 as the most outstanding act of charity ever performed by the Volga Germans now living in the United States. George Repp was one of the leaders who organized the Volga Relief Society and is one of the greatest humanitarians among the Volga Germans.

George was born in Norka in 1886, and his family history can be traced to the original colonists who settled there. When he was five months old, his parents, Conrad Repp and his wife Anna Maria (née Weidenkeller), immigrated to the United States. Conrad Repp died on August 13, 1916, and the operation of his well-known grocery store in Portland, Oregon, passed to his sons, George and Adam. The grocery business was renamed Repp Brothers Grocery and Meats.

In 1921, the Repps began to learn about the worsening conditions in Russia due to the Bolshevik Revolution and the resulting Civil War.

The Volga Germans were among those forced to give up their seed wheat due to what was known as "requisitioning," or the confiscation by Soviet authorities. Then, in the fall of 1920 and 1921, crop failures occurred along the Volga, and one of the greatest famines in many years set in.

According to author E.M. Halliday,

In 1921, the Repps began to learn about the worsening conditions in Russia due to the Bolshevik Revolution and the resulting Civil War.

The Volga Germans were among those forced to give up their seed wheat due to what was known as "requisitioning," or the confiscation by Soviet authorities. Then, in the fall of 1920 and 1921, crop failures occurred along the Volga, and one of the greatest famines in many years set in.

According to author E.M. Halliday,

The natural causes of Russia’s distress in 1921-22 were the same as those of thirty years earlier—a blistering drought, followed by an unusually cold winter —but now these were starkly assisted by the aftermath of World War I and the civil war between the Reds and the Whites. The loss of millions of peasant farmers who had gone off to serve and die in the various armies had already reduced grain production by twenty-five per cent, and the Bolsheviks’ ruthless policy of “military communism,” whereby food was forcefully taken from the peasants whenever necessary, further interfered with normal production: there was, in effect, an agricultural strike. Transportation also broke down severely, pestilence swept across the land, and the Communist leaders saw their social experiment threatened by economic paralysis and starvation.

Given that foreign newspaper correspondents were not allowed in Russia then, little was known about the famine until an article in the Literary Digest on August 6, 1921, was published. The article is titled "Millions Starving in Lenin's Paradise of Atheism." George and Katherine Repp were subscribers to the Literary Digest, and the article greatly impacted them.

The Repps felt an urgent need to form an organization that would send food aid and clothing to the Volga German colonies. Their plan was then discussed with Katherine Repp's brother, John W. Miller, who enthusiastically embraced it.

George and his brother-in-law, John Miller, took the first steps to organize the Volga Relief Society in Portland. Before talking with the Volga German community, John wrote to the American Relief Administration (A.R.A.) in New York under Herbert Hoover's leadership. The following letter was sent on August 8, 1921:

The Repps felt an urgent need to form an organization that would send food aid and clothing to the Volga German colonies. Their plan was then discussed with Katherine Repp's brother, John W. Miller, who enthusiastically embraced it.

George and his brother-in-law, John Miller, took the first steps to organize the Volga Relief Society in Portland. Before talking with the Volga German community, John wrote to the American Relief Administration (A.R.A.) in New York under Herbert Hoover's leadership. The following letter was sent on August 8, 1921:

European Relief Committee, 42 Broadway, New York City.

There are approximately fifteen hundred people in Portland that came from German colonies located in Russia near city of Saratov along Volga River. These people are anxious to help get food into that stricken district of Russia. They have received letters from relatives appealing for help. Will you be good enough to wire us how to proceed. That is, can we send money to you and designate that it is to be spent for food for a certain colony. Also have you any idea when relief work and food distribution will begin in Russia. There will be a mass meeting Thursday evening among our people and a regular relief committee organized for German speaking colonies in Russia. We would like very much have your reply by then giving us all information you can that may help in the organization. Have hopes extending work of this committee to other places where our people are located in California, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Colorado, Dakotas, Nebraska, Iowa, and Kansas. We figure that there are in the United States approximately hundred thousand people interested in these German speaking colonies along the Volga River and that good work can be done with proper help from reliable source like yourselves. Would it be possible for us to send an American citizen of our people into these colonies in Russia through your committee? That is, be indorsed by you or even sent by you as one of your workers so that he would have proper protection.

John W. Miller

A response from Edgar Rickard of the A.R.A. was sent to John W. Miller, accepting the offer of assistance from the Volga Relief Society.

