Memories of Norka

by Conrad Brill

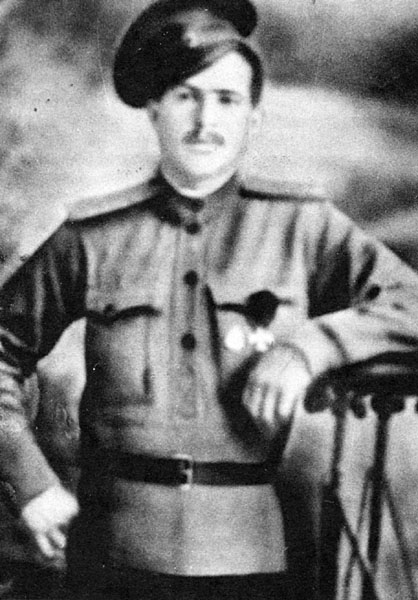

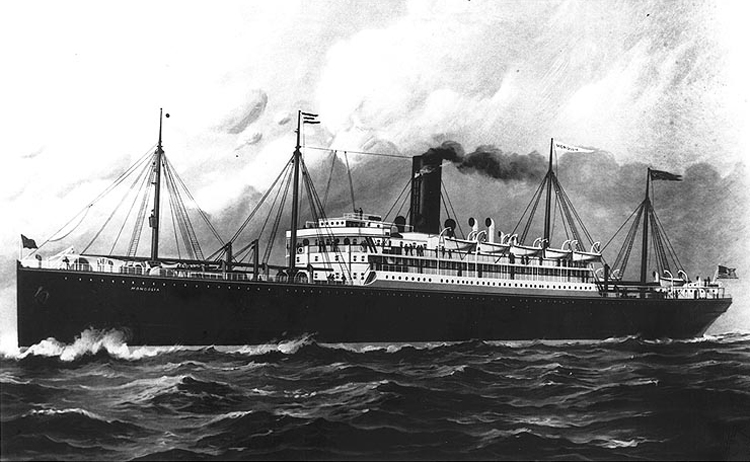

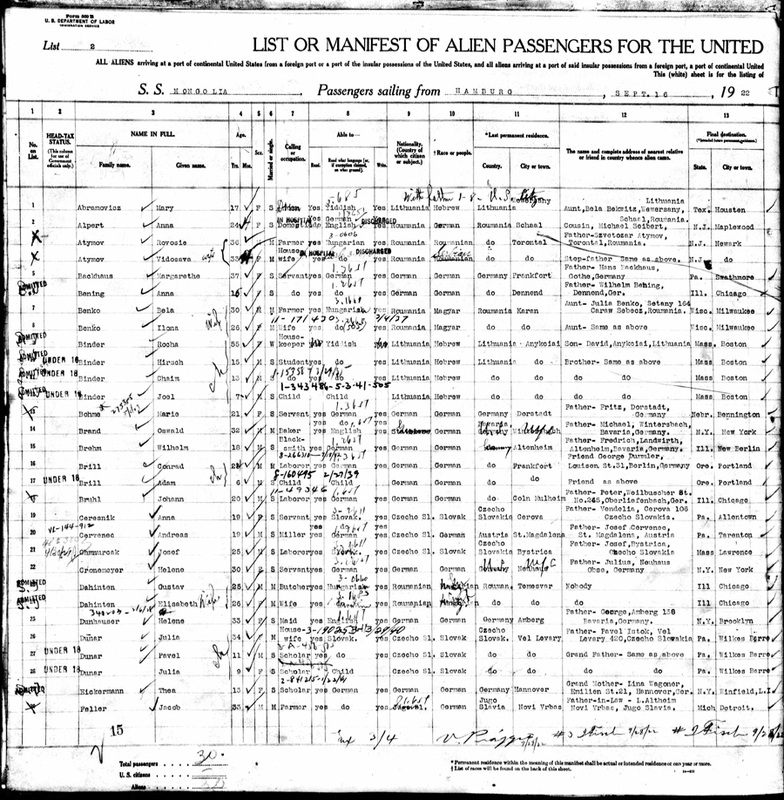

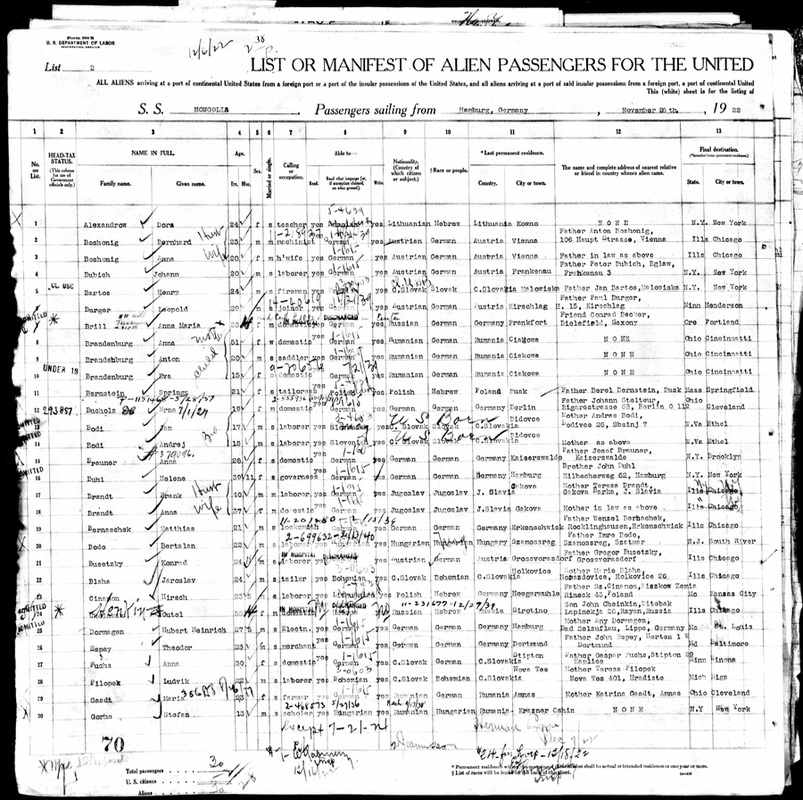

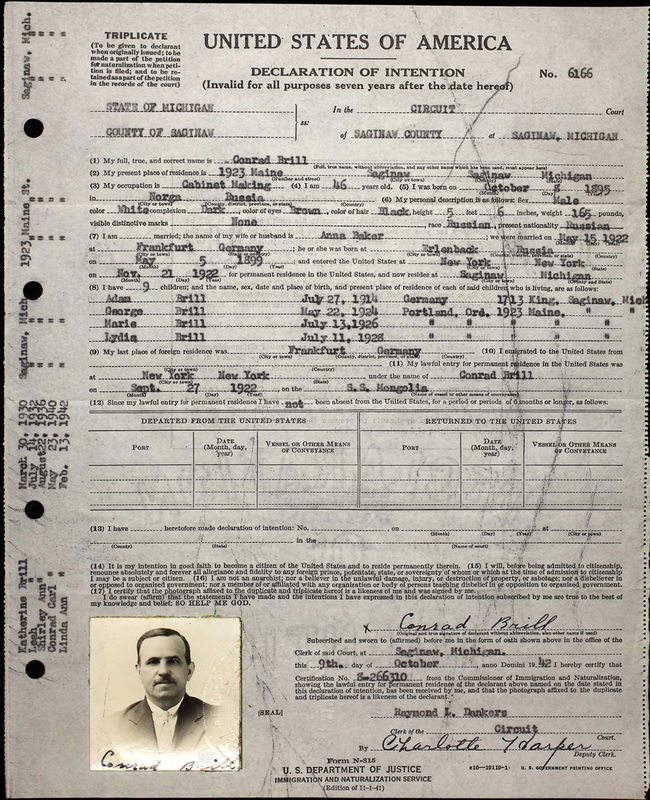

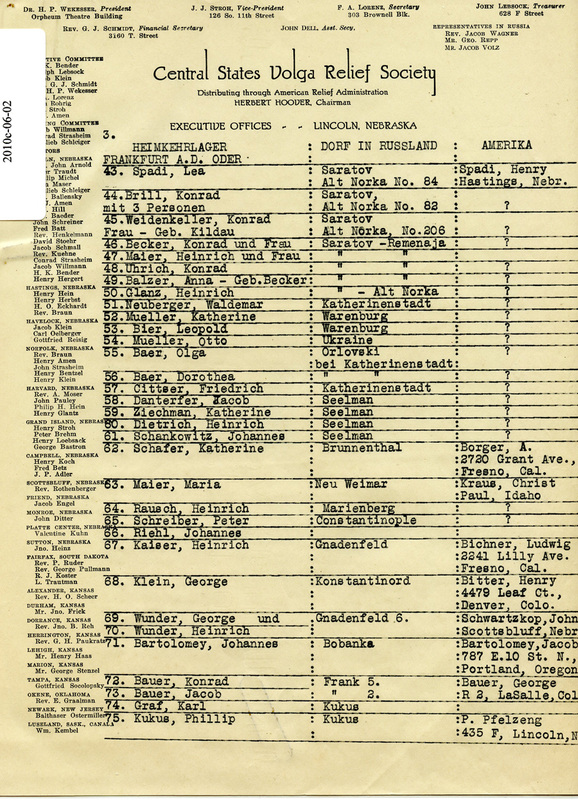

These are the memoirs of Konretja (Conrad) Brill, who was born in Norka, Russia on October 8, 1895. After having served with the Russian Army during World War I, Conrad left Norka on Christmas Eve 1921 with his first wife and seven-year-old son, Adam. His wife died of influenza on the journey, but Conrad and his son were able to reach a refugee camp at Frankfurt an der Oder, Germany. There he met Anna Becker, who was from the colony of Erlenbach and wanted to come to the United States to join her brother and sister. Conrad and Anna were married in Frankfurt an der Oder in 1922 and arrived in New York later that year. This story tells of Conrad's childhood in Norka, some of his experiences in the Imperial Russian Army, his flight from Russia and journey to the United States, where he resided in Portland, Oregon. These memoirs were told to his son, George Brill, who spent many hours listening to the experiences and memories of his father. George recorded Conrad's memory on paper as a tribute to his father. George also drew a plat of Norka, which shows where relatives and friends of Conrad lived. The stories told by Conrad in the original manuscript are not intended to be taken as derogatory gossip, but are meant to be helpful to others interested in family history and genealogy.

