History > Origins of the Colonists

Origins of the Colonists

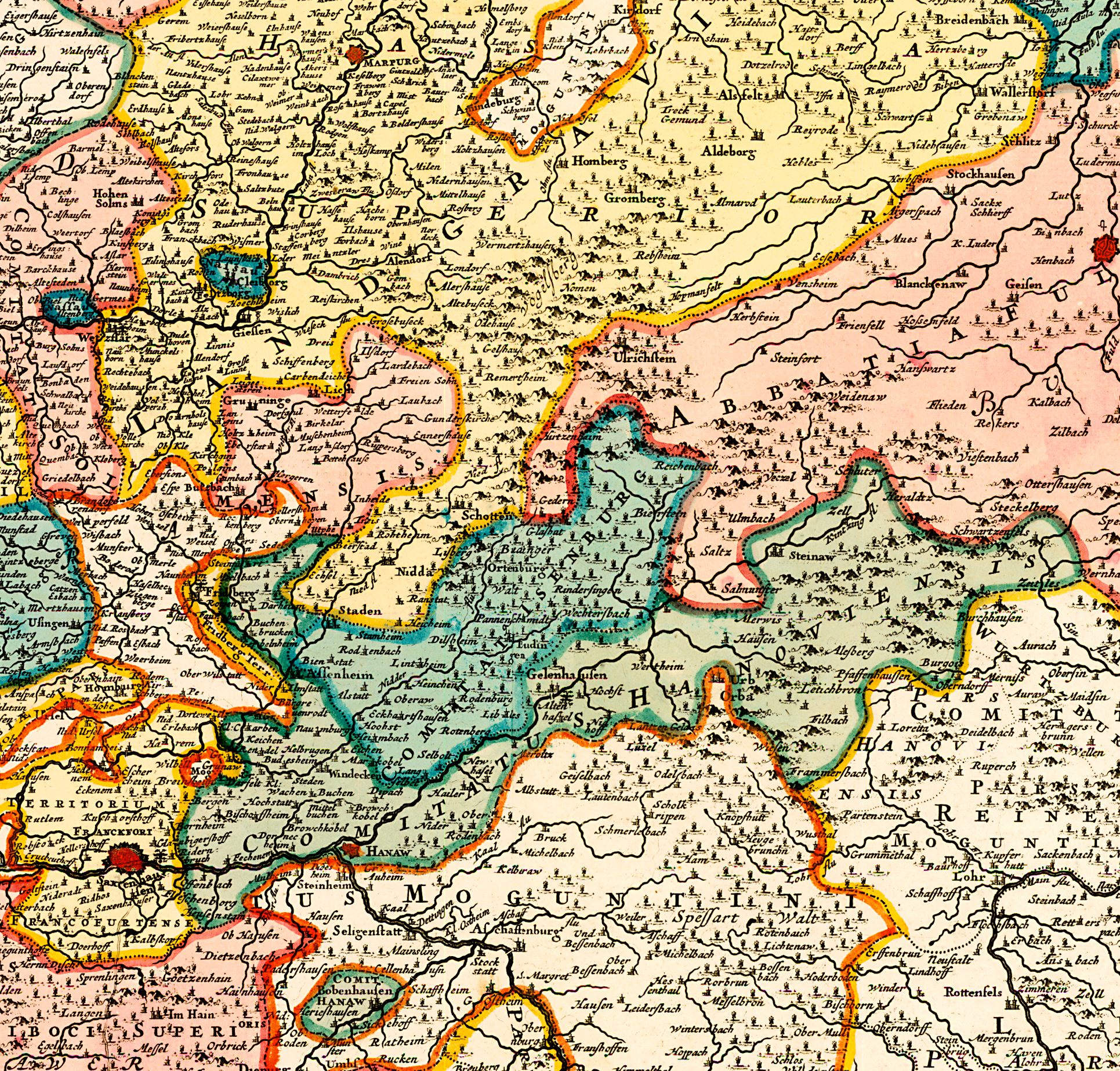

Most colonists who settled in the German colony of Norka originated in the heart of Germany. Many had lived in Grafschaft Ysenburg (the County of Isenburg) and the Landgraviates of Hessen (the Principalities of Hessen).

This part of Germany is rich in history. The region was settled by the Germanic Chatti tribe (also known as the Hessi or by their Latin name Hassia) around the first century BC. The name Hesse is a phonetic variation of their tribal name. The Chatti were described through the firsthand experiences of Julius Caesar and later by Tacitus, a Roman senator and historian, in his ethnographic work titled Germania. The Chatti successfully resisted occupation by the Roman Empire and, along with the Cherusci tribe, defeated Publius Quinctilius Varus and his three legions at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.