Emma Schwabenland Haynes states that the Volga Relief Society was organized in Portland, Oregon, on August 11, 1921, in the Zion German Congregational Church. Their stated purpose was to raise funds for relatives along the Volga River, who, at that time, were suffering from one of the most disastrous famines in European history. At this meeting, John W. Miller was chosen president, and George Repp was to be its representative in Russia, working under the supervision of the A.R.A. Haynes states:

Emma Schwabenland Haynes states that the Volga Relief Society was organized in Portland, Oregon, on August 11, 1921, in the Zion German Congregational Church. Their stated purpose was to raise funds for relatives along the Volga River, who, at that time, were suffering from one of the most disastrous famines in European history. At this meeting, John W. Miller was chosen president, and George Repp was to be its representative in Russia, working under the supervision of the A.R.A. Haynes states:

The enthusiastic response of the Portland people to the news that an organization had been perfected was far greater than anyone could have believed possible. Throughout the following days the newly elected leaders were constantly being stopped by Volga German men and women who expressed their happiness in the creation of the society. In view of the seriousness of the crisis that existed in Russia, all religious and personal differences were forgotten, and people of all denominations and from all colonies showed a spirit of harmony and cooperation that was to remain truly remarkable. The future success of the Volga Relief Society can be explained to a great extent by the splendid loyalty of its members, which became an example for Volga Germans in many other communities of the States.

On August 23rd, after the formation of the society in Portland, John W. Miller sent a letter to every German Congregational Church in the United States and Canada, which were nearly all German-speaking people from Russia. As a result, similar gatherings were held by Volga Germans living in Fresno, California, and in Lincoln, Nebraska. Before long, money was contributed by communities in Colorado, Washington, Montana, Oklahoma, Illinois, Kansas, and many other states in which the Volga German people had settled.

George's decision to assist with the relief efforts in Russia was a significant personal sacrifice. In his mid-30s, he would leave his family and business interests for one year and subject himself to considerable health and physical risks. George spoke the German dialect of his parents and neighbors from Norka, but sources indicate that he needed an interpreter to communicate with Russian speakers.

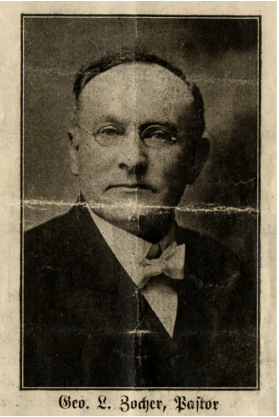

During the first week of September 1921, a meeting in honor of George was held at the First German Congregational Church (Ebenezer), where 154 people pledged $1,250 monthly for one year to support the relief work. Judge Jacob Kanzler was the first to address the capacity crowd in the church. Rev. George Zocher then made an address dedicating George to his work in Russia.

George's decision to assist with the relief efforts in Russia was a significant personal sacrifice. In his mid-30s, he would leave his family and business interests for one year and subject himself to considerable health and physical risks. George spoke the German dialect of his parents and neighbors from Norka, but sources indicate that he needed an interpreter to communicate with Russian speakers.

During the first week of September 1921, a meeting in honor of George was held at the First German Congregational Church (Ebenezer), where 154 people pledged $1,250 monthly for one year to support the relief work. Judge Jacob Kanzler was the first to address the capacity crowd in the church. Rev. George Zocher then made an address dedicating George to his work in Russia.

George was appointed to join retired Army officer Col. William N. Haskell in Russia to take charge of the distribution of aid contributed by the Volga Relief Society. The Portland Chapter of the Volga Relief Society had raised $18,000. Col. Haskell was in charge of the A.R.A.'s Russian operations and traveled to Russia in early September, according to a report in the New York Times.

George left Portland on September 9, 1921, and traveled to New York, where he filed his passport application on September 14, 1921. According to an article published in The Oregonian on October 4, 1921, George sailed from New York the prior week on the steamship Kroonland bound for London.

On the voyage, George met the former governor of Indiana, James Putnam Goodrich, who was sent to Russia as a personal representative of Herbert Hoover. Governor Goodrich was to send a report directly to Hoover on the situation in Russia. During the 11 days it took to cross the Atlantic, George and Governor Goodrich had many opportunities to talk about the conditions in Russia. As a result of the conversations with George, the Governor developed a keen interest in the Volga Germans.

George left Portland on September 9, 1921, and traveled to New York, where he filed his passport application on September 14, 1921. According to an article published in The Oregonian on October 4, 1921, George sailed from New York the prior week on the steamship Kroonland bound for London.

On the voyage, George met the former governor of Indiana, James Putnam Goodrich, who was sent to Russia as a personal representative of Herbert Hoover. Governor Goodrich was to send a report directly to Hoover on the situation in Russia. During the 11 days it took to cross the Atlantic, George and Governor Goodrich had many opportunities to talk about the conditions in Russia. As a result of the conversations with George, the Governor developed a keen interest in the Volga Germans.

