Religion > Church Planning and History

Church Planning and History

Catherine's Manifesto of 1763 promised religious freedom for the colonists, and the Russian government took this promise seriously.

Through a government decree on January 31, 1764 (Comp. Coll. Of Laws, No. 12322), it was ordered:

Through a government decree on January 31, 1764 (Comp. Coll. Of Laws, No. 12322), it was ordered:

To build in every settled district one church complete with all necessary furnishings and a suitable home for the pastor, at the treasury expense for the inhabitants of the entire district, exempting those expenses for the course of the privileged years from each household at an equal number.

The Russian government believed that this provision of the Manifesto was necessary because the colonists, "in view of their poverty, are not in a position to construct them." The cost of constructing the churches was added to the colonist's debt, which was to be repaid after 10 years of settlement.

By decree of the Governing Senate on May 14, 1767, surveyors were instructed to set aside land for each church at 609 desyatina (a Russian measure of land where 1 desyatina equals roughly 1.1 hectares).

To this purpose, Count Orlov brought together a team of 24 experts from the Cadet-Engineers and Artillery Corps of the army under the leadership of Colonel Ivan (Johann) Reis, a man of noble rank and a collegial assessor. In those days, the army performed the state’s civil engineering projects. All of those selected were expert land surveyors and geodetic surveyors.

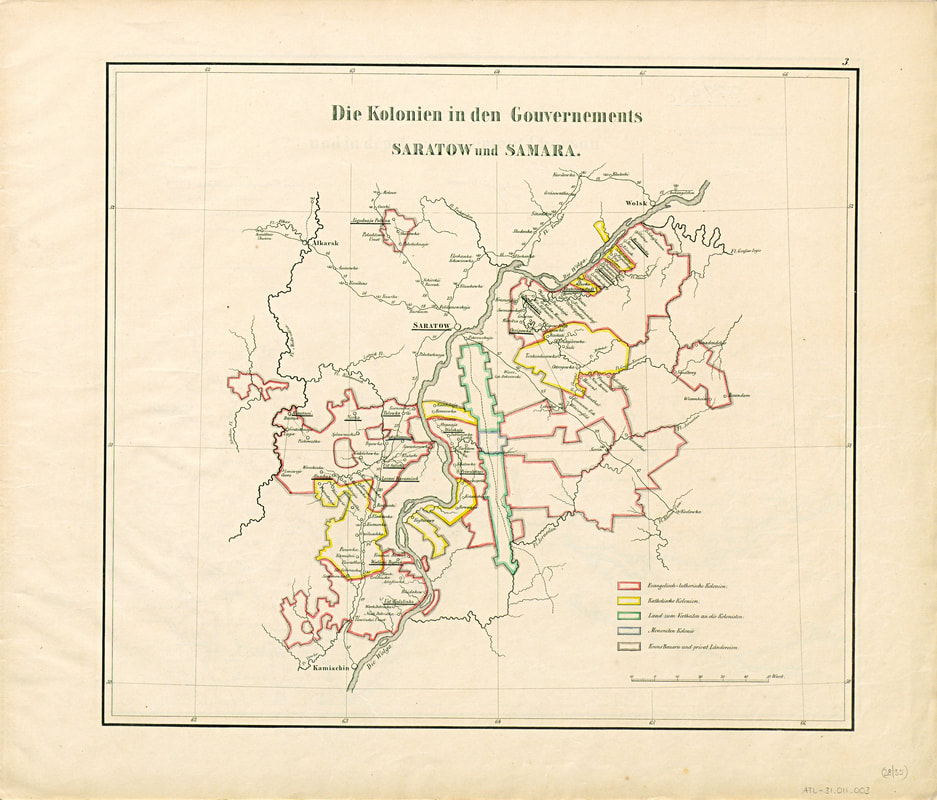

To avoid repeating the religious conflicts of central Europe that had plagued most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Volga German colonists were assigned to colonies mainly based on their religious affiliation. As a result, the colonies were made up primarily or exclusively of one of three religious groups: Evangelical (what we today call Lutheran), Reformed, and Roman Catholic. A few Mennonite colonies were established in the Volga settlement area near Samara in the late 1840s.

The church was under the complete control of the Saratov Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers, known as the Kontora, until 1782. After this time, it remained under the control of provincial authorities until the church was abolished entirely in the late 1930s during Stalin's rule.

