History > Planning for the Colonists

Planning for the Colonists 1764 - 1766

This article was written for Steven Schreiber in 2002 by Vera Beljakova-Miller and is based on her research and the book Deutsche Architektur an der Wolga (German Architecture on the Volga) by Dr. Sergei Terjochin. Dr. Terjochin graduated from the Saratov Polytechnical Institute and the Institute of Architecture and Town-Planning in Moscow. Dr. Terjochin is the great-grandson of Volga German colonist Andreas Stoll, who operated a steam mill with his brothers since 1897 in Pokrovsk, Russia (now Engels).

The Russian government did a great deal of planning for the settlement of the Volga colonies in hopes of creating an orderly development.

One often hears that the Volga Germans arrived to find no housing on the Volga, quoting Adam Giesinger from his book titled from Catherine to Khrushchev, "in most cases, there was no housing as promised by the agent," who in turn refers to the work by Gottlieb Beratz (The German Colonies on the Lower Volga).

The operative word here is "as promised by the agents" – who, after all, were "salesmen" trying to recruit as many new settlers as possible for their own financial gain. The recruitment agents had contracts and quotas to fulfill and were meant to deliver a certain agreed-upon number of new settlers. They were thus prone to over-sell and exaggeration.

In fact, Catherine the Great's Manifesto of 1763 did not promise ready-built housing. No country, especially in the 18th century, built housing for new settlers - not even enlightened Great Britain, which dumped its 1822 settlers in South Africa on a raw coastline amidst warring native tribes. It was very unusual at this time for a state to provide housing for new settlers. Giving them free land was considered generous enough. Giving them building materials or money was deemed most kind. Nonetheless, there is evidence that housing and materials were provided to the colonists over time.

One often hears that the Volga Germans arrived to find no housing on the Volga, quoting Adam Giesinger from his book titled from Catherine to Khrushchev, "in most cases, there was no housing as promised by the agent," who in turn refers to the work by Gottlieb Beratz (The German Colonies on the Lower Volga).

The operative word here is "as promised by the agents" – who, after all, were "salesmen" trying to recruit as many new settlers as possible for their own financial gain. The recruitment agents had contracts and quotas to fulfill and were meant to deliver a certain agreed-upon number of new settlers. They were thus prone to over-sell and exaggeration.

In fact, Catherine the Great's Manifesto of 1763 did not promise ready-built housing. No country, especially in the 18th century, built housing for new settlers - not even enlightened Great Britain, which dumped its 1822 settlers in South Africa on a raw coastline amidst warring native tribes. It was very unusual at this time for a state to provide housing for new settlers. Giving them free land was considered generous enough. Giving them building materials or money was deemed most kind. Nonetheless, there is evidence that housing and materials were provided to the colonists over time.

Map showing the area around the frontier town of Saratov in 1745, prior to the settlement of the Volga Germans beginning in 1764. No settlements are shown in the area where Norka was established in August 1767. Source: "Delineatio Fluvii Volgae a Samara usque ad Tsaricin" from the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

A new chancellery was founded in St. Petersburg for the guardianship of all foreign settlers (not only the Volga Germans) after the first two manifestoes in 1762 and 1763.

The first settlers arrived in 1764 and continued coming to the Volga (Saratov) region until 1773, but now in reduced numbers. In total, 5,549 families arrived, comprised of 30,930 persons, with each family entitled to 30 free desyatinas (about 1 hectare or 3 acres).

Count Grigory Orlov, who oversaw this influx of settlers, decided in 1764 that one needs proper land surveying and town planning for the future growth of the new villages. (Note: Orlov made a report on conditions in Norka in 1769)

The first settlers arrived in 1764 and continued coming to the Volga (Saratov) region until 1773, but now in reduced numbers. In total, 5,549 families arrived, comprised of 30,930 persons, with each family entitled to 30 free desyatinas (about 1 hectare or 3 acres).

Count Grigory Orlov, who oversaw this influx of settlers, decided in 1764 that one needs proper land surveying and town planning for the future growth of the new villages. (Note: Orlov made a report on conditions in Norka in 1769)

To this purpose, Orlov congregated a team of experts from the Cadet-Engineers and Artillery Corps of the army. In those days, the army performed the state’s civil engineering projects - all were expert land surveyors and geodetic surveyors.

