Johann Baptist Cattaneo Memoirs

Preface

The following memoirs stem from the pen of one of the first historiographers of the Volga colonies. To be sure, they are only fragments of the active and rich life of an exceptionally educated and gifted man of the era. He devoted himself to the spiritual care of our immigrated ancestors and was always a ready friend and advisor. He was the first formally trained physician in the Volga region. His good name extended beyond the colonies' borders into the steppes of the Kalmyk tribes. Even today, the 'alte Katane' (old Catteneo) lives on in the reverent memory of our people. These memoirs were first published in the 1875 edition of the Wolga-Kalender - most likely contributed by Cattaneo's successor as pastor in Norka, Samuel Bonwetsch. Pastor Bonwetsch's pen also produced notable annals of the Reformed Church in the Volga colonies; these have been preserved in my possession and will appear in a later edition of this journal. P. S

The following memoirs stem from the pen of one of the first historiographers of the Volga colonies. To be sure, they are only fragments of the active and rich life of an exceptionally educated and gifted man of the era. He devoted himself to the spiritual care of our immigrated ancestors and was always a ready friend and advisor. He was the first formally trained physician in the Volga region. His good name extended beyond the colonies' borders into the steppes of the Kalmyk tribes. Even today, the 'alte Katane' (old Catteneo) lives on in the reverent memory of our people. These memoirs were first published in the 1875 edition of the Wolga-Kalender - most likely contributed by Cattaneo's successor as pastor in Norka, Samuel Bonwetsch. Pastor Bonwetsch's pen also produced notable annals of the Reformed Church in the Volga colonies; these have been preserved in my possession and will appear in a later edition of this journal. P. S

I

On the 22nd of July, 1763, Catherine the Second published a Manifesto inviting foreign settlers to relocate to Russia. Thereupon, our ancestors immigrated to this foreign land and found a new home on the banks of the Volga. They brought with them from their old home, above all else, something more precious than the finest gold--namely, the faith of their fathers and the unadulterated gospel. In this respect, they were exceptionally fortunate because a drought of faithlessness befell Germany not long after their departure. At the same time, the settlers on the Volga enjoyed the care of faithful shepherds of the soul who believed in Christ. One of these was Johann Baptist Cattaneo, of whom this chronicler would now like to recount some details--or, more accurately, allow him to tell some of his own story. I will only preface a few things as an introduction to his own words.

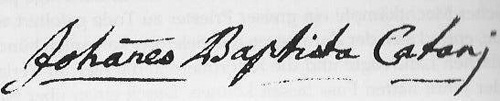

Johannes Baptista Cattaneo (Johann Baptist Cattaneo) was born on the 27th of June, 1746, in Lavin, a small village in the Unter-Engadin area of the Swiss canton of Graubünden. His god-fearing parents, Thomas and Ursula Cattaneo, intended him for the ministry from the beginning. They taught him short prayers, verses from hymns, and religious sayings from an early age. Beginning at age 7, he went to the village school and learned to read, write, sing, and acquaint himself with Hubner's biblical stories. Then his father died in 1755. Cattaneo's guardian, the pastor Sebastian Sekka, assumed responsibility for his education. Later in life, Cattaneo often fondly recalled the blessing he found in preparing for his first communion. After 2 years of education with his erudite uncle Peter von Porta, Cattaneo left for the university in Zürich to pursue divinity studies. While boarding there with a physician, he found opportunities to acquire medical training, especially in surgery. In 1766, Cattaneo completed his studies with the highest honors and became pastor in Fläsch, where he was blessed to work for 4 years. After a subsequent 1-year service in Tschuders, he was called to be pastor in St. Anthony, where he remained for 13 years. In the meantime, he had married in 1770. Then, while on a trip to Chur in 1784, he was unexpectedly called to serve as pastor in Norka. He accepted the post and departed for the Volga on the 5th of May in the same year with his wife and 6 children. He arrived on the 3rd of August, 1784.* He served in Norka with an occasional hiatus until the 15th of March, 1828, and then died peacefully in his sleep on the morning of January 16, 1831.