This part of Germany is rich in history. The region was settled by the Germanic Chatti tribe (also known as the Hessi or by their Latin name Hassia) around the first century BC. The name Hesse is a phonetic variation of their tribal name. The Chatti were described through the firsthand experiences of Julius Caesar and later by Tacitus, a Roman senator and historian, in his ethnographic work titled Germania. The Chatti successfully resisted occupation by the Roman Empire and, along with the Cherusci tribe, defeated Publius Quinctilius Varus and his three legions at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.

In the 8th century, St. Boniface arrived in Germany and established the Benedictine Monastery of Fulda to convert the pagan tribes from their Germanic deities to Christianity. Legend says that St. Boniface cut down the sacred Donar's Oak of the Chatti to build a church in honor of St. Peter, thereby demonstrating the power of the Christian God over the pagan German gods. Many pagan German customs were blended into Christian holidays such as Easter and Christmas and have become worldwide icons, such as the Easter Rabbit and the Christmas Tree.

Johannes Gutenberg revolutionized the world by inventing the movable type printing press around 1450 in Mainz. Johann Sebastian Bach was born in nearby Eisenach. Martin Luther translated the Bible into German in the same city and had it printed for all to read on Gutenberg's presses. Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the famous German writer and statesman, was born in the nearby Free City of Frankfurt in 1749. The Brothers Grimm, born in Hanau, collected much of their now-famous German folklore in this part of Germany.

Both Isenburg and Hessen were members of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, founded by Charlemagne (his German name was Karl die Grosse) in 800. The Holy Roman Empire grew into a complex multi-ethnic association of political entities, including principalities, counties, free cities, ecclesiastical states, various estates, and other kingdoms ruled by a Catholic Emperor in Vienna. Germany did not exist as a unified nation until 1871, over 100 years after the Volga German colonists departed from these lands.

Johannes Gutenberg revolutionized the world by inventing the movable type printing press around 1450 in Mainz. Johann Sebastian Bach was born in nearby Eisenach. Martin Luther translated the Bible into German in the same city and had it printed for all to read on Gutenberg's presses. Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the famous German writer and statesman, was born in the nearby Free City of Frankfurt in 1749. The Brothers Grimm, born in Hanau, collected much of their now-famous German folklore in this part of Germany.

Both Isenburg and Hessen were members of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, founded by Charlemagne (his German name was Karl die Grosse) in 800. The Holy Roman Empire grew into a complex multi-ethnic association of political entities, including principalities, counties, free cities, ecclesiastical states, various estates, and other kingdoms ruled by a Catholic Emperor in Vienna. Germany did not exist as a unified nation until 1871, over 100 years after the Volga German colonists departed from these lands.

The lands within the Holy Roman Empire were ruled by aristocratic families that were often interrelated by marriage and political affiliation. Each jurisdiction could have its own laws and currency. The nobility felt empowered by divine right to exert a great deal of control over almost every aspect of their subject's lives, including their ability to emigrate to another part of the empire or another nation.

The House of Hesse was founded in 1264 when it separated from the western part of Thuringia as a distinct political entity. In 1567, Hesse was partitioned among the four sons of Landgrave Philip I ("the Magnanimous"). Hesse-Kassel went to the eldest son, William IV ("the Wise). Hesse-Kassel was the largest, most important, and most northerly of the four Hesse landgraviates. William IV introduced sound financial management and a peaceful foreign policy. Under his successors, Hesse-Kassel became Calvinist (the Reformed faith) and fought on the side of the Swedes in the Thirty Years’ War and on the side of Great Britain in the Seven Years’ War. Hesse-Darmstadt was given to the youngest son, George I, and he received the Hessian lands in the former upper County of Katzenelnbogen. The second son, Louis IV, obtained Hesse-Marburg, and the third son, Philipp II, became Landgrave of Hesse-Rheinfels, which went extinct upon his death in 1583. There were further subdivisions of the partitions over time.

The County of Isenburg was founded by an old aristocratic family of medieval Germany, the House of Isenburg. The name Isenburg was adapted from their place of origin, "the Iron Castle" (Eisenburg), which was built in a valley near the Rhine River around 1100. During the Middle Ages, descendants of this family established a new territory around the Büdingen Imperial Forest, which was declared the County of Isenburg and Büdingen by the Holy Roman Emperor in 1442. The town of Büdingen dates from around the year 700, when the wooden church of St. Remigius was built by an unknown lord.

In 1766, the County of Isenburg was divided into four partitions named after the residences at Birstein, Büdingen, Wachtersbach, and Meerholz. Each partition had a castle with its own administration. The Counts of Birstein were Catholic, and the other Counts were Protestant. The Isenburg-Birstein family was distantly related to Catherine the Great, a former German princess.