After their arrival in London, George and Governor Goodrich met with the European A.R.A. Chief, Walter Lyman Brown. Brown had recently negotiated with the Russian government for permission for the A.R.A. to work without restrictions in the Volga region. George was asked if he would sign a contract to become a member of the A.R.A. staff. This was a surprise given that George expected to fully cooperate with the A.R.A. but not be one of their staff. It was also a great compliment to George's capabilities and eliminated the need for the Volga Relief Society to pay his expenses as long as he remained in Russia.

Two days after they arrived in London, George and Governor Goodrich departed, traveling from Dover, England, to Ostend, Belgium, and then across Germany to Riga, Latvia, a primary point of entry for foreigners seeking access to the Soviet Union.

On October 4th, the train crossed the border between Latvia and the Soviet Union at Sebesh (Sebezh), and the A.R.A. representative was subjected to a tedious customs interrogation and then was told there was no room for their baggage on the train. To keep their baggage with them, they were forced to pay bribes to the Soviet officials. After the payment of bribes, room for their baggage was miraculously found!

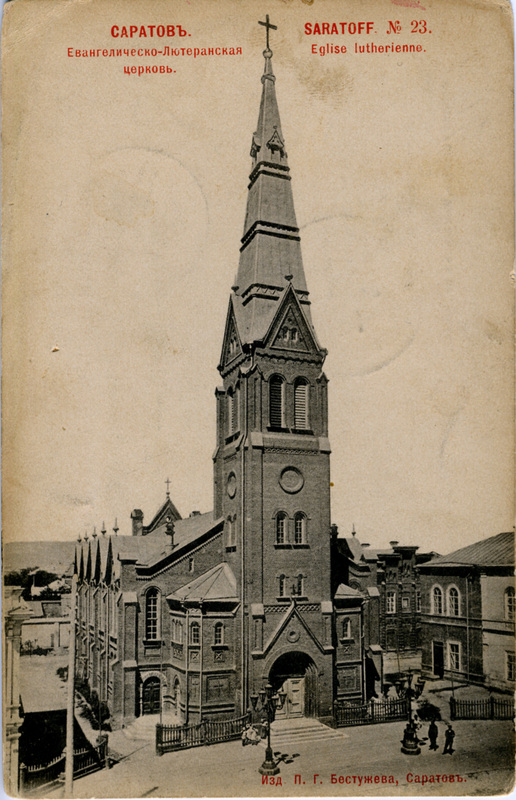

George took a train from Moscow to Samara on October 10th. At that time, kitchens had yet to be opened up for the colonies south of Saratov. George began to hear and read terrible stories about the suffering brought about by the famine, and he was eager to reach the Volga German colonies.

While in Samara, George met with Governor Goodrich and other A.R.A. officials. It was decided that George would depart for Saratov on a Volga steamer. George had to fight a large crowd of peasants who wanted to board the steamer. With the help of a Russian lawyer, he finally convinced the captain to gain access to a cabin. The steamer left Samara at 7 p.m. on October 13th and arrived in Saratov the following day. George later provided the following description of what they saw as they approached the shore:

Two days after they arrived in London, George and Governor Goodrich departed, traveling from Dover, England, to Ostend, Belgium, and then across Germany to Riga, Latvia, a primary point of entry for foreigners seeking access to the Soviet Union.

On October 4th, the train crossed the border between Latvia and the Soviet Union at Sebesh (Sebezh), and the A.R.A. representative was subjected to a tedious customs interrogation and then was told there was no room for their baggage on the train. To keep their baggage with them, they were forced to pay bribes to the Soviet officials. After the payment of bribes, room for their baggage was miraculously found!

George took a train from Moscow to Samara on October 10th. At that time, kitchens had yet to be opened up for the colonies south of Saratov. George began to hear and read terrible stories about the suffering brought about by the famine, and he was eager to reach the Volga German colonies.

While in Samara, George met with Governor Goodrich and other A.R.A. officials. It was decided that George would depart for Saratov on a Volga steamer. George had to fight a large crowd of peasants who wanted to board the steamer. With the help of a Russian lawyer, he finally convinced the captain to gain access to a cabin. The steamer left Samara at 7 p.m. on October 13th and arrived in Saratov the following day. George later provided the following description of what they saw as they approached the shore:

The first thing we saw was from fifteen hundred to two thousand people on the banks of the Volga, without food and in rags, mostly Germans, and all bound for somewhere, none of them knowing really where they wanted to go, but just to get away. Everything they possessed in this world they had with them; a good many were sick from exposure and hunger. They went about the city of Saratov picking up potato peelings, melon rinds, cabbage leaves, and in fact, anything that could be eaten. As fast as they could get transportation, either north or south, east or west, by rail or boat, they left.

George and Governor Goodrich were anxious to visit the colonies on the Bergseite (the western and hilly side of the Volga) and traveled by boat to the port town of Schilling and from there to Balzer, Kutter, Alt Dönhof, and Norka, where George was born.

