Jacob Klaus

by Lois Klaus (Jacob's daughter)

Jacob was born to Jacob and Louisa Klaus on September 29, 1893, in Norka, Saratov Province, Russia. He was the youngest of eight children (five boys and three girls). Only three of the boys came to the United States.

He never said much of his youth. Russia was something he didn’t like to talk about. Cousin Lena Richard mentioned a number of times that Jacob baby sat her. At one time he helped her make a nest out in the summer kitchen for the Easter bunny. School was taught by the church pastor. As I understood it, he only went through about eight grades. However, when I was in high school and sweating over several algebra problems, one night, he offered to help me (the only time that I can remember), and much to my surprise he worked the problems, although differently than we would, but he came up with the right answers. I was really impressed.

At the age of 17 Jacob went into the army. He was in the Tsar’s army, the White Army, and one other. There seem to have been a lot of changes of government about this time. When an army came to town, they stayed in the homes of the residents, and the people had to take care of the army, but the army slept in their homes. At the end of his army career, one day while they were getting their horses ready to leave in the morning, he discovered that he had left his Bible in the house where he had been staying. He went to retrieve it. On the way someone told him that he had better run as he would be killed. He did not know who this person was, but later believed it was his guardian angel. He took off and hid for about two years. All the other soldiers in his unit lost their lives. First, he ran to his sister’s house. However, they felt that was not a safe place. At one point he hid under a strawstack at the home of Mrs. Schultz, who used to live at Seaside. (She herself told me this.) She remembered taking food out to him. He also said that he would be forever grateful to an elderly Russian couple. The man made Jacob a pair of shoes from rubber tires.

Jacob did not like to talk about this part of his life, and we tried not to ask too many questions as it always made him cry. Later, at one point in Norka he had to dig his own grave. He begged his captors to be able to go home and say goodbye to his mother. This was granted. However, when he got home, his mother hid him in the attic, and he was never found.

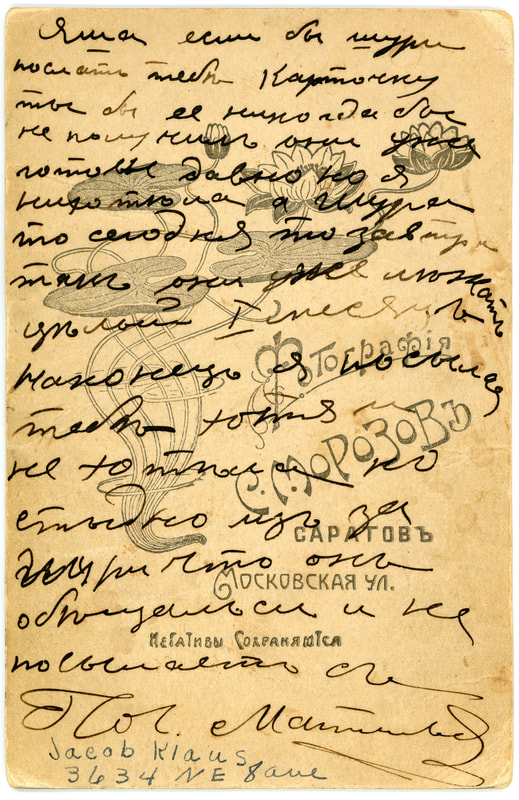

At some point in Jacob’s life he went to Saratov to learn tailoring. It was there he met David K. Schmidt. One time Mrs. John Pauli of Portland told me that her father had taught Jacob tailoring. (After Jacob retired, he announced that he would now be the chief sewer on of buttons around the house. We just left it out for him, and when we came home in the evening, it was done.)

In 1921 and 1922 there was an awful famine which went through this area. There was no food to be found. Jacob said that one would go through the market, and there was nothing. If one did get something, it was hid inside his coat so no one would see it and it would be taken away. One thing they had to eat was kartoffel and klösse (potatoes and small dumplings). Later, Jacob would never allow that dish to be cooked in our home, and Mother honored his wishes. Many years later, we would always eat very well at our house. Jacob said that as long as we had it, we should eat because we didn’t know when we would not have food.

The latter part of 1923 Jacob and his mother left Russia to come to America to join Jacob’s brothers John and Peter Klaus, who were living in Portland. In 1960, another John Klaus, who was then living in Johnstown, Colorado, interviewed Jacob. He states that “He [Jacob] was scheduled to be killed by the communists. That night he and his mother prayed all night. In the morning the executioners passed his place. So he and his mother fled and made it to the U.S. with the aid of Peter and John in the U.S.”

