The Fate of a Schreiber Family

Written by Alexander Schreiber

My great grandfather Johann Georg Schreiber and great-grandmother Catharina Elisabeth Schreiber (née Schleicher) had nine children, including three sons who lived to be adults: Georg, Peter, and Conrad.

In 1907, the oldest son Georg and his family immigrated to the United States and settled in the State of Washington.

Peter and his family arrived in Quebec, Canada in September 1913 and soon settled in the Volga German community in Portland, Oregon.

The elder brothers (Georg and Peter) urged my great-grandmother to go with them to the USA, but she decided to stay with her younger son, Conrad. She was a widow at this time as my great-grandfather died in Norka in 1893.

In 1907, the oldest son Georg and his family immigrated to the United States and settled in the State of Washington.

Peter and his family arrived in Quebec, Canada in September 1913 and soon settled in the Volga German community in Portland, Oregon.

The elder brothers (Georg and Peter) urged my great-grandmother to go with them to the USA, but she decided to stay with her younger son, Conrad. She was a widow at this time as my great-grandfather died in Norka in 1893.

My grandfather, Conrad Schreiber, was born in the German settlement of Norka in Saratov Province in 1888 and he decided to stay in Russia. In 1918, grandfather Conrad married Nina Heinz (born in 1897), a daughter of the merchant Heinrich Heinz from Pokrovsk (now the city of Engels, Russia).

This photo of the author's family was taken between the years 1921-1922 in Norka, Russia.

From left to right: Great-grandmother Catharina Elisabeth Schreiber (born Schleicher on December 16, 1847 in Norka); Great-grandfather, Heinrich Heinz; Grandmother, Nina Schreiber (née Heinz, born 1897); Grandfather Conrad Georg Schreiber (born August 3, 1888 in Norka); Father, Alexander Konrad Schreiber (born June 7, 1919 in Norka).

In the second row, between Great-grandfather Heinrich Heinz and Grandmother Nina Schreiber, is Catharina Maria Schreiber (born May 11, 1886) the sister of Conrad Georg Schreiber. Catherina Maria Schreiber died at a young age, somewhere at the end of 1920’s. She lived her last years in Saratov or in Engels. Standing between Nina and Conrad Georg Schreiber is Bertha Schreiber. Berta died in Germany in 2003. - Source: Alexander Schreiber

Grandfather Conrad had a large house and garden in Norka (Sadovaya Street #20). Grandfather worked in the blacksmith shop which was built next to the house. At that time, blacksmiths were respected people in the villages, and more over, they earned a good living. Grandfather's family was prosperous.

In 1918, there was a rebellion against the Soviet rule in Norka. A detachment of the rebels attacked the nearest railway station at Talovka (German name: Beideck; Current name: Luganskoe), where a Red partisan detachment was situated. Later, during an interrogation, grandfather confessed that he had taken part in the rebellion and in the attack of Talovka. Despite the fact that examination records were falsified in 1937, it appears as if grandfather really participated in the rebellion. According to some records, he made cold steel for the rebels in his forge. Despite his involvement, his role in the rebellion was not the most important, demonstrated by the fact that the Bolsheviks took no action against him for almost 20 years.

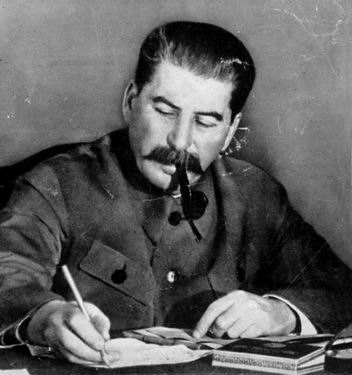

In June 1919, the first child appeared in grandfather's family - my father Alexander Konrad Schreiber. The famine of the 1920s did not spare grandfather's family and their second child died at a very young age. In the 1920’s and 1930’s, famine visited the Volga region many times. My father told me that there had been some cases of cannibalism in the region. We could not wait for help from anywhere. Until the end of the 1920’s, my grandfather corresponded with his brothers in the USA who had sent money orders to Russia to help the family. Later, Stalin forbid correspondence outside of Russia and the family relations broke down (it was only in 2004 that I found the offspring of the Schreiber brothers in the USA).

In June 1919, the first child appeared in grandfather's family - my father Alexander Konrad Schreiber. The famine of the 1920s did not spare grandfather's family and their second child died at a very young age. In the 1920’s and 1930’s, famine visited the Volga region many times. My father told me that there had been some cases of cannibalism in the region. We could not wait for help from anywhere. Until the end of the 1920’s, my grandfather corresponded with his brothers in the USA who had sent money orders to Russia to help the family. Later, Stalin forbid correspondence outside of Russia and the family relations broke down (it was only in 2004 that I found the offspring of the Schreiber brothers in the USA).

In 1925, a daughter Emma was born in grandfather's family. In 1927, my father began his first grade studies in Norka. In 1929, daughter Ida was born; in 1932 a daughter Minna was born. In 1934, my father finished the 7th grade. At that time in Russia, there were 7-year and 10-year schools. In Norka there was no 10-year school. Those who wanted and could afford to continue their education had to leave home. By 1934, the family of my grandfather grew poor. Grandmother did not work because she was bringing up four children. Grandfather did not have the financial opportunity to send my father to study further. My father began working as a registrar at a machinery-tractor station (MTS).

In May 1937, a son Friedrich (Fyodor) was born. In 1937, a 10-year school was opened in Norka, and on the 1st of September my father began the 8th grade.

On December 18, 1937, a representative of the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (PCIA) from Balzer colony (a large German colony near Norka; now Krasnoarmeysk), by the name of F. F. Bauer came in the house of my grandfather together with a witness I. I. Moor (Mohr). Grandfather was searched and an arrest warrant (number 1104) was issued by the PCIA ASSRWD (the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of the Wolga Deutschen). They confiscated a gun, a self-made knife, and took grandfather away. No relative ever saw him again. Nobody knew why he was arrested. After many days passed, there was no news of grandfather. My father repeatedly tried to find out what had happened with grandfather. Father was told that if he continued to ask about grandfather, they would arrest him too. Only in 1989 did we find out about grandfather's fate. In 2004, in the basement of Lubyanka (KGB Headquarters) in Moscow, I read grandfather's criminal case and learned of his last days. Until 1989 we hoped that grandfather was still alive in one of Stalin's camps. Maybe he had another family by this time. When I worked in Siberia, I hoped to meet people who had known my grandfather after 1937.

In May 1937, a son Friedrich (Fyodor) was born. In 1937, a 10-year school was opened in Norka, and on the 1st of September my father began the 8th grade.

On December 18, 1937, a representative of the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (PCIA) from Balzer colony (a large German colony near Norka; now Krasnoarmeysk), by the name of F. F. Bauer came in the house of my grandfather together with a witness I. I. Moor (Mohr). Grandfather was searched and an arrest warrant (number 1104) was issued by the PCIA ASSRWD (the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of the Wolga Deutschen). They confiscated a gun, a self-made knife, and took grandfather away. No relative ever saw him again. Nobody knew why he was arrested. After many days passed, there was no news of grandfather. My father repeatedly tried to find out what had happened with grandfather. Father was told that if he continued to ask about grandfather, they would arrest him too. Only in 1989 did we find out about grandfather's fate. In 2004, in the basement of Lubyanka (KGB Headquarters) in Moscow, I read grandfather's criminal case and learned of his last days. Until 1989 we hoped that grandfather was still alive in one of Stalin's camps. Maybe he had another family by this time. When I worked in Siberia, I hoped to meet people who had known my grandfather after 1937.

On December 18, 1937 grandfather was taken to Balzer. On the 20th of December, he was interrogated in a small room by the Balzer militia. They reminded him of his participation in the rebellion of 1918, and also accused him of threatening a former Red communist partisan and inhabitant of Norka, A. I. Sterkel, in May and December of 1937. Another inhabitant of Norka, B. I. Adam, confirmed that he had heard grandfather's threats. Grandfather confessed his participation in the rebellion, but he quickly rejected the accusations of threats to Sterkel, the former Red Soviet partisan.