The House of Hesse was founded in 1264 when it separated from the western part of Thuringia as a distinct political entity. In 1567, Hesse was partitioned among the four sons of Landgrave Philip I ("the Magnanimous"). Hesse-Kassel went to the eldest son, William IV ("the Wise). Hesse-Kassel was the largest, most important, and most northerly of the four Hesse landgraviates. William IV introduced sound financial management and a peaceful foreign policy. Under his successors, Hesse-Kassel became Calvinist (the Reformed faith) and fought on the side of the Swedes in the Thirty Years’ War and on the side of Great Britain in the Seven Years’ War. Hesse-Darmstadt was given to the youngest son, George I, and he received the Hessian lands in the former upper County of Katzenelnbogen. The second son, Louis IV, obtained Hesse-Marburg, and the third son, Philipp II, became Landgrave of Hesse-Rheinfels, which went extinct upon his death in 1583. There were further subdivisions of the partitions over time.

The County of Isenburg was founded by an old aristocratic family of medieval Germany, the House of Isenburg. The name Isenburg was adapted from their place of origin, "the Iron Castle" (Eisenburg), which was built in a valley near the Rhine River around 1100. During the Middle Ages, descendants of this family established a new territory around the Büdingen Imperial Forest, which was declared the County of Isenburg and Büdingen by the Holy Roman Emperor in 1442. The town of Büdingen dates from around the year 700, when the wooden church of St. Remigius was built by an unknown lord.

In 1766, the County of Isenburg was divided into four partitions named after the residences at Birstein, Büdingen, Wachtersbach, and Meerholz. Each partition had a castle with its own administration. The Counts of Birstein were Catholic, and the other Counts were Protestant. The Isenburg-Birstein family was distantly related to Catherine the Great, a former German princess.

While people from Hessen and Isenburg comprised the vast majority of the colonists that settled in Norka, there were also colonists from Hanau, Stolberg, Saxony, Fulda, Kurpfalz, Zweibrücken, France, and the cities of Mainz and Frankfurt.

View a historical map of these former states overlaid on a modern map (David Rumsey Collection)

View a historical map of these former states overlaid on a modern map (David Rumsey Collection)

Norka colonist Johann Wilhelm Schreiber lived in this house in Ronshausen, Germany before his departure to Russia in 1766. His family owned a sawmill and were master carpenters. This photo was taken in 1908 when the house and water powered sawmill were owned by the Fend family. Konrad Fend continues to operate the sawmill as of May 2016. Courtesy of Heinrich Tann (Ronshausen).

The Protestant Reformation, triggered by Martin Luther in 1517, fractured the Holy Roman Empire (and much of Europe) along religious and political lines. The resulting turmoil brought death and devastation to both Isenburg and Hessen during the Thirty Years' War, which was waged from 1618 to 1648. The war began as a conflict between Protestants and Catholics and gradually evolved into a battle over power in Europe between the Holy Roman Empire and France. The Emperor's control of his territories was limited as there were hundreds of kingdoms, electorates, duchies, principalities, counties, city-states, and smaller jurisdictions. Each sovereign area was led by its own ruler, who may or may not have been loyal to the Catholic Emperor.

Residents in Isenburg and Hessen were devastated not only by the conflict but also by the numerous crop failures, famines, and epidemics that accompanied it. The war resulted in widespread political, economic, and social dysfunction. Many were quick to attribute these calamities to supernatural causes. Between 1532 and 1699 (peaking in 1633-1653), 485 people (men and women) were indicted for alleged witchcraft. With over 400 executions, Isenburg-Büdingen was at the center of witch trials in Central Europe.

Among the long-lasting effects of the Thirty Years' War was the rearrangement of European power and an increased independence for the multitude of states that comprised the Holy Roman Empire.

Residents in Isenburg and Hessen were devastated not only by the conflict but also by the numerous crop failures, famines, and epidemics that accompanied it. The war resulted in widespread political, economic, and social dysfunction. Many were quick to attribute these calamities to supernatural causes. Between 1532 and 1699 (peaking in 1633-1653), 485 people (men and women) were indicted for alleged witchcraft. With over 400 executions, Isenburg-Büdingen was at the center of witch trials in Central Europe.

Among the long-lasting effects of the Thirty Years' War was the rearrangement of European power and an increased independence for the multitude of states that comprised the Holy Roman Empire.

Peace in Europe was again shattered in 1756 by the Seven Years' War. It was primarily a battle for European and global powers between Great Britain (and its ally Prussia) and France (with its allies Russia and the Emperor in Vienna). All of the adults who founded Norka lived through this war. Men from Hessen-Kassel served with both the British-Hanoverian and Prussian armies against France. Much of the war was fought within the German states, but it expanded into a global conflict known as the French and Indian War in North America. This so-called "first world war" resulted in 900,000 to 1,400,000 deaths and created social, political, and economic chaos throughout the empire. Despite the scale of the conflict, there were no significant battles in the southern parts of Hessen-Kassel or Isenburg. As a result, death and destruction were absent in these areas. However, many fathers and sons of Hessen-Kassel were injured or killed in the conflict. Those fortunate enough to survive would surely have brought home the stories of this horrific war.