The men immediately noticed how unusually quiet it was in each village. The ordinary sounds of dogs barking, wagons moving, and children playing were absent. Only a few people could be seen moving listlessly in the villages. Many homes were empty because the families had been killed during the Civil War or they had left to find food.

George reported that since there was no fodder for the horses and livestock, people would remove the thatch from the roofs of the empty houses, knock out the dust, and then give it to the animals for food. The animals remained undernourished as the thatch was 8 to 10 years old.

In each village, George and Goodrich would meet with the officials at the administrative headquarters. They would ask how many people had died that year, the amount of food on hand, and the necessity for American aid. They found in every case that the poorest people in the communities had experienced starvation. George wrote, "It was very evident that 75% of the inhabitants would die before the 1922 harvest unless help came from the outside world. We found them at this time eating horses, camels, dogs, cats, field mice, the bark of trees, and some people that had a little rye flour left would mix this with earth and eat it."

After their return to Saratov, they provided a report on the conditions in the villages. The A.R.A. decided that the area inhabited by the Volga Germans was too large for one man to manage. Paul Clapp was assigned to the east side of the river (the Wiesenseite), and George was assigned to the west side of the river (Bergseite). On October 28th, all available food was loaded on ships and started down the Volga. George went on the boat to Schilling, and Clapp boarded the vessel to Seelman. In a letter to his wife, George described this as one of the happiest days of his life.

While in Saratov, George attended the German Lutheran church and noted the relative good health of the people in the city.

The men immediately noticed how unusually quiet it was in each village. The ordinary sounds of dogs barking, wagons moving, and children playing were absent. Only a few people could be seen moving listlessly in the villages. Many homes were empty because the families had been killed during the Civil War or they had left to find food.

George reported that since there was no fodder for the horses and livestock, people would remove the thatch from the roofs of the empty houses, knock out the dust, and then give it to the animals for food. The animals remained undernourished as the thatch was 8 to 10 years old.

In each village, George and Goodrich would meet with the officials at the administrative headquarters. They would ask how many people had died that year, the amount of food on hand, and the necessity for American aid. They found in every case that the poorest people in the communities had experienced starvation. George wrote, "It was very evident that 75% of the inhabitants would die before the 1922 harvest unless help came from the outside world. We found them at this time eating horses, camels, dogs, cats, field mice, the bark of trees, and some people that had a little rye flour left would mix this with earth and eat it."

After their return to Saratov, they provided a report on the conditions in the villages. The A.R.A. decided that the area inhabited by the Volga Germans was too large for one man to manage. Paul Clapp was assigned to the east side of the river (the Wiesenseite), and George was assigned to the west side of the river (Bergseite). On October 28th, all available food was loaded on ships and started down the Volga. George went on the boat to Schilling, and Clapp boarded the vessel to Seelman. In a letter to his wife, George described this as one of the happiest days of his life.

While in Saratov, George attended the German Lutheran church and noted the relative good health of the people in the city.

George arranged to transport food from Schilling and other river towns to the inland villages. Finding men with horses and wagons who could still work was difficult.

In each town and village, a committee was formed to feed the children and take charge of the kitchen. The committee usually included the Vorsteher (head of the village council), Schreiber (secretary), pastor, and doctor, if there was one. Armed guards were permanently stationed around the warehouses in the harbor towns and interior villages.

The poorest children in the villages were fed first, and it was sometimes difficult to persuade the better-off inhabitants to assist in this task. Still, as a whole, they were glad to serve, even if their families did not directly benefit.

After some delay, the first kitchen opened in Schilling on November 2nd, and about 200 children were chosen from the poorest families. George tells the story of a little boy who asked wistfully, "Uncle, when WILL the kitchens open?" and upon being told that the cooks were a little slow, he suggested, "Let's throw them in the Volga!"

George reached Norka on November 7th and organized a committee of 13 men to organize the kitchen and feeding. The kitchens were set up in the two schoolhouses of the village and the schoolteacher's summer kitchen. Soviet officials saw that wood, water, and utensils were on hand. In three days, enough food had arrived from Schilling to last for six weeks.

There were over 2,000 children in Norka, and only 500 could be fed the day the kitchens opened. According to Pastor Wacker, the most challenging task was to pick out the children who most needed the food. Sometimes, one child in a family would be chosen to receive food while his siblings were not.

There was intense competition among the women in the villages to be cooks, which brought no pay but did bring a double portion of food each day.

On November 14, the three kitchens in Norka opened, and a tremendous chaotic rush of children poured in with an admittance card, a spoon, and a plate.