The year 1937, the most terrible year of Stalins terror, was coming to an end. The PCIA was sending plans from Moscow about how many people were to be arrested in every province, region, and village. In December they remembered my grandfather. The testimony of fellow villagers was created by the PCIA officials themselves. As well as grandfather's reference of December 18, 1937 issued by Norka's village counsel. They also reminded him of the fact that at the beginning of the 1930’s he had not joined a collective farm, but continued to work as an individual holder. An excerpt from the interrogation document states that he: "was an active participant of a counter-revolutionary White band in 1918. Schreiber, being a blacksmith, made weapons for the bandits. He agitated against all the measures of the Soviet rule and did not want to join the collective farm. He is engaged in counter-revolutionary Fascist activities." The direction of the Balzer PCIA was to draw up an indictment. Case number 2835 stated: “the charges against the former bandit Schreiber Conrad Egorovich (Conrad, son of Georg), are to be submitted for consideration of the three-man commission of the PCIA ASSRWD.” Grandfather was interrogated and the indictment was signed up by the assistant of the executive plenipotentiary of the State Security Administration of the PCIA Balzer Cantonal department (CD), Mr. Mattern. The indictment was also signed up by the director of the Balzer Cantonal department of the PCIA ASSRWD junior lieutenant of the State Security, Mr. Khmelev, and by the director of the 4th department of the PCIA ASSRPG lieutenant of the State Security, Mr. Davtyanz. On the basis of article 18 of the Law of Russia titled, "About Rehabilitation of the Political Repressions' Victims" which was effective October 18, 1991, all the people associated with the arrest of grandfather should be criminally responsible for their activities, but all of them, and many other PCIA officials, have escaped without any penalty.

Grandfather was moved to Engels and incarcerated. On the 22nd of December, the three-man commission of the PCIA ASSRWD made their ruling. Grandfather was accused of “terrorist intentions towards a member of the ARCPB (the All-Russian Communist Party of Bolsheviks) and attempts to assault a member of the Red Army.” They resolved to execute Conrad Egorovich Schreiber by shooting. Grandfather was shot on the 27th of December at 11 p.m. in Engels. As I was informed by the Saratov region's FCB: “To determine the place of your granddad's burial is impossible because of the rules existed at that time.” In 1989, when the State Security Committee (SSC) of the USSR first informed my father of grandfather's shooting, SSC did not know either the town of execution, or the time of it. Perhaps time will pass, and I will find out where my grandfather's grave is situated. The PCIA, SSC and FCB keep all the dossiers of those they killed. For 67 years the dossier of my grandfather was kept. For 63 years the dossier of my father is being kept in the city of Perm. Everything has been kept. I am certain that the dossiers of hundreds of thousands of the communist regime's victims have been kept. But until civil people are allowed in the archives of FCB in order to count the number of these victims, Russia and the whole world will not know how many people were repressed in those years.

The year 1937, the most terrible year of Stalins terror, was coming to an end. The PCIA was sending plans from Moscow about how many people were to be arrested in every province, region, and village. In December they remembered my grandfather. The testimony of fellow villagers was created by the PCIA officials themselves. As well as grandfather's reference of December 18, 1937 issued by Norka's village counsel. They also reminded him of the fact that at the beginning of the 1930’s he had not joined a collective farm, but continued to work as an individual holder. An excerpt from the interrogation document states that he: "was an active participant of a counter-revolutionary White band in 1918. Schreiber, being a blacksmith, made weapons for the bandits. He agitated against all the measures of the Soviet rule and did not want to join the collective farm. He is engaged in counter-revolutionary Fascist activities." The direction of the Balzer PCIA was to draw up an indictment. Case number 2835 stated: “the charges against the former bandit Schreiber Conrad Egorovich (Conrad, son of Georg), are to be submitted for consideration of the three-man commission of the PCIA ASSRWD.” Grandfather was interrogated and the indictment was signed up by the assistant of the executive plenipotentiary of the State Security Administration of the PCIA Balzer Cantonal department (CD), Mr. Mattern. The indictment was also signed up by the director of the Balzer Cantonal department of the PCIA ASSRWD junior lieutenant of the State Security, Mr. Khmelev, and by the director of the 4th department of the PCIA ASSRPG lieutenant of the State Security, Mr. Davtyanz. On the basis of article 18 of the Law of Russia titled, "About Rehabilitation of the Political Repressions' Victims" which was effective October 18, 1991, all the people associated with the arrest of grandfather should be criminally responsible for their activities, but all of them, and many other PCIA officials, have escaped without any penalty.

Grandfather was moved to Engels and incarcerated. On the 22nd of December, the three-man commission of the PCIA ASSRWD made their ruling. Grandfather was accused of “terrorist intentions towards a member of the ARCPB (the All-Russian Communist Party of Bolsheviks) and attempts to assault a member of the Red Army.” They resolved to execute Conrad Egorovich Schreiber by shooting. Grandfather was shot on the 27th of December at 11 p.m. in Engels. As I was informed by the Saratov region's FCB: “To determine the place of your granddad's burial is impossible because of the rules existed at that time.” In 1989, when the State Security Committee (SSC) of the USSR first informed my father of grandfather's shooting, SSC did not know either the town of execution, or the time of it. Perhaps time will pass, and I will find out where my grandfather's grave is situated. The PCIA, SSC and FCB keep all the dossiers of those they killed. For 67 years the dossier of my grandfather was kept. For 63 years the dossier of my father is being kept in the city of Perm. Everything has been kept. I am certain that the dossiers of hundreds of thousands of the communist regime's victims have been kept. But until civil people are allowed in the archives of FCB in order to count the number of these victims, Russia and the whole world will not know how many people were repressed in those years.

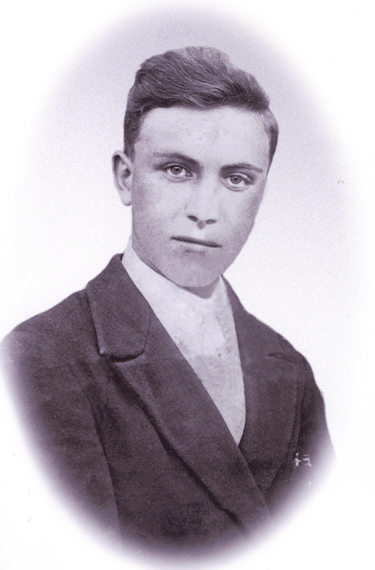

In 1938, my father finished the 8th grade. But he could not continue education, because he had to maintain the family: his mother, younger brother, and sisters. Father started working as a registrar at a textile factory in Norka, and then he became an assistant to the chief accountant. Father was a very handsome young man and physically strong. He played almost all the musical instruments (except violin and piano): bayan, concertino, guitar, mandolin, and brass. But best of all, he played the trumpet. Later in life when he was living in Kazakhstan, father played in a brass band of a state farm. Their band took first prizes in Kustanay region.

In 1941, the war with the fascist Germany began. On August 28, 1941 the well known decree of the USSR Supreme Soviet's Presidium titled “Resettlement of the Volga Germans" was released. On September 7, 1941, the decree titled "Administrative Structure of the Territory of the Former Republic of Volga Germans" was given. In a short time, the Volga German Autonomous Republic was liquidated. According to the January 17, 1939 census, 366,865 ethnic Germans lived in the Republic of the Volga Germans. In August 1941, the Order of the PCIA USSR was released with a top secret stamp: “Measures for Implementation of the Operation of the German Resettlement from the Volga German Republic, Saratov, and Stalingrad Regions”. The Order said specifically:

In 1941, the war with the fascist Germany began. On August 28, 1941 the well known decree of the USSR Supreme Soviet's Presidium titled “Resettlement of the Volga Germans" was released. On September 7, 1941, the decree titled "Administrative Structure of the Territory of the Former Republic of Volga Germans" was given. In a short time, the Volga German Autonomous Republic was liquidated. According to the January 17, 1939 census, 366,865 ethnic Germans lived in the Republic of the Volga Germans. In August 1941, the Order of the PCIA USSR was released with a top secret stamp: “Measures for Implementation of the Operation of the German Resettlement from the Volga German Republic, Saratov, and Stalingrad Regions”. The Order said specifically:

“To dispatch to the place an operations group of the PCIA USSR at the head of the deputy of the people's commissar of the USSR Internal Affairs Serov; to lay responsibility for the preparation and putting into effect of the operation on the operation groups, consisting in the Republic of Volga Germans of: the head and senior major of the State Security, comrade Nassedkin; people's commissar of the Internal Affairs of the Republic of Volga Germans and major of the State Security, comrade Gubin; the head of the SPU department, captain of the State Security comrade Iljin; and the head of the department of transport management, captain of the State Security, comrade Potapov.

“Responsible people are to organize three-man commissions for putting the operation into effect that should be realized from the 1st to the 20th of September 1941 according to the enclosed instructions.”