Conrad's memories provide a unique and rich understanding of life in Norka. You may even find that that he mentions one of your ancestors or relatives.

Conrad's memories provide a unique and rich understanding of life in Norka. You may even find that that he mentions one of your ancestors or relatives.

My Memories of Russian Life

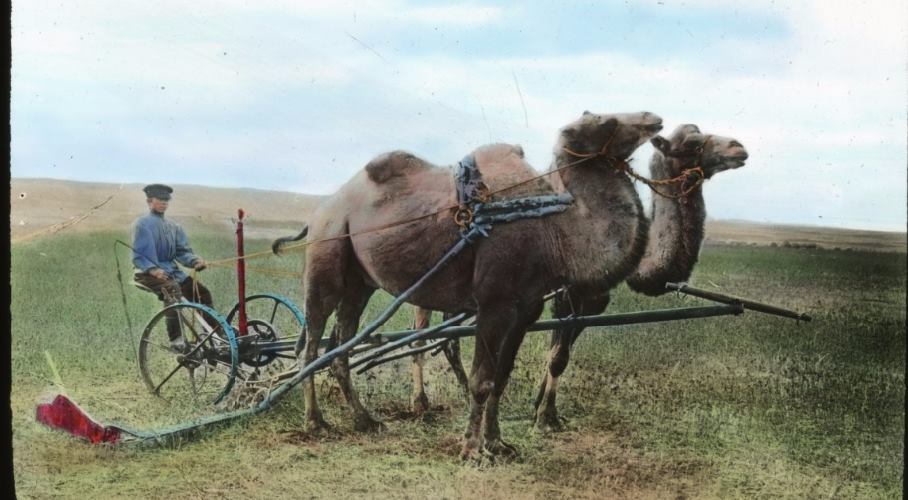

The country of Russia is geographically isolated on three sides by seas, deserts and mountains, so only the people living on the western border came into contact with civilized cultures in the earlier times. Most of these people getting education, were educated in Poland, Germany, France and England. The people living in the interior of Russia were nomadic tribes of Kirghiz, Kalmucks, Mongolians and Cossacks whose lifestyles were as the American Indians in the United States of America, before the white man came. When Catherine the Great (Catherine II) gave our German ancestors the chance for land to start Volga German villages, these nomadic tribes were reduced to serfdom to the wealthier Russians, so you can better understand how they came to hate our people.

The size of Russia is breath taking. It encompasses one-sixth of the earth’s land surface. It is three times the size of the United States and larger than all of North America. It stretches nearly halfway around the globe. There are ten time zones in Russia, so must set your watch ten times if you travel between the Gulf of Finland and the Bering Straits. Russia was under the rule of a Czar, but living in a free enterprise system, so the rich people were able to have summer homes on the steppes and winter homes in the large cities. The poor lived like the slaves of the southern United States and the land in the interior of Russia lay as a wasteland occupied only sparsely by these wild tribes who made raids on outlying villages, to steal horses and cattle, even kidnapping herders.

In 1763, Catherine the Great offered free land to people from other parts of the world, as was the land in the United States open for migration from other countries of Europe. Our ancestors who were German and having just gone through the Seven Years' War were lured there in hopes of starting over on the fertile land along the Volga River. Twenty-seven thousand (27,000) people made the move and 957 of them founded Norka, Russia on August 15, 1767, where my grandfather, Heinrich Brill was born, then my father George, in 1848 and finally me, on October 8, of 1895. I don't know which of the two original immigrants is our ancestor.

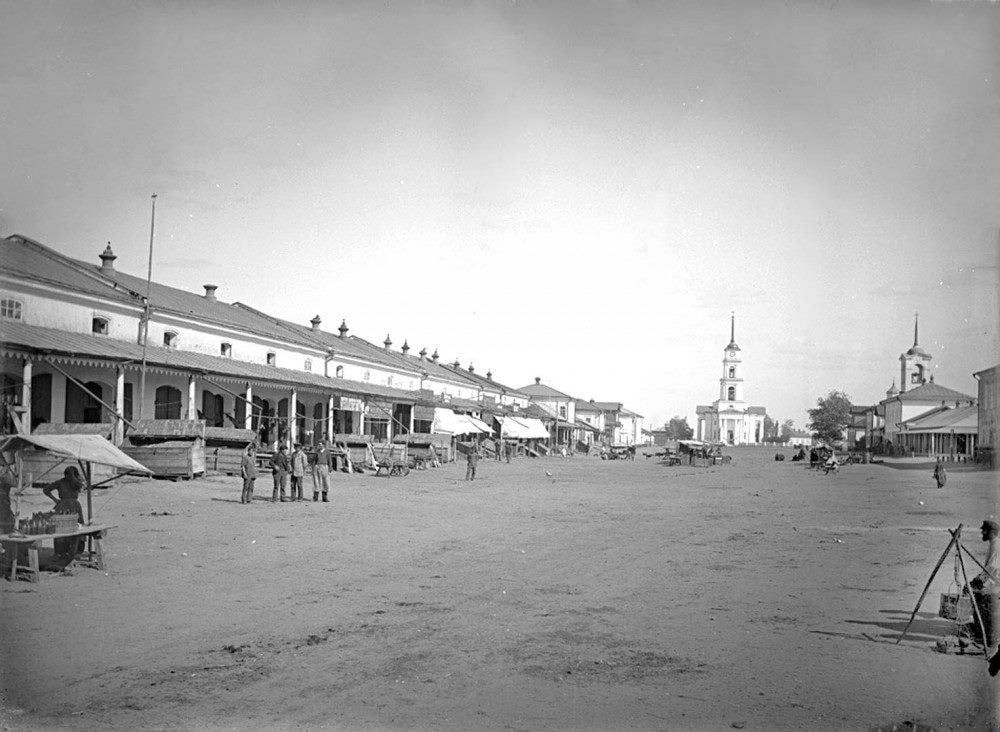

The village of Norka lay west of the city of Schilling, which was on the Volga River. Schilling was a port city, where the farmers of Norka hauled their grain, which was sold to buyers from different parts of Russia, Germany, and other European countries. You could buy 100 watermelons for a ruble from barges in Schilling when I was growing up. A ruble is like a dollar. You could buy lumber in Schilling, as the logs were floated from logging areas to Schilling in log rafts, then sawed into lumber and wood products. Russian fishermen there caught fish the Germans bought, or traded them grain, eggs or other products. The Russians would rather trade, than do business for cash. Schilling was similar to Portland, Oregon, both having rivers through center of city, and probably the reason my relatives chose to live here after trying several other states in the United States.

The poor people in the cities of Russia started their rebelling as early as I can remember, being born in the 1890's, but because of the size of the country there wasn't really any way to organize solidly. The secret police of the Czar’s era were probably as plentiful if not more so, than what we know of the Russian KGB and our FBI or CIA today. It wasn't until Lenin was embittered and outraged by the execution of his brother, Alexander, that he decided to spend the rest of his life fighting for the betterment of the working class and avenging his brothers’ death. He hadn't lived in poverty himself as a young person, but would spend almost the rest of his life hiding in Russian towns, foreign countries or exiled to Siberia in his battle against the Czarist regime.

The rage against the Czar and the rich soon engulfed more innocent people, who had no political power or desire to change anything. In 1905, while the Russian army was fighting Japan, people in the cities started a revolt, known as Bloody Sunday. They invaded stores owned by Jews, throwing the merchandise out of the windows and their family members or other people carted the loot home, similar to the Watts riots in California. Our German ancestors had been promised freedom of religion, military service and the right to maintain their own schools in the German language. This was all soon eroded and they were drafted into the army as were the Russians, but they hadn't fraternized with the Russian population, so had the language barrier. There had been 104 German villages founded in the years 1764 to 1767 and the population grew fast because each male child was allotted acreage at its birth, so from 1767 to 1909 they had to start new villages to accommodate the over population. In all there were 394 Volga settlements. Most Germans lived as Germans, refusing to become Russianized.

I was drafted into the Czar’s army in 1915 to fight the Germans in World War I. I was stationed in Constantinople, which was later changed to Istanbul, Turkey. While in Turkey, I saw Lenin make speeches from fire escapes on the sides of buildings to crowds of disgruntled Turks and including Russian soldiers who were trying to fight Germans with inferior weapons or weapons furnished by the United States and England because the Czar had thrown in with the Allies to stop the Kaiser in his quest for taking over Europe in WWI. The Russian army soldiers had families at home who were starved and abused, so had no desire to fight for their own government, not to mention fighting for strange allies. The Turks were under Russian rule at the time and wanted their own, so Lenin who had been living in exile in Germany wasn't bothered much making his speeches and soon the Russians returned home and helped their fellow countrymen called Bolsheviks, take over the Czar’s government.