The experience in Norka was typical for most of the German villages. Repp worked with great speed, and by December 2nd, he reported that they were feeding 9,085 children in 24 villages. Arrangements had been made to open kitchens in the 59 remaining German colonies on the Bergseite, and soon, 30,000 children would be fed.

In a letter to John W. Miller dated February 13, 1922, George reported that they were feeding 35,000 souls on the Bergseite, and by February 24th, they would be feeding 40,000. George also says there will soon be enough food to feed adults.

In addition to feeding the most needy, seed grain was provided in hopes of creating a successful harvest in 1922. Clothing was also provided to the extent possible.

Given that there wasn't enough food or clothing for everyone, and difficult choices had to be made daily, it was inevitable that some would express frustration about the situation. On the 30th of November, Johann Georg and Katharina Feuerstein in Norka wrote a long letter of complaint and sorrow to their brothers-in-law, Ludwig Schwindt and Philipp Scheidemann, who lived in Hastings, Nebraska. Their letter was summarized by the editor of Die Welt Post on March 2, 1922:

In each town and village, a committee was formed to feed the children and take charge of the kitchen. The committee usually included the Vorsteher (head of the village council), Schreiber (secretary), pastor, and doctor, if there was one. Armed guards were permanently stationed around the warehouses in the harbor towns and interior villages.

The poorest children in the villages were fed first, and it was sometimes difficult to persuade the better-off inhabitants to assist in this task. Still, as a whole, they were glad to serve, even if their families did not directly benefit.

After some delay, the first kitchen opened in Schilling on November 2nd, and about 200 children were chosen from the poorest families. George tells the story of a little boy who asked wistfully, "Uncle, when WILL the kitchens open?" and upon being told that the cooks were a little slow, he suggested, "Let's throw them in the Volga!"

George reached Norka on November 7th and organized a committee of 13 men to organize the kitchen and feeding. The kitchens were set up in the two schoolhouses of the village and the schoolteacher's summer kitchen. Soviet officials saw that wood, water, and utensils were on hand. In three days, enough food had arrived from Schilling to last for six weeks.

There were over 2,000 children in Norka, and only 500 could be fed the day the kitchens opened. According to Pastor Wacker, the most challenging task was to pick out the children who most needed the food. Sometimes, one child in a family would be chosen to receive food while his siblings were not.

There was intense competition among the women in the villages to be cooks, which brought no pay but did bring a double portion of food each day.

On November 14, the three kitchens in Norka opened, and a tremendous chaotic rush of children poured in with an admittance card, a spoon, and a plate.

The experience in Norka was typical for most of the German villages. Repp worked with great speed, and by December 2nd, he reported that they were feeding 9,085 children in 24 villages. Arrangements had been made to open kitchens in the 59 remaining German colonies on the Bergseite, and soon, 30,000 children would be fed.

In a letter to John W. Miller dated February 13, 1922, George reported that they were feeding 35,000 souls on the Bergseite, and by February 24th, they would be feeding 40,000. George also says there will soon be enough food to feed adults.

In addition to feeding the most needy, seed grain was provided in hopes of creating a successful harvest in 1922. Clothing was also provided to the extent possible.

Given that there wasn't enough food or clothing for everyone, and difficult choices had to be made daily, it was inevitable that some would express frustration about the situation. On the 30th of November, Johann Georg and Katharina Feuerstein in Norka wrote a long letter of complaint and sorrow to their brothers-in-law, Ludwig Schwindt and Philipp Scheidemann, who lived in Hastings, Nebraska. Their letter was summarized by the editor of Die Welt Post on March 2, 1922:

In 1917 they had written to all their friends but six months later the letters all came back. Since that time they have heard nothing directly from their friends.

Their son Woldemar died in 1914.

Their oldest daughter married schoolmaster David Borgardt from Schwed on the Wiesenseite.

"I labored at the mill," writes Mr. Feuerstein, "but for now the mills are all quiet because there is nothing to mill. Thousands of people walk around like ghosts and die of starvation. The bells toll continuously. Many people are buried without coffins and others lay in the hedges and pathways and are not buried at all.

The emergency is terribly widespread. The people have nothing in them and nothing on them."

One Pud (36 pounds) of Fruit today costs as much as one paid earlier to buy 5,000 Desyatin of land (135,000 acres). One has to have a wagon full of money in order to do anything.

Those who planted potatoes in their backyard gardens, have by most accounts, had them stolen. The people eat only once a day and in spite of this they only have about 2 months of provisions to sustain their lives.

Much has been spoken about foreign aid. George Repp from America spent 2 hours in Norka and promised to open a kitchen to feed the children.

Children sit naked behind the ovens until their raggedy shirts are dry.

They would be happy with that which one formerly fed to the pigs.

Wholemeal Rye bread or Semolina for the production of Beet Soup would nourish them if only they had enough of it.