Count Orlov collected a team of 24 under the leadership of Colonel Ivan (Johann) Reis, a man of noble rank and a collegial assessor with a salary of 600 rubles per year. Reis was sent to Saratov in the spring of 1764 to prepare to receive the colonists, inspect the steppe, and find places to settle the foreigners. Reis also dispatched detachments of surveyors to survey the area of settlement.

The team headed by Reis included various other ethnic Germans of an earlier professional vintage:

Land-surveyor supervisors: Ph. Wiegel, I. Von Lipgard, plus two Russians.

Land surveyors: W. Rehbinder and six Russians.

Geodetic surveyors: O. Binse-Weden and four Russians, but the other seven surveyors are lost to history.

These men were professional (military) engineers and officers, many of whom spoke German, and they were now instructed to design new villages. For example, Von Liphard and von Rehbinder belonged to the famous old Baltic German nobility.

Their task was to find suitable locations, survey them, and offer advice. The land surveyors had to draw up the land. Together, the team had to propose layouts for villages: housing, church, school, meeting hall, plow land, meadows, pastures, hay meadows, woodland (where applicable), as well as ditches and moats for protection, not forgetting sheds, farm yards, stabling, etc.

All along, the traveling schedules and routes of the settlers were planned so that the new settlers would not arrive on the Volga before the April-May time frame, which is the beginning of the mid-Volga construction season. Wintering quarters had been constructed on the Volga but were not reached before the river froze; the settlers over-wintered in Russian villages instead.

On arrival in Saratov, settlers were housed in the army barracks - 16 long ones outside the city, where their particulars were noted down, and they were sorted into groups to make up future village populations, according to friends and families and religious groupings.

The group leaders (Vorsteher), who were mainly the same people the travelers had chosen on their ships, were shown the available sites on maps and the plans for selecting their village location, mainly on the Volga or other small rivers or in dales.

We do not know how well these group leaders understood map reading. However, first come, first served, and the earlier settlers certainly had the widest choice of land and location.

After the site selection and calculation of the number of future residents, the elders were presented with some 12 blueprints of village layouts that would suit their given numbers. Again, the elders were asked to select. These plans are still available and are used by the author.

Then, the land, including fields, houses, and buildings, was pegged out by Russian engineers so that the settlers could not argue among themselves, fight over parcels of land, or cheat one another.

Building material was provided "if and when available" - all biographies of this region are united in describing the lack of lumber. Lumber was floated down the Volga River from up north, but there was never enough. Hence, most of the local abodes were constructed of mud and wattle.

Some villages were better provided for than others. Settlers recruited by the Russian "Crown" (such as Norka) got a better deal than "Agent-director" settlers. In many cases, the Crown had met its obligation and provided housing, unlike the agents who seemed more disorganized or plain disinterested, lacked concern, or maybe were just very inexperienced, for indeed, how does one expect French barons to understand village construction for Germans in Russia’s frontier land.

Next, a most important point. The Russian State knew and understood that the settlers would only be able to build "temporary" accommodation from plan initially, before the onset of autumn, with August-September being the end of the building season and the beginning of the rainy period. All slush and mud everywhere.

The Russian State knew and understood that it would take the settlers up to 3 years to settle and construct "proper" accommodation and buildings.

In the interim, the Russian State sent serfs from state land and state villages to teach the colonists how to build temporary accommodation, which was then widely used: wattle-and-mud huts. The state serfs included builders, carpenters, smiths, and wagon makers. Their job was to help the colonists and show them how to adapt to Russian climatic conditions.

Johann Reis was responsible for surveying, laying out, and pegging out 106 settler colonies in just two 2 years, up to 1767 - no mean feat!