They chose Alexander Krensky as President. They were still trying the free world system and Krensky was the one and only President ever elected in Russia, but couldn't please both the conservatives and the Bolsheviks and because of the wars damage and the economic breakdown, things got worse instead of better and the revolution then really went into high gear. When the Russian army returned home to overthrow the Czar, I went home to my village of Norka, to the family farm, hoping my army days were past. Lenin and Trotsky formed the Red Army to bring down Krensky, whose backers were the White armies. Each side would come to the German villages and requisition, or take supplies, horses and even men to help them in their cause, until finally the villagers who lived in the area that had the reputation of being the bread basket of the world, were abused and going hungry too.

As you traveled west from Schilling, you crossed the Karamysch River. The land east of this river belonged to the villagers of Beideck. The land from the river to Norka was called Oxa Grava and was our Norka grasslands, which was used for raising our hay crops for the winter feed of our livestock, and pasture. Going on westward toward Norka, were orchards, and gardens in the area called Norka Grava. It was an area lying on the right, or north side of the road between Karamysh River and Norka. In Norka Grava lived about twenty or thirty families, some of whom worked for a man named Pauli, who was owner of the brick factory built along the roadway. The people who lived in Norka Grava had to cross through the water to get into their yards from the road, or go around.

The flow of water wasn't deep along here, but was around knee high along the roadway. There was an access road by way of the gumno (threshing fields) without crossing the waterway. It started in Oxa Grava and ran around the north of the village. People would say, "Ich gehn uber die fahrt" meaning I'll take the shortcut, rather than go around. Pauli (also Pauly) bricks were made of materials on the site, and were mixed by two large paddles connected to a merry-go-round affair built into a round tank about 16 feet in diameter, pulled by a horse. The brick mix was poured into brick forms, and sun dried, until hard enough to handle without breaking, then placed into racks in open silo type bunkers about sixteen feet wide, and eight feet deep. They stretched in length about a city block. There were several bunkers of this size and they burned up a lot of waste in the bake process. When they were in the bunkers and ready to bake, the men piled any burnable materials into the pit, and set it afire. When the brick were baked properly, they were so hard, it took a hacksaw type saw to cut one in half. When baked they were stacked in neat rows along the roadway for sale. The rows of bricks stretched for blocks. On the south side of the road were pasture lands, where the herdsmen of the village brought the livestock to graze each day during good weather. The dividing line of cows, pigs, and other stock going out to pasture, was at the village courthouse, with the cows and animals belonging to villagers east of the courthouse, being driven to the pasture land east of the village. The livestock of the people west of the courthouse were driven to pasture land west of town, above Oberdorf (upper village). In winter, animals stayed in the yard or corral and were led to the creek, or strategically placed water troughs, once or twice a day.

The Karamysch River ran north and south between Beideck and Norka, but up north it veered or turned westward, so it bordered what was considered two sides of the Norka ground, the eastern edge and also the northern edge. Across the river on northern shore, was a Russian village named Rybuschka that we traveled through when going toward Saratov. On the southern edge of Norka land we bordered with Huck and Frank land. To the west we bordered with Russian villages on the Medwediza River. Along the Karamisch River, across from Rybuschka, the land lying along the river was owned by four parties. Bromundt, a Cossack with a large governmental land grant, beside him was land owned by Jost Henry Miller family, a parcel owned by Sinner family, also a parcel bought by the villagers of Norka from a man we Germans called Seifert, but known as Blauchen. This we used for our potato ground. These four parcels of land far exceeded the amount of land farmed by all of the Russian villagers of the village of Rybuschka, and was one of the most agonizing to the Russian villages near and far.

Norka was one of the original, or Mother Colonies, founded in Russia during the years 1764 through 1767. It was founded an August 15, 1767 with approximately 957 people. It lay on the Bergseite or hilly side of the Volga. It was a Protestant colony. By 1852, Norka had grown so large that many left to start the daughter colony, Neu (new) Norka. By the year 1914, our census in Alt (old) Norka was more than 14,000 people, but I for one feel that this figure could be somewhat deceiving. My reason for this is that many of our folk had left for the United States, Argentina, and Canada. Our families remaining in Russia kept some, if not all of these people listed as members of the family, because under the dusch system (a communal land allocation system also known as Mir), the land, hay, etc., was allotted to male family members, and over the years there were allotments sold to other family members, and even to strangers, when someone wanted to depart the area. I suppose the fact we were being pressured by the Russians for some of our land, was a good reason to keep our population census higher too.

Many of our neighbors, as well as my father in law, Dicker Helzer, sold their dusch (land allotment) when departing the area, but in the case of my father-in-law, who died in Minsk, his family returned to Norka, and the Bolsheviks made the buyer get off the property and return it to them. They insisted that only people actually living in the household were entitled to land, another reason was because the buyer had paid in Czar’s moneys, which the new regime didn't recognize. My aunt and her husband, Dach Grabbler Schreiber, had sold their dusch and personal property to an Adam's family in 1912, but when the Bolsheviks took over they nullified all such transactions that didn't include on-site owners. This meant that the Adam's were farming the Schreiber land shares, but had no people on the premises to cover the amount of dusch that they were farming, so the land was confiscated from the Adams.

The village was defined as Unterdorf (lower village), Mitteldorf (middle village), and Oberdorf (upper village), each portion having its own school, except for when we had to build the Russian school, which was used by all and located in Mitteldorf, across the road from the church, which was in the ninth row and the old and new cemeteries lay in the fields south of the church and schools in Mitteldorf. I attended Russian school for one year, after eight years of German, then was old enough to quit. There were nine rows of houses and buildings in Norka, and a short tenth row on the west end, or Oberdorf end. We had water running on both the north side of the village and on the south side. This was spring water, which came out of the hills above Norka on the west, and the flow on the south was deeper and called Ella Bahn, or Borne, and the water on the north was Grosse Bahn Quella (the large spring). The bodies of water came together at a point east of the village, where a dam was built, along with the bridge over it, and it is called Norka River on many maps. In the summer you could ford this knee high water some places. Most of the villagers were farmers, but as villages go, almost every village had a supply of blacksmiths, wagon makers, shoemakers, carpenters, and various other laboring people who weren't interested in farming for themselves, or may have used the farming for a part of their livelihood, along with a trade. There were actually people, who sold their dusch to people for cash, or had it farmed for shares and they did work for others.

Faiglers’ (Vögler) leather tannery was a big employer, and at different times of the year they hired as many men as the biggest flour mill owner hired. They bought hides, which were soaked in a solution to loosen the animal hair, and at just the right period of soaking time, they were removed from the 16 or 20 foot diameter vats of solution, and scraped clean, then placed into another rinse bath, then this was followed by a soak in a dye solution, for the color of leather that was preferred. During the revolution years, and when an animal sickness hit our village, so many animals died, that the Faiglers' couldn't handle all of the business, so many of us had to go ask for directions, which Mr. Faigler supplied, and we learned to cure some of our own hides. Mr. Faigler was considered a generous employer who gave schnapps breaks and a good noon meal to his employees.

Reicher (rich) Schleining owned a general merchandise store, had a mill, fruit and vegetable yards, and farmed land with about twenty teams of horses and oxen. He hired many people to run his enterprise, and also raised one of my uncles when my grandparents died of cholera in the 1860’s and my father and his three brothers were orphaned.

Heinrich Liehl (also Lehl), who was my brother-in-law, and nicknamed Rote Schintler, meaning he was redheaded, and a coat or belz (fur) maker, was known through most villages as one of the best leather coat makers in the colonies. He would be called to the best homes, where he stayed until he finished making the great coats for all family members, receiving free room and board, plus good wages for his work. He and my sister had eleven sons, and when she was pregnant with a twelfth child, the Czar sent a representative to our village and told them if it was a boy, they were to receive a gold medal for having twelve sons. It was a girl, and she died a horrible death at about age two, from drinking a lye solution left after the making of homemade soap. This was the liquid under the soap and used for scrubbing. It was actually a better cleaner than the soap.

There were four roads that ran through the village from east to west, and a short fifth road, which ran from the southwest corner to about the center of the village. These ran between nine rows of houses and a short tenth row. There was a wide road around the north side, which branched from the regular road from Schilling, at Oxa Grava and people from Oberdorf or Mitteldorf could by pass going through Unterdorf on this road, which sped up their trip home from Schilling, and also kept the dust down for Unterdorf residents. This was principally built for the purpose of hauling the grain right from the threshing area, gumno to Schilling, without having to take all of the wagons into the residential areas.

There were four springs which were actually all on the northern side of the village, spread from the east near Mitteldorf, the first was called Brills Bahn or Borne. The spring itself was almost a verst (about 3,500 feet) out from the creek named Grosse Bahn, but the water was brought through a flue to a bricked storage reservoirs built at the edge of the creek, so the overflow from the reservoirs ran into this Grosse Bahn creek. The people had built wooden flues from a type of hollow tree that was readily available in the early days. They also used these hollow type trees for funneling water from the reservoirs into their tank wagons. The second spring which was fed to storage reservoirs several blocks further west of Brills Bahn, was Grosse Bahn, and probably had the most water flow, which probably was the reason the creek itself was called Grosse Bahn. The third spring which was flued to the creek edge in Oberdorf might have been called Lippardts Bahn, but most people in Unterdorf referred to it as Fatza Bahn, and anyone I ever asked about this springs name, laughed shyly, then gave me this name, but none knew why. Above Oberdorf was a fourth spring, which was also flued from where the springs came out of the ground, to a couple of storage reservoirs, with the overflow going into the creek. As stated before, the actual springs were further out in the land, with the water diverted to the reservoirs at the edge of the creek, otherwise what was the gumno area would have been all muddy roadways to the springs themselves, which would have ran down to the creek over the ground.