During his first year in Russia Cattaneo wrote a small book well worth reading: "Eine Reise durch Deutschland und Rußland, seinen Freunden beschrieben von Johann Baptista Cattaneo aus Bünden, gegenwärtigem Pfarrer einer reformierten deutschen Colonie zu Norka in der Saratowischen Statthalterschaft an der Wolga in der russischen Tatarey in Asien. Chur 1787". In this work, the author describes the impressions he gathered in the various lands he traversed on the journey. He presents especially valuable material about the conditions in Russia at that time. A postscript offers a cultural description of the colonies on the Volga. This small book has been out of print for a long time and is only available at a handful of specialty bookshops. P. S.

II

Now, we should let Cattaneo speak for himself. Unfortunately, the beginning of his memoirs has been lost, so his accounts begin with the numerous trips he was obliged to undertake to the widespread Reformed communities. --

Night fell during one of my trips to Pobochnaya, and I unexpectedly stumbled across 10 to 12 unsavory characters -- Russians -- standing near some saddled horses. I had often been told that the woods near the Moscow highway harbored bandit gangs, and I did not doubt these wood folk were one of those. It was too late to make an escape because they had already noticed us; to approach them seemed a risky proposition. Nonetheless, I decided for the latter, strapped on my saber, equipped myself with a pair of loaded pistols, and made a stouthearted approach to their fire with my waggoneer following along. There was embarrassment on both sides. We at the prospect of this sizable little group, and they because they feared us to be officials of the Inquisition on the hunt for heretics, reinforced by a sizable contingent just down the road. Even though I did not attempt to dissemble and I openly answered their inquiries into the nature of our journey, they remained uncertain. I smoked my pipe peacefully in the back of my wagon and awaited the morning. But when it started to dawn, the others beat a hasty departure without molesting us. -- This occurred in the summer of 1788, and no one has heard from the bandits since.

Fellowship with the more remotely situated Germans I served was all the more pleasant since it happened infrequently. I found many opportunities to serve both the body and the soul of my fellow man. Although I often experienced adversity on those journeys, the joys of my service caused me to forget the difficulties, and I never feared to undertake future trips.

In 1791, during the winter, my wagoner and I lost our way on the other side of the Volga in the trackless steppes. Night fell, and we had to camp in the snow as best we could. In the morning, we found our way again and arrived at the next colony after a detour of about 30 versts. -- In the winter of 1816, we had to spend another night in the field during a heavy blizzard. I was in the colony of Splauwnucha (Huck), located about 10 versts from Norka, and departed from there in the afternoon in a heavy snowstorm. The weather steadily deteriorated, becoming especially dangerous for us because the wind drove the snow into our faces. After a long and arduous journey, I thought we had reached the outskirts of Norka. But once again, we lost our way, although we had already been underway for hours. In fact, we could no longer make any progress because the cold and the icy surface caused our horse to become unhitched; our wagoner could no longer re-hitch the horse again and again. Also, the horse was exhausted. We set up camp as night had long since fallen, and we found ourselves in unknown territory. I settled down in the snow, but the wagoner declared he could not hold out here; he had become overheated from repeatedly hitching the horse, and now he was freezing in his sweaty clothes. He set out again and fortunately found Norka. Then, people came out from the colony to search for me and brought me home at about 1:00 in the morning. -- In 1790, I was on the way to Splawnucha (Huck) across the Mühlen-See lake--the usual route between the two colonies in winter. But I broke through the ice and was thrown in. The necessities, my bedding, and my furs helped me to stay afloat and swim to shore. The wagoner safely stationed on the opposite bank with his sleigh watched all this frozen with horror while I froze from the cold. We eventually reached the colony about 2 versts further on, where I recovered without any ill effects.

In the spring of 1798, after the water had receded some, I was dragged into the water at the same location in half of a carriage--we had lost the rear axle and wheels in the descent of the bank. But the horse pulled the floating front half onto the other shore, where the nail broke that joined the rest of the wagon to the front. And so good fortune once again allowed me to sit high and dry after another adventure. I had to view it as a miracle of divine providence, as in so many other perils, to escape unscathed. To God be all praise and thanks!