Similar letters of frustration were lodged against Pastor Wacker, Jacob Volz, and the National Lutheran Council.

Others would express a broader perspective and gratitude for the work done by George, the Volga Relief Society, and the A.R.A. In a letter dated March 15, 1922, Pastor Wacker from Norka wrote:

Others would express a broader perspective and gratitude for the work done by George, the Volga Relief Society, and the A.R.A. In a letter dated March 15, 1922, Pastor Wacker from Norka wrote:

Highly Esteemed and Dear Friends:

Just now, I am able to steal a few moments to follow the urgings of my heart and write to you. In my last letter I wrote about the obstacles and about the challenges of our common work. These obstacles are increasing ever more and more. In truth, I cannot recount all of the battles for it would make your hearts heavy and I will not diminish our friends who are doing Gods Holy work with such fraternal eagerness. You are wholly entitled to learn the naked truth and our dear friend Repp, who is admired by everyone, and who in a few months will return to his homeland and home, will be able to manage this to your satisfaction. I can see it already in my mind, how you will bombard him with questions. With his clear explanations the nebulous misconceptions will be dispelled and the unvarnished truth will paint a picture of reality that will stay in your minds.

A house has two sides that stand in stark contrast to each other. The back always in the shade and the sun-bathed front facade. Today, let me tell you of this latter.

Against the dark unholy background of the present international situation the activities of the American Relief Administration stand out like a bright star. This is also true, on a smaller scale, for the Volga Relief Society. What the former sons and daughters in America did for their old homeland in this terrible time will forever remain unforgotten in these Volga Colonies.

An excerpt from a letter written by Schoolmaster Carl Fritzler from Tscherbakovka (Mühlberg), published in Die Welt Post on April 10, 1924, expresses his gratitude to George and others who helped with the relief efforts:

I will begin my report with warmest thanks to you my dear German brothers in faith, in the name of our village and from me, the deepest and warmest thanks for your faithful and compassionate remembrance of us in your sending over so many loving gifts of food and clothing which we received through your representatives Mr. Repp, Pastor Wagner and Jakob Volz. We are thankful that these representatives came to us with great love. We, who were saved from starving to death will in our lifetime not forget what you dear brethren and your representatives have done for us.

The complaints must have been disheartening to George, but in a letter published on May 24, 1922, in Die Welt-Post, he remains keenly focused on his work while recognizing the dissatisfaction of some:

Balzer, April 18, 1922

Volga Relief Society, Portland, Oregon

My Dear Friends:

The American Relief Administration corn has landed. An enormous amount of this corn has gone to our German people, the Bergseite colonies alone getting 45 carloads with 1,000 pood to the car (note: a pood is equal to about 36 pounds) . I have sent orders to all the colonies, some of which have already got their share and the balance will get theirs soon.

I am expecting a boat load of food for the kitchens very soon. Have wired Saratov and received the answer that as soon as possible it will be sent.

The personal food drafts are coming fast but not enough good has arrived in Saratov to fill them. I have hope that food will come in great quantities soon, so that the food drafts that are now waiting may be taken care of, and the in the meantime, dear friends, do not give up sending more food drafts to your relatives. Keep them coming.

The weather is good, the snow is gone and the roads are almost dry. It is getting quite warm, in fact I believe it gets very hot here in the summer. I am already sunburned.

Advise people that the postal department does not accept "International Coupons." A good many people write their friends to send letters without stamps that they will pay in the United States. That does not work. The postal department either destroys the letters or returns them. Also inform everyone to write the return address on their letters plainly. I address a good many letters for people and many times cannot read the return address in the United States. This is important.

Regarding conditions there isn't much that I can add to what I have already written you. Death is surely reaping a harvest. Over 300 have died in Balzer since January 1st, 1922. The Monday after Easter, 10 people were buried that day in Balzer. the pastors and school teachers are undoubtedly writing you regarding conditions in their colonies, so you can see from their letters just how things are in each colony. A lot of misery, hunger and dissatisfaction on all sides yet. I have been waiting for Rev. Wagner to come from Saratov to take my work over and then I will go to Saratov and handle the balance of the Volga Relief Society fund. I think that will be disposed of quickly as it will amount to about 100,000 pood which doesn't amount to much in this land. We figure everything by the thousand pood.

I have not received any mail in four weeks on account of roads. In fact there are were no roads here. Not a paved block outside of Saratov. My next letter will be from Saratov.

With kindest regards to all,

I am sincerely yours,

George Repp

According to a letter from Pastor Wacker from Norka published in Die Welt-Post on August 24, 1922, George had achieved significant results in a short period under challenging conditions, which saved thousands of lives.

Norka

To: The Volga Relief Society - Portland, Oregon

As our dear friend, Mr. Repp, begins his journey homeward in the next few days, I want to take the opportunity to write a few lines.