In the early years after the founding of the original colonies, there were sixteen churches, and their schools and pastors' homes were based on the number of parishes: eleven Protestant and five Catholic. The first Protestant parishes were established in 1767: Talovka (Beideck), Lesnoi Karamysh (Grimm), Podstepnaya (Rosenheim), and Sevastjanovka (Anton). Ust-Kulalinka (Galka), Medveditskii Krestovyi Buyerak (Frank), DeBoff (in Oleshnya or Dietel), Norka, and Beauregard (in Katharinenstadt) were established in 1768. LeRoy (in Privalnaya or Warenburg) was established in 1770, and Vodyanoi Buyerak (Stephan) was established in 1771. Catholic churches were established in Tonkoshurovka (Mariental) and Kozitskaya (Brabander) in 1767. Kamenka and Krasnopolye (Preuss) in 1768 and Paninskaya (Schönchen) in 1770.

Igor Pleve cites documentation of 19 parishes established by the Kontora in 1777: 9 Lutheran, 3 Reformed, and 7 Catholic.

During the early years of settlement in Russia, the Volga Germans lacked pastors to serve the colonies. Despite the great preponderance of Protestants, few pastors came or stayed with the colonists due to the meager salaries of the clergy who were faced with ministering to scattered parishes, often numbering over 2,000 souls. In the 1798 Russian Census, Court Councilor Popov describes the colony of Warenburg and states that while the Lutheran families had their own pastor, the Reformed faith families did not belong to any parish. Still, when necessary, they called upon the pastor from Norka. The lack of pastors continued to be an acute problem. By 1805, there were only fifteen Protestant pastors in the entire colonial enclave, these living in Messer, Grimm, Beideck, Galka, Dietel, Frank, Norka, Stephan, Yagodnaya Polyana, Saratov, Rosenheim, Warenburg, Bettinger and two in Katharinenstadt. Protestant seminaries were eventually built to give students a better chance of studying closer to home. Despite this fact, shortages persisted and up to 1910, there were between three to five colonies in a Kirchenspiel (parish).

Adam Giesinger wrote, "It was difficult to attract Protestant pastors to the Volga in the early years, and even more difficult to hold them there." Giesinger goes on to say, "As life became more bearable in the Volga colonies the number of Protestant pastors who came to stay gradually increased." "It appears there were few outstanding men among the pastors who served in the Volga colonies during the first 50 years. Three of them, however, Janet, Cattaneo, and Huber, all Reformed, seem to have been above the ordinary." All of these men were trained in Switzerland.