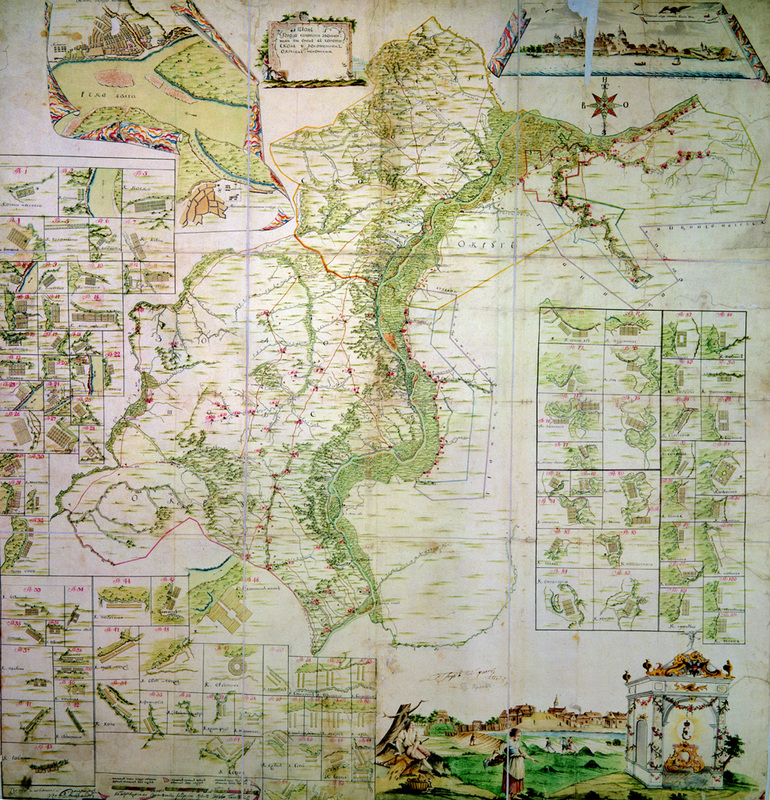

On completion of the project, Reis and his team returned to St. Petersburg to produce a huge map showing all the locations of the new colonies decorated with smaller individual sketches and maps of the layouts for every village, even showing all the individual homes and farm yards.

Count Orlov collected a team of 24 under the leadership of Colonel Ivan (Johann) Reis, a man of noble rank and a collegial assessor with a salary of 600 rubles per year. Reis was sent to Saratov in the spring of 1764 to prepare to receive the colonists, inspect the steppe, and find places to settle the foreigners. Reis also dispatched detachments of surveyors to survey the area of settlement.

The team headed by Reis included various other ethnic Germans of an earlier professional vintage:

Land-surveyor supervisors: Ph. Wiegel, I. Von Lipgard, plus two Russians.

Land surveyors: W. Rehbinder and six Russians.

Geodetic surveyors: O. Binse-Weden and four Russians, but the other seven surveyors are lost to history.

These men were professional (military) engineers and officers, many of whom spoke German, and they were now instructed to design new villages. For example, Von Liphard and von Rehbinder belonged to the famous old Baltic German nobility.

Their task was to find suitable locations, survey them, and offer advice. The land surveyors had to draw up the land. Together, the team had to propose layouts for villages: housing, church, school, meeting hall, plow land, meadows, pastures, hay meadows, woodland (where applicable), as well as ditches and moats for protection, not forgetting sheds, farm yards, stabling, etc.

All along, the traveling schedules and routes of the settlers were planned so that the new settlers would not arrive on the Volga before the April-May time frame, which is the beginning of the mid-Volga construction season. Wintering quarters had been constructed on the Volga but were not reached before the river froze; the settlers over-wintered in Russian villages instead.

On arrival in Saratov, settlers were housed in the army barracks - 16 long ones outside the city, where their particulars were noted down, and they were sorted into groups to make up future village populations, according to friends and families and religious groupings.

The group leaders (Vorsteher), who were mainly the same people the travelers had chosen on their ships, were shown the available sites on maps and the plans for selecting their village location, mainly on the Volga or other small rivers or in dales.

We do not know how well these group leaders understood map reading. However, first come, first served, and the earlier settlers certainly had the widest choice of land and location.

After the site selection and calculation of the number of future residents, the elders were presented with some 12 blueprints of village layouts that would suit their given numbers. Again, the elders were asked to select. These plans are still available and are used by the author.