In the Oberdorf was a ravine which was called Gassa Grava (goat canyon) and was about two or so city blocks wide and impassable by wagon. It ran north and south through the nine rows of homes, and the short tenth row started at Gassa Grava and ran from there west to the end of the village. The through traffic went on a road around the ravine on the south side between the ninth and this short tenth row. On the north side the folk traveled around the ravine on a gumno (threshing area) road.

The third church was built in about 1880, and the lumber for it was sawed and hauled from Schilling. The upright timbers were hauled to Norka, setting on three large wagons, one behind the other, similar to what a log truck and tagging trailer look like today. The debarked timbers (like telephone poles) were rolled onto a specially built crib where a man standing on the timber could stand and saw, while a man beneath handled the other end of the long two man saw. They halved the poles lengthwise, then stood them in holes forming the church walls, similar to how pole barns are built. They placed the flat side out and the rounded side was facing into the interior of the church. They built a Lammastahn (rammed earth blocks) foundation between the poles, as the foundation for the wooden floored church. It was large and beautiful. A man from the village of Anton made the hollow boxed metal cross, and hauled it to Norka, where he painted it and the villagers turned out to raise it into place. The steeple was built with a slot to drop the heavy cross into at the peak. The man hooked a block at the peak, and passed a rope through it, with one end of the rope tied to the cross, and the other through a block anchored in the schoolyard next door. The people standing below pulled on the rope until the cross was up to the block on the steeple, where the man guided it up and into the slot that had been made for the cross to slide down into, then it was fastened securely, and all of the villagers participating in the festivities had a celebration giving thanks to the Lord for the accomplishments. This was the fact related to me by my parents and Aunt Lena (Derr) Weidenkellar, who were there at the time.

The Glocke Stuhl (bell tower) was on a lot next to, and behind the church, and was about thirty-foot high with three large bells. The bells hung in the top of the structure and there was a platform built about halfway up in the structure, where the choir could set to sing at festive occasions. The large bell, which weighed over three hundred pounds, was said to be audible for a distance of five versts. It was rung continuously when there was a snow blizzard or heavy fog and people were known to be out of the village after it turned dark. The pealing of the bell led many folk home safely when they were lost in a snow blizzard. There were bell ringings for summoning folk, for spontaneous meetings, for fire alarms, for church services and funerals. Volga Germans were great on bell ringing. In case of fire anywhere in the village, it was required that anyone seeing a fire start running toward the bell tower yelling "fire, fire" at the top of their lungs, this causing someone several blocks closer to the bells to yell it, then they take up the run. By this method the alarm was relayed to someone who could ring the bell although had no idea where the fire was, but the alarm was in before the original person moved more than a block or two. There were people in various parts of the village who kept wagons or carts handy for fire fighting, with pales, axes or other equipment such as ladders. If they got to a fire and controlled it with their efforts saving a lot of damage, they were rewarded greatly by the Gemeinde (elders of the town council).

Two of the older Norka schools were replaced with new ones in about 1915. One in Oberdorf, and one in Unterdorf. The new and larger Russian school had been built next to the church in 1905 when we were ordered to learn the Russian language along with the German we had been wholly learning previously. The old Unterdorf school in my school days had been known as the Kaiser school. It was because it was located next to the property of a family named Kaiser. Old timers who came to America still referred to it as the Kaiser school. In 1909, when I went to the Russian school in Mitteldorf, my teacher’s name was Hill. He was referred to as Gigl Schnitter (Note: probably Gickel Schnitter or chicken catcher). I attended for about a year, then just stayed home and helped do the farming and hauling merchandise to help support the family. The most affluent of the village would send their children to Saratov to boarding school, where they learned both German and Russian. They were then capable of getting good employment, in cities, or higher positions in the Russian military.

We had a hospital built in 1904. It housed a Jewish doctor and a Russian dentist. Previously, our needs were handled by local people with medical sense or we had to travel to Balzer or some other village with a doctor. The new hospital was on ground east of the old cemetery, and out the south edge of the village on the road that led to the Huckere Bridge, which we had to cross to travel to the village of Huck. This ground was referred to as Reides Bahn Felte where the villagers held an annual sale, similar to the flea markets of today. It was referred to as Jahrmarkt (annual market). Nearly everyone brought things to sell, and people came from other villages to buy things we were selling. People like Mr. Faigler, the leather tanner, set up booths loaded with tons of leather goods, and the Russian buyers from other villages usually bought out all of the red dyed leather quickly. Katza (cat skinner) Sinner brought caps made of hides of lambs, cats, or wild fur bearing animals. Besides buying cat hides and such, he skinned birds and feathered creatures, which was used for ladies finery. Katza Sinner was the noted village taxidermist. The sales lasted a week and you always bought more than you sold, unless you were the exception. The Jahrmarkt was held in the month of October.

The highest point of the village was just north of the northeast corner of Krieger’s private bridge. From the top of rise you could see roofs of most houses in Unterdorf. The ground sloped downward toward the south, and the low brushy area on the southern edge was called Weins Grava and was actually outside of the village rows of houses, but included in all village census and activities. The roadways and houses of Weins Grava were scattered in gullies or ravines east to west, rather than rows of houses as in the village rows. The village stone or rock quarry was just across the Huckere Bridge and down a steep incline to the right side of the roadway.

Norka, Russia - Remembered by Conrad Brill

Every Thursday the villagers of Norka held an open market, or street market. There were booths set up in the first row from the courthouse east to Faigler’s leather works. People brought food and wares. Tinkers or traveling salesmen brought merchandise too. Biggest selling items were usually roots for tea, (sweet wood) rice, and Hirsche (pearl barley). Hirsche brei (also Hirsebrei - a millet gruel) was most people’s breakfast. We villagers raised some gardens, but generally we specialized in grain, which we sold, then bought things such as tomatoes, watermelons, tobacco, fish, rice, and many of the everyday things people nowadays have the idea we raised ourselves. People on meadow side of Volga had better earth, so raised more items themselves. Even sunflower seeds, we bought mostly from Russian peddlers. In about 1905, the Russian people were so disillusioned with their government that bands of Bundofschieks (rebels) raided stores owned by Jews in the Russian villages, where they threw the contents out into the streets where others carried the things away. Many Jews were beaten to death or maimed. In another such episode at that time, a Norka family named Hefeneader who owned a mill in a Russian village, were killed and their mill burned by a band of Bundofschieks. A family friend, Adam Schwartz, employed by the Hefeneaders hid in a bedding drawer, which slid under a high bed when the shooting started, so wasn't found. He later related the events to our village elders, who sent wagons of Hessler family, Schnell family, and our family, to go move what was salvageable from the Hefeneader property that was destroyed. The Hessler's, who were neighbors of ours, were related to the Hefeneaders (Hefeneider) and Garte (Garden) Krieger’s wife was their daughter.

In the first row of Unterdorf near Garte Krieger’s private bridge and driveway lived several families who were herdsmen of Unterdorf cattle, sheep and swine. An old man named Schleuning (also Schleining) who had worked for old Mr. Peter Sinner at the mill when young, was a sheepherder. A man named Dinges was a cattle herdsman. An old man named Brill was a shepherd. These three families lived at the outer edge of Unterdorf in the first row between Hoota Grava and Garte Krieger’s bridge. A lot of younger men herded the swine and a great story always concerned the young man who always did a good job of keeping the swine out in pasture unless he had a date on Friday or Saturday night, at which time he was notorious for getting the swine back home hours early. One man got distraught over this and one day cornered the young man at the gate when he brought the pigs in early and inquired why the pigs were being brought in at this early hour? The fast thinking young man said, "the pastor’s pigs are full, so it's time we brought them all in." Herders were paid in cash or products by the animal owners.

The affairs of the village were handled by the Gemeinde which consisted of one senior member from each household. This was the large Gemeinde, which usually entered into big, long, bitter, all night sessions on the pro’s and con’s of most village affairs. If they were stalemated, there was a small Gemeinde of businessmen, Vorsteher (mayor), Schreiber (secretary), schoolmaster, and preacher, who then decided the issue. Before Reverend Wilhelm Staerkel was retired though, he had unprecedented power given him by the Winska Na Schelnic (the highest Russian official in Saratov). This man came to Norka in the first automobile I ever saw, in about 1903‑05, for a meeting with the pastor, and we little boys chased it from the Russe Bruek (Russian Bridge) to the Grashaus (courthouse). Reverend Staerkel wore this gold medallion attached to crossed leather straps, which fit over his shoulders and crossed under the medallion in the center of his chest.

Our schoolmaster, Carl Leonhardt, who replaced Lehl was also the church organist and choir director. He was the finest organist I ever heard play, and we had such a huge set of pipes for our church organ, that the largest was about the same diameter as a skinny man. He was fired by Reverend Staerkel years later. He was supposed to have gotten a young teenaged girl pregnant. He was then replaced by another Leonhardt (Sasha) who was also from Grimm where Carl had come from. They were probably distantly related too. The younger Leonhardt came to the United States in about 1970 or so to visit relatives and friends in the Midwest, Oregon and Washington. My wife and I went to visit with him. Upon his return to Russia he was very helpful to our nephew in Siberia, with paperwork and advice, in the nephew’s visit to us for three months in 1972.