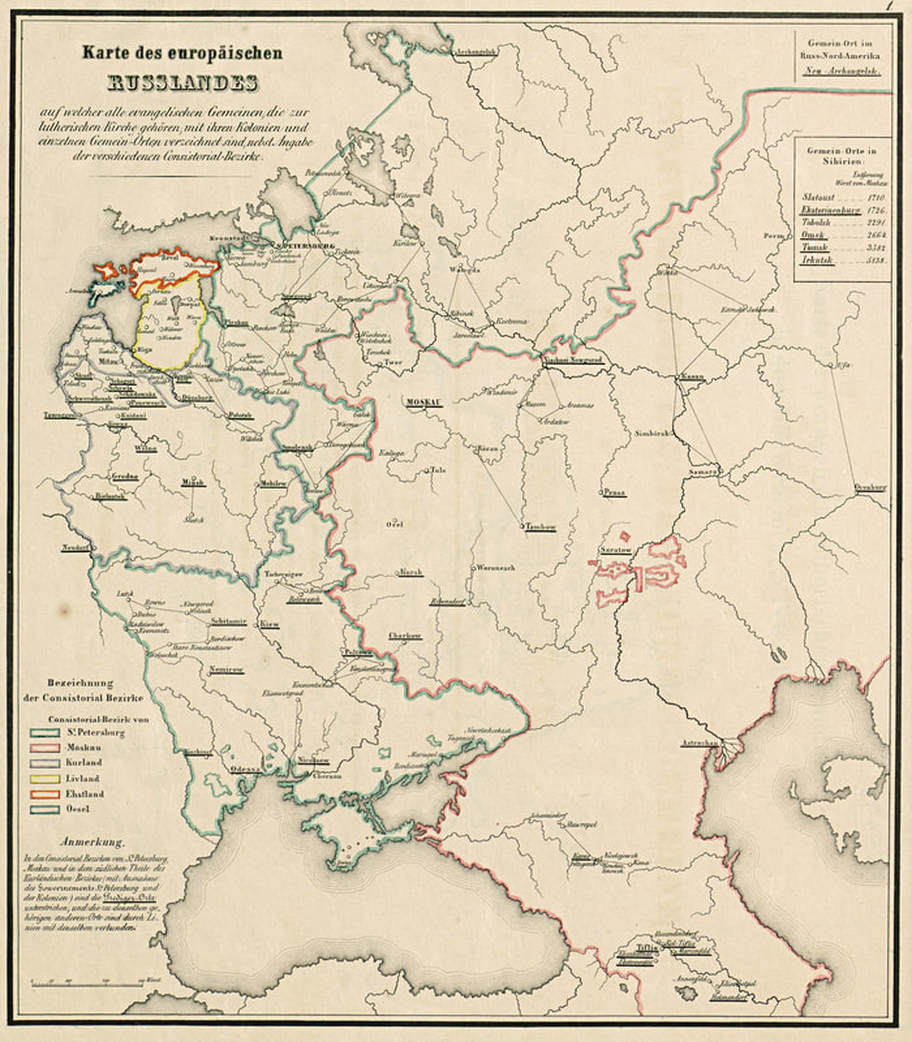

The University of Dorpat (now the University of Tartu) in Estonia was the nearest theological school, but the great distance and expense virtually prevented enrollment by eligible Volga German men.

James Long provides a brief history of the early church leadership and efforts to reconcile the Lutheran and Reformed faiths: "In 1819 (July 20th), the government (of Czar Alexander I) attempted to erase, if not reconcile, differences between Lutherans and Calvinists (Reformed) by placing all Volga German Protestant parishes under the jurisdiction of the newly established Protestant Consistory in Saratov. Under the energetic leadership of a former priest and orientalist, Ignatius Fessler, the differences in the practices and liturgy of the two denominations narrowed as a common hymnal and liturgical manuals were adopted, and annual synods convened to discuss church affairs and to resolve problems. The Reformed Church had become so administratively integrated within the Lutheran parishes, and the two denominations' liturgical differences were so inconsequential that by decree in 1832, the consistory was renamed Lutheran and incorporated into the distant Moscow Lutheran Consistory (later called the National Church Council), which supervised congregations in various parts of the empire." The Moscow Consistory was responsible for inspecting the schools and churches and presiding over the annual synods of the pastors. With the passing of this decree, the Evangelical-Lutheran Church became a state church, just as the Orthodox church was. The Evangelical-Lutheran Church incorporated all Protestants in Russia, including Germans, Latvians, Estonians, and Finns. Until 1917, all the leaders of the church were Germans. The theological faculty in Dorpat (Estonia) was German, and the church's official language was German.

Specific tasks were undertaken by the "Benevolent Fund for Evangelical-Lutheran Churches in Russia," established in 1858. This organization made provisions for dependents of deceased pastors, financed the appointments of incumbents for poor churches, built churches and schools, provided theological training for colonist's sons, and established new parishes.

To this purpose, Count Orlov brought together a team of 24 experts from the Cadet-Engineers and Artillery Corps of the army under the leadership of Colonel Ivan (Johann) Reis, a man of noble rank and a collegial assessor. In those days, the army performed the state’s civil engineering projects. All of those selected were expert land surveyors and geodetic surveyors.

To avoid repeating the religious conflicts of central Europe that had plagued most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Volga German colonists were assigned to colonies mainly based on their religious affiliation. As a result, the colonies were made up primarily or exclusively of one of three religious groups: Evangelical (what we today call Lutheran), Reformed, and Roman Catholic. A few Mennonite colonies were established in the Volga settlement area near Samara in the late 1840s.

The church was under the complete control of the Saratov Office for the Guardianship of Foreign Settlers, known as the Kontora, until 1782. After this time, it remained under the control of provincial authorities until the church was abolished entirely in the late 1930s during Stalin's rule.