After the war ended in 1763, the population in central Europe began to recover, and farmland was again in short supply. Poor harvests in the early 1760s drove up food prices, and shortages became prevalent. Many families lived on the edge of existence and had little prospect of a stable life. It was a difficult time, especially for the landless lower classes. The only social safety net at this time was family. If a person fell into debt and poverty, they had to rely on family or charity from others. As a last resort, desperate people had to take matters into their own hands. Many people in Isenburg and Hessen wanted a better life, even if that meant leaving their homeland.

The timing and appeal of Catherine II's Manifesto in 1763 could not have come at a better time. The Russian government's promises of free land, freedom of religion, the right of self-government, exemption from taxation for 30 years, and exemption from military service in perpetuity must have seemed like a godsend. While there were risks to be considered, migration to Russia offered many hope for a better life.

Recruitment of colonists began shortly after the publication of Catherine's Manifesto, and one of the primary headquarters was established in Isenburg-Büdingen.

The timing and appeal of Catherine II's Manifesto in 1763 could not have come at a better time. The Russian government's promises of free land, freedom of religion, the right of self-government, exemption from taxation for 30 years, and exemption from military service in perpetuity must have seemed like a godsend. While there were risks to be considered, migration to Russia offered many hope for a better life.

Recruitment of colonists began shortly after the publication of Catherine's Manifesto, and one of the primary headquarters was established in Isenburg-Büdingen.

Sources

Bonwetsch, Gerhard. Geschichte Der Deutschen Kolonien an Der Wolga. Stuttgart: J. Engelhorns Nachf., 1919. 26. Print.

Clunn, Tony. The Quest for the Lost Roman Legions: Discovering the Varus Battlefield. New York: Savas Beatie, 2005. Print.

Decker, Klaus-Peter. Büdingen Als Sammelplatz Der Auswanderung an Die Wolga 1766. Büdingen: Geschichtswerkstatt Büdingen, 2009. Print.

Decker, Klaus-Peter. "Büdingen in the County of Ysenburg as a Recruitment and Gathering Place of the Russian Emigration." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 24.2 (2001): 9-15.

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Printed by Augstums Printing Service, 2005. Print.

MacGregor, Neil. Germany: Memories of a Nation. London: Penguin, 2016. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan, and Dona B. Reeves-Marquardt. German Migration to the Russian Volga (1764-1767): Origins and Destinations. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2003. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Pleve, I. R. Lists of Colonists to Russia in 1766: Reports by Ivan Kulberg. Saratov, Russia: Saratov State Technical U, 2010. Print.

Tacitus, Cornelius, and J. B. Rives. Germania. Oxford: Clarendon, 1999. Print. Public domain audio recording by LibriVox.

Williams, Hattie Plum. The Czar's Germans: With Particular Reference to the Volga Germans. Ed. Emma S. Haynes, Phillip B. Legler, and Gerda Stroh. Walker. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1975. Print.

Clunn, Tony. The Quest for the Lost Roman Legions: Discovering the Varus Battlefield. New York: Savas Beatie, 2005. Print.

Decker, Klaus-Peter. Büdingen Als Sammelplatz Der Auswanderung an Die Wolga 1766. Büdingen: Geschichtswerkstatt Büdingen, 2009. Print.

Decker, Klaus-Peter. "Büdingen in the County of Ysenburg as a Recruitment and Gathering Place of the Russian Emigration." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 24.2 (2001): 9-15.

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Printed by Augstums Printing Service, 2005. Print.

MacGregor, Neil. Germany: Memories of a Nation. London: Penguin, 2016. Print.

Mai, Brent Alan, and Dona B. Reeves-Marquardt. German Migration to the Russian Volga (1764-1767): Origins and Destinations. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2003. Print.

Pleve, I. R., and Richard R. Rye. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. Print.

Pleve, I. R. Lists of Colonists to Russia in 1766: Reports by Ivan Kulberg. Saratov, Russia: Saratov State Technical U, 2010. Print.

Tacitus, Cornelius, and J. B. Rives. Germania. Oxford: Clarendon, 1999. Print. Public domain audio recording by LibriVox.

Williams, Hattie Plum. The Czar's Germans: With Particular Reference to the Volga Germans. Ed. Emma S. Haynes, Phillip B. Legler, and Gerda Stroh. Walker. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1975. Print.

Last updated November 19, 2023