There were lime pits out on the land around Norka, which people brought in to use for making a stucco finish to their houses. We had a rock quarry‑gravel pit across the Huckere Bridge going south out of Norka toward Huck. The ingredients at the site of the Pauli (also Pauly) brickyards on the eastern edge was ideal for brick making, so it was built there on the site. Many people raised sugar beets, which they then boiled into heavy sweet syrup which we used for sweetening like you do granulated sugar today. In the earlier days of Norka, there had been large trees and underbrush around the village, but by the time I was born it was pretty well cleared of large trees. However, we did have brushy ravines to the south of the village, and several that ran north along the roads to Rybuschka and villages to the northwest.

The preachers we had that I know of from family discussions start with Reverend Bonwetsch, who watched Wilhelm Staerkel as a youth playing the game of that day called Gausa. A game where you tossed barnockels (chestnuts) taken off the legs of dead horses, and played somewhat like marbles in later years. He took Staerkel and had him schooled to be a preacher, and Staerkel later married Beate Bonwetsch. When Reverend Staerkel became senile they put in Reverend Weigum and semi‑retired Staerkel. When Weigum left we got a young Reverend Wacker. My grandfather used to tell me how good Staerkel was at playing Gausa, and how Reverend Bonwetsch always remarked that "Willie" would make a good preacher for Norka. Reverend Staerkel had come to the United States in the 1860's, as well as Jerusalem. He was instrumental in villagers leaving Russia to come to America, as well as organizing the Brethren of the Versammlung. While I was in the army, he became lost in a snowstorm between Huck and Norka, when he wandered off toward Huck, rather than go to the church in Norka to assist Reverend Weigum with communion. He hadn't shown up at the church and when they sent for him, his daughter said he had left hours ago. They found him and he survived, but died of natural causes before I got home from Turkey.

Konretja Brill

I was the youngest of the seven children of George Brill and Elizabeth (Derr) Brill. As with my brothers and sisters, we were all born in grandpa Derr’s house. My eldest sister in the late 1870's, followed by three brothers and two sisters, then me in 1895. The grandparents Derr had six girls and no sons, so under the dusch system, where each male child born was given a parcel of land, the Grandparents Derr were in a desperate situation, as they had eight family members and only one parcel of land. My Brill grandparents both died of cholera in the 1860's, leaving four sons orphaned, so the four sons were raised by other families. My dad, George Brill was raised by the Philip Hertes (Harts), his mothers parents, in the village of Huck. When he grew older he left Huck and returned to Norka. He hired out to the Derrs and eventually married the eldest daughter. Generally when a couple married, the woman would move into the husbands household and share work with sister in‑laws, while the mother in law oversaw the daily tasks. Since dad was without parents and a household he lived with the Grandparents Derr. This situation worked well for the grandparents Derr because they were able to obtain more land after my parents had four sons and three daughters born into the their house.

The ladies of the house changed chores each week, unless they preferred certain tasks and agreed to do that chore regularly. When fieldwork was at a priority, all hands fell to that task before any other consideration. Grandma and one female could run things at the house in the village, while everyone else camped out on the ground at the planting or harvesting site, until the task was complete, except to come into the village Saturday night, so as to make church on Sunday. Almost everyone had to make church on Sunday, if only to impress the neighbors. A lot of people, who were shorthanded on help, could hire girls for 20 kopecs per day for threshing grain and such. Several neighbors would haul wagon loads of Russian girls to their fields to help with threshing. These girls would sing and work all day.

My three Brill uncles lived in Norka and had families there. My dads nickname was der Hucker Brill, because his Herte grandparents had raised him in Huck. His brother, Uncle Conrad, was raised by a Schleuning (Schleining) family, who had vast land holdings of fruit orchards and vegetable gardens and also owned the Schleuning’s Mill and Lafka (mercantile store). They were referred to as the Reicher (rich) Schleining's, so Uncle Conrad’s nickname was der Reicher Schleining’s Brill. Uncle Philip Brill was raised by a woodsman’s family and was always called Bilschiek (logger) Brill. The other Uncle Heinrich died while I was only five or six, so wasn't around for me to learn who raised him, or what his nickname was. I do remember going with my mother as a toddler, to visit her and their only son, who was also named Conrad as I was. He was about ten years older than I and mother and I went to see them and wish them a safe journey when they left Norka to go to America with her new husband named Gerlach, in about 1905.

My Derr aunts all married in Norka and later came to America, except for my mother and dad and a younger sister named Dimbet, who married a Schleining, who was younger brother of Jacob Schleining, who married my sister Elizabeth and came to Portland Oregon in 1906. One of my Derr aunts had a child out of wedlock, about the same age as my older brother. When she married a widower with three daughters, the widower refused to accept her child, so the grandparents Derr raised him and had him of naming children, which went on in those times. I had a brother Conrad, born November 15, 1889 and he was named after our Uncle Conrad. I was born in 1895 and named Conrad after our cousin and uncle, Conrad Derr. In those times, it usually worked out that older parents having children would die before getting the younger ones raised, so you chose a Godfather who would step in and raise the child, and you honored him by naming the child after him, so we had Conrad, then I was Conrad, but to be called Konretja, to keep us separated name wise.

My childhood was relatively happy until after grandmother Derr died. I usually spent most of my days with grandpa Derr and he as head of the household did only the lighter tasks and lots of visiting around the village, which irritated my older sisters, as I hauled water, harrowed seed into the fresh worked sail, to get it baptized as Conrad Derr and when I was baptized, he was my godfather. This is a good place to explain the custom covered before the birds landed and ate it, and went with grandpa on many occasions, while they were out doing heavy fieldwork. Grandpa, like most older people, got lonely and talkative on most of these occasions and would tell me all about the village, it's older inhabitants and what life was like when he was, growing up. We hauled water from centrally located reservoirs in water wagons, which we could use in winter with sled runners instead of wheels.

Twice a day during farming season, we would ride a horse and lead the rest, to a creek, or to the watering troughs around the village to let them drink. In the winter we usually only did this once. We kept most horses inside a corral in the winter, unshod, except a team with ice shoes, which we used to pull the water sled. In the summer we also took the sweated horses to a river and swam them, to clean and wash the salty dried sweat off their bodies. When I harrowed seed into the ground, I was usually on the back of a horse pulling a harrow and tied behind was another horse pulling a harrow and sometimes a third horse, because the seed would surely be eaten by birds if you didn't get it covered almost as quickly as the women hand broadcast it onto the ground. Grandma Derr died about 1902 and then life would take a dramatic change for all of us. We were hauling manure to the fields the day a neighbor girl rode out on horseback to inform us that grandmother had died.

When grandma died, the well-meaning friends from church and prayer meeting talked grandpa into marrying a younger widow with a sixteen-year-old daughter, from the village of Huck. Things quickly turned bad, as my mother was then eldest female and rightfully should have now been head of the house; instead she had a stepmother younger than she was, with a daughter who quickly married Conrad. Gosshorn Derr, the grandson whom Grandpa Derr was raising as a son. My parents decided that it would be best if we now had a home of our own, rather than live in this pressured atmosphere, especially after the males in our family being the main reason Grandpa Derr had accumulated his worldly goods, not to mention over 25 years work, and with him raising the son of a daughter as his own son, that child would eventually inherit everything according to laws then. My father bought a dance hall from Dicker (rotund) Helzer, who had used it for the week long day and night harvest celebrations each fall, and as it was at harvest time, we had one more harvest festival in it, then dismantled it and rebuilt it into a house for our family, on a spot with a shack where a widowed shoemaker lived. My eldest sister had married Heinrich Rote Schintler (redheaded coat maker) Lehl and wasn't home with us anymore. There were divisions of implements, wagons and horses and such, but it was hard on everyone concerned, especially me. Now I didn't see much of grandpa, my friend, and when he did come over and complain to my mother that his younger wife wasn't all he had hoped for, my mother was very short with him and quick to tell him that there was no fool like an old fool where younger women were concerned, so I didn't have many more great adventures with my friend and companion, Grandpa Derr. To make it worse, the few young male friends who lived around Grandpa Derr were also to be missed. Gruen Hannes (John Green) was a boyhood friend, but his parents moved away to another village too, so I had to make new friends at a new location in Unterdorf. I got the measles while the house was being built and we lived in the shack on the property. It was the sickest I can remember being in all of my years in Russia. I soon made friends at the new neighborhood, and went to Unterdorf’s "Kaiser" school. So named because it was next door to a family named Kaiser and I remember the man being referred to as Deffe (deaf) Kaiser. My closest friends were two Krieger brothers, Henry and Alex and Adam Hahn, with whom I kept up our friendship from Grandpa Derr’s neighborhood. Adam was the son of Heinrich (Henry) Hahn, who had about five other children, some of whom were already married, with children. The people called Adam, Saltzman Hahn. It was said that old Mr. Hahn was too old for sex and Saltzman was a peddler or tinker who came to Norka peddling housewares regularly, who used to park in the Hahn’s yard during his stay in Norka and he was the biological father of Adam. Nobody ever denied it, and when I met some of Adam’s nephews later in United States they never even knew they had an Uncle Adam, so I am sure it was true and the married members of the family ignored Adams being born into the family. The tragic part is that most of the grown-ups called him this to his face, as did older children to humiliate him.

