Traditions > Weddings

Weddings

Weddings were known as the Hochzeit (the "high times") and were looked forward to by both young and old. Even the simplest were notable community events.

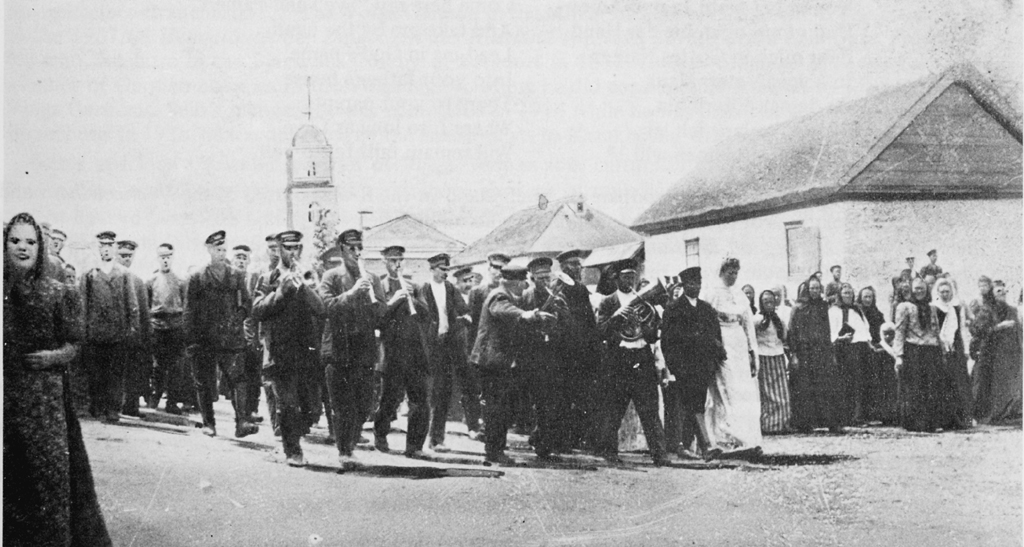

Photograph of the wedding party of Henry and Catherine Elizabeth Lorenz in June or July of 1906. Weddings typically had to wait until the winter time after the crops were harvested and the food was preserved. However, this was a special case. Henry had just returned from Siberia, where he had been wounded in the land battles with the Japanese somewhere along the Yalu River. He was fortunate to have survived his wounds. While he was away his first wife died. This day was also the goodbye celebration for the bride and groom as they would be leaving for America on August 15, 1906 from Saratov and they would not return. Photograph courtesy of Walt Lorenz.

The personal life of the family was under the charge of the church. As a result, the church set the conditions for both marriage and divorce.

Marriage required the voluntary consent of the bride and groom, their parents and from the colonies inspector assigned by the Guardianship Office (known as the Kontora).

From the time of settlement in 1767 to 1830, the legal age of marriage was 15 years for men and 12 years for women. From 1830 forward, the groom was required to be at least 18 years old and the bride 16 years old. However, the evidence shows that some marriages were performed for those younger than the "required" ages. Both government and church rules prohibited marriage by those deemed "mentally ill". Marriage between Christian confessions was allowed (although rare). For many years, marriage between someone of the Russian Orthodox faith and someone of the Lutheran, Reformed, and Catholic faiths was prohibited.

After an appropriate courtship period when the couple had come to a mutual understanding, the young man had to first obtain his father's "approval" to marry. This was usually granted since it meant bringing another worker into the family.

Four more approvals were necessary to proceed with the wedding.

The father of the young woman was not approached by the suitor, but by one or two of his adult relatives or friends, one of whom was his godfather (if available). The matchmakers would set out on their romance inspired mission to the house of the intended father-in-law and engage him in small talk as he pretended not to be aware of what was going to happen next. Then the matchmakers would reveal their true purpose and girl's father would feign his surprise and verbally spar with the matchmakers until his consent was extracted.