“To dispatch into the Republic of the Volga Germans for putting the operation into effect: 1,200 PCIA officials, 2,000 militia officials, 7,350 Red Army men at the head of the brigade commander Krivenko.”

Signature: L. Beria

Lavrenti Beria: Chief of the notorious NKVD, the Soviet secret police. Stalin quickly brought Beria up through the ranks of the Communist party, and selected him to head the NKVD in 1938. Stalin used Beria to stage his purges. Under Beria, the NKVD was responsible for the deaths of millions of Russians. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

All the German population of Norka was to be evicted within days. Sometimes exceptions were made for women whose husbands were ethnic Russians or other non-German group. The people were forced to leave their houses and all their property. Only certain items could be hand carried with them. The whole family of my father was evicted. The people went on foot to the nearest railway station where they were loaded into wagons built for hauling goods. The husband of my aunt Emma Schreiber, Conrad Urbach (born in Norka, but deported from Balzer), remembers: “We were going on foot to the Uvek wharf on Volga, and then we were taken by barge to Saratov. In Saratov we were loaded into wagons. It took us a long time to reach the Zhangiztobe railway station in Semipalatinsk region of Kazakhstan through Middle Asia.” Other groups of people from Norka were taken further into Siberia. At the station Kulunda in Altai region they were unloaded. They were settled in the village Zav'yalovo of Altai region (210 km into the West from city Barnaul). Father asked the Zav'yalovo area military committee to send him to the battle-front, but they refused. At that time, very few people in the local Russian population wanted to go to the front. Father began working as an accountant at a local collective farm.

On January 10, 1942 the Decree of the State Committee of Defense titled “Order to Use the Germans Settlers of Call-Up Age from 17 to 50 Years Old” (issued with a 'top secret' stamp) stated:

On January 10, 1942 the Decree of the State Committee of Defense titled “Order to Use the Germans Settlers of Call-Up Age from 17 to 50 Years Old” (issued with a 'top secret' stamp) stated:

“With a view to use the masculine Germans-settlers from the age of 17 to 50 years old efficiently:

1. To mobilize all the German men from the ages of 17 to 50 years old, fit for physical labor, evicted in Novosibirsk and Omsk regions, Krasnoyarsk and Altai regions, and Kazakhstan SSR, in number of 120 thousand in the work columns for a war time, and to transfer 45,000 men out of this number to PCIA USSR for timber procurement. To start the mobilization forthwith and finish it on the 30th of January 1942.

2. To oblige all the mobilized Germans to appear at assembly points of People's Commissariat of Defense in good winter clothes with supply of linen, bed-clothes, a mug, a spoon, and 10-day supply of food.

3. To oblige People's Commissariat of Communications to provide transportation of the mobilized Germans during January with delivery to the place of work till the 10th of February.

4. To oblige PCIA USSR to prescribe precise order and discipline in the work columns and detachments of the mobilized Germans, providing high labor productivity and fulfillment of output programs.

5. To charge PCIA USSR with the cases regarding those mobilized Germans who will not appear in recruiting centers and at assembly points for dispatch, and also regarding those in the work columns who will break discipline and refuse to work, who will not appear at mobilization, desert from the work columns; to examine these cases at Special Meeting of PCIA USSR with use of the death penalty to the most malicious ones.

6. To prescribe norms of food and manufactured goods provision for the mobilized Germans according to the norms, prescribed to the GULAG by the PCIA USSR.

Signature: J. Stalin

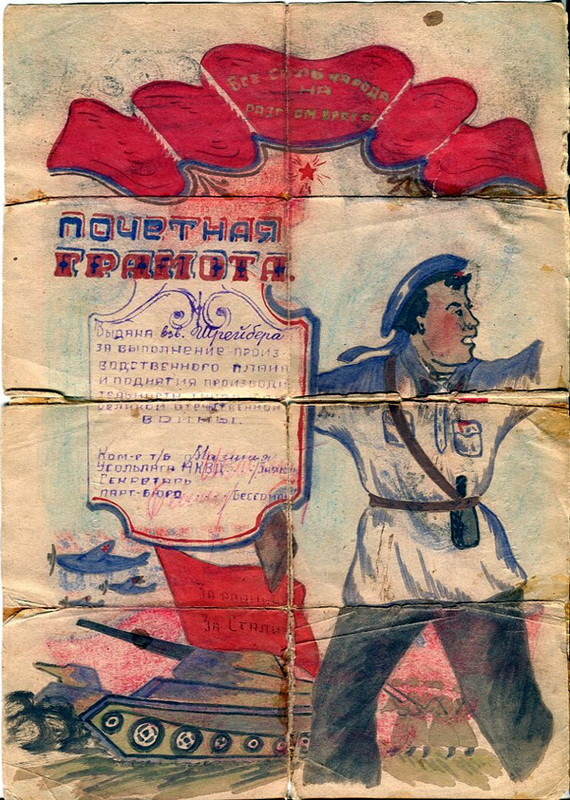

On January 15, 1942, my father was mobilized by the Zav'yalovo military committee. On February 15, 1942, he arrived in Usollag (part of the GULAG system) which was located in the Cherdyn area of the Perm region in the Northern Urals, near the town of Solikamsk. Already on January 12, 1942 there was a detachment of the mobilized Germans in Usollag according to the Order 0083 of PCIA USSR. The Cherdyn and Nurob areas, where my father spent many years, are the most northern areas of Perm region. Even now those are wild places that are the source of the rivers Kama, Vishera, Kolva, dense forests, mountains, rare and sparsely populated villages. In 1965, I visited those places. Many villages did not have electricity even then. Father was taken to a work camp named Mazunya. On the 1st of January 1942, there were 37,111 men (living prisoners) in the camp. We can only guess how many of them died. The guards treated the mobilized Germans as fascists. On the entrance road leading to the forest camp, my father saw long rows of graves with crosses. "You all will lay there" the guards assured them. My father, as I already said, was physically very strong, taller than average and had experience working as a registrar and accountant. He was also appointed as foreman of a platoon of woodcutter's under the camps semi-military structure (group, platoon).

A hand made certificate of honor that was presented to Alexander Schreiber's platoon at Usollag for the successful implementation of a production plan that increased labor productivity during the Great Patriotic War (Russian term for World War II). The certificate is signed by the Usollag camp Commander and People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, Zaikin (it is illegible) and Secretary of the Communist Party Bureau, Bessonov. In the top part of the certificate's banner is the motto: "All forces of the people for the defeat of the enemy". In the lower part of the certificate on the red banner above the tank is written: "For the Homeland! For Stalin!". The certificate was made on a dense sheet of paper and illustrated with paints and colored pencils. This document is provided courtesy of Alexander Schreiber (Moscow).

On October 7, 1942, the Decree of the State Defense Committee (SDC) “About Additional Mobilization of the Germans for the National Economy of the USSR” was issued with a top secret stamp. The SDC resolved:

1. To mobilize in work columns all the German men from the ages of 15 to 16 and 51 to 55 years old (inclusive), fit for physical labor, for the whole period of war.

2. To mobilize in work columns also the German women from the ages of 16 to 45 years old (inclusive) for the whole period of war. To exempt from the mobilization pregnant German women and those, having children under 3 years old.

3. The children over 3 years old will be passed for upbringing to other members of a family. In the absence of other members of a family, except the mobilized, children are passed for upbringing to the nearest relations or collective farms. To oblige the local unions to take measures for placing the children of the mobilized Germans who no longer have parents.

4. To start mobilization of the Germans forthwith and finish it during the month.

My paternal grandmother, Nina Schreiber (née Heinz) was 45 years old in August 1942, Emma was 17, Ida was 13, Minna was 10 and Fyodor was 5 years old. My grandmother was ill, but father’s sister Emma was mobilized and taken away to Chelyabinsk. Emma worked at building the Chelyabinsk Metal Works. In those years about 70,000 mobilized Russian Germans worked at the plants and mines of Chelyabinsk.

My grandmother, along with two little daughters and the child Fyodor stayed in Zav'yalovo alone.