In 1805, I took my son Lukas by post coach to the Imperial University in Dorpat, Livonia, about 2,000 versts from here. We had many good experiences in Moskow, St. Petersburg, and Dorpat. Our educational plans received especially generous support from His Imperial Majesty in St. Petersburg, and my son was graciously awarded a stipend of 1,200 rubles for his 3-year course of study. It was more than suitable that I should demonstrate my appreciation for this generosity by continuing my work of inoculating the population of every German village on the Volga against smallpox, a task I had already begun at the imperial request. After I had inoculated 8,000 children, His Majesty most graciously awarded me a gilded tobacco canister and, later, the cross of the Order of St. Vladimir to wear on my breast. My aforementioned son Lukas took his exams in St. Petersburg in 1808 after finishing his studies, was ordained to the ministry, and in accordance with my wishes, was assigned as my assistant. In the spring of 1809, he was called by official decree to serve as a preacher in the evangelical congregations in Astrakhan. After 2 years there, he returned to me with his wife and child, where he lived with me at my expense as an unpaid assistant until 1817. In that year, I appealed to the judicial council to be relieved of the duties that had become too burdensome for me. My request was granted, and my son was installed as my successor.

For 33 years, I have served this parish and have been an active pastor for 51 years. Now, I devote myself entirely at my convenience to spiritual duties since my 73 years remind me emphatically that my strength is diminishing. I continue my medical practice daily as there is always a need.

III

The Lord has also richly blessed me in this work. With humble thanks, I give testament: Lord, You are the Master; we are only poor tools in Your Hand. Among the many operations I performed up to 1819, I've noted down 16 amputations of arms, legs, fingers, etc., from which all recovered happily. I have treated 27 cases of cancer of the mouth, face, neck, and breast, which were operated on, and all were well-healed. Many who suffered from dropsy and sought timely help were restored to health. Other growths on various parts of the body, as well as many internal and external wounds and infirmities, were frequently cured. In my medical practice, I have always sought to employ the simplest medications and means to save myself and the patient's costs, for the simplest methods often lead to better recovery than do the expensive, more elaborately compounded medications.

I would like to relate several extraordinary cures because of their unusual nature.

The headman in Splawnucha (Huck) notified me about a colonist in his village who was so melancholy that he constantly talked of suicide and didn't do any work at all. Hence, the community had heeded an official decree for the past several years to feed him and his family. I visited the supposed invalid to hear his confession and tried to help him. But the man found his situation all too agreeable and showed no improvement. Finally, I had my fill, as had the entire village for some time already. I recruited four stalwart, honorable men from the village and went with them to visit the man. After discussing strategy with my four helpers beforehand, I proceeded to tell the man in no uncertain terms that he had sinned long enough by threatening for years to commit suicide and that the entire community considered him to be a suicide already. So it was high time he carried through with his threats; he had already burdened his fellow colonists long enough. We had come to be witnesses. I was ready to report back on his successful suicide, and he should get on with it and complete the devilish deed on the spot. With some difficulty, we got the well-fed fellow into his clothes. But before we finished, he began to haggle and bargain. First, he requested that we throw him in the water. This we immediately rejected as we desired no part of the sinful act of suicide. Finally, he asked for patience and promised to commit suicide by his own hand. We consented. But then, after more discussion, we all reached an agreement: he promised from that hour hence to return to his work and never threaten suicide again. He kept his word and has lived for some years since an orderly, respectable life, and worked to support himself and his family.

A colonist in Warenburg came to me and lamented the miserable condition of his 30-year-old daughter. Because of her delicate physical nature, she was spared from working in the fields. But since she had a good religious education and aptitude, she began giving religious instruction to children in addition to her normal feminine pursuits. In other respects, she led a quiet, decent life. Recently, she had begun to develop the peculiar and regrettable habit of mixing together the most sacred and profane behavior. She sang and prayed, laughed and danced, and bestowed the gentlest and most sentimental caresses on male passers-by. Amidst all this craziness, she acted as if this were the most normal thing in the world. And so I consented for her to be brought to our home in Norka, where she wreaked havoc day and night for several weeks. No medicines had any effect. Then, during one night--it was between Saturday and Sunday--she took everything that was not nailed down in the house and put it on display on the graves in the nearby cemetery. This was the last straw. I threatened to give her a good thrashing the next time she pulled such a stunt. But she behaved cute, as she did after every misdeed like this, and was convinced I would not carry through on my promise. The following night, her insane, self-supposed religious behavior was more deranged than ever. I kept my word and gave her a sound beating on the spot. She crept off--and was cured. Never again did she behave indecently or cantankerously. From that day, she led a quiet, upright, exemplary life.