In an application for life insurance which Jacob filled out in 1926, he lists having a severe case of typhus fever for two months in 1920 for which he was hospitalized. I do not recall him ever mentioning this. This same application lists that his father passed away at about 65 years of ago. This same application also says that in 1926 Jacob had been a tailor for 15 years.

After coming to the U.S., Jacob went to Ritzville, Washington, to visit his friend D. K. Schmidt. While in Ritzville, he met Leah Matilda Thiel, who lived on the same block as the Schmidts. They were married in 1930, and Leah moved to Portland. Lois Kathryn was born in 1934 and Ruth Gayle in 1938. Jacob’s mother, Louisa, who lived with Jacob and Leah, died in Portland in 1937.

The 1930s were tough times, and tailoring certainly didn’t bring in much money. At one point Jacob was digging ditches on 15th Avenue in order to make money. Later, he went into the garbage business with an Italian man and later had his own garbage business. His brother Peter also was in the garbage business along with many of the German Russian immigrants to Portland. This was hard work, but Jacob persevered. He always encouraged young fellows to go to college and get a good job so they wouldn’t have to work so hard.

Because of the experiences Jacob had had in the early part of his life, he always read from the Bible and prayed each morning. He never left the house without doing this. Looking back, this is probably what kept him going.

Jacob was very active in the prayer meeting at Ebenezer Congregational Church which was held three times a week—Wednesday evening, Saturday evening, and Sunday afternoon. About four times a year there was a church conference. We always had company those weekends, and Ruth and I spent almost the whole time doing dishes. Jacob would stand at the back of the church and invite anyone who didn’t have a place to go. We always had a table full. Also, we often had house guests, which meant that I had to move from my bed. We had a rollaway in the basement.

When Jacob retired, he decided that he would attend a prayer meeting in a black church a couple of blocks from where we lived. When I came home from work, I asked him about his experience. He kind of shook his head. I said to him, “I bet you forgot your tambourine.” He laughed, and that was the end of attending the black church. Jacob made friends with the black people in the neighborhood, some attended his funeral, and a group of black ladies called on Mother and brought a coffee pot and crackers which were to be used until after the funeral.

In 1966 Jacob had a stroke on a Sunday morning. I was in church playing the organ, and Ruth had gone home from Sunday School to pick up Jacob and Leah. However, they never came to church. I knew something was terribly wrong. After church I rushed home to see ambulance drivers bringing Jacob out of the front door of the house on a stretcher. The following Monday night we received a call in the middle of the night saying Jacob had passed away. He was never conscience after having had the stroke. This happened about three weeks before Ruth and Archie’s wedding. Ruth was told by both Dr. Sittner and Rev. Gyorog to go ahead with the wedding, but it wasn’t easy. Some of Ruth’s college friends had come to the wedding from Idaho and were wondering where Jacob was.

Two years after Jacob died, Leah sold the original house at 3634 N.E. 8th Avenue which Jacob had had built, and she and Lois moved to 111 N.E. 67th Avenue.

At the age of 17 Jacob went into the army. He was in the Tsar’s army, the White Army, and one other. There seem to have been a lot of changes of government about this time. When an army came to town, they stayed in the homes of the residents, and the people had to take care of the army, but the army slept in their homes. At the end of his army career, one day while they were getting their horses ready to leave in the morning, he discovered that he had left his Bible in the house where he had been staying. He went to retrieve it. On the way someone told him that he had better run as he would be killed. He did not know who this person was, but later believed it was his guardian angel. He took off and hid for about two years. All the other soldiers in his unit lost their lives. First, he ran to his sister’s house. However, they felt that was not a safe place. At one point he hid under a strawstack at the home of Mrs. Schultz, who used to live at Seaside. (She herself told me this.) She remembered taking food out to him. He also said that he would be forever grateful to an elderly Russian couple. The man made Jacob a pair of shoes from rubber tires.

Jacob did not like to talk about this part of his life, and we tried not to ask too many questions as it always made him cry. Later, at one point in Norka he had to dig his own grave. He begged his captors to be able to go home and say goodbye to his mother. This was granted. However, when he got home, his mother hid him in the attic, and he was never found.

At some point in Jacob’s life he went to Saratov to learn tailoring. It was there he met David K. Schmidt. One time Mrs. John Pauli of Portland told me that her father had taught Jacob tailoring. (After Jacob retired, he announced that he would now be the chief sewer on of buttons around the house. We just left it out for him, and when we came home in the evening, it was done.)