Father cut trees in the northern work camp and was later appointed as head of the food store. Father managed to hide that grandfather Conrad had been arrested in 1937. In family profiles father wrote that grandfather had died before the war. If the camp authorities found out that father was a son of the ‘people's enemy’, ‘a white bandit', he would have had a much harder time. In January of 1945, a new work camp was founded: “Nyroblag”, which included the sector where my father worked. In one of the villages in the camp area (Novina), my mother, Claudia Vilesova, worked a school teacher. She is Russian. She had a hard time with her parents, when they learned that she loved a “fascist.” Her parents became acquainted with my father in 1945. By the end of war they began regarding the Germans in a friendlier manner. Father was allowed to live in the territory of the village. In 1946, the first child was born to my parents - Alexander. Unfortunately, the baby died at a very young age. In October 1947, in Novina, my elder brother Vladimir was born. In 1948, three years had passed from the end of war, but the status of the Germans did not change, though they had been “mobilized” only for duration of the war. All of them were waiting for release from the camps. At last, on November 26, 1948 a top secret decree of the Supreme Soviet Presidium of the USSR was issued. All the Germans in the work camps, including my father, had to give a written confirmation that they had been informed about this decree. The “Decree About Criminal Responsibility for Escape from the Places of Obligatory and Permanent Settlement of the People, Evicted in the Remote Regions of the Soviet Union in the Period of the Patriotic War” said in particular:

My grandmother, along with two little daughters and the child Fyodor stayed in Zav'yalovo alone.

Father cut trees in the northern work camp and was later appointed as head of the food store. Father managed to hide that grandfather Conrad had been arrested in 1937. In family profiles father wrote that grandfather had died before the war. If the camp authorities found out that father was a son of the ‘people's enemy’, ‘a white bandit', he would have had a much harder time. In January of 1945, a new work camp was founded: “Nyroblag”, which included the sector where my father worked. In one of the villages in the camp area (Novina), my mother, Claudia Vilesova, worked a school teacher. She is Russian. She had a hard time with her parents, when they learned that she loved a “fascist.” Her parents became acquainted with my father in 1945. By the end of war they began regarding the Germans in a friendlier manner. Father was allowed to live in the territory of the village. In 1946, the first child was born to my parents - Alexander. Unfortunately, the baby died at a very young age. In October 1947, in Novina, my elder brother Vladimir was born. In 1948, three years had passed from the end of war, but the status of the Germans did not change, though they had been “mobilized” only for duration of the war. All of them were waiting for release from the camps. At last, on November 26, 1948 a top secret decree of the Supreme Soviet Presidium of the USSR was issued. All the Germans in the work camps, including my father, had to give a written confirmation that they had been informed about this decree. The “Decree About Criminal Responsibility for Escape from the Places of Obligatory and Permanent Settlement of the People, Evicted in the Remote Regions of the Soviet Union in the Period of the Patriotic War” said in particular:

“With regard to the settlement of the evicted Chechens, Karachaevetzs, Ingushes, Balkaretzs, Kalmyks, Germans, Crimean Tartars, etc. by the Supreme Organ of the USSR in the period of the Patriotic War and also in connection with the fact that at the time of their resettlement the time limits of their eviction were not determined, to establish that the resettlement of the above mentioned people in the remote regions of the Soviet Union was implemented in perpetuity, without right for return in the places of their previous residence. Evicted persons, guilty of self-willed escape from the places of obligatory settlement, are criminally responsible. The penalty for such a crime is 20 years of penal servitude.”

In this early 1950's photograph, Alexander Konrad Schreiber is shown seated on the right. Alexander's wife, Claudia is seated in the center and a friend of Alexander's from Norka, Egor Schlidt, is seated to the left. At this time, life in the camps began to be ease in comparison with the terrible years at the beginning of war. Courtesy of Alexander Schreiber.

Camp regime was cancelled for my father, but an everlasting exile began. Father corresponded with his mother. He persuaded her to move with him in the Urals with the younger sisters and brother. Together they would overcome the difficulties more easily. Grandmother was allowed to move which she did in the autumn of 1948. In Zav'yalovo, grandmother was engaged in market-gardening, in order to feed the children. In the summer, they worked on their small potato plot outside of the village. They planned to sell their entire crop in autumn in order to gather more money for the move. On the 7th of July, the whole family was going home from the potato field when suddenly a strong thunderstorm broke out. Ida was frightened and ran from the rain to seek shelter under the trees. After running a short distance, she was struck by lightning. By the time her family reached her, Ida was already dead. She was 18 at the time and is buried in Zav'yalovo.

In autumn, grandmother with her two children, Nina and Fyodor, started out on the long journey. They went through Chelyabinsk. There they managed to meet Emma after 6 years of separation. At last they reached Novina, where my father lived. In the neighboring village, father set up mother and the children in a separate house. On April 7, 1949, father was given permission to settle in the village Novina forever. Father started working an accountant at the collective farm.

In the village there were a lot of exiles from the Western Ukraine who were relatives of the activist Ostap Bandera who had led a nationalistic movement. They were mostly elderly people and children. They were cultured people who very much respected my father's family and always addressed them with esteem: “Pan accountant.” “Pani teacher.” Father enjoyed the respect of the whole village.

One afternoon a truck stopped by a shop in the village. In the truck were big metal barrels filled with petrol. The driver entered the shop. In that moment one of the barrels began burning. Soon the rest of the barrels began burning. The flames engulfed the whole body of the truck. People, including the driver, ran away from the shop. My father was passing by the shop at this time and without hesitation jumped into the bed of the truck, opened the side enclosures, and began throwing the barrels down onto the ground barehanded. As the barrels rolled on the ground, the flames went out. Father threw down all the burning barrels, thereby preventing an explosion. All the skin on one of his hands was burned.

In autumn, grandmother with her two children, Nina and Fyodor, started out on the long journey. They went through Chelyabinsk. There they managed to meet Emma after 6 years of separation. At last they reached Novina, where my father lived. In the neighboring village, father set up mother and the children in a separate house. On April 7, 1949, father was given permission to settle in the village Novina forever. Father started working an accountant at the collective farm.

In the village there were a lot of exiles from the Western Ukraine who were relatives of the activist Ostap Bandera who had led a nationalistic movement. They were mostly elderly people and children. They were cultured people who very much respected my father's family and always addressed them with esteem: “Pan accountant.” “Pani teacher.” Father enjoyed the respect of the whole village.

One afternoon a truck stopped by a shop in the village. In the truck were big metal barrels filled with petrol. The driver entered the shop. In that moment one of the barrels began burning. Soon the rest of the barrels began burning. The flames engulfed the whole body of the truck. People, including the driver, ran away from the shop. My father was passing by the shop at this time and without hesitation jumped into the bed of the truck, opened the side enclosures, and began throwing the barrels down onto the ground barehanded. As the barrels rolled on the ground, the flames went out. Father threw down all the burning barrels, thereby preventing an explosion. All the skin on one of his hands was burned.

In April 1950, my brother Victor was born. In April 1952, my sister Galina was born. In May 1954, the commandant's office of the city Cherdyn allowed my father and grandmother to go to Chelyabinsk for their holiday. My father spent ten days in Chelyabinsk and for the first time in 12 years visited his sister Emma. In the commandant's office of Chelyabinsk they made notes of my father's arrival and departure. Aunt Emma lived in a workers' barrack. She was already married to Conrad Urbach, native of Norka. They had three children: Volodya, Irina, and Lida.

In September of 1954, my sister Ida was born. To the end of 1954 father had already a big family: a wife and four children. My mother's mother, Alexandra Vilesova, lived with them too. By that time my mother's relatives already loved and respected my father. He was a sociable man. In the Russian villages people drank a lot of home made vodka. Life was hard and people wanted to abstract themselves from it in this way. But my father never got drunk, independent of how much he drank. Such good health he had. Granny Alexandra used to say: “Sasha, will I see you drunk one day at last?” However, she never saw him intoxicated for 45 years.

In September of 1954, my sister Ida was born. To the end of 1954 father had already a big family: a wife and four children. My mother's mother, Alexandra Vilesova, lived with them too. By that time my mother's relatives already loved and respected my father. He was a sociable man. In the Russian villages people drank a lot of home made vodka. Life was hard and people wanted to abstract themselves from it in this way. But my father never got drunk, independent of how much he drank. Such good health he had. Granny Alexandra used to say: “Sasha, will I see you drunk one day at last?” However, she never saw him intoxicated for 45 years.

On December 13, 1955, the Decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet: “About Removal of the Restrictions in the Rights of the Germans and Members of their Families, Who Are Now in the Special Settlements” was issued. The decree said:

“Taking into consideration that the existing restrictions in the rights of the Germans and members of their families, evicted in different regions of the country, are not necessary any more:

1. To strike off the register of special settlement and release the Germans and members of their families, evicted into special settlements during the Great Patriotic War, from the administrative surveillance of the Ministry of Internal Affairs' organs.