Once, the Norka villager B. brought me his unmarried daughter, who was of age but insane. I found it necessary to open a vein in her foot to bleed her. The moment she saw blood, she began incessantly to scream at the top of her lungs to have the foot bandaged. When she was ignored, she exclaimed she was dying. Immediately, she fell down and screamed: I am dead, I am dead. Then she began to play the corpse. Her father suffered terrible fits of anxiety, but I reassured him and demanded we begin on the spot to prepare for the burial. I asked a man who was present to have a grave prepared, arrange for pallbearers, etc. The dead woman heard all this and not only resurrected but jumped up and hurried out the door and across the yard with the unbandaged foot. Her father had to exert himself considerably to catch up with her. She was cured, married later on in Norka, and never again showed a trace of mental illness.

Now, it seems probable I'll reach the end of my earthly journey before long--a journey filled with sin but redeemed by Christ. And so it is with humble and heartfelt thanks to my beloved Lord that I exclaim: You have shown me more patience, grace, and mercy than I can comprehend! I am of ashes and earth; what value am I? Nothing in me is of value other than what was accomplished by the blood of Jesus. He has loved me so! Oh God, what a gift of love and mercy I have in His death! How do I thank Him now? What can I do for Him? Oh, if only every drop of my blood could be hallowed to honor Him! -- Norka, March 27, 1819.

Today is April 30, 1826, and I am still healthy. Since I am well and, by the grace of the Lord, still strong and active, it seems fitting that I should append the following.

In 1821, in the middle of March, the recently established Evangelical Synod in Saratov undertook an extensive reorganization of the various preachers and parishes. This resulted in my son, Lukas, going as pastor to the Talowka (Beideck) parish and the parish in Norka unanimously asking me, this old preacher, not to abandon them as long as I should still live. I decided to consent to their wishes. Since then, I have been their sole preacher and spiritual shepherd. And by the grace of the Lord, I have remained healthy and able to fulfill all pastoral duties promptly and faithfully! In July 1825, I visited the Brethren in Sarepta and enjoyed celebrating my 80th birthday with my children. I then returned in good health and reinvigorated to my beloved parish, where I stand ready to live or die according to the will and mercy of the Lord. May He grant me the consolation of my faith: I know in whom I believe, and He will delay my burial until the appointed time.

Thus, this ends the memoirs of J. B. Cattaneo.

On the 22nd of July, 1763, Catherine the Second published a Manifesto inviting foreign settlers to relocate to Russia. Thereupon, our ancestors immigrated to this foreign land and found a new home on the banks of the Volga. They brought with them from their old home, above all else, something more precious than the finest gold--namely, the faith of their fathers and the unadulterated gospel. In this respect, they were exceptionally fortunate because a drought of faithlessness befell Germany not long after their departure. At the same time, the settlers on the Volga enjoyed the care of faithful shepherds of the soul who believed in Christ. One of these was Johann Baptist Cattaneo, of whom this chronicler would now like to recount some details--or, more accurately, allow him to tell some of his own story. I will only preface a few things as an introduction to his own words.