I am sending a tabular overview of the aid received by the village of Norka. As you can see from the tables, by far the largest share of aid came to us from the Volga Relief Society, and in particular from our dear Norkans in North America. This fraternal assistance will truly be remembered forever. As I write these lines, already many Norkans (and in other colonies) are eating their first fresh bread. Many could not have made it this far if a gracious God had not awakened your hearts and minds to come to our aid. May the Lord God repay you all the love you have shown us.

Now we are experiencing the new harvest. It promises to be, if not as good as it seemed at first, but (I can report for the Norka Parish) the farmer will have his daily bread. Much depends, certainly, upon how much the government will take in grain taxes. In addition, much will depend upon the general situation. As long as conditions in Europe do not return to normal the best of harvests will do nothing to help Germany and Russia from their untenable situations. Would that it be otherwise.

I hope to write more from time to time. I ask that the enclosed information be sent to the newspapers.

With greetings,

Pastor F. Wacker

______________________________________________

Tabular Overview of the Famine Aid in Norka:

1. Kitchens for Children

From 14 November 1921 to 17 December, 500 children were fed.

From 18 December 1921 to 1 February, 1000 children.

From 5 February to 17 April, 2000 children.

From 6 May to 2 June, 2600 children.

From12 June to 9 July, 2700 children.

From 14 July on, 2765 children.

(At present about 150 children are excluded from admission to the Kitchens as no necessity exists to add them).

Throughout this time, in the 3 Kitchens, the following products were used:

Flour, 2311 Pud 3 Pfund

Rice, 558 Pud 95 Pfund

Grits, 552 Pud 28 Pfund

Beans, 72 Pud 17 Pfund

Cocoa? 95 Pud 27 Pfund

Sugar, 227 Pud 37 Pfund

Lard, 220 Pud 32 Pfund

Milk, 30,298 Pfund cans

(75.23 Pud still retained in accordance with previous instructions).

2. Supplies for Adults

2522 Pud of Maize distributed to 2350 persons from 16 April to 28 May. No vouchers as yet for the 4200 Pud of Maize for the period 29 May to 25 July.

3. General Distribution

Flour, 4171 Pud 2 Pfund

Rice, 629 Pud 30 Pfund

Grits, 2084 Pud 34 Pfund

Sugar, 657 Pud 18 Pfund

Cocoa 219 Pud 14 Pfund

Lard, 343 Pud 18 Pfund

Milk, 54,528 Pfund cans

The Soviet Authorities supplied 400 adults for a period of about 4 months. Also support from Pastor Weigum of Appenzell, Switzerland is expected from Germany.

Rev. Wacker reported a moderate harvest in 1922, which surely eased the immediate famine conditions. Nonetheless, conditions remained difficult in the Volga German colonies for several years. While George must have felt satisfaction in his work, he surely knew that the problems of his countrymen were not entirely resolved. Due to the Civil War and famine, thousands of widows and orphans remained in challenging situations. Adequate clothing was in short supply, and the buildings desperately needed repair.

The National Volga Relief Society continued its work and held a convention in Portland at the Zion German Congregational Church on June 12, 1924. The national officers were all from Lincoln, Nebraska, and included H. J. Amen, President; John Rohrig, First Vice President; Rev. G. J. Schmidt, Secretary; and J. J. Stroh, Treasurer. John W. Miller remained President of the Western Branch of the society. The Oregonian reported that the meetings were held in German. Judge Jacob Kanzler of Portland and Rev. R. Kuehns of Lincoln, Nebraska, addressed the convention, and music was provided by the Zion chorus choir.

In hindsight, it was very fortunate that George happened to leave on the same boat for London as Governor Goodrich, where he developed a personal relationship with him. Based on what Governor Goodrich learned about the Volga German colonies from George, he personally surveyed this area when he arrived. The sympathetic report on the Volga German colonies that Goodrich delivered in New York caused the A.R.A. to take much more interest in this group than they might have otherwise. George's ability to build trust and confidence with the A.R.A. leadership and the community leaders in the Volga German colonies was equally important as his tremendous organizational skills.

At its peak, the A.R.A. employed 300 Americans and more than 120,000 Russians and fed 10.5 million people daily. Despite their heroic efforts, approximately 170,000 men, women, and children died of starvation in the Volga German colonies alone (about one-third of the population, according to Peter Sinner). Without the efforts of the A.R.A., the situation would have been much worse.

The appreciation of the work done by George Repp is expressed in the following letter written by A.R.A. Secretary Herbert Hoover on September 14, 1922.