2. To establish that the removal of the restrictions of special settlement does not involve the restitution of property, confiscated by eviction, and they do not have the right to return in the places they have been evicted from."

On January 28, 1956, my father signed a receipt in the commandant's office that he understood this decree. On February 14, 1956, the criminal case for evicted German Alexander Conradtjevich Schreiber was closed by the Cherdynsk commandant's office. But before this event, a tragedy happened in father's family. On the 10th of January, grandmother Nina went alone from her house into father's village. She had been frequently ill at this time and on the journey she quickly tired. She sat down by a tree to have some rest, fell asleep, and froze to death. She was buried in Novina. By that time aunt Nina was already married to a Russian man. She had children and the younger brother of my father, Fyodor, stayed with her. Father was free. He could go away from the forest wilderness, but nobody knew where.

It was impossible to keep living in the same place. In general there were only two types of men around: camp prisoners and their guards. My brothers were getting older, and at outdoor parties drunken men asked them: Who do you want to be in the future, guards or prisoners?" And my brothers answered: “Prisoners.” Evidently my brothers thought the prisoners were more humane people.

Father decided to move to Chelyabinsk, closer to his sister Emma. Chelyabinsk was already a large city at that time and a job could be easily found. In 1956, father, mother, their four children, and granny Alexandra moved to Chelyabinsk. My father's exile friend and a native of Norka, Egor Schlidt (Georg Schlidt), returned to Zav'yalovo where he had left his family.

The family did not live in Chelyabinsk for long. They found jobs, but habitation was a big problem. At that time, beginning in 1954, the neighboring region of Kazakhstan was developing virgin lands and expanding greatly. Wild steppe was being ploughed up for grain-crops. New settlements were being built. Father decided to go to the virgin lands. They moved 300 km southeast from Chelyabinsk, in the Kostanay region of Kazakhstan. The family started living at the central farmstead of a new State farm named “Korzhunkolskiy.” The place was beautiful: woods and steppes, a wide clearing where a settlement began to be built. Around the farm there were birch and aspen woods and huge fields. That State farm was founded by volunteers from Moscow and Ukraine. There were a few German families who got there by different circumstances. There were only two or three Kazakh families out of several thousand people. In general, there were only a small number of Kazakh nationals in the Northern and Central parts of Kostanay region. Father bought an earth-house, and in a year he built a new house nearby. My father's sister, Nina, with her family later moved to us on the State farm. Uncle Fyodor stayed in Chelyabinsk with his sister Emma.

In 1959, Fyodor was called out for three years in the Soviet Army. In February 1959 I was born. Father was a master in a construction shop of the State farm; mother was a teacher in elementary school. My parents were respected in the village. Mother taught hundreds of children over these years. Father was elected a head of workers' trade union of the State farm in 1966. At that time, people were designated for such posts only by recommendation of the authorities, but they suggested honest and respectable people. My father as elected as a deserving candidate. He was not nominated for a second term, because it was very difficult to fight against the administration for workers' rights, and the authorities assigned him another job to remove him from the leadership of the trade union.

In 1962, Fyodor Schreiber returned from the Army. The same year he was married to a Russian woman in Chelyabinsk. Mother and father went to Chelyabinsk for the wedding and also took me there. In 1963, the first child was born in Fyodor's family - Vladimir Schreiber.

In 1965, my brother Victor finished the 8th grade and left home at the age of 15 years old. He started studying at a radio engineering college in the city of Sverdlovsk (now named Yekaterinburg).

In 1966, I began first grade. My first teacher was my mother. My parents were very modest, honest people. I was a talented boy. I read freely at age 5. I went to the village library by myself to check out books. Friends advised my parents to send me to school earlier. But they decided that they should be modest and I went to school together with my contemporaries at the age of seven years old. In autumn 1966, my elder brother Vladimir was called out into the Army. He served two and one-half years in the rocket forces, on the space-vehicle launching site Baikonur, as we learned later. In 1969, my brother Victor got married to a student from his group. In the same year, Victor’s first son, Aleksey Schreiber, was born.

In 1970, my brother Volodya got married too. He made his wife's town, Rudniy, his home. Rudniy was 50 km from our village. Volodya worked in geological expedition, studied in the Moscow Polytechnic Institute - Department of Mines. In 1971, my sister Galina got married. She moved to her husband’s family in another village. My sister Ida and I stayed together with our parents.

In 1971, a new town Lisakovsk began to be built 120 km from us. A layer of ironstone was found there and a big open-cast mine began to be dug. Small settlements were pulled down. Settlement Stepnoy was pulled down too. A lot of Germans lived there and part of this group was resettled in our village. A Nagel family moved here too. Their father was a native of Norka. I do not remember now how he got to Stepnoy. His sons, Iakov and Adam were my classmates.

On November 3, 1972 the Decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet: “Regarding Removal of the Restrictions in the Choice of Place of Residence, Provided in the Past for Some Categories of Citizens” was issued. The decree said:

It was impossible to keep living in the same place. In general there were only two types of men around: camp prisoners and their guards. My brothers were getting older, and at outdoor parties drunken men asked them: Who do you want to be in the future, guards or prisoners?" And my brothers answered: “Prisoners.” Evidently my brothers thought the prisoners were more humane people.

Father decided to move to Chelyabinsk, closer to his sister Emma. Chelyabinsk was already a large city at that time and a job could be easily found. In 1956, father, mother, their four children, and granny Alexandra moved to Chelyabinsk. My father's exile friend and a native of Norka, Egor Schlidt (Georg Schlidt), returned to Zav'yalovo where he had left his family.

The family did not live in Chelyabinsk for long. They found jobs, but habitation was a big problem. At that time, beginning in 1954, the neighboring region of Kazakhstan was developing virgin lands and expanding greatly. Wild steppe was being ploughed up for grain-crops. New settlements were being built. Father decided to go to the virgin lands. They moved 300 km southeast from Chelyabinsk, in the Kostanay region of Kazakhstan. The family started living at the central farmstead of a new State farm named “Korzhunkolskiy.” The place was beautiful: woods and steppes, a wide clearing where a settlement began to be built. Around the farm there were birch and aspen woods and huge fields. That State farm was founded by volunteers from Moscow and Ukraine. There were a few German families who got there by different circumstances. There were only two or three Kazakh families out of several thousand people. In general, there were only a small number of Kazakh nationals in the Northern and Central parts of Kostanay region. Father bought an earth-house, and in a year he built a new house nearby. My father's sister, Nina, with her family later moved to us on the State farm. Uncle Fyodor stayed in Chelyabinsk with his sister Emma.

In 1959, Fyodor was called out for three years in the Soviet Army. In February 1959 I was born. Father was a master in a construction shop of the State farm; mother was a teacher in elementary school. My parents were respected in the village. Mother taught hundreds of children over these years. Father was elected a head of workers' trade union of the State farm in 1966. At that time, people were designated for such posts only by recommendation of the authorities, but they suggested honest and respectable people. My father as elected as a deserving candidate. He was not nominated for a second term, because it was very difficult to fight against the administration for workers' rights, and the authorities assigned him another job to remove him from the leadership of the trade union.

In 1962, Fyodor Schreiber returned from the Army. The same year he was married to a Russian woman in Chelyabinsk. Mother and father went to Chelyabinsk for the wedding and also took me there. In 1963, the first child was born in Fyodor's family - Vladimir Schreiber.

In 1965, my brother Victor finished the 8th grade and left home at the age of 15 years old. He started studying at a radio engineering college in the city of Sverdlovsk (now named Yekaterinburg).

In 1966, I began first grade. My first teacher was my mother. My parents were very modest, honest people. I was a talented boy. I read freely at age 5. I went to the village library by myself to check out books. Friends advised my parents to send me to school earlier. But they decided that they should be modest and I went to school together with my contemporaries at the age of seven years old. In autumn 1966, my elder brother Vladimir was called out into the Army. He served two and one-half years in the rocket forces, on the space-vehicle launching site Baikonur, as we learned later. In 1969, my brother Victor got married to a student from his group. In the same year, Victor’s first son, Aleksey Schreiber, was born.

In 1970, my brother Volodya got married too. He made his wife's town, Rudniy, his home. Rudniy was 50 km from our village. Volodya worked in geological expedition, studied in the Moscow Polytechnic Institute - Department of Mines. In 1971, my sister Galina got married. She moved to her husband’s family in another village. My sister Ida and I stayed together with our parents.