Then, the land, including fields, houses, and buildings, was pegged out by Russian engineers so that the settlers could not argue among themselves, fight over parcels of land, or cheat one another.

Building material was provided "if and when available" - all biographies of this region are united in describing the lack of lumber. Lumber was floated down the Volga River from up north, but there was never enough. Hence, most of the local abodes were constructed of mud and wattle.

Some villages were better provided for than others. Settlers recruited by the Russian "Crown" (such as Norka) got a better deal than "Agent-director" settlers. In many cases, the Crown had met its obligation and provided housing, unlike the agents who seemed more disorganized or plain disinterested, lacked concern, or maybe were just very inexperienced, for indeed, how does one expect French barons to understand village construction for Germans in Russia’s frontier land.

Next, a most important point. The Russian State knew and understood that the settlers would only be able to build "temporary" accommodation from plan initially, before the onset of autumn, with August-September being the end of the building season and the beginning of the rainy period. All slush and mud everywhere.

The Russian State knew and understood that it would take the settlers up to 3 years to settle and construct "proper" accommodation and buildings.

In the interim, the Russian State sent serfs from state land and state villages to teach the colonists how to build temporary accommodation, which was then widely used: wattle-and-mud huts. The state serfs included builders, carpenters, smiths, and wagon makers. Their job was to help the colonists and show them how to adapt to Russian climatic conditions.

Johann Reis was responsible for surveying, laying out, and pegging out 106 settler colonies in just two 2 years, up to 1767 - no mean feat!

On completion of the project, Reis and his team returned to St. Petersburg to produce a huge map showing all the locations of the new colonies decorated with smaller individual sketches and maps of the layouts for every village, even showing all the individual homes and farm yards.

The branch office of the Guardianship Chancellery of the Foreign Settlers had a staff of 27 in Saratov, including the chief judge, the secretary, the archivist, and translators...it even had a small company of soldiers to protect the settlers, which – however - proved inadequate when a few years later the Pugachev Rebellion (“Peasant Wars”) ran amok until Catherine II sent in her most able generals….several of whom also carried German surnames, like the renowned Michelsohnen.

What is very interesting: The colonists’ town-planning department became a national institution and functioned for 30 years, surveying, planning, pegging out 400 new Russian towns. Such a formal national town planning institution was also considered a world first!

Russia often settled new villages with foreigners, prisoners-of-war (Swedes), Russian state serfs, and retired soldiers, while private landowners settled new villages on newly bought land with their own serfs from other estates. None, of course, have “pre-built” housing! That was the task of the newcomers.

Conclusion:

It is clear that Russia intended the settlers to arrive at the beginning of the building season and erect their own initial temporary homes, similar to those inhabited by the Russian peasantry, who lacked lumber. The wattle-and-mud huts were envisaged to last some 3 years, during which period the settlers would erect more permanent structures. Some colonists, though, did find pre-built housing, which was put up by the local Russian peasants in anticipation of the settlers’ arrival.

But German Russian history books talk of the settlers feeling let down because there was no housing waiting for them; therefore, I conclude that the agents had over-promised services and infrastructure to the German settlers to increase recruitment numbers.

What is very interesting: The colonists’ town-planning department became a national institution and functioned for 30 years, surveying, planning, pegging out 400 new Russian towns. Such a formal national town planning institution was also considered a world first!

Russia often settled new villages with foreigners, prisoners-of-war (Swedes), Russian state serfs, and retired soldiers, while private landowners settled new villages on newly bought land with their own serfs from other estates. None, of course, have “pre-built” housing! That was the task of the newcomers.

Conclusion:

It is clear that Russia intended the settlers to arrive at the beginning of the building season and erect their own initial temporary homes, similar to those inhabited by the Russian peasantry, who lacked lumber. The wattle-and-mud huts were envisaged to last some 3 years, during which period the settlers would erect more permanent structures. Some colonists, though, did find pre-built housing, which was put up by the local Russian peasants in anticipation of the settlers’ arrival.

But German Russian history books talk of the settlers feeling let down because there was no housing waiting for them; therefore, I conclude that the agents had over-promised services and infrastructure to the German settlers to increase recruitment numbers.

Last updated November 19, 2023