Some of the exciting things happening about this time, was when we boys saw our first automobile. It came into the village over the Spady bridge, so called because a family named Spady lived there when it was built over the Grosse Bahn at that spot, but Spady had since moved, but it was the road you left Norka on if traveling toward Saratov. We boys chased it all the way to the Grashaus (courthouse) where the Winska na Schelnick (territorial governor) sent word to get Reverend Staerkel, which was done and that was the first time I ever saw anyone else in charge over Reverend Staerkel in my young life.

One day we even had a German pilot fly an airplane over the village at a low altitude, and for years the people talked about the fiery man who flew over the village. He was so low you could see his teeth as he waved, while the exhaust belched smoke and noise all over the place. We had a lot of friends, relatives and even family leaving for the USA, Canada and elsewhere while I was a boy. Usually they left for Germany or Belgium from there. Reverend Staerkel had been to America and was instrumental in encouraging many of our villagers to make the move to the Midwestern States for continuing farming in the USA. People leaving at this time, would sell their dusch to a relative or friend, for almost what a ships fare was, then that buyer had that land share, as if he had another male child. I believe that this was really illegal to Russia's laws, but our authorities kept the departing villagers name an the village census to insure that we wouldn't lose any of our land to the neighboring Russian villagers, who were clamoring for land, because they had an overpopulation of people, but a shortage of land, since they arrived after our villages were laid out in the early days, after arriving from Germany. My sister Elizabeth helped take the census in 1902 and I don't think it was taken again until 1914, so I know that we kept farming our male shares after two brothers had left for United States. and an aunt and uncle sold theirs to an Adams family in 1912/13. After the revolution these sales were null and void and only people, male and female, living on the premises, were allowed shares of land, which really hurt the buyer, who had made purchases of four or five dusch, just before the revolution.

Many Russian peddlers came through Norka selling produce, fish, tobacco, woven cloth, watermelons and almost anything imaginable. On occasion the peddlers would have several of their children in the wagon with them. Maybe to put you in a buying mood because you saw he had children to raise. We would stay out of eye sight of the Russian parent and also our own, but when we got the eye of the youngster, we would scratch under our armpits imitating monkey or ape, then they would rub their finger under their nose, or pinch their nose with finger and thumb. We relayed to them that they had cooties or bedbugs, while they got back at us meaning we stink. For entertainment we played soccer, flew kites, swam, or went down to Schmier Bossum (grease smeared busom) Burback's fruit orchards copping fruit when it was ripe. We used to walk through the orchards to get to the swimming hole, so we knew where the different fruits were and when it was at it's best. One day we saw workers picking, so we gave the orchard a wide berth and stayed on the road. The foreman waved us over and asked us if we didn't want some good ripe pears. We were amazed and said yes, and he even helped boost us up a tree nearby. We should have been suspicious, as he was carrying a beekeepers hood. When we got up the tree he threw dirt clods at several beehives under the next tree, getting them infuriated and we boys had some real welts by the time we got out of the area.

In the winter we played hockey on frozen ponds and had sing-a-longs in houses. The cows and horses stayed in the corral all winter, so we had to walk them to drink at horse troughs sat at different locations throughout the village. I would tie several together and ride one. When they were being worked we watered them several times a day, but in winter once or twice, usually in the morning and again at suppertime. We played tricks on people too, usually on old folk who had nobody around to give us a swift kick for bothering the old-timers. We had an old lady who spun thread, and she sat with her back to the window on the street-side, so the setting sun would give light an her work. We took a long fine metal drill bit and worked a hole around her window casing and she kept a halved wooden barrel full of a mixture she would dip her fingers into at intervals to make twisting the material easier. We put a long metal rod through the hole and tipped her container over when she was engrossed in her spinning. Of course we got out of sight and stayed away from her house for several days after.

There were people who trapped wild canaries out in the threshing fields in early spring when there was still snow on the ground. They made packed snow trough, which they seeded with handfuls of grain and maybe some raw side pork. They layered horsetail hairs back and forth over this bird bait then left, so they weren't seen. When the wild canaries landed in the horsetail hair and started eating, their feet became entangled. Sometimes they could get several before they could untangle themselves, but it seemed they always had a house full, which they raised for hatching and selling as household pets in the neighboring village sales.

We had an old neighbor named Vetter (uncle) Ludwig Reisbick. He and his wife had several children who had left Norka and had gone to the USA. They were real nice friendly people, and old Vetter Ludwig loved wild canaries and their singing. One day he was coming in from the pasture lands just so thrilled by the bird singing he had heard on his walk. He elaborated it and the songs of the birds to my mother and all he met. Our neighbor Vorsteher der Rupe Kleiber was working in his yard, and when old Vetter Ludwig left after the bird discussion, he called us four boys over and gave us several kopecs for candy and told us to keep out of sight, but if we saw Vetter Ludwig outdoors, we should hide and imitate the wild canaries. We did this strenuously for several days, keeping the old gent running from one side of his yard to the other trying to see the birds. I think Vetter Ludwig was Klieber’s father in law. One night we went into the barn and caught several sparrows, which we took over to the Reisbick’s. They were baking squash and had a table full cooling when we got there. They invited us in when we knocked and we turned the sparrows loose without their knowing we had brought them in. They asked us to help them get the birds out and while we chased the birds, Adam held the door open and also proceeded to snatch a half of squash and set it outside. Mrs. Reisbick had seen him and said "Vater, Vater," (father, father) he just stole a squash. The old gent said, "let it be mother, the boys are probably hungry too." This made us ashamed for a few days, until we caught more sparrows and dropped them between the double panes of window glass in a window that had a broken corner and the birds drove the old couple wild trying to get the birds out without taking a window out. Old Vetter Ludwig had the nickname of Flopjer (flapper) Reisbick. They had a dog which had rabies or foaming at the mouth, and they were trying to pen it up before it bit someone, but the dog wouldn't get into the pen, so they wound up chasing it all through the neighborhood trying to get it home and penned. Neighbors coming out to help laughed at old Vetter Ludwig running down the street with a big leather belz (sheepskin coat) on, with hands in the pockets and waving the coattails like a bird flapping it's wings. Mr. Klieber said, "look at that old flobjer, and so that nickname was used for Vetter Ludwig as long as I knew him.

Reverend Wilhelm Staerkel was probably the most powerful authority in Norka and our neighboring villages. He was born in 1839 and died in 1915. He wore a huge round medallion, mounted on crossed belts on his chest, for official meetings. This was bestowed on him by the territorial governor in Saratov. My Granddad Derr told me that when Wilhelm Staerkel was a boy, they always played Gausa. It was similar to marbles in this country, but the barnacles, or chestnuts (toes), off a dead horses legs were used, and they were thrown rather than shot like marbles. Reverend Bonewetsch used to travel the circuit preaching and he was always watching the Gausa tournaments, which Wilhelm Staerkel usually won. He always made the statement that, "that Willie Staerkel would make a good pastor for Norka." He later took him from Norka and got him involved in his pastoral life.

We had a schoolmaster named Lehl, who had gotten into some problem, which led to his dismissal. The population was against the dismissal and asked for a town council meeting, at which they decided to reinstate Lehl. When Rev. Staerkel heard of this, he instituted another town council meeting, at which he wore his medallion, and when he stood, he took hold of his crossed belts with both hands, shoving the medallion forward with his two thumbs and said, "I said this man is discharged, and so he is, and if anyone wants to disagree with my order, I will send him and the schoolmaster both, to Siberia." The schoolmaster was fired and nobody stood up to argue the point.

Rev. Staerkel and his wife, I believe she was born Beatrice Bonwetsch, never had any children. One cold night their housekeeper heard a faint noise on the porch, so opened the door and found a snuggly wrapped little baby girl in a basket. The Staerkel’s raised that girl, who was about my age and they named her Hulda. She was alive and caring for her aged father when I left Norka to go into the Russian Army to Turkey in 1914. They say that Reverend Staerkel became senile, so in a way of speaking, they defrocked him, bringing in a younger Pastor Weigum, whom Rev. Staerkel would assist at times, by sermons in Huck or nearby. Reverend Staerkel was to assist Reverend Weigum for confirmation but didn't show up, so the Reverend Weigum sent someone to his house looking for him, and Hulda informed them he had left hours earlier, so they sent out a search party and discovered him wandering in the area between Norka and Huck. He was very ill from this experience, but survived. He did die before I came home from the war, but he had confirmed me, married me and my first wife Anna, and had given me my last communion before I left for the army.

School was always secondary to the work of farming. We attended if we weren't needed for farm work. I missed more school after Grandpa Derr died, and also got into heavier work. Rupe Klieber’s son needed a wagon and teamster to haul a load of eggs to Saratov, which he could sell out in a few hours on a street corner. I was only nine years old, but I suppose because Klieber’s son was married and living at home, my folks spared me to drive the team, knowing he was adult enough not to leave me get fouled up, and besides if they just loaned him a team and wagon our family wouldn't get compensated. We layered the wagon bottom with four or five inches of straw, spread a canvas over this, then covered the whole canvas with eggs packed so tightly they couldn't bounce or roll together. Over this we placed another four or five inches of straw then canvas again. This we did until the egg load was to the top of the wagon sides. We then covered the eggs and put on a canvas we tied tightly to the wagon sides and drove it to Saratov, about 60 kilometers away. When we uncovered them and sold them, we lost less than a dozen by breakage. The next fall, a lady from Saratov came to Norka and bought a wagon load of potatoes and hired our wagon and me to haul them to Saratov for her. Dad got five rubles for the haul, while I had hours of misery during my drive home through the Kasacka Wald (Cossack Woods) an area where many passers by were robbed and murdered for their belongings, between Rybuschka and Saratov.