The National Volga Relief Society continued its work and held a convention in Portland at the Zion German Congregational Church on June 12, 1924. The national officers were all from Lincoln, Nebraska, and included H. J. Amen, President; John Rohrig, First Vice President; Rev. G. J. Schmidt, Secretary; and J. J. Stroh, Treasurer. John W. Miller remained President of the Western Branch of the society. The Oregonian reported that the meetings were held in German. Judge Jacob Kanzler of Portland and Rev. R. Kuehns of Lincoln, Nebraska, addressed the convention, and music was provided by the Zion chorus choir.

In hindsight, it was very fortunate that George happened to leave on the same boat for London as Governor Goodrich, where he developed a personal relationship with him. Based on what Governor Goodrich learned about the Volga German colonies from George, he personally surveyed this area when he arrived. The sympathetic report on the Volga German colonies that Goodrich delivered in New York caused the A.R.A. to take much more interest in this group than they might have otherwise. George's ability to build trust and confidence with the A.R.A. leadership and the community leaders in the Volga German colonies was equally important as his tremendous organizational skills.

At its peak, the A.R.A. employed 300 Americans and more than 120,000 Russians and fed 10.5 million people daily. Despite their heroic efforts, approximately 170,000 men, women, and children died of starvation in the Volga German colonies alone (about one-third of the population, according to Peter Sinner). Without the efforts of the A.R.A., the situation would have been much worse.

The appreciation of the work done by George Repp is expressed in the following letter written by A.R.A. Secretary Herbert Hoover on September 14, 1922.

Dear Mr. Repp:

The German-Russian people both in this country and along the Volga owe you a great debt of gratitude. The American Relief Administration realizes this perhaps more than your own people do, for we have seen the efficiency and devotion displayed in your work at first hand. I should like to express to you both in the name of the A.R.A. and myself, personally, our hearty appreciation and thanks.

Yours faithfully,

Signed Herbert Hoover

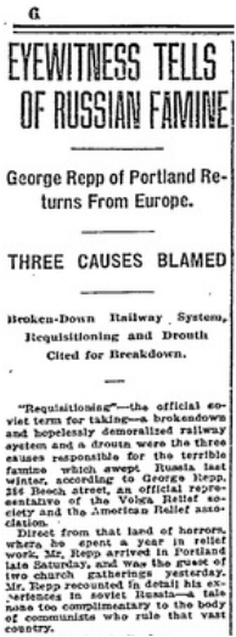

George returned to Portland on Saturday, September 23, 1922, and told his story at the Ebenezer and Zion churches the next day. The following article was published in The Oregonian on Monday, September 25, 1922:

The Volga Relief Society did immeasurable good in the German colonies by feeding 60,000 adults and 75,000 children and distributing medicine, shoes, and warm clothing. The secretaries of the various relief societies state that approximately one-half million dollars were raised by Volga Germans living in the United States and sent to their friends and families through general funds or using food and clothing drafts.

Four years later, when Hoover visited Portland, the following statement appeared in The Oregon Journal on August 23, 1926, under the headline "Hoover seeks Local Hero":

Four years later, when Hoover visited Portland, the following statement appeared in The Oregon Journal on August 23, 1926, under the headline "Hoover seeks Local Hero":

There is one man in Portland that Hoover asked particularly to see again. He is George Repp, proprietor of a butcher shop at No. 774 Union Avenue. 'Repp is of German extraction, but he is really a Russian, or was until he became an American,' Hoover said. 'He left his butcher shop when Russia was in such a bad state and made up a relief fund among his people in this county. It was when the American Relief was extending help to those people of the Volga that Repp came to me in Washington. As soon as I saw his face I sent him right over. Why, those people over there worshipped him like a god. And when his work was done, he came back to his butcher shop.'

Sources

Halliday, E. M. "Bread Upon The Waters." American Heritage 11.5 (1960): n. pag. Web. 5 Feb. 2018. <https://www.americanheritage.com/content/bread-upon-waters>.

Haynes, Emma S. A History of the Volga Relief Society. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1982. Print.

"Millions Starving in Lenin's Paradise of Atheism." The Literary Digest 70 (1921): 32-33. Web. 3 May 2018. <https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015028101486?urlappend=%3Bseq=348>.

Ancestry.com

The Oregonian historical online archive.

Die Welt-Post (a German language newspaper published in the United States).

Correspondence with Fred Luck.

Correspondence with Robert Repp, grandson of Adam Repp.

Haynes, Emma S. A History of the Volga Relief Society. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1982. Print.

"Millions Starving in Lenin's Paradise of Atheism." The Literary Digest 70 (1921): 32-33. Web. 3 May 2018. <https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015028101486?urlappend=%3Bseq=348>.

Ancestry.com

The Oregonian historical online archive.

Die Welt-Post (a German language newspaper published in the United States).

Correspondence with Fred Luck.

Correspondence with Robert Repp, grandson of Adam Repp.

Last updated December 10, 2023