Johannes Baptista Cattaneo (Johann Baptist Cattaneo) was born on the 27th of June, 1746, in Lavin, a small village in the Unter-Engadin area of the Swiss canton of Graubünden. His god-fearing parents, Thomas and Ursula Cattaneo, intended him for the ministry from the beginning. They taught him short prayers, verses from hymns, and religious sayings from an early age. Beginning at age 7, he went to the village school and learned to read, write, sing, and acquaint himself with Hubner's biblical stories. Then his father died in 1755. Cattaneo's guardian, the pastor Sebastian Sekka, assumed responsibility for his education. Later in life, Cattaneo often fondly recalled the blessing he found in preparing for his first communion. After 2 years of education with his erudite uncle Peter von Porta, Cattaneo left for the university in Zürich to pursue divinity studies. While boarding there with a physician, he found opportunities to acquire medical training, especially in surgery. In 1766, Cattaneo completed his studies with the highest honors and became pastor in Fläsch, where he was blessed to work for 4 years. After a subsequent 1-year service in Tschuders, he was called to be pastor in St. Anthony, where he remained for 13 years. In the meantime, he had married in 1770. Then, while on a trip to Chur in 1784, he was unexpectedly called to serve as pastor in Norka. He accepted the post and departed for the Volga on the 5th of May in the same year with his wife and 6 children. He arrived on the 3rd of August, 1784.* He served in Norka with an occasional hiatus until the 15th of March, 1828, and then died peacefully in his sleep on the morning of January 16, 1831.

During his first year in Russia Cattaneo wrote a small book well worth reading: "Eine Reise durch Deutschland und Rußland, seinen Freunden beschrieben von Johann Baptista Cattaneo aus Bünden, gegenwärtigem Pfarrer einer reformierten deutschen Colonie zu Norka in der Saratowischen Statthalterschaft an der Wolga in der russischen Tatarey in Asien. Chur 1787". In this work, the author describes the impressions he gathered in the various lands he traversed on the journey. He presents especially valuable material about the conditions in Russia at that time. A postscript offers a cultural description of the colonies on the Volga. This small book has been out of print for a long time and is only available at a handful of specialty bookshops. P. S.

II

Now, we should let Cattaneo speak for himself. Unfortunately, the beginning of his memoirs has been lost, so his accounts begin with the numerous trips he was obliged to undertake to the widespread Reformed communities. --

Night fell during one of my trips to Pobochnaya, and I unexpectedly stumbled across 10 to 12 unsavory characters -- Russians -- standing near some saddled horses. I had often been told that the woods near the Moscow highway harbored bandit gangs, and I did not doubt these wood folk were one of those. It was too late to make an escape because they had already noticed us; to approach them seemed a risky proposition. Nonetheless, I decided for the latter, strapped on my saber, equipped myself with a pair of loaded pistols, and made a stouthearted approach to their fire with my waggoneer following along. There was embarrassment on both sides. We at the prospect of this sizable little group, and they because they feared us to be officials of the Inquisition on the hunt for heretics, reinforced by a sizable contingent just down the road. Even though I did not attempt to dissemble and I openly answered their inquiries into the nature of our journey, they remained uncertain. I smoked my pipe peacefully in the back of my wagon and awaited the morning. But when it started to dawn, the others beat a hasty departure without molesting us. -- This occurred in the summer of 1788, and no one has heard from the bandits since.

Fellowship with the more remotely situated Germans I served was all the more pleasant since it happened infrequently. I found many opportunities to serve both the body and the soul of my fellow man. Although I often experienced adversity on those journeys, the joys of my service caused me to forget the difficulties, and I never feared to undertake future trips.

In 1791, during the winter, my wagoner and I lost our way on the other side of the Volga in the trackless steppes. Night fell, and we had to camp in the snow as best we could. In the morning, we found our way again and arrived at the next colony after a detour of about 30 versts. -- In the winter of 1816, we had to spend another night in the field during a heavy blizzard. I was in the colony of Splauwnucha (Huck), located about 10 versts from Norka, and departed from there in the afternoon in a heavy snowstorm. The weather steadily deteriorated, becoming especially dangerous for us because the wind drove the snow into our faces. After a long and arduous journey, I thought we had reached the outskirts of Norka. But once again, we lost our way, although we had already been underway for hours. In fact, we could no longer make any progress because the cold and the icy surface caused our horse to become unhitched; our wagoner could no longer re-hitch the horse again and again. Also, the horse was exhausted. We set up camp as night had long since fallen, and we found ourselves in unknown territory. I settled down in the snow, but the wagoner declared he could not hold out here; he had become overheated from repeatedly hitching the horse, and now he was freezing in his sweaty clothes. He set out again and fortunately found Norka. Then, people came out from the colony to search for me and brought me home at about 1:00 in the morning. -- In 1790, I was on the way to Splawnucha (Huck) across the Mühlen-See lake--the usual route between the two colonies in winter. But I broke through the ice and was thrown in. The necessities, my bedding, and my furs helped me to stay afloat and swim to shore. The wagoner safely stationed on the opposite bank with his sleigh watched all this frozen with horror while I froze from the cold. We eventually reached the colony about 2 versts further on, where I recovered without any ill effects.