In the early years after the founding of the original colonies, there were sixteen churches, and their schools and pastors' homes were based on the number of parishes: eleven Protestant and five Catholic. The first Protestant parishes were established in 1767: Talovka (Beideck), Lesnoi Karamysh (Grimm), Podstepnaya (Rosenheim), and Sevastjanovka (Anton). Ust-Kulalinka (Galka), Medveditskii Krestovyi Buyerak (Frank), DeBoff (in Oleshnya or Dietel), Norka, and Beauregard (in Katharinenstadt) were established in 1768. LeRoy (in Privalnaya or Warenburg) was established in 1770, and Vodyanoi Buyerak (Stephan) was established in 1771. Catholic churches were established in Tonkoshurovka (Mariental) and Kozitskaya (Brabander) in 1767. Kamenka and Krasnopolye (Preuss) in 1768 and Paninskaya (Schönchen) in 1770.

Igor Pleve cites documentation of 19 parishes established by the Kontora in 1777: 9 Lutheran, 3 Reformed, and 7 Catholic.

During the early years of settlement in Russia, the Volga Germans lacked pastors to serve the colonies. Despite the great preponderance of Protestants, few pastors came or stayed with the colonists due to the meager salaries of the clergy who were faced with ministering to scattered parishes, often numbering over 2,000 souls. In the 1798 Russian Census, Court Councilor Popov describes the colony of Warenburg and states that while the Lutheran families had their own pastor, the Reformed faith families did not belong to any parish. Still, when necessary, they called upon the pastor from Norka. The lack of pastors continued to be an acute problem. By 1805, there were only fifteen Protestant pastors in the entire colonial enclave, these living in Messer, Grimm, Beideck, Galka, Dietel, Frank, Norka, Stephan, Yagodnaya Polyana, Saratov, Rosenheim, Warenburg, Bettinger and two in Katharinenstadt. Protestant seminaries were eventually built to give students a better chance of studying closer to home. Despite this fact, shortages persisted and up to 1910, there were between three to five colonies in a Kirchenspiel (parish).

Adam Giesinger wrote, "It was difficult to attract Protestant pastors to the Volga in the early years, and even more difficult to hold them there." Giesinger goes on to say, "As life became more bearable in the Volga colonies the number of Protestant pastors who came to stay gradually increased." "It appears there were few outstanding men among the pastors who served in the Volga colonies during the first 50 years. Three of them, however, Janet, Cattaneo, and Huber, all Reformed, seem to have been above the ordinary." All of these men were trained in Switzerland.

The University of Dorpat (now the University of Tartu) in Estonia was the nearest theological school, but the great distance and expense virtually prevented enrollment by eligible Volga German men.

James Long provides a brief history of the early church leadership and efforts to reconcile the Lutheran and Reformed faiths: "In 1819 (July 20th), the government (of Czar Alexander I) attempted to erase, if not reconcile, differences between Lutherans and Calvinists (Reformed) by placing all Volga German Protestant parishes under the jurisdiction of the newly established Protestant Consistory in Saratov. Under the energetic leadership of a former priest and orientalist, Ignatius Fessler, the differences in the practices and liturgy of the two denominations narrowed as a common hymnal and liturgical manuals were adopted, and annual synods convened to discuss church affairs and to resolve problems. The Reformed Church had become so administratively integrated within the Lutheran parishes, and the two denominations' liturgical differences were so inconsequential that by decree in 1832, the consistory was renamed Lutheran and incorporated into the distant Moscow Lutheran Consistory (later called the National Church Council), which supervised congregations in various parts of the empire." The Moscow Consistory was responsible for inspecting the schools and churches and presiding over the annual synods of the pastors. With the passing of this decree, the Evangelical-Lutheran Church became a state church, just as the Orthodox church was. The Evangelical-Lutheran Church incorporated all Protestants in Russia, including Germans, Latvians, Estonians, and Finns. Until 1917, all the leaders of the church were Germans. The theological faculty in Dorpat (Estonia) was German, and the church's official language was German.

Specific tasks were undertaken by the "Benevolent Fund for Evangelical-Lutheran Churches in Russia," established in 1858. This organization made provisions for dependents of deceased pastors, financed the appointments of incumbents for poor churches, built churches and schools, provided theological training for colonist's sons, and established new parishes.

The Protestant congregations were divided into two deaneries in the districts of the Bergseite (hilly side of the river) and the Wiesenseite (plains side of the river). The deanery of the Bergseite consisted of 16 parishes, and the Wiesenseite comprised 23 parishes. Each deanery was served by a provost chosen by the pastors and confirmed by the Saratov Consistory for the religious affairs of foreign confessions and, later, the Moscow Lutheran Consistory.