At last, the bride-to-be was called into the room by her father to give her consent to the proposal. Of course, she and her mother had been listening to the comic affair from another room. Sometimes the mother would also be asked for her consent. The outcome, known by all parties from the start, was sealed with toasts of vodka and tea along with snacks. One of the emissaries would race his sleigh to the home of the suitor's parents and bring them back to the celebration.

Having won the blessings of both families, it was necessary for the young couple to obtain the approval of the church. This involved a rigorous personal examination of each person by the pastor. If they were found wanting, they were sent home to prepare themselves for another interrogation at a later date. While Confirmation was a prerequisite for marriage, it was still necessary for the candidates to demonstrate their ability by reciting the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, the Lord's Prayer and in explaining the basic principles of their faith. After successfully demonstrating their qualifications to the pastor, the couple was considered to be engaged.

The next step was to set the wedding date. Since only a pastor could officiate, it had to be on date that suited his calendar (many pastors served multiple villages). Since Norka was a parish center, this task would have been much easier.

Many marriages took place during the week between Christmas and the New Year celebration or during another time in the winter when there was no field work and most people were at home in the colony. Groups marriages were not uncommon.

The fourth and final step confronting the engaged couple was proclamation of the banns by the Schulmeister (schoolmaster) at the close of church services on three consecutive Sundays. In urgent cases, this step could be fulfilled by reading the banns three times at the same church service.

Marriage practices varied depending on the piety and financial situation of the bride groom's and bride's parents.

The ceremony could be a subdued family affair (with no dancing or music) at the home of the groom and concluded on a Sunday evening. This type of wedding was common if parents were members of the Brethren, which was common in Norka.

Other weddings involved large numbers of guests with three days of dancing, toasting, singing, snacking, and entertainment. The bride and groom could be escorted from the church or place of marriage to the bride's new home, sometimes preceded by musicians. Band members were compensated by wedding guest donations. Some elaborate weddings were said to outshine the Kerb celebrations.

Marriage required the voluntary consent of the bride and groom, their parents and from the colonies inspector assigned by the Guardianship Office (known as the Kontora).

From the time of settlement in 1767 to 1830, the legal age of marriage was 15 years for men and 12 years for women. From 1830 forward, the groom was required to be at least 18 years old and the bride 16 years old. However, the evidence shows that some marriages were performed for those younger than the "required" ages. Both government and church rules prohibited marriage by those deemed "mentally ill". Marriage between Christian confessions was allowed (although rare). For many years, marriage between someone of the Russian Orthodox faith and someone of the Lutheran, Reformed, and Catholic faiths was prohibited.

After an appropriate courtship period when the couple had come to a mutual understanding, the young man had to first obtain his father's "approval" to marry. This was usually granted since it meant bringing another worker into the family.

Four more approvals were necessary to proceed with the wedding.

The father of the young woman was not approached by the suitor, but by one or two of his adult relatives or friends, one of whom was his godfather (if available). The matchmakers would set out on their romance inspired mission to the house of the intended father-in-law and engage him in small talk as he pretended not to be aware of what was going to happen next. Then the matchmakers would reveal their true purpose and girl's father would feign his surprise and verbally spar with the matchmakers until his consent was extracted.

At last, the bride-to-be was called into the room by her father to give her consent to the proposal. Of course, she and her mother had been listening to the comic affair from another room. Sometimes the mother would also be asked for her consent. The outcome, known by all parties from the start, was sealed with toasts of vodka and tea along with snacks. One of the emissaries would race his sleigh to the home of the suitor's parents and bring them back to the celebration.

Having won the blessings of both families, it was necessary for the young couple to obtain the approval of the church. This involved a rigorous personal examination of each person by the pastor. If they were found wanting, they were sent home to prepare themselves for another interrogation at a later date. While Confirmation was a prerequisite for marriage, it was still necessary for the candidates to demonstrate their ability by reciting the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, the Lord's Prayer and in explaining the basic principles of their faith. After successfully demonstrating their qualifications to the pastor, the couple was considered to be engaged.