In 1971, a new town Lisakovsk began to be built 120 km from us. A layer of ironstone was found there and a big open-cast mine began to be dug. Small settlements were pulled down. Settlement Stepnoy was pulled down too. A lot of Germans lived there and part of this group was resettled in our village. A Nagel family moved here too. Their father was a native of Norka. I do not remember now how he got to Stepnoy. His sons, Iakov and Adam were my classmates.

On November 3, 1972 the Decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet: “Regarding Removal of the Restrictions in the Choice of Place of Residence, Provided in the Past for Some Categories of Citizens” was issued. The decree said:

1. To decline the restrictions in the choice of place of residence provided for the Germans and members of their families by the Decree of December 13, 1955.

2. To clarify that people whom this decree applies to, and members of their families, like all soviet citizens, have the right to choose their place of residence on the whole territory of the USSR in accordance with the legislation of placement in a job and passport regulations currently in force.

Thus, only at the end of 1972 were the Germans allowed formally to return home. The decree's two requirements: to be placed in a job and to fulfill passport regulations are very important. In the USSR, a person could not be employed if they did not have documentation in their passport confirming that they lived in the place employment. At the same time nobody was provided lodging in a new place if they could not show that they were employed there. To fulfill these two requirements at once was difficult.

In 1974, my parents went in Norka to find out of the situation there. When they went through the village one old Russian man called to my father: “Sashka!” The man immediately recognized my father after 33 years! Mother and father stayed in his house. In the evening two German women, Rosa and Natalia came to the house (their surnames are unfortunately forgotten). The women were wives of Russian men, and they were not evicted in the 1941. The old Russian man and women told my father what had happened with his house. During the war, refugees were placed in the houses of the evicted Germans. The refugees seemed to be Hebrews (Jews) from Ukraine who had been moved there during the war. Living in large German houses, they first cut and burned down the orchards and gardens in their stoves, then they burned houses. Having burned down half of one house, they moved to a neighboring house and burned out the rest of the house. This cycle repeated until the whole residential area was ruined in this way. Father found the place where his house had been situated. There were only ruins all around. The whole part of the village where my father had lived had been turned into waste land. There was no place to return to. Nobody was waiting for the Germans to come back, nobody was calling them to return, and nobody was going to give back the plunder.

Officially, the property and personal belongings of the evicted Germans was not confiscated in 1941. The local authorities gave receipts to the evicted Germans showing that their property was being passed to them in trust until they returned. But these turned out to be just meaningless bits of paper. The authorities have lost these receipts long ago, and say they do not remember them, but some German families keep them for memory.

In 1974, my parents went in Norka to find out of the situation there. When they went through the village one old Russian man called to my father: “Sashka!” The man immediately recognized my father after 33 years! Mother and father stayed in his house. In the evening two German women, Rosa and Natalia came to the house (their surnames are unfortunately forgotten). The women were wives of Russian men, and they were not evicted in the 1941. The old Russian man and women told my father what had happened with his house. During the war, refugees were placed in the houses of the evicted Germans. The refugees seemed to be Hebrews (Jews) from Ukraine who had been moved there during the war. Living in large German houses, they first cut and burned down the orchards and gardens in their stoves, then they burned houses. Having burned down half of one house, they moved to a neighboring house and burned out the rest of the house. This cycle repeated until the whole residential area was ruined in this way. Father found the place where his house had been situated. There were only ruins all around. The whole part of the village where my father had lived had been turned into waste land. There was no place to return to. Nobody was waiting for the Germans to come back, nobody was calling them to return, and nobody was going to give back the plunder.

Officially, the property and personal belongings of the evicted Germans was not confiscated in 1941. The local authorities gave receipts to the evicted Germans showing that their property was being passed to them in trust until they returned. But these turned out to be just meaningless bits of paper. The authorities have lost these receipts long ago, and say they do not remember them, but some German families keep them for memory.

My parents returned to Kazakhstan. My sister Ida finished school and then attended college in Rudny. She later moved to Lisakovsk. In 1975, Ida was married to a German man named Alexander Stark. The same year she gave birth to her son Vitaly. In 1976, I finished the 10th grade of school. In May 1977, I was called into the Soviet Army and served near the city of Alma-Ata, in Kazakhstan. In May 1977, I came home.

On May 31, 1979, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CC CPSU) passed the “Decree Regarding the Foundation of the German Autonomous Region”. This decree was not published in press. A German region was going to be founded in the territory of Kazakhstan with the capital placed in the city of Ermentau (not far from today’s capital of Astana, Kazakhstan). It was planned that the German region would include five areas of the four neighboring regions of Kazakhstan. Drafts of all laws and decrees were prepared. Part of the Kazakhstan population learned of the preparations for the constitution of the German region. On the 16th, 17th and 22d of June in the city of Celinograd (later Astana and now Nur-Sultana) protest demonstrations were organized, by whom remains a mystery. Those present at the protests were mostly Kazakh students. Their slogans: “Let's not give up our land to the fascists. Send all the Germans back into Siberia. Restore the special commandant's office (this special office was involved in surveillance of the Germans)”. Four Germans were wounded and killed. The formation of the autonomous German region was postponed.

In 1980, I entered the Moscow Geological Institute. By that time my brother Vladimir graduated from the institute and moved with his family in Komi Republic, in the town Pechora, to help build the large Pechora hydroelectric power station. Vladimir had three children: Inna, Yulia, and Anton Schreiber. My brother Victor graduated from the Urals Polytechnic Institute in Yekaterinburg, radio engineering department, extra-mural. Victor lived in the city of Polevskoy, near Yekaterinburg. He had two sons: Aleksey and Andrey Schreiber. In 1982, my parents moved to Kostanay. Brother Vladimir presented them his former flat. Father was very proud that his children, especially his sons, received a good education, because he had not managed to get a deserved education early in life. On graduation from the institute in 1985, I went to work in Siberia, in Chita region, the city of Krasnokamensk. I worked in the geological service of the largest uranium industrial complex in the USSR. I brought my wife Anna and daughter Galina (born in 1983) with me.

When Mikhail Gorbachev took power in 1985, especially from 1987 to 1988, democratic changes began in the USSR. I was an active member of a democratic movement. My associates and I established an independent political organization with a Democratic initiative in our city. We took part in all the election campaigns, organized our own group in the city's parliament. I was nominated for the mayor of the city, the elections should have been held in the autumn of 1991. We had a good chance to win the elections. But President Boris Yeltsin abolished the elections all over Russia, and the heads of the cities and regions were appointed by Moscow. Almost everywhere, the appointed government heads were former communists. In January 1992, the economic reforms started and life became very difficult in Siberia. I returned to Moscow.

On May 31, 1979, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CC CPSU) passed the “Decree Regarding the Foundation of the German Autonomous Region”. This decree was not published in press. A German region was going to be founded in the territory of Kazakhstan with the capital placed in the city of Ermentau (not far from today’s capital of Astana, Kazakhstan). It was planned that the German region would include five areas of the four neighboring regions of Kazakhstan. Drafts of all laws and decrees were prepared. Part of the Kazakhstan population learned of the preparations for the constitution of the German region. On the 16th, 17th and 22d of June in the city of Celinograd (later Astana and now Nur-Sultana) protest demonstrations were organized, by whom remains a mystery. Those present at the protests were mostly Kazakh students. Their slogans: “Let's not give up our land to the fascists. Send all the Germans back into Siberia. Restore the special commandant's office (this special office was involved in surveillance of the Germans)”. Four Germans were wounded and killed. The formation of the autonomous German region was postponed.

In 1980, I entered the Moscow Geological Institute. By that time my brother Vladimir graduated from the institute and moved with his family in Komi Republic, in the town Pechora, to help build the large Pechora hydroelectric power station. Vladimir had three children: Inna, Yulia, and Anton Schreiber. My brother Victor graduated from the Urals Polytechnic Institute in Yekaterinburg, radio engineering department, extra-mural. Victor lived in the city of Polevskoy, near Yekaterinburg. He had two sons: Aleksey and Andrey Schreiber. In 1982, my parents moved to Kostanay. Brother Vladimir presented them his former flat. Father was very proud that his children, especially his sons, received a good education, because he had not managed to get a deserved education early in life. On graduation from the institute in 1985, I went to work in Siberia, in Chita region, the city of Krasnokamensk. I worked in the geological service of the largest uranium industrial complex in the USSR. I brought my wife Anna and daughter Galina (born in 1983) with me.