Norka hosted the 31st Synod of Pastors of the Bergseite in 1865, the event's first occurrence outside the City of Saratov.

Norka hosted the 31st Synod of Pastors of the Bergseite in 1865, the event's first occurrence outside the City of Saratov.

Norka became a Pfarrkirche (parish church), which included the two Filialkirche (affiliated churches) of Huck (Splavnukha) and Neu-Messer. By 1906, Joseph Schnurr stated that the parish had a church membership of 23,179 souls served by one pastor. Another source provides the number of parish residents over various years: 12,832 (1886), 17,827 (1894), 20,700 (1905), and 24,040 (1911).

The pastor lived in Norka since it was the largest colony and parish center. A parsonage was built in Norka for the use of the pastor. From Norka, the pastor traveled to each congregation within the parish nearly every week, operating much like circuit riders in the United States. He had a semi-regular schedule of getting out to his villages to perform weddings, confirmations, baptisms, and funerals. He nearly always signed his name with the parish church center, but it did not mean he was physically present. In his absence, the Schulmeister (schoolmaster) performed these duties. This also explains the mass weddings held in these smaller parish villages. When the pastor came to town, a group of weddings were often performed on the same day.

The pastor lived in Norka since it was the largest colony and parish center. A parsonage was built in Norka for the use of the pastor. From Norka, the pastor traveled to each congregation within the parish nearly every week, operating much like circuit riders in the United States. He had a semi-regular schedule of getting out to his villages to perform weddings, confirmations, baptisms, and funerals. He nearly always signed his name with the parish church center, but it did not mean he was physically present. In his absence, the Schulmeister (schoolmaster) performed these duties. This also explains the mass weddings held in these smaller parish villages. When the pastor came to town, a group of weddings were often performed on the same day.

In addition to a state salary, the clergy was granted a payment of 180 rubles, secured by a special collection (Steuer) from the colonist's families. Large families paid 96 kopeks, medium families paid 80 kopeks, and small families paid 64 kopeks. In addition, a clergy received a free horse for travel and an additional payment for maintenance of his own horses at a rate set by special negotiation with a member of his parish as verified by the district commissar. The pastor also received payment of wheat, rye, barley, hay, potatoes, and wood. On average, the salary of a clergyman reached 500 to 600 rubles as opposed to a common laborer who earned about 12 rubles per year.

Jacob Dietz suggests that pastors were well compensated and occasionally had interests at odds with villagers. Colonists supplied most of the compensation a pastor received, other than the 180 rubles paid by the government annually (which gave them some protection against inflation, which paper money would not). For almost 100 years, an in-kind payment from each family was made (so many pud of wheat or rye, a faden of firewood, bales of hay, etc.) So, the more families per village, the more compensation for a pastor. The colonists, however, got tired of the crowding and difficulty of making a living as the population multiplied and wanted to move to open areas, which reduced the payments to the pastor. This seems to have been settled by a shift to compensation of pastors by a mainly fixed amount of money paid in salary by the congregations of a parish, other than religious rights, where the fee was set for baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and funerals, but the more of any of these, the more income. More land opened up around the same time, and villagers could move to these new areas.

According to Pastor Eduard Seib, the pastor and the schoolmaster were respected personalities. One asks them for advice and also usually receives good advice. Because of this, the saying “The pastor said so” usually dismissed any statement to the contrary. One shows respect toward him by one’s behavior. If he strolls through the village when the gate benches are still occupied, all stand up when the pastor passes by, and even the oldest people remove their head covering and address a greeting to him in a friendly and respectful manner. The same is true of the relationship between the schoolchildren and the schoolmaster. However, such deference is also shown toward the priest at home (Translator’s note: This is in reference to the Christian teaching emphasized by Dr. Martin Luther that the father of the house is also the pastor of the home). When one walks past an elderly man, one moves to the side and, in doing so, says good-day first. It is considered immodest to smoke in front of an elderly man, the schoolmaster, or the pastor. Any members of the congregation with an especially close relationship with the pastor or the schoolmaster often make them glad by giving them some practical gift. Both receive shortcakes from these members at weddings and on major holidays. Each of them also gets a sausage or another meat product from the feast held after butchering is completed (the Metzelsuppe).