In the spring of 1798, after the water had receded some, I was dragged into the water at the same location in half of a carriage--we had lost the rear axle and wheels in the descent of the bank. But the horse pulled the floating front half onto the other shore, where the nail broke that joined the rest of the wagon to the front. And so good fortune once again allowed me to sit high and dry after another adventure. I had to view it as a miracle of divine providence, as in so many other perils, to escape unscathed. To God be all praise and thanks!

In 1805, I took my son Lukas by post coach to the Imperial University in Dorpat, Livonia, about 2,000 versts from here. We had many good experiences in Moskow, St. Petersburg, and Dorpat. Our educational plans received especially generous support from His Imperial Majesty in St. Petersburg, and my son was graciously awarded a stipend of 1,200 rubles for his 3-year course of study. It was more than suitable that I should demonstrate my appreciation for this generosity by continuing my work of inoculating the population of every German village on the Volga against smallpox, a task I had already begun at the imperial request. After I had inoculated 8,000 children, His Majesty most graciously awarded me a gilded tobacco canister and, later, the cross of the Order of St. Vladimir to wear on my breast. My aforementioned son Lukas took his exams in St. Petersburg in 1808 after finishing his studies, was ordained to the ministry, and in accordance with my wishes, was assigned as my assistant. In the spring of 1809, he was called by official decree to serve as a preacher in the evangelical congregations in Astrakhan. After 2 years there, he returned to me with his wife and child, where he lived with me at my expense as an unpaid assistant until 1817. In that year, I appealed to the judicial council to be relieved of the duties that had become too burdensome for me. My request was granted, and my son was installed as my successor.

For 33 years, I have served this parish and have been an active pastor for 51 years. Now, I devote myself entirely at my convenience to spiritual duties since my 73 years remind me emphatically that my strength is diminishing. I continue my medical practice daily as there is always a need.

III

The Lord has also richly blessed me in this work. With humble thanks, I give testament: Lord, You are the Master; we are only poor tools in Your Hand. Among the many operations I performed up to 1819, I've noted down 16 amputations of arms, legs, fingers, etc., from which all recovered happily. I have treated 27 cases of cancer of the mouth, face, neck, and breast, which were operated on, and all were well-healed. Many who suffered from dropsy and sought timely help were restored to health. Other growths on various parts of the body, as well as many internal and external wounds and infirmities, were frequently cured. In my medical practice, I have always sought to employ the simplest medications and means to save myself and the patient's costs, for the simplest methods often lead to better recovery than do the expensive, more elaborately compounded medications.

I would like to relate several extraordinary cures because of their unusual nature.

The headman in Splawnucha (Huck) notified me about a colonist in his village who was so melancholy that he constantly talked of suicide and didn't do any work at all. Hence, the community had heeded an official decree for the past several years to feed him and his family. I visited the supposed invalid to hear his confession and tried to help him. But the man found his situation all too agreeable and showed no improvement. Finally, I had my fill, as had the entire village for some time already. I recruited four stalwart, honorable men from the village and went with them to visit the man. After discussing strategy with my four helpers beforehand, I proceeded to tell the man in no uncertain terms that he had sinned long enough by threatening for years to commit suicide and that the entire community considered him to be a suicide already. So it was high time he carried through with his threats; he had already burdened his fellow colonists long enough. We had come to be witnesses. I was ready to report back on his successful suicide, and he should get on with it and complete the devilish deed on the spot. With some difficulty, we got the well-fed fellow into his clothes. But before we finished, he began to haggle and bargain. First, he requested that we throw him in the water. This we immediately rejected as we desired no part of the sinful act of suicide. Finally, he asked for patience and promised to commit suicide by his own hand. We consented. But then, after more discussion, we all reached an agreement: he promised from that hour hence to return to his work and never threaten suicide again. He kept his word and has lived for some years since an orderly, respectable life, and worked to support himself and his family.

A colonist in Warenburg came to me and lamented the miserable condition of his 30-year-old daughter. Because of her delicate physical nature, she was spared from working in the fields. But since she had a good religious education and aptitude, she began giving religious instruction to children in addition to her normal feminine pursuits. In other respects, she led a quiet, decent life. Recently, she had begun to develop the peculiar and regrettable habit of mixing together the most sacred and profane behavior. She sang and prayed, laughed and danced, and bestowed the gentlest and most sentimental caresses on male passers-by. Amidst all this craziness, she acted as if this were the most normal thing in the world. And so I consented for her to be brought to our home in Norka, where she wreaked havoc day and night for several weeks. No medicines had any effect. Then, during one night--it was between Saturday and Sunday--she took everything that was not nailed down in the house and put it on display on the graves in the nearby cemetery. This was the last straw. I threatened to give her a good thrashing the next time she pulled such a stunt. But she behaved cute, as she did after every misdeed like this, and was convinced I would not carry through on my promise. The following night, her insane, self-supposed religious behavior was more deranged than ever. I kept my word and gave her a sound beating on the spot. She crept off--and was cured. Never again did she behave indecently or cantankerously. From that day, she led a quiet, upright, exemplary life.

Once, the Norka villager B. brought me his unmarried daughter, who was of age but insane. I found it necessary to open a vein in her foot to bleed her. The moment she saw blood, she began incessantly to scream at the top of her lungs to have the foot bandaged. When she was ignored, she exclaimed she was dying. Immediately, she fell down and screamed: I am dead, I am dead. Then she began to play the corpse. Her father suffered terrible fits of anxiety, but I reassured him and demanded we begin on the spot to prepare for the burial. I asked a man who was present to have a grave prepared, arrange for pallbearers, etc. The dead woman heard all this and not only resurrected but jumped up and hurried out the door and across the yard with the unbandaged foot. Her father had to exert himself considerably to catch up with her. She was cured, married later on in Norka, and never again showed a trace of mental illness.

Now, it seems probable I'll reach the end of my earthly journey before long--a journey filled with sin but redeemed by Christ. And so it is with humble and heartfelt thanks to my beloved Lord that I exclaim: You have shown me more patience, grace, and mercy than I can comprehend! I am of ashes and earth; what value am I? Nothing in me is of value other than what was accomplished by the blood of Jesus. He has loved me so! Oh God, what a gift of love and mercy I have in His death! How do I thank Him now? What can I do for Him? Oh, if only every drop of my blood could be hallowed to honor Him! -- Norka, March 27, 1819.

Today is April 30, 1826, and I am still healthy. Since I am well and, by the grace of the Lord, still strong and active, it seems fitting that I should append the following.

In 1821, in the middle of March, the recently established Evangelical Synod in Saratov undertook an extensive reorganization of the various preachers and parishes. This resulted in my son, Lukas, going as pastor to the Talowka (Beideck) parish and the parish in Norka unanimously asking me, this old preacher, not to abandon them as long as I should still live. I decided to consent to their wishes. Since then, I have been their sole preacher and spiritual shepherd. And by the grace of the Lord, I have remained healthy and able to fulfill all pastoral duties promptly and faithfully! In July 1825, I visited the Brethren in Sarepta and enjoyed celebrating my 80th birthday with my children. I then returned in good health and reinvigorated to my beloved parish, where I stand ready to live or die according to the will and mercy of the Lord. May He grant me the consolation of my faith: I know in whom I believe, and He will delay my burial until the appointed time.

Thus, this ends the memoirs of J. B. Cattaneo.

Source

The memoirs of Johann Baptist Cattaneo, one of the most notable pastors of the Reformed Church in Norka, were published in the 1923 edition of the Wolgadeutsche Monatshefte, Volume 2, pp. 23-5. The author introducing Cattaneo's own words is probably the Volga German, Peter Sinner, who was editor of the Wolgadeutsche Monatshefte at that time. This work was translated by Robert Bradley and is posted here with his permission. Read more about Robert Bradley's interest in Rev. Cattaneo.

The original German version of the memoirs can be read here.

The original German version of the memoirs can be read here.

Last updated February 5, 2024