Bloody Sunday

In 1902, when Jacob Schleining was courting my sister Elizabeth, she had a suitor named Weisel (Whitey) Schlidt. He was always trying to be her favorite boyfriend, but she preferred going with Jacob Schleining. Whitey and several of his friends would lie in wait for Jacob after he left our house and rough him up. He was from Oberdorf, and boys from there weren't looked on in favor by the boys from Unterdorf. It was the same the other way too, because my brother Johannes, was always picked on by his girlfriends uncle up in Oberdorf, when he was courting Katherine Sinner, daughter of the taxidermist, Katza Sinner. They too later married, but her uncle never treated Johannes as an in-law. It got so that Grandpa Derr used to walk Jacob Schleining halfway home. He was a big man, and the bullies never acted up when he walked with Jacob.

My oldest brother, George and his wife Louisa Schnell left Norka for Portland, Oregon in 1907. Some of our relatives already over, wrote back and said, "over here they pay you a dollar a day to lay on your back greasing railroad cars, and you can live in town without farming. They gave me their spotted dog and left, so I had my own pet. In 1906, my sister Elizabeth and her husband Jacob Schleining with their daughter Katherine had left Norka for Portland also. They left during the snowiest and coldest storm I can ever remember us having in Norka. They had wanted to leave in about 1903, but Jacob’s father went to the Reverend and the Gemeinde and claimed he was needed at home to help his parents farm the land, so permission was refused. Soon after, Jacob was drafted and sent to the Russo‑Japanese war. When he got back from the army, he went to the town council meeting and stated that he had been refused permission before because of helping his parents, then he was sent to the army where he was no help to the parents, so now he was getting permission, or going to the Russian authorities in Saratov. He got the permission and passport and they left.

We hauled our grain to Schilling, a port city on the Volga, where we sold it to buyers at the docks where barges lay waiting. During poor yield years there wasn't much problem selling, but when the grain was plentiful, the buyers would get together and make a pact to reduce the prices we got. Six or eight would lie around acting indifferent to whether or not they wanted to buy, which panicked the farmer who hauled it such a long way and didn't want to take it back home. After fleecing you on the price, they put it aboard the barges, which hauled it to Germany, or other parts of Russia or other countries. We could buy a load of watermelons from barges in Schilling for one kopec each. Usually we would fill the wagon with watermelon or lumber for the trip back. Our family hauled many loads of freight back for Julla Spady who owned a mercantile store and had all his wares hauled, rather than own horses and wagons.

We had four large storage bunkers in Norka, which were community owned, where the next seed crop was placed and enough surplus to carry over shortfall people. You could borrow from the surplus if you ran out in your own grain bins at home, then repay at the next crop. Many single men who owned a dusch didn't do any farming. They sold it and worked for wages. An orphan male was easy to place with a relative, or friends, for his land dusch. Girls were not as lucky and usually were placed where they were over worked for their keep. In earlier times there was an orphanage in Unterdorf, called Tantas Haus (aunties house) but it was discontinued and the council rented the property out. We would submerge watermelon into the grain in our family bins, to keep over into late year. We made watermelon syrup and sugar beet syrup, which was canned and used as sweetener, like sugar in the winter.

On the Bergseite (hilly side) of the Volga, we didn't raise everything ourselves. Instead we raised grain, which we sold, and some garden, but most of our vegetables and needs were bought in other villages, or from peddlers coming to the village sale each Thursday. There were Russian fish peddlers who came through selling smoked, salted, or fresh fish. The Russian peddler would rather trade goods than sell for cash. You could get three fair sized fish for an egg. The peddler would yell that he had smoked fish to sell, and we youngsters would make raids on the family chicken houses before the mothers knew the peddler was in town. When he was gone, we would gather at a favorite meeting place and eat smoked fish.

We had a man named Karamysh Miller, because he had a mill and pond on the river, where he had hundreds of ducks and geese on his pond. Occasionally he would see a duck taken under water, never to reappear. One day he came into Norka about noon with his buggy, containing the biggest fish I had ever seen, a Hake. It's tail hung over the tailgate. He hauled it up to the Grashaus (courthouse) door to display, because nobody had believed he had fish in his pond that could swallow a duck in one gulp. He had patiently watched, then shot it with a shotgun as it grabbed a duck. This man lived in Norka, near the courthouse, but made his living with his mill on the river, grinding flour for Russian villagers nearby. The fee for grinding flour was generally a big scoop for each pud (about 36 pounds) ground. The mill workers wore still leather coats to keep the dust out of their clothes, and a tricky scooper could scoop almost another scoop into his leather sleeve with each scoop, causing many unhappy customers and leading to many farmers dislike to a certain scooper. This was another practice the Russian government stopped after the Revolution. The farmer paid cash for grinding, and the miller bought grain from the farmer for cash.

A family named Hefeneader (also Hefeneider) lived in the first row in Norka, at the Unterdorf and Mitteldorf line. For years as a boy I heard gossip about how they got their wealth, so I always consider that part of it as a ghost story, but their death, later on, while I was a boy, and described to our villagers by a family friend, Adam, Soie ohmer schiezer Schwartz, was a truly tragic ending. The Hefeneader's neighbors, the Aschenbrenner's, used to tell that back in the 1860‑70's, a Russian peasant came to the Hefeneader's door on a cold rainy night, seeking food and shelter. They fed him and gave him a place to sleep in the cellar. At that time they had a poor mans home like most of the neighboring villagers. What I can remember of the home in 1905 era, is a beautiful brick place, with brick or cement block outbuildings, a building with hewn, notched logs, (log cabin style) all with metal roofs, which was a sign of wealth. The place also had a solid wood fence around it, covered with metal. The story was that in those earlier days, the Hefeneader's were rewarded by this peasant, who stayed on with them, with money he made for them in appreciation far the food and lodging. As the story went, he had just been released from confinement for counterfeiting and supposedly had treasury plates or counterfeit plates in his possession. He was supposed to have made money for them, but was ready to leave, but they decided to keep him as a secret prisoner, forcing him to make more money. They built the nice brick home, then the outbuildings and fence. Later they built a flour mill in a Russian village near Saratov. Mrs. Aschenbrenner could tell for hours of the trips from cellar to house the Russian must have made dragging chains, which they could hear rattling as he was hauled back and forth in the night. She said he must have died and was eventually thrown into an old well and the log shed built over it when he died.

In period about 1905 to 1909, when the Russians peasants in the cities were raiding and looting the Jewish stores, sometimes burning them, a group of Russian bandits rode into the mill property shooting all of the employees and the old Hefeneader couple too. Adam Schwartz was there working for them and was in his bedroom getting dressed when he heard the hoof beats of the riders coming into the yard, then screaming and shooting started, so he crawled into the bedding drawer under the bed, pulling a quilt down over himself, so he wasn't discovered. He walked back to Norka to inform our village councilors of the raid, and they sent three wagons to go to the mill and bring back any salvageable property they could. My brothers John and Conrad took a wagon, as did a neighbor Hessler, who was a relative of Hefeneaders. Garte Krieger was married to the Hefeneader's daughter. The home of the Hefeneader's was taken over by the Russian government and used as the State owned liquor store after the death of the old couple. It was situated next door to the Aschenbrenner’s home.

We had the Sinner’s Mill, which was the busiest of the Norka mills. It was electrified and powered by two large turbines. Mr. Sinner had proposed to the village Gemeinde that he would electrify the main cross street through the village, from the church to the courthouse, if they would put up the poles and wires. Several of the more influential members were against it, stating that Mr. Sinner was trying to make easy money through his electricity and many people who lived away from that area decided it wouldn't help their neighborhood, so why go through the work and expense of making a better situation for the neighborhood of such a few people. I don't know when the Sinner’s mill was started, but on the top of the highest part, (about four or five stories) was the year "1899" painted on in big black numbers. I assume that is when that high part was built, as Norka was 132 years old by then. Sinner’s family also had a newer and more up to date mill at Goschgoverna, on the Medwediza river, which had conveyor system, by which you brought your grain in bags and the milled flour came back in bags, via the conveyor. In Norka, we still used the old wagon box system. Two boxes fit into a wagon bed and when you took the grain to the mill, you had to manhandle the boxes with mill hands and yourself, pushing them onto the dock. The grain was milled and put into the same boxes, which had to be reloaded by manhandling. They milled 24 hours a day during the busy season, and someone had to stay with your grain boxes to help with loading and unloading and to see that none of your grain was stolen.

On the 11th of November 1909, when I and my brother Conrad were going home in the early hours of a morning, after spending the night at the Sinner’s mill getting our two grain boxes of grain ground into flour, we heard the storm‑fire bell ringing, and saw the flames of a large fire in the area where our Uncle Philip Brill lived, so we headed in that direction to help fight the fire. There were rules set down by the town council in the event of fire, so we and many others went there. The fire was at an old couple’s house, Mr. and Mrs. Johannes Bogler, who made brushes, combs and items of this type, using pig bristles, horsehair and such. The people assembled fast and got the fire out, which led to the discovery that the old couple had been killed and robbed and the fire was set to burn up the evidence and signs of the crime. The old man was discovered dead in the horse shed attached to the house, where he had been harnessing the horse to drive his wares to a nearby village, while the lady’s body was in the kitchen where she had been preparing breakfast and lunch for him to eat and take along. Their money and valuables were gone, along with a silver plated, pearl handled pistol the old man owned and carried. The old couple had used a hired man to help them with chores, whom we knew or called Ivan (John) Kiltau .