However, even though they are held in great esteem and respected, now and again, there are differences of opinion between a pastor and his congregation. This seems to be more prevalent in two situations. Differences of opinion are almost unavoidable when the construction of a new church is planned or when a new schoolmaster is to be hired. The wishes and opinions of both parties are often at loggerheads with each other, and a lot of effort and patience is required until everything has come to its proper conclusion. If the pastor appreciates his people and they see that he means them well, then the pastor is assured of winning. The people usually put up a little resistance because it “does bother them a bit,” but in the end, they agree with him and are satisfied.

A native Volga German, Pastor Wilhelm Stärkel (Translator’s note: His name was spelled Störkel until 1859. He was born in 1839), a graduate of the Mission Seminary in Basel (Switzerland), once dealt with the members of his parish in a curious way. He employed the colonists’ belief in dreams. They do not always consider dreams to be illusions. After one of his congregations had been entangled in a dispute about which schoolmaster was to be selected, and as yet no end to the dispute was in sight, he began a sermon which he held there with these words: “I had a dream last night! (Everyone paid close attention!) I was in hell and wanted to visit Satan one time. It was pitch-dark around me. Only from a great distance did I perceive a bright light. I thought that he was probably raking his fire there. I walked toward this light, which became brighter and brighter all the time, but I could not detect that Satan was anywhere. When I was finally right next to the fire, I discovered a little devil that was doing something to his foot. I turned to him and asked him where Satan and his angels could be. I would really like to see them. “Yes,” said the imp in a whining tone of voice, “They are all in Hell; there is a vote being held there to elect a schoolmaster for the congregation.” (All the people in the worship service lowered their heads.) “I would have really liked to go along (with Satan and his angels), but I have a bad foot, and because of that, I had to stay at home.” That very afternoon, a schoolmaster was elected to the satisfaction of the pastor and later to the satisfaction of the congregation.

Despite respect and reverence on the part of the people, a pastor could also become the victim of satire. This is exemplified by a poem about Pastor Jakob Friedrich Dettling, which, in fact, should have been written with the aid of an educated man (a certain Professor Ascher allegedly from Heidelberg). Pastor Dettling was the pastor in Messer, where he served from 1855 to 1891. An unpretentious, honest Swabian, also educated at the Basel Mission Seminary, a man with a rugged exterior and a mighty preacher of repentance gifted with the voice of a lion. He is supposed to have seen and read this poem while he was still living.

Jacob Dietz suggests that pastors were well compensated and occasionally had interests at odds with villagers. Colonists supplied most of the compensation a pastor received, other than the 180 rubles paid by the government annually (which gave them some protection against inflation, which paper money would not). For almost 100 years, an in-kind payment from each family was made (so many pud of wheat or rye, a faden of firewood, bales of hay, etc.) So, the more families per village, the more compensation for a pastor. The colonists, however, got tired of the crowding and difficulty of making a living as the population multiplied and wanted to move to open areas, which reduced the payments to the pastor. This seems to have been settled by a shift to compensation of pastors by a mainly fixed amount of money paid in salary by the congregations of a parish, other than religious rights, where the fee was set for baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and funerals, but the more of any of these, the more income. More land opened up around the same time, and villagers could move to these new areas.

According to Pastor Eduard Seib, the pastor and the schoolmaster were respected personalities. One asks them for advice and also usually receives good advice. Because of this, the saying “The pastor said so” usually dismissed any statement to the contrary. One shows respect toward him by one’s behavior. If he strolls through the village when the gate benches are still occupied, all stand up when the pastor passes by, and even the oldest people remove their head covering and address a greeting to him in a friendly and respectful manner. The same is true of the relationship between the schoolchildren and the schoolmaster. However, such deference is also shown toward the priest at home (Translator’s note: This is in reference to the Christian teaching emphasized by Dr. Martin Luther that the father of the house is also the pastor of the home). When one walks past an elderly man, one moves to the side and, in doing so, says good-day first. It is considered immodest to smoke in front of an elderly man, the schoolmaster, or the pastor. Any members of the congregation with an especially close relationship with the pastor or the schoolmaster often make them glad by giving them some practical gift. Both receive shortcakes from these members at weddings and on major holidays. Each of them also gets a sausage or another meat product from the feast held after butchering is completed (the Metzelsuppe).