When Mikhail Gorbachev took power in 1985, especially from 1987 to 1988, democratic changes began in the USSR. I was an active member of a democratic movement. My associates and I established an independent political organization with a Democratic initiative in our city. We took part in all the election campaigns, organized our own group in the city's parliament. I was nominated for the mayor of the city, the elections should have been held in the autumn of 1991. We had a good chance to win the elections. But President Boris Yeltsin abolished the elections all over Russia, and the heads of the cities and regions were appointed by Moscow. Almost everywhere, the appointed government heads were former communists. In January 1992, the economic reforms started and life became very difficult in Siberia. I returned to Moscow.

In February 1989, my father received an answer from Saratov to his request for information about Grandfather Conrad's fate. For the first time our family learned that grandfather was shot in 1937. In 1964, grandfather had been rehabilitated by the Saratov regional court. Grandfather's arrest and his execution were declared illegal. In 1964, the court informed the local militias of Altai region about this matter and asked them to tell our family about this decision. Unfortunately, by that time, our family had left the Altai region and we were not informed about grandfather’s fate.

To the end of the 1980’s, a movement for reestablishment of the autonomy on Volga began among the Germans. In 1987, in the territory of Saratov region there lived 19,000 Germans (in 1979 - 11,000). This totaled 0.64% of the whole region's population, this figure was over 20% before the Second World War. The largest part of Germans lived in Markovsky (4,100), Engelsky (3,000), and Krasnoarmeysky (former Balzer) (2,500) areas. The inner structure of the population had changed greatly in comparison with that before World War II, including the quality of the inhabitants. The region was now home to many former criminals. There were now a number of medical dispensaries (prisons for drunkards and the like) along with maximum and medium security prisons. The Supreme Soviet of the USSR organized a commission in the matter of the Soviet Germans. Documents for reconstruction of the autonomous republic on the Volga were being prepared. But the local communist leaders in Saratov region raised opposition from the Russian people to autonomy for Germans. The Supreme Soviet's Commission visited Saratov region in November 1989. The population of Marksovsky and Krasnoarmeysky areas opposed the autonomy most of all, especially veterans and elderly people. At the meeting with deputies in Krasnoarmeysky at the Palace of Culture, there were 500 people in the hall and 3,000 people in the street. Veterans spoke in the hall, and their speeches were broadcast into the street. The crowd in the street passionately upheld the slogans: “Stalin was right to have evicted the Germans. Among the Volga Germans, Hitler’s fifth column was really being formed. We keep finding weapons and radio receivers in garrets and cellars of the houses. The Vozrozhdenie Society (German Rebirth Society) is a group of pretenders, these people express anti-people, counterrevolutionary, nationalist views, these are brand new Bormanns', Hitlers', Goebbels'. If Moscow wants to establish German autonomy, then let it be somewhere in uninhabited places.” The government deputies left the Palace of Culture through the backdoor.

Nevertheless, Mikhail Gorbachev was moving to reconstruct an autonomous German region on the Volga. A State commission was organized on the 29th of January 1990 to find a solution to the “German problem”. On April 5, 1990, the Altai region deputies' counsel came out in favor of reconstructing the autonomy of the Volga Germans. At that time 128,000 Germans lived in Altai. On April 6, 1990, the Ulyanovsk region deputy counsel invited all Germans living in the Soviet Union to find permanent residence in their region. During negotiations with Germany, the Soviet powers confirmed their intention to reestablish the autonomy on Volga Germans. On May 7, 1991, the Russian State leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, for the first time received a delegation of Soviet Germans. In August 1991, there was a putsch in Russia. Before winter began, Gorbachev was dismissed from the post of President. The new President of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, visited the Saratov region and claimed: “In those places where there is no German compact living, that is, where they are not an overwhelming majority, to 90%, there will be no autonomy! I guarantee this to you as President!” I was listening to this speech on a live TV program. It was clear that the new government powers had rejected all its promises to reconstruct an autonomous region for the Volga Germans.

As hope for autonomy evaporated, the stream of emigration to Germany increased sharply. At that time I was living in Moscow. I took part in the work of the German society “Vozrozhdenie” (“Rebirth”) that was working to revive the Volga German Republic. Many leaders of the society migrated to Germany, as well as many of my friends. In May 1994, at the Domodedovo Airport in Moscow, I saw off my Aunt Emma with her husband Conrad and her elder son's family to Germany. In 1997, Aunt Emma's daughters and their families, my cousins Irina and Lida, emigrated too. This year Aunt Emma is 80, she lives in the German State of Baden-Württemberg, in the city of Albstadt.

To the end of the 1980’s, a movement for reestablishment of the autonomy on Volga began among the Germans. In 1987, in the territory of Saratov region there lived 19,000 Germans (in 1979 - 11,000). This totaled 0.64% of the whole region's population, this figure was over 20% before the Second World War. The largest part of Germans lived in Markovsky (4,100), Engelsky (3,000), and Krasnoarmeysky (former Balzer) (2,500) areas. The inner structure of the population had changed greatly in comparison with that before World War II, including the quality of the inhabitants. The region was now home to many former criminals. There were now a number of medical dispensaries (prisons for drunkards and the like) along with maximum and medium security prisons. The Supreme Soviet of the USSR organized a commission in the matter of the Soviet Germans. Documents for reconstruction of the autonomous republic on the Volga were being prepared. But the local communist leaders in Saratov region raised opposition from the Russian people to autonomy for Germans. The Supreme Soviet's Commission visited Saratov region in November 1989. The population of Marksovsky and Krasnoarmeysky areas opposed the autonomy most of all, especially veterans and elderly people. At the meeting with deputies in Krasnoarmeysky at the Palace of Culture, there were 500 people in the hall and 3,000 people in the street. Veterans spoke in the hall, and their speeches were broadcast into the street. The crowd in the street passionately upheld the slogans: “Stalin was right to have evicted the Germans. Among the Volga Germans, Hitler’s fifth column was really being formed. We keep finding weapons and radio receivers in garrets and cellars of the houses. The Vozrozhdenie Society (German Rebirth Society) is a group of pretenders, these people express anti-people, counterrevolutionary, nationalist views, these are brand new Bormanns', Hitlers', Goebbels'. If Moscow wants to establish German autonomy, then let it be somewhere in uninhabited places.” The government deputies left the Palace of Culture through the backdoor.

Nevertheless, Mikhail Gorbachev was moving to reconstruct an autonomous German region on the Volga. A State commission was organized on the 29th of January 1990 to find a solution to the “German problem”. On April 5, 1990, the Altai region deputies' counsel came out in favor of reconstructing the autonomy of the Volga Germans. At that time 128,000 Germans lived in Altai. On April 6, 1990, the Ulyanovsk region deputy counsel invited all Germans living in the Soviet Union to find permanent residence in their region. During negotiations with Germany, the Soviet powers confirmed their intention to reestablish the autonomy on Volga Germans. On May 7, 1991, the Russian State leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, for the first time received a delegation of Soviet Germans. In August 1991, there was a putsch in Russia. Before winter began, Gorbachev was dismissed from the post of President. The new President of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, visited the Saratov region and claimed: “In those places where there is no German compact living, that is, where they are not an overwhelming majority, to 90%, there will be no autonomy! I guarantee this to you as President!” I was listening to this speech on a live TV program. It was clear that the new government powers had rejected all its promises to reconstruct an autonomous region for the Volga Germans.

As hope for autonomy evaporated, the stream of emigration to Germany increased sharply. At that time I was living in Moscow. I took part in the work of the German society “Vozrozhdenie” (“Rebirth”) that was working to revive the Volga German Republic. Many leaders of the society migrated to Germany, as well as many of my friends. In May 1994, at the Domodedovo Airport in Moscow, I saw off my Aunt Emma with her husband Conrad and her elder son's family to Germany. In 1997, Aunt Emma's daughters and their families, my cousins Irina and Lida, emigrated too. This year Aunt Emma is 80, she lives in the German State of Baden-Württemberg, in the city of Albstadt.

In February 1993, my father had received a “Certificate of Rehabilitation” from Perm. The government had belatedly found that father was a victim of the political repressions. In the end of March 1993, the Kostanay Municipal Deputy Counsel gave my father, as a victim of the repressions, a certificate for certain privileges. Within five months, father passed away. In the last years of his life, when he was not young any more, people gave him a place to stand in shop queues, saying: “Go forward. You must be a veteran of the war”. These moments were bitter for my father, he said: “No, I wasn't at the war” and remained standing in his place, declining their offer.