The next step was to set the wedding date. Since only a pastor could officiate, it had to be on date that suited his calendar (many pastors served multiple villages). Since Norka was a parish center, this task would have been much easier.

Many marriages took place during the week between Christmas and the New Year celebration or during another time in the winter when there was no field work and most people were at home in the colony. Groups marriages were not uncommon.

The fourth and final step confronting the engaged couple was proclamation of the banns by the Schulmeister (schoolmaster) at the close of church services on three consecutive Sundays. In urgent cases, this step could be fulfilled by reading the banns three times at the same church service.

Marriage practices varied depending on the piety and financial situation of the bride groom's and bride's parents.

The ceremony could be a subdued family affair (with no dancing or music) at the home of the groom and concluded on a Sunday evening. This type of wedding was common if parents were members of the Brethren, which was common in Norka.

Other weddings involved large numbers of guests with three days of dancing, toasting, singing, snacking, and entertainment. The bride and groom could be escorted from the church or place of marriage to the bride's new home, sometimes preceded by musicians. Band members were compensated by wedding guest donations. Some elaborate weddings were said to outshine the Kerb celebrations.

If a widow with children remarried outside of the village, she was allowed to take her young unmarried daughters with her. If she had young sons, they remained in the village with the grandparents who would raise them. This arrangement was common since farmland for each colony was allotted based on the number of males in each household.

Marriages between Germans and Russians were extremely rare until the deportation in 1941.

Marriages between Germans and Russians were extremely rare until the deportation in 1941.

According to Christian doctrine, only death could terminate a marriage. However, the Lutheran church could dissolve a marriage if: 1) the spouse was absent for 5 years without an obvious reason; 2) one spouse had an incurable disease; 3) one spouse engaged in heavy drinking, abuse, beatings, or violent behavior; 4) one spouse committed a serious crime.

Polygamy was strictly prohibited. Adultery was also prohibited and violators were punished by church. The typical punishment required the guilty party to stand before the congregation during the church service on a special raised platform that was painted black. The pastor addressed the sinner with a personal sermon. After a prayer, the sinner was not allowed to take Holy Communion and was banned from the church for a specified period of time (typically several weeks to several months). When the sinner returned to church, they were required to publicly repent and confess their sins. In addition, the church could impose financial penalties on the adulterer. In 1861, the Kontora banned the assessment of fines arguing that they were "humiliating to a human being's dignity".

Premarital sex and pregnancy were prohibited, but the parish records shows that these natural activities occurred somewhat regularly. The punishment was generally not strict, and the couple typically married to legitimize the birth of their child.

Polygamy was strictly prohibited. Adultery was also prohibited and violators were punished by church. The typical punishment required the guilty party to stand before the congregation during the church service on a special raised platform that was painted black. The pastor addressed the sinner with a personal sermon. After a prayer, the sinner was not allowed to take Holy Communion and was banned from the church for a specified period of time (typically several weeks to several months). When the sinner returned to church, they were required to publicly repent and confess their sins. In addition, the church could impose financial penalties on the adulterer. In 1861, the Kontora banned the assessment of fines arguing that they were "humiliating to a human being's dignity".

Premarital sex and pregnancy were prohibited, but the parish records shows that these natural activities occurred somewhat regularly. The punishment was generally not strict, and the couple typically married to legitimize the birth of their child.

Sources

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 189-191. Print.

Burbach, William. Norka Wedding Customs.

Litzenberger, Olga C. "German Lutherans and Catholics: Settling, Population Changes, Peculiarities of Integration and Adaptation". Usu Leut vo Jagada, Vol. 33 No. 3. September 2018.

Burbach, William. Norka Wedding Customs.

Litzenberger, Olga C. "German Lutherans and Catholics: Settling, Population Changes, Peculiarities of Integration and Adaptation". Usu Leut vo Jagada, Vol. 33 No. 3. September 2018.

Last updated July 4, 2020.