However, even though they are held in great esteem and respected, now and again, there are differences of opinion between a pastor and his congregation. This seems to be more prevalent in two situations. Differences of opinion are almost unavoidable when the construction of a new church is planned or when a new schoolmaster is to be hired. The wishes and opinions of both parties are often at loggerheads with each other, and a lot of effort and patience is required until everything has come to its proper conclusion. If the pastor appreciates his people and they see that he means them well, then the pastor is assured of winning. The people usually put up a little resistance because it “does bother them a bit,” but in the end, they agree with him and are satisfied.

A native Volga German, Pastor Wilhelm Stärkel (Translator’s note: His name was spelled Störkel until 1859. He was born in 1839), a graduate of the Mission Seminary in Basel (Switzerland), once dealt with the members of his parish in a curious way. He employed the colonists’ belief in dreams. They do not always consider dreams to be illusions. After one of his congregations had been entangled in a dispute about which schoolmaster was to be selected, and as yet no end to the dispute was in sight, he began a sermon which he held there with these words: “I had a dream last night! (Everyone paid close attention!) I was in hell and wanted to visit Satan one time. It was pitch-dark around me. Only from a great distance did I perceive a bright light. I thought that he was probably raking his fire there. I walked toward this light, which became brighter and brighter all the time, but I could not detect that Satan was anywhere. When I was finally right next to the fire, I discovered a little devil that was doing something to his foot. I turned to him and asked him where Satan and his angels could be. I would really like to see them. “Yes,” said the imp in a whining tone of voice, “They are all in Hell; there is a vote being held there to elect a schoolmaster for the congregation.” (All the people in the worship service lowered their heads.) “I would have really liked to go along (with Satan and his angels), but I have a bad foot, and because of that, I had to stay at home.” That very afternoon, a schoolmaster was elected to the satisfaction of the pastor and later to the satisfaction of the congregation.

Despite respect and reverence on the part of the people, a pastor could also become the victim of satire. This is exemplified by a poem about Pastor Jakob Friedrich Dettling, which, in fact, should have been written with the aid of an educated man (a certain Professor Ascher allegedly from Heidelberg). Pastor Dettling was the pastor in Messer, where he served from 1855 to 1891. An unpretentious, honest Swabian, also educated at the Basel Mission Seminary, a man with a rugged exterior and a mighty preacher of repentance gifted with the voice of a lion. He is supposed to have seen and read this poem while he was still living.

Wenn alle Leut noch schlafen, |

When the people are all still asleep, |

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the church lost much of its authority. A decree on the "Separation of Church and State," along with other laws, paralyzed the churches whose governing bodies were primarily composed of government officials. More than 1,000 church schools were closed, and they no longer owned their buildings. The Bolsheviks confiscated all valuable religious objects by force. Religious instruction was banned or severely restricted.

In 1923, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Russia became a member of the Lutheran World Congress. A seminary opened in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in 1925, replacing the lost connection to Dorpat, now part of autonomous Estonia. The "Theological College" existed until 1934, but after 1930, regular instruction was no longer possible. Tutors were arrested, as were candidates and graduates. Of the 57 pastors trained, only a few could provide ministry for any length of time. Many were sent to labor camps, including Norka's last pastor, Emil Pfeiffer, and some escaped from Russia.

Between 1917 and 1937, 130 of the 350 Protestant pastors were arrested and suffered from repression, 15 pastors were executed by shooting, 22 died in prisons, and more than 100 emigrated from Russia. Between 1936 and 1938, Stalin's terror destroyed all manifestations of church and religious life. All expressions of spiritual life were concealed due to fear of arrest and potential execution.

Following the arrest of Rev. Pfeiffer in 1934, the Commission for Cultural Matters informed the Presidium of the Volga German Autonomous Republic on August 28th that the church in Norka had been closed. However, the faithful were still holding services there. The congregation was told they had one week to repay any outstanding church debts and building taxes for the previous five years if they wanted the building. The tax rate was calculated as 8 percent of the construction cost for the building. The congregation was in an impossible position and could not pay this enormous amount. As a result, the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee decided to shutter the church permanently on October 3, 1934. The church building was to be used as a Soviet cultural center going forward. Johann Georg Schleuning recalls that the building was used as the state grain warehouse until it was completely destroyed in the late 1930s.

The deportation of ethnic Germans in 1941 did not have a material impact on religious life since most aspects had been destroyed in the 1930s. Religious faith survived secretly in families or small groups of friends. Over time, funerals, which were rarely disturbed or monitored by Soviet officials, became opportunities to openly display religious beliefs.