Not long before the departure of Aunt Emma in 1993, my father died. He was ill the last years of his life. He died on the 29th of August 1993 in Kostanay. We buried him on the 1st of September, the birthday of my sister Ida, in her hometown of Lisakovsk. It was a cold autumn day. In the bed of a truck, in the open air, my three brothers and I went with our father who was lying in a coffin.

Not long before the departure of Aunt Emma in 1993, my father died. He was ill the last years of his life. He died on the 29th of August 1993 in Kostanay. We buried him on the 1st of September, the birthday of my sister Ida, in her hometown of Lisakovsk. It was a cold autumn day. In the bed of a truck, in the open air, my three brothers and I went with our father who was lying in a coffin.

Emigration to Germany was also very strong from Kazakhstan. In 1993, I saw people crying as they parted from almost every railway station in the Kustanay region. The whole German settlement became deserted. A bad economic situation and domination of Kazakh people in the leadership of the country made people decide to leave. The leaders of Kazakhstan changed the national structure of the population deliberately. The capital of the republic was moved to the North in Astana. Kazakhs from Mongol republics were brought into the abandoned German settlements. The educational and cultural level of the Mongol Kazakhs is much lower than those who had gone away.

In the beginning of the 1990’s, the German Red Cross compiled lists of the Soviet Germans who worked in Stalin’s camps. Since that time, they helped father and later mother by sending parcels of clothes and food. Mother informed the German Red Cross of my father's death, but help continues to come addressed to my mother now. This characterizes the German attitude to the victims, as distinct from the Russian one.

In 2001, my elder brother Vladimir perished in a car accident during his holidays in Yekaterinburg. He is buried in the city Pechora of the Komi republic. There his daughter Yulia and younger daughter Oksana of our sister Galina live. His daughter Inna and son Anton live in Perm. Victor still lives in Polevsky. His elder son Aleksey lives in Yekaterinburg, as well as daughter Lena of our sister Ida. Victor’s younger son, Andrey Schreiber, lives in Vladivostok. Our sister Galina lives with her daughter Tanya in the village Fyodorovka of Kostanay region of Kazakhstan. In Chelyabinsk, uncle Fyodor lives with his two sons Vladimir and Gennady. The younger son of Aunt Emma Urbach (nee Schreiber), Alexander Urbach, stayed in Chelyabinsk too. In 2001, a month before Vladimir's death, Aunt Nina died in Lisakovsk. She is buried at the same graveyard with my father. Aunt Nina left five children: Alexander, Lida, Vladimir, Valentina, and Anatoly. The elder son of Lida also emigrated in Germany. Sister Ida lives in Lisakovsk with her son Vitaly and my mother. I live in Moscow and my daughter Galina is finishing her studies at the Moscow State Chemical-Technological University this year.

In the beginning of the 1990’s, the German Red Cross compiled lists of the Soviet Germans who worked in Stalin’s camps. Since that time, they helped father and later mother by sending parcels of clothes and food. Mother informed the German Red Cross of my father's death, but help continues to come addressed to my mother now. This characterizes the German attitude to the victims, as distinct from the Russian one.

In 2001, my elder brother Vladimir perished in a car accident during his holidays in Yekaterinburg. He is buried in the city Pechora of the Komi republic. There his daughter Yulia and younger daughter Oksana of our sister Galina live. His daughter Inna and son Anton live in Perm. Victor still lives in Polevsky. His elder son Aleksey lives in Yekaterinburg, as well as daughter Lena of our sister Ida. Victor’s younger son, Andrey Schreiber, lives in Vladivostok. Our sister Galina lives with her daughter Tanya in the village Fyodorovka of Kostanay region of Kazakhstan. In Chelyabinsk, uncle Fyodor lives with his two sons Vladimir and Gennady. The younger son of Aunt Emma Urbach (nee Schreiber), Alexander Urbach, stayed in Chelyabinsk too. In 2001, a month before Vladimir's death, Aunt Nina died in Lisakovsk. She is buried at the same graveyard with my father. Aunt Nina left five children: Alexander, Lida, Vladimir, Valentina, and Anatoly. The elder son of Lida also emigrated in Germany. Sister Ida lives in Lisakovsk with her son Vitaly and my mother. I live in Moscow and my daughter Galina is finishing her studies at the Moscow State Chemical-Technological University this year.

In August 2004, our whole family gathered in Lisakovsk. On the 29th of August we bowed to the graves of my father and Aunt Nina. On the 1st of September we celebrated the 50th birthday of Ida. I watch the video recording from this celebration in sorrowful moments and remember all the Schreiber's.

In 2004, I was lucky to find the offspring of the Schreiber's in the USA. My father and brother Vladimir had dreamt of this many times, but they did not live to see this day. I ask all offspring of the Schreiber's from Norka, offspring of my grandfather's brothers, Georg and Peter, to respond. I will be glad to get acquainted with them and meet with them in Russia.

In 2004, I was lucky to find the offspring of the Schreiber's in the USA. My father and brother Vladimir had dreamt of this many times, but they did not live to see this day. I ask all offspring of the Schreiber's from Norka, offspring of my grandfather's brothers, Georg and Peter, to respond. I will be glad to get acquainted with them and meet with them in Russia.

Postscript 1:

In September 2004, a monument to the victims of the Trud Armee (labor army) was opened in the metallurgical area of the city of Chelyabinsk. The monument was placed where the working barracks were located during and after the war. Most of the people living and working in the barracks were German Russians, including my aunt Emma and her husband, Conrad Urbach. My uncle Feodor also lives in the same area of the city with other relatives. There are now new houses on this site.

In September 2004, a monument to the victims of the Trud Armee (labor army) was opened in the metallurgical area of the city of Chelyabinsk. The monument was placed where the working barracks were located during and after the war. Most of the people living and working in the barracks were German Russians, including my aunt Emma and her husband, Conrad Urbach. My uncle Feodor also lives in the same area of the city with other relatives. There are now new houses on this site.

The artist who created the monument is Vincent Schreiner from Austria. The monument depicts Jesus Christ and a wreath made from barbed wire. An inscription behind the figure of Christ reads: "I live that you may also live". A black altar is in front of Christ holding the bones of the martyrs. Under the altar is a capsule with the remains of an unknown person.

There were many people at the opening of the monument including German Russians now living in Germany, but none of the officials from the city of Chelyabinsk and the surrounding areas attended.

Hubert Vitlif, a German victim of the camps, recollects: "For me it was 20 years. We were lodged in holes dug in the ground. Above the ground there was only a roof and 80 centimeters of a wall. Snow, ice, plank beds from rough boards... The sledge hammer, pick, shovel and a stretcher. Here, for the first time I learned to dig the frozen ground at temperature of minus 30 degrees centigrade. We rose early in the morning. Under the watch of armed security forces we went to work. We came back to camp with the approach of darkness. Many could not maintain themselves and died. The rations given to us were less than those given to prisoners of war. In the morning we were given water with cabbage and 200 grams of bread..."

In the metallurgical area of Chelyabinsk there were 18 camps that held up to 50,000 Russian Germans. Tens of people died daily. These people were buried at night in unmarked graves. Until now, no memorial or monument has been placed at these cemeteries.

Hubert Vitlif recalls: "Once a comrade and I were ordered to take a sleigh full of dead men out from the camp. At the checkpoint was a security guard with an automatic weapon and metal stick in his hands. To all the people laying in the sleigh the guards punched a 'control' hole in their heads to insure they were dead. We drove 4 kilometers away from the camp. The earth was frozen and people were piled up - almost not buried. Around the area dogs and wolves wandered. In the afternoons, local boys played with balls that were actually German skulls. Later, the boys learned that the skulls and bones could be sold to the medical institute for 20 rubles a piece and a business began."

There were many people at the opening of the monument including German Russians now living in Germany, but none of the officials from the city of Chelyabinsk and the surrounding areas attended.

Hubert Vitlif, a German victim of the camps, recollects: "For me it was 20 years. We were lodged in holes dug in the ground. Above the ground there was only a roof and 80 centimeters of a wall. Snow, ice, plank beds from rough boards... The sledge hammer, pick, shovel and a stretcher. Here, for the first time I learned to dig the frozen ground at temperature of minus 30 degrees centigrade. We rose early in the morning. Under the watch of armed security forces we went to work. We came back to camp with the approach of darkness. Many could not maintain themselves and died. The rations given to us were less than those given to prisoners of war. In the morning we were given water with cabbage and 200 grams of bread..."