A week or so earlier, a family named Gerlach was disturbed in the night by the furious barking and actions of their big dogs, so they got up and lit a lantern and went outside, taking their dogs out too. The dogs ran over to a nearby store owned by a villager named Schleicher, with the Gerlach’s following. There they discovered two men hurrying out of a ditch dug down beside the foundation and under the store building. They had intended tunneling into the store from outside to rob the store. Mr. Gerlach had told Schleicher and several other people, that he thought he recognized Ivan Kiltau, the Bogler’s hired helper, as he crawled out from under the store. Ivan had a brother who was married and had a real shady past, whom they had figured was the other guy. When the couple was discovered dead, the people proceeded right from the fire to the residence of the brothers, where they found the pistol and a bloody hay saw. They took them both to the jailhouse, next to the courthouse. The jailer had left the day before with a prisoner going to Saratov, so they put the two brothers in separate rooms of the lockup, but had no keys to lock them in, so left a big strapping young man setting on a bench in the main room, in front of the door of the more notorious brother. He was to stay until daylight, when the courthouse opened and someone with keys might arrive, or a sotnick (constable) who could transport the brothers to Saratov for arrest and trial. It was about 6:00 a.m. so most people went back home, or to the scene, to make sure the fire embers were all out so no additional burning would occur, but Conrad and I went back to the fire and got our horses and wagon to take our flour home. The watchman had laid over on his bench and evidently fell asleep, because when he awoke he discovered that the door he had his bench in front of was standing open and the elder brother was gone. A group was formed and a search started. When they went to the house of the elder brother, his wife was there and she said he had come home and went into the loft above the kitchen, extracting items from a hiding place under the eave, which he stuck into his pockets, then left, without speaking a word to her. For several days there were supposed sightings of this man in different areas of the land around Norka, which the people later decided were false and made by friends of his, to keep everyone thinking he was still in the area so that authorities in Saratov wouldn't be alerted and start checking trains departing from there. The younger brother was taken to Saratov, where his sentence was to be deportation to Siberia, with only a two-week visit to relatives in Norka each year. I never saw the younger one after that, but thirty years later I did see the older one, who had done the crime, in Mount Clements, Michigan, where my wife and I went to a wedding of a family friend, coming from my wives village of Erlenbach. The Kiltau was senile and it was said he did silly things like pull a setting hen off her nest of eggs and he would sit on the eggs for hours, because the eggs weren't hatching fast enough. His nephew was married to our neighbor’s daughter and I never told anyone there about his deed in Norka and if they knew, they never mentioned it. He was reluctant to discuss Norka or being from there when I was introduced to him in Mount Clements.

My father used to tell us how things had changed in Norka from when he was young and living there, until when he returned, after being raised by his grandparents in Huck. Norka had many trees and swampy areas. Snakes and porcupines were things to be on the lookout for in his youth. He told how the porcupines would extend their quills and sat and waited for you to make a mistake. He told of how they would take a club and rub it gently on top of the head and neck area, making it relax, like a back rub does a person, then they clubbed it to death. When they cooked it in an old iron pot, they recovered the grease, which they used as harness oil and boot oil. The porcupines had their homes built amongst the trees in the swampy area and the youngsters would tear the mud and brush dwellings apart, then proceed with their relaxing the porcupines and clubbing them to death.

In earlier days the village of Norka and the village of Beideck, both had mills built along the Karamysch River, which separated the Beideck and Norka lands. Both mills were on the riverbank, the Beideck mill on the east shore on a little knoll and the Norka mill on the west shore on ‑flat ground. One really rough winter where there was heavy snow and during the spring rains, the area flooded and the ground around the Norka mill was undermined and the mill toppled over. The Gemeinde decided that with the private owned mills now in use in Norka, it would be foolish to go to the expense of rebuilding the old community owned mill on the river bank. Besides it was several kilometers out of the village and the local mills in town were close and sufficient. There was a man called Poste (mailman) Krieger, who carried the mail from Norka to Saratov, which brought on his nickname of Poste Krieger. He made an offer for the toppled mill, to the village councilors and they accepted, so he went to the river and disassembled the old mill and moved it back to Norka and set it up on the Ella Bahn waterway going around Norka on the south side and between the Sinner’s mill and Reicher Schleining’s mill. He too did flour and feed grinding for the area.

The most picturesque mill I ever saw, was the Giebelhaus mill out on the north of Norka in the grain lands. It ran by wind power, so they didn't grind near the amount of grain that Sinner’s mill did. The Weidenkeller family in earlier days had a windmill northeast of Norka, but it was too close to high ground around it, so it didn't get sufficient wind and it's use discontinued. Old-timers used to joke about Weidenkeller building a mill behind a hill, so they wouldn't have to work so hard.

Reicher Schleining had a mill too, but he didn't do as much grinding for the general public, because he owned the largest mercantile and feed store for miles around, so ground mostly grain which he sold as feed, or feed product for villagers, and not too much in flour quality. He had taken in my uncle to raise, when my grandparents died of cholera and he had one son of his own. He was one of the richest men in Norka, extended credit, but went to extremes to collect too, if someone didn't pay their bill. An old gent bought some hay forks from Schleining’s mercantile and didn't pay for them for some reason. In about ten years the purchaser died and Mr. Schleining went to the town council and filed a lien for the hayforks. He got the money, but some folk suggested he was a spitzboo (a sharp or unscrupulous person) for filing such a small, old claim, on the estate of a deceased. Mr. Schleining retorted that the deceased was a spitzboo for not paying his bill. Mr. Schleining owned large tracts of gardens and orchards, besides the mill, mercantile, and land, which he bought during the years buying and selling land holdings was allowed. He farmed with twelve teams of horse and oxen, using mostly hired help. He, Mr. Sinner, and Faigler the leather tanner, were probably the biggest employers of Norka. Years later, when the revolution was on and Russian troops rode into Norka to buy, or confiscate supplies, he was in an awkward position, because he owned so much and there was no way he could hide his wealth, so was subject to giving up the most. In 1918‑1919 when all of us were hiding goods, horses and anything of value, the Russian cavalry rode to the dock around Schleining’s mercantile and asked "who owns this"? He said, "I own everything you see and it's at your disposal". They loaded up wagon loads, giving him a requisition, but I don't know if he ever got any pay for it.

In about 1910, during the threshing season, when we had most of the grain stacked in mounds to thresh, a rich farmer named Albrecht, who had a hired man from the village of Messer, took it upon himself to whip the hired man for running his horses, because he was hurrying in from the fields because most of us were already there and starting to eat. Everyone sitting around eating had to see this degrading act to the hired man by an employer. The man said nothing, but ate in silence, but when the old-timers were lighting their pipes for a smoke while the food was digesting, the man slipped quietly out of sight and away. We were in the gumno (threshing area) right out of the center of the village proper. Soon we saw smoke billowing from the stacked piles of grain out in the field. It spread so fast and so hot that we couldn't fill the water wagons at the near water tanks, but had to go to the next tanks and around throuqh the fields to get it from the back to control its spread. The creek would hold it from getting into the village, but the piled grain in six threshing areas was completely burned before it was controlled. The men decided that the hired man from Messer had slipped out to the edge where the furthest piles were and set them on fire with his pipe lighting punk and flint, then headed away toward Saratov in a gullied area. They sent riders on the roads watching for him and intended to bring him back and throw him into the fire for his crime. Reverend Staerkel came out and supposedly walked around the fire praying, which caused it to cease, but in reality the hot fire was the piles of stacked grain, but around it was stubble fields where the grain had been cut and hauled away from. This is where the Reverend Staerkel walked and where the villagers hauled wagons of water into which we wet blankets and such, which we dragged over the creeping fire in the stubble. I later heard that the hired man had taken refuge in the village of Mohr (Moor).

In 1912, my brother George and his wife Louisa Schnell Brill, sent home two fares from Portland, Oregon, for me and my sister Lena to come join them and our sister Elizabeth Schleining and her husband Jacob. I had just discovered girls, so used the excuse that I didn't want to leave our parents, so didn't want to go. My brother Conrad, eight years older than I, had been going with a Urbach girl in Norka, whose family sent her and her brother over here earlier, with relatives going to Portland, so my brother Conrad decided he would come in my place. They left Norka and got to Oregon and he then married his old girlfriend and my sister Lena met and married John Leichner in Ritzville, Washington, later moving to Portland too. A real problem in Russia concerned the fact that our German people wouldn't integrate with the Russian population. Instead they intermarried with cousins, so consequently you could hardly find a Russian living amongst us in most villages. We had good land, until we and the Russians, who started villages around us, got over populated. Then when peasants in town got upset with their government, the villagers around us got upset with us and our land holdings. Many a Russian peasant was whipped for gathering firewood on a Germans property, even for branches that the wind blew down. Most Russian peasants had a little goat, which they milked for their children’s milk, and some were beaten because they let their goat over into the Germans field to fill it's belly. Rich Germans hired Cossacks as patrolmen if their land bordered Russian land. These Cossacks were hard on the Russian peasants, as they had been on the earliest German immigrants when they arrived from Germany and the Cossacks traveled in bands, making raids on the cattle and horses of our earliest settlers.