By the mid-1950s, religion was more tolerated by Soviet officials. By 1975, it was possible to register German churches in Russia. By 1983, 129 German Lutheran churches had been established. Part of this government relaxation was aimed at stemming emigration. Despite these small steps at restoring religious practices, it was common for the KGB (Soviet secret police) to infiltrate and influence the congregations.

In 1923, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Russia became a member of the Lutheran World Congress. A seminary opened in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in 1925, replacing the lost connection to Dorpat, now part of autonomous Estonia. The "Theological College" existed until 1934, but after 1930, regular instruction was no longer possible. Tutors were arrested, as were candidates and graduates. Of the 57 pastors trained, only a few could provide ministry for any length of time. Many were sent to labor camps, including Norka's last pastor, Emil Pfeiffer, and some escaped from Russia.

Between 1917 and 1937, 130 of the 350 Protestant pastors were arrested and suffered from repression, 15 pastors were executed by shooting, 22 died in prisons, and more than 100 emigrated from Russia. Between 1936 and 1938, Stalin's terror destroyed all manifestations of church and religious life. All expressions of spiritual life were concealed due to fear of arrest and potential execution.

Following the arrest of Rev. Pfeiffer in 1934, the Commission for Cultural Matters informed the Presidium of the Volga German Autonomous Republic on August 28th that the church in Norka had been closed. However, the faithful were still holding services there. The congregation was told they had one week to repay any outstanding church debts and building taxes for the previous five years if they wanted the building. The tax rate was calculated as 8 percent of the construction cost for the building. The congregation was in an impossible position and could not pay this enormous amount. As a result, the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee decided to shutter the church permanently on October 3, 1934. The church building was to be used as a Soviet cultural center going forward. Johann Georg Schleuning recalls that the building was used as the state grain warehouse until it was completely destroyed in the late 1930s.

The deportation of ethnic Germans in 1941 did not have a material impact on religious life since most aspects had been destroyed in the 1930s. Religious faith survived secretly in families or small groups of friends. Over time, funerals, which were rarely disturbed or monitored by Soviet officials, became opportunities to openly display religious beliefs.

By the mid-1950s, religion was more tolerated by Soviet officials. By 1975, it was possible to register German churches in Russia. By 1983, 129 German Lutheran churches had been established. Part of this government relaxation was aimed at stemming emigration. Despite these small steps at restoring religious practices, it was common for the KGB (Soviet secret police) to infiltrate and influence the congregations.

Sources

Dietz, Jacob E. History of the Volga German Colonists. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Printed by Augstums Printing Service, 2005. 114. Print.

Giesinger, Adam. From Catherine to Khrushchev: The Story of Russia's Germans. Winnipeg, Man.: A. Giesinger, 1974. Print.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. Print.

Pleve, Igor. Einwanderung in Das Wolgagebiet 1764-1767 Kolonien Laub- Preuss. Gottingen: Nordost-Institut, 2005. Print.

Schnurr, Joseph. Die Kirchen Und Das Religiöse Leben Der Rußlanddeutschen. Stuttgart: AER-Verl., 1978. Print.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums."Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): Print.

Stricker, Gerd. "German Protestants in Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia. Lincoln, Nebraska. Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring 1988), page 49. Translated by Gill Ablitt.

Der Wolgabote Kalendar 1891. Saratov, Russia, Verlag von W. Himmel, 1890.

Giesinger, Adam. From Catherine to Khrushchev: The Story of Russia's Germans. Winnipeg, Man.: A. Giesinger, 1974. Print.

Long, James. From Privileged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 1988. Print.

Pleve, Igor. Einwanderung in Das Wolgagebiet 1764-1767 Kolonien Laub- Preuss. Gottingen: Nordost-Institut, 2005. Print.

Schnurr, Joseph. Die Kirchen Und Das Religiöse Leben Der Rußlanddeutschen. Stuttgart: AER-Verl., 1978. Print.

Seib, Eduard. "Der Wolgadeutsche im Spiegel seines Brauchtums."Heimatbuch Der Deutschen Aus Russland 1967/1968 (1968): Print.

Stricker, Gerd. "German Protestants in Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union." Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia. Lincoln, Nebraska. Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring 1988), page 49. Translated by Gill Ablitt.

Der Wolgabote Kalendar 1891. Saratov, Russia, Verlag von W. Himmel, 1890.

Last updated November 21, 2023