In 1921 and 1922 there was an awful famine which went through this area. There was no food to be found. Jacob said that one would go through the market, and there was nothing. If one did get something, it was hid inside his coat so no one would see it and it would be taken away. One thing they had to eat was kartoffel and klösse (potatoes and small dumplings). Later, Jacob would never allow that dish to be cooked in our home, and Mother honored his wishes. Many years later, we would always eat very well at our house. Jacob said that as long as we had it, we should eat because we didn’t know when we would not have food.

The latter part of 1923 Jacob and his mother left Russia to come to America to join Jacob’s brothers John and Peter Klaus, who were living in Portland. In 1960, another John Klaus, who was then living in Johnstown, Colorado, interviewed Jacob. He states that “He [Jacob] was scheduled to be killed by the communists. That night he and his mother prayed all night. In the morning the executioners passed his place. So he and his mother fled and made it to the U.S. with the aid of Peter and John in the U.S.”

In an application for life insurance which Jacob filled out in 1926, he lists having a severe case of typhus fever for two months in 1920 for which he was hospitalized. I do not recall him ever mentioning this. This same application lists that his father passed away at about 65 years of ago. This same application also says that in 1926 Jacob had been a tailor for 15 years.

After coming to the U.S., Jacob went to Ritzville, Washington, to visit his friend D. K. Schmidt. While in Ritzville, he met Leah Matilda Thiel, who lived on the same block as the Schmidts. They were married in 1930, and Leah moved to Portland. Lois Kathryn was born in 1934 and Ruth Gayle in 1938. Jacob’s mother, Louisa, who lived with Jacob and Leah, died in Portland in 1937.

The 1930s were tough times, and tailoring certainly didn’t bring in much money. At one point Jacob was digging ditches on 15th Avenue in order to make money. Later, he went into the garbage business with an Italian man and later had his own garbage business. His brother Peter also was in the garbage business along with many of the German Russian immigrants to Portland. This was hard work, but Jacob persevered. He always encouraged young fellows to go to college and get a good job so they wouldn’t have to work so hard.

Because of the experiences Jacob had had in the early part of his life, he always read from the Bible and prayed each morning. He never left the house without doing this. Looking back, this is probably what kept him going.

Jacob was very active in the prayer meeting at Ebenezer Congregational Church which was held three times a week—Wednesday evening, Saturday evening, and Sunday afternoon. About four times a year there was a church conference. We always had company those weekends, and Ruth and I spent almost the whole time doing dishes. Jacob would stand at the back of the church and invite anyone who didn’t have a place to go. We always had a table full. Also, we often had house guests, which meant that I had to move from my bed. We had a rollaway in the basement.

When Jacob retired, he decided that he would attend a prayer meeting in a black church a couple of blocks from where we lived. When I came home from work, I asked him about his experience. He kind of shook his head. I said to him, “I bet you forgot your tambourine.” He laughed, and that was the end of attending the black church. Jacob made friends with the black people in the neighborhood, some attended his funeral, and a group of black ladies called on Mother and brought a coffee pot and crackers which were to be used until after the funeral.

In 1966 Jacob had a stroke on a Sunday morning. I was in church playing the organ, and Ruth had gone home from Sunday School to pick up Jacob and Leah. However, they never came to church. I knew something was terribly wrong. After church I rushed home to see ambulance drivers bringing Jacob out of the front door of the house on a stretcher. The following Monday night we received a call in the middle of the night saying Jacob had passed away. He was never conscience after having had the stroke. This happened about three weeks before Ruth and Archie’s wedding. Ruth was told by both Dr. Sittner and Rev. Gyorog to go ahead with the wedding, but it wasn’t easy. Some of Ruth’s college friends had come to the wedding from Idaho and were wondering where Jacob was.

Two years after Jacob died, Leah sold the original house at 3634 N.E. 8th Avenue which Jacob had had built, and she and Lois moved to 111 N.E. 67th Avenue.

Note

Jacob's sister, Dorothea, married Heinrich (Henry) Krieger. Henry was the son of Nicolaus "Garte" Krieger. Henry, Dorothea and their family is shown in the 1928 film taken in Norka by Heinrich Wacker.

Source

Written by Lois Klaus, Portland, Oregon, February 20, 2002. Lois is the daughter of Jacob Klaus. Used with permission.

If you have additional information or questions about this family, please Contact Us.

If you have additional information or questions about this family, please Contact Us.

Last updated